Goodman Arts Centre is a fascinating place indeed.

The sprawling campus still looks very much like an old school, with low-rise slab blocks, stairs, few lifts and classroom-sized areas spaced equally apart on long corridors.

And the first thing, of course, that you notice, is the logo of the National Arts Council (NAC) — displayed quite prominently at both the main entrance (from a small road you would chiefly access by car) and its back gate, which faces the main road, a short stroll from Mountbatten MRT station.

That's where we found ourselves as we trundled through the maze of blocks — past dance studios, theatre rooms, workspaces with canvases displayed outside, choir and band rehearsal rooms. We cautiously skirted the air-conditioned offices of the NAC, and then found ourselves crossing an open space flanked partially with three exponentially-larger-than-life Javan mynah statues to a C-shaped slab block that was five storeys high.

And while one would expect to envision the imagery of the NAC's offices casting a bird's eye view over the hive of activities of all the art forms, companies and artists at Goodman Arts Centre, it turns out to be the other way round for Singaporean comic artist Sonny Liew.

Photo by Tan Guan Zhen

Photo by Tan Guan Zhen

His studio/office/workspace, as it stands, is at the top floor of the furthest-out block in the campus. Standing outside his door, which is spray-painted "THE SECRET ROBOT SPY FACTORY", one actually enjoys a comprehensive top-down view of the NAC block.

We had a bit of time to study a series of potted plants with signs like "CAUTION: Whomping Willow" and "Mandragora Officinarum (Mandrake)", remnants of a Harry Potter-themed party held at his studio not too long ago, before we spied a backpack-carrying Liew in a black tee, jeans and running shoes crossing the lawn downstairs.

And everything we read about him was true — he may be 42, but doesn't look a day older than 25, and cuts a lithe physique thanks to his regular running (he has at least nine pairs of running shoes parked just inside his studio door, alongside three pairs of flip-flops and at least one pair of socks).

It might be the fact that he does for work what most boys can only dream of — short of playing computer games competitively for a living — living the world of DC, Marvel, reading and drawing, day in, day out; essentially, getting to be a boy every day for work, and for life.

A cordial love-hate relationship

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

The irony of his studio location does not escape the very meek-looking Liew, who read philosophy at Cambridge University before going to the Rhode Island School of Design as one of his first official steps toward kicking off his comic-drawing career.

He tells us, with a chuckle, about the day he returned to Goodman from a whirlwind America trip that saw him sweep a historic half of the record-setting six Eisner awards he was nominated for, when he happened to run into none other than NAC Deputy CEO Paul Tan:

"He was parking his car, I was walking past him... He actually did say 'hello, oh yeah congratulations', and he actually made it a point to say the name of the book, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. But you know, he was off the record, I suppose — a conversation in a car park."

Despite the now-quite-widely-known move to pull a $8,000 funding grant that rocketed Charlie Chan to local, and then international fame, as well as the terse congratulatory message that wouldn't even mention Liew's graphic novel title, the fact is Liew and the NAC do have a reasonably close working relationship.

His name comes up in at least seven mentions from a cursory search of the NAC's website:

Screenshot from NAC website

Screenshot from NAC website

Liew is also the recipient of the NAC Young Artist Award in 2010, and the arts council has indeed gone on to involve him in various initiatives and projects as a mentor and an artist.

That didn't end with their funding withdrawal, which caused Liew and his publisher, Epigram Books, inconvenience in having to paste over their logo in his first run of printed copies, but also saw him go on to massive heights.

And so he says he sees this as a double-edged sword:

"On one hand you have to raise the profile, hard sell the books; on the other hand, I'm not sure (if) it would prevent some people from reading it, because as much as some people are excited about the fact that there's some notoriety attached, there are other people I'm sure who also see that as being a negative thing, 'oh this is anti-government'."

Making the NAC clam up

More importantly, though, he worries that this entire episode has made the government body retreat further into its shell instead of stepping out to engage artists like him in conversation — especially about the tricky issue of "sensitive content".

"I hoped the book would be a sort of a way for the NAC to address some of the issues that we’ve raised, but I think it’s actually pushed things backwards a little bit because their reaction has actually been to, kind of clam up and not want to discuss the issues as much.

Even the publishers are feeling sort of a backlash in that they are much more... (they tend to) scrutinise the grant applications a lot more now... because they don’t want to repeat the same mistake, even though Jeremy Tiang kind of happened again, but in general, they are more careful."

That being said, Liew still holds out hope that perhaps sometime later on, this conversation, between Singapore's regulators and content creators like him, will someday be opened up properly. Whether the public is involved in that discussion is another story, but past experience showed him the NAC was reasonable, for instance, with technicalities about grant conditions for comic artists that they eventually managed to get the council to modify.

[related_story]

Imagining alternative universes

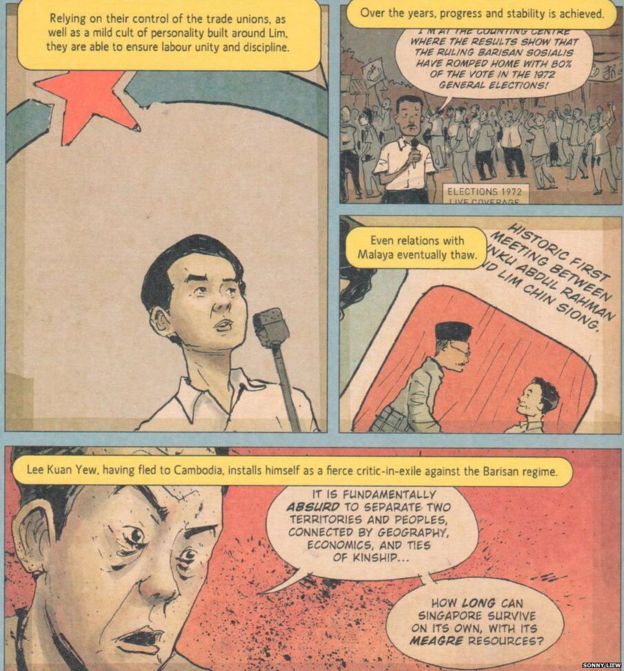

Page from The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew

Page from The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew

Now it was never actually articulated what exactly it was in The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye that resulted in the NAC withdrawing its funding, apart from the official line of there being "sensitive content", and that "the retelling of Singapore’s history in the work potentially undermines the authority or legitimacy of the government and its public institutions".

One possibility is Liew's imagining of an alternate universe where Lim Chin Siong's Barisan Sosialis was not clamped down upon through 1963's Operation Coldstore, took power and was able to still bring Singapore to where it is today.

"It's just one possible (scenario)... you can say that okay, what would they have done, or what could they have done? And you could have argued that given the constraints at that time, maybe they were forced to do similar things to what the PAP did. But that's just a maybe, right? They could also have done very different things."

The idea to do that chiefly came from Philip K. Dick's book The Man in the High Castle, although Liew also says there are, of course, many alternative timeline stories that exist.

"I mean, the whole point at the end of it — when it kind of collapses on itself — I think that was for me at least, to indicate that reality is what it is, and any speculation is just... it can be fun to kind of imagine what the possibilities or constraints were.

But we can only really have the present, and reality is what we have, la. So it's just more a theoretical exercise rather than saying what could have really happened, because we don't really know what could happen in these alternative universes."

A "semi-active dissident"

Has this whole thing made Liew a dissident? No, he says, for to his mind, one should not be too antagonistic because you would not get a positively-motivated response to the point you wish to make.

Liew describes himself as "centre-left", rather than far left, and stresses he isn't an activist — his efforts, even when he throws his weight or voice behind certain causes, remain at the fringes of lobbying activity.

Save for someone tabling a billion-dollar merchandising deal, which he would pretty much sign right away, he's also cautious about accepting offers that have come his way thus far. Liew has only had items made in collaboration with Kinokuniya, which for him was a huge supporter of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, and has turned down offers to make T-shirts and boiled Charlie Chan rock candy.

"There's a part of me that still remembers Calvin & Hobbes, and Bill Watterson refusing to merchandise his characters, and there's something to that, I would say."

A 5-year-old Singaporean

See any resemblance? Photo by Tan Guan Zhen

See any resemblance? Photo by Tan Guan Zhen

Liew was born a Malaysian, but he's been living here since he was five, and became a Singapore citizen five years ago. He did not have to serve NS, but he admits he did feel a bit of FOMO (although we had to explain to him what that was — fear of missing out) when his JC friends went through it.

In fact, he thinks that if he were younger when he obtained citizenship, it's possible he would have enlisted — if perhaps just so he would understand and be able to contribute to discussions his friends had throughout those two years.

"I remember at the time I was like, 18. I felt left out, and thought about enlisting, at some point... it was just something I thought about. But my friends were like, 'don't be stupid!', and as much as they talked about it all the time, they told me, 'if I were you, I wouldn't do it, why would I?!' So, yeah."

We wondered, then, if his Malaysian relatives and friends might have asked him why he did this work for Singapore, instead of doing the equivalent for Malaysia.

"Some friends who were comic artists, when the book came out, they asked me, 'are you going to do something like this for Malaysia?', and I told them, no, you guys should be doing it yourselves, because you're *in* Malaysia — and then, some of them would say, you know, you can get into real trouble here."

But he doesn't think his friends are afraid of incarceration or persecution for doing something like what he did with Charlie Chan — he thinks it's more that they simply don't have the inclination to do so.

A ton of work for not much money

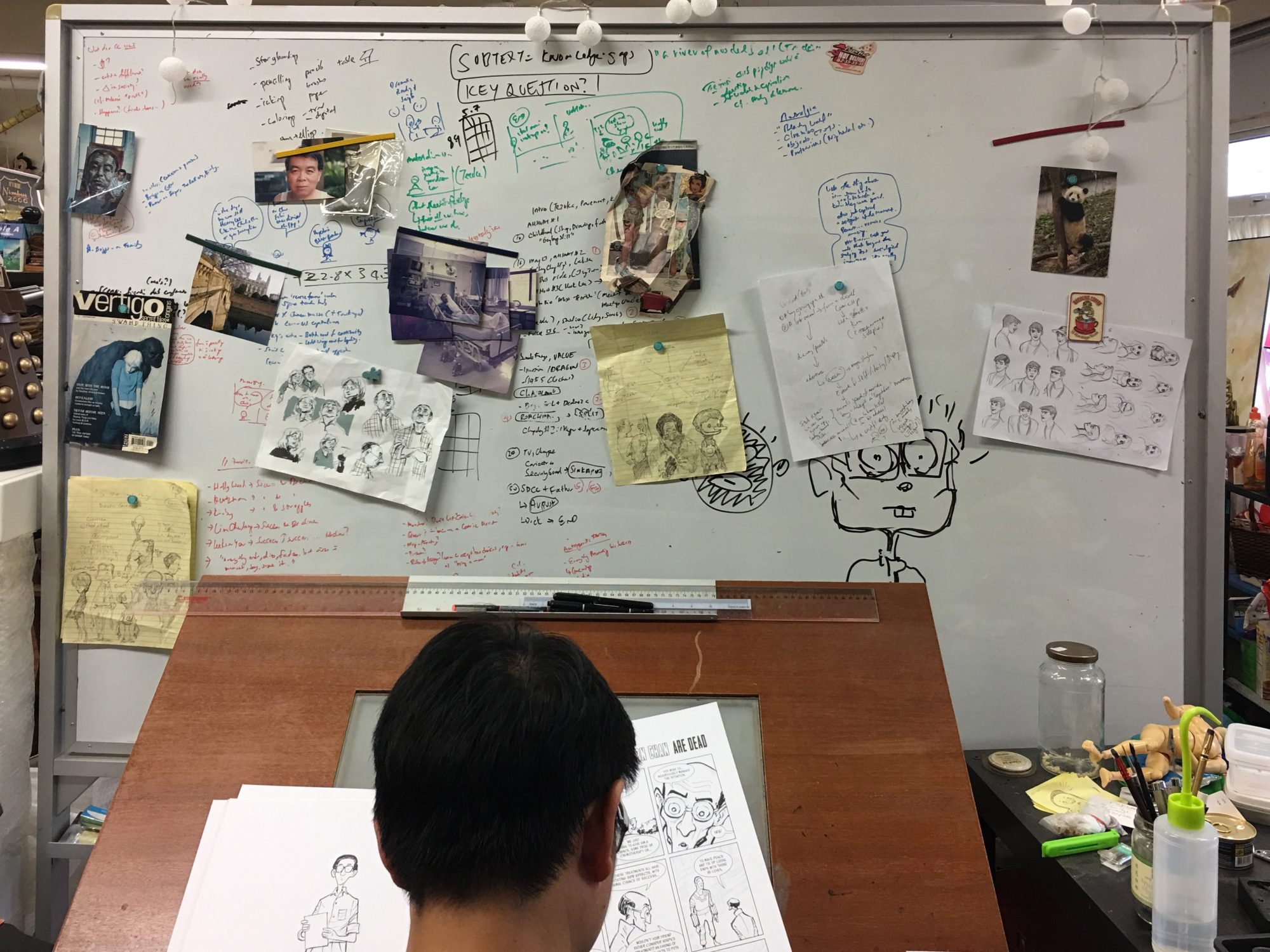

Charlie Chan was really a lot of work, though — over the span of between two and three years, Liew did nearly the whole process of production: thumbnailing (storyboarding), pencilling (drawing everything in pencil), inking (going over it with pen), colouring and lettering (putting the words in).

He had help with adding flat colours to some of his book (he would later have to add shading on his own), and he acknowledges his editor for doing "a lot of the heavy lifting" on the project. Let it be known, however, that several of the images that looked like paintings were in fact real oil paintings — now hanging or propped up around his studio — that he spent a full day or two doing, just so he could incorporate photographs of them into his book.

And on the whole, Liew was investing all that time and energy into it with no idea if anyone would actually read or buy it — it was entirely possible, at the time, that it would tank.

In September 2016, Liew transparently published his earnings from Charlie Chan Hock Chye on Facebook to highlight the challenges with working on independent projects like this. Here's the main bit:

"CCHC took about 2 years to complete – the research and bulk of the writing and drawing took about 18 months, followed by another 6 months or so of editing and polishing. In between I did a few other things, such as the book on Georgette Chen, and a couple of illustration projects here and there.

Leaving aside the inbetweeners, here’s the breakdown of the moolah from CCHC so far (note: comics tend to receive lower advances in the book world as they’re more of a niche market than, say, literary fiction):

Epigram Books Advance: SGD$9000

Epigram Royalties (2015): SGD$5,333.23

Pantheon Books Advance: USD$25000 = approx SGD$33,750 (1.35 exchange rate)

Less Agent's Fee and Epigram Cut= SGD$20,000

French Advance: 15,000 Euros = approx SGD$23,000 (1.5 exchange rate)

Less Agent's Fee and Epigram Cut= SGD$13,200

Italian: USD$3617 = approx SGD$4900

Less Agent's Fee and Epigram Cut=SGD $2,800

SG Lit Prize= SGD$10,000

Total= approx SGD$60,000

That translates into, over 24 months, about 2.5k/month."

And that was money he had to wait quite a while before getting, all in — even for such a successful book, which truly lends credence to the cliché of a struggling artist.

In fairness, that was in September 2016, and the book has gone on to a number of additional print runs, so there's likely to be more revenue from it. But on the whole, it was a mighty big risk Liew took, going all-in on Charlie Chan Hock Chye.

Still doing superbly

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Now, don't get us wrong — Liew is doing remarkably well for himself. Even before his breakout success with The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, he had previously done work with both American giants DC and Marvel.

He's in talks for a huge project he himself is excited about, and which we were very excited to hear about as well, but we regrettably can't share its details till it's confirmed — only that it's so huge that even the non-geeks in the room like us knew it.

And there is also his next big book on capitalism that he's working on, which we're likely to see the fruits of in the coming three years or so.

Photo stealthily taken by Jeanette Tan

Photo stealthily taken by Jeanette Tan

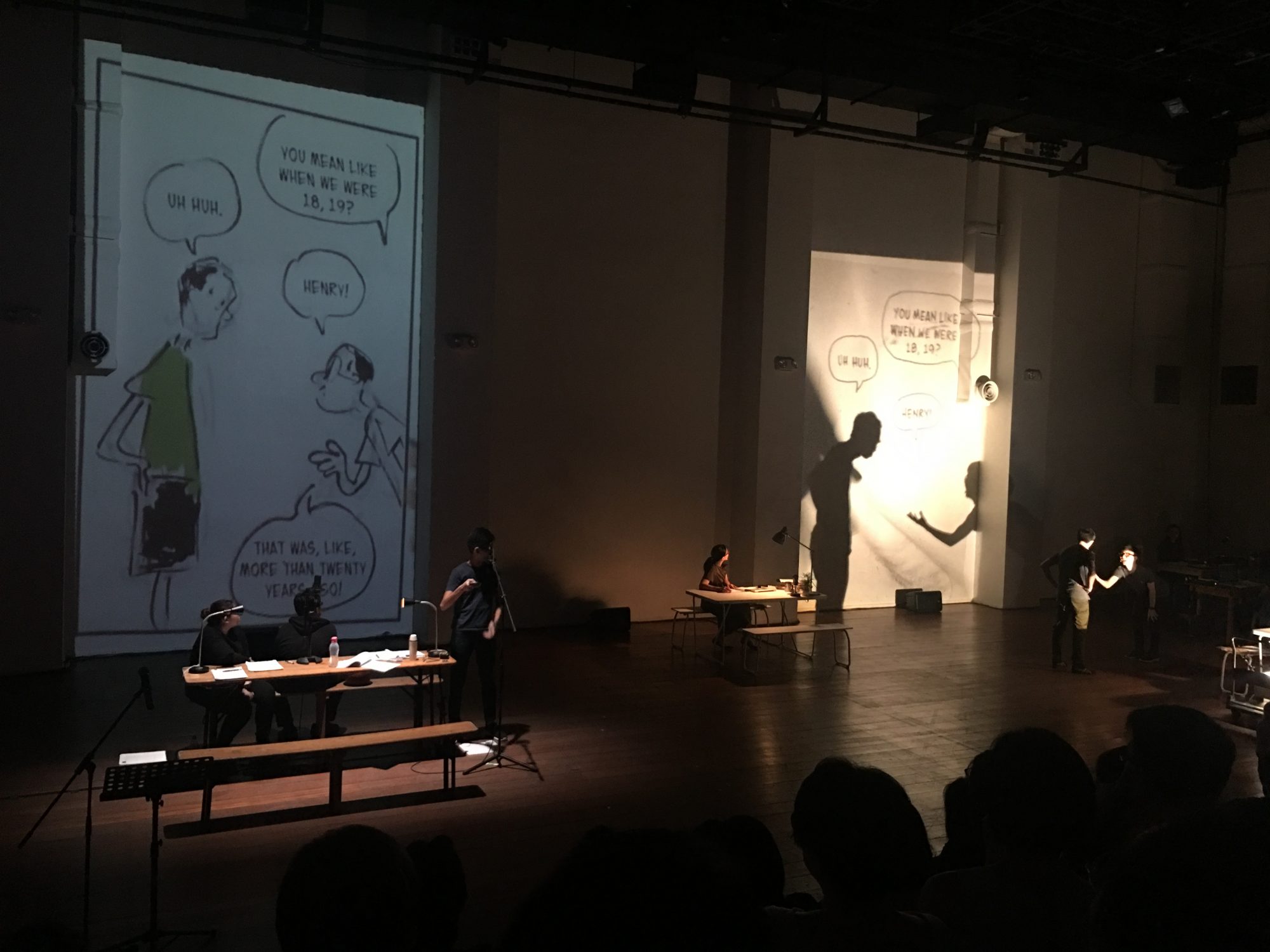

We also haven't talked about his wildly successful first venture into theatre — "Becoming Graphic", a complex, multi-layered masterpiece using various forms of media directed by Edith Podesta and which featured Liew sitting on stage and drawing live.

The play was commissioned and ran six shows exclusively at the Singapore International Festival of Arts, over four days — all were sold out.

But ultimately it's true — this life is a tough one, and not every Singaporean comic artist (or indeed, any Singaporean artist) is going to find a runaway success like Liew did with The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye.

Is there anything we can do as a society to support the arts better? To get an idea of the answer, it might perhaps be worth returning to Goodman Arts Centre's campus, where the only places to eat there are too expensive for the resident artists, and the deceptive proximity their workspaces have with the NAC's offices eventually betrays a cold distance and communication breakdown that continues to exist between them.

As we walked out of Liew's office, we would belatedly notice a tall concrete human-shaped statue, hand stretched forward as if to offer an allowance, looming over a host of smaller sculptures in the yard below — perhaps an all-too-apt reminder of the mindset and system that's bogging down our artists of today.

Top photo by Tan Guan Zhen

Here are some totally unrelated but equally interesting stories:

Enhanced Internships — The next big thing? Two poly grads share their experience

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.