Bukit Ho Swee lives on in many Singaporeans' consciousness as the village that got razed to the ground in a massive inferno.

The Bukit Ho Swee fire on May 25, 1961, eventually killed four people, left 16,000 kampung dwellers homeless, and caused an estimated S$2 million in damages -- a huge sum at that time.

But the kampung's fiery demise serves as the decisive moment Singapore made the transition to high-rise public housing.

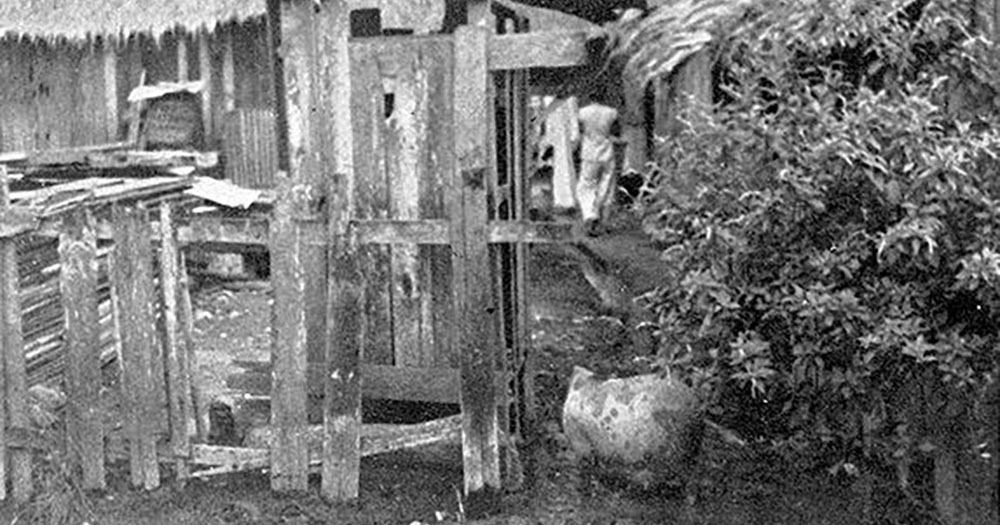

Stripping away any romantic notions of kampung living, Bukit Ho Swee was typical of the hazardous conditions that the low-income population of Singapore lived in during those times.

A slum of graves and no sanitation

Bukit Ho Swee was home to low-income Chinese families.

Assistant Professor Loh Kah Seng from the Institute of East Asian Studies at Sogang University wrote in his book, Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore:

"Amenities were at a premium. Rubbish, clogged drains and pools of stagnant water were part of the kampung landscape, while pedestrian paths became mud tracks after heavy rains."

What's more, as Bukit Ho Swee did not have any sewers, there was only the "typical kampung toilet", which consisted of either a wooden shed built over a drain or containing a pail that was shared by multiple families.

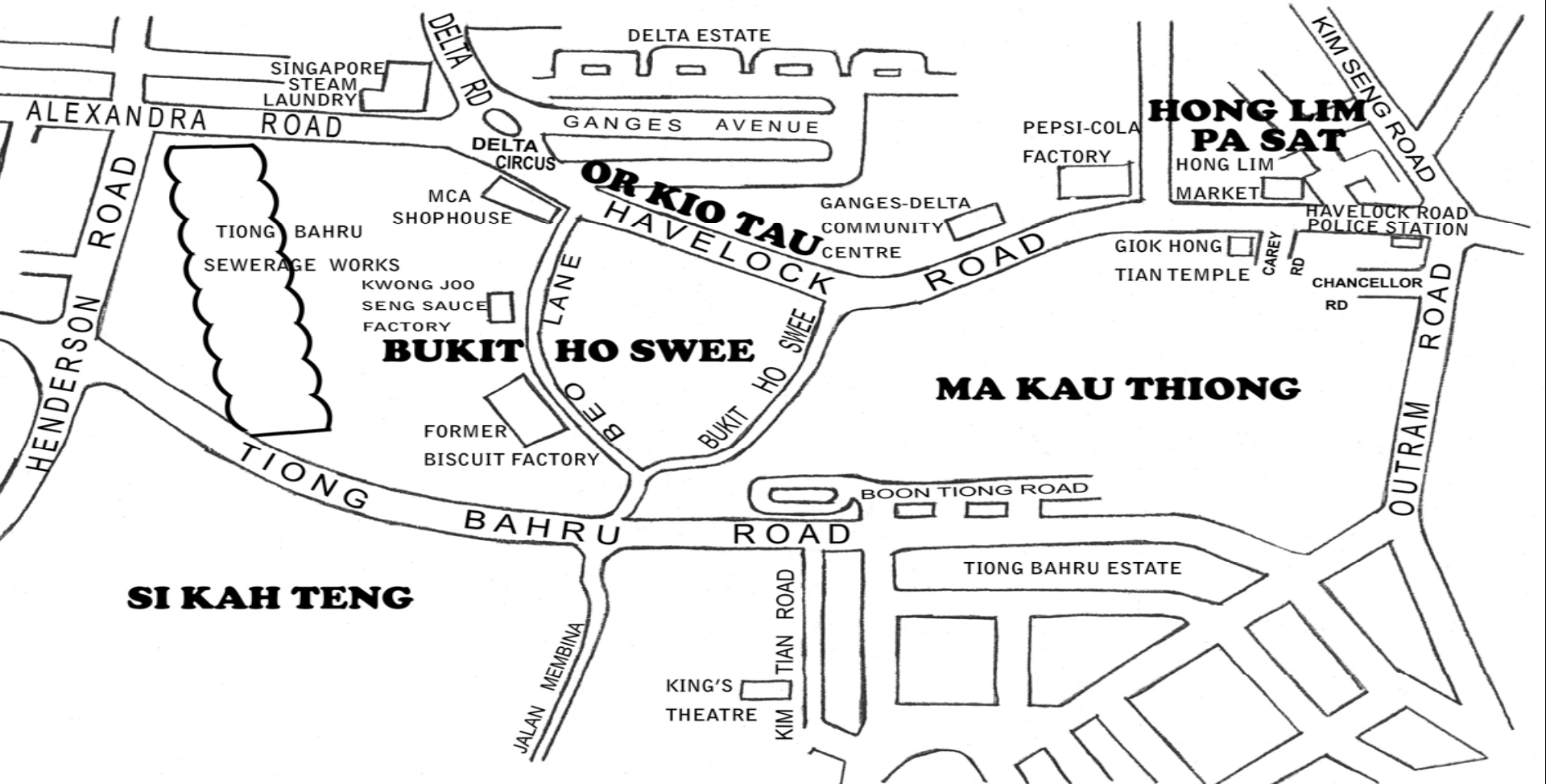

To top it off, part of the kampung was a former Hokkien cemetery -- specifically, the area bounded by Beo Lane and Bukit Ho Swee (Road), according to Loh.

Bukit Ho Swee also bordered a second cemetery called Ma Kau Tiong.

Source: Street Directory and Guide to Singapore (Singapore: Survey Department, 1957)

Source: Street Directory and Guide to Singapore (Singapore: Survey Department, 1957)

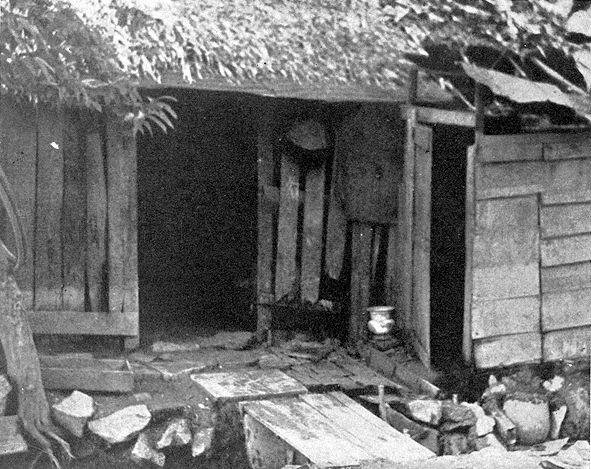

Given the haphazard standards of construction at the time of the 1950s, this meant that the still-living inhabitants ended up in constant close contact with the inhabitants of the grave.

Death was a daily feature

Such close proximity significantly shaped the attitudes of the kampung-dwellers towards the dead, resulting in the emergence of a rather blasé perspective.

Lee Soo Seong, a former Bukit Ho Swee resident featured in Loh's book, recounted: "Living people and dead people were neighbours. We didn't feel afraid."

After all, his own kitchen had a grave beneath it.

Another featured former resident, Tay Bok Chiu, highlighted how "builders didn't care, they just levelled the gravestone and paved cement over it and built the house to make money".

Ong Chye Ho, another resident whose home was also built over a grave, said: "What was there to be afraid of? They are dead."

And these weren't the only reminders.

Loh reveals more details such as the use of "coffin boards... to bridge small canals or build pigsties", and the neighbouring cemetery Ma Kau Tiong serving as a playground for children.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Source: National Archives of Singapore

According to another former resident, Chua Beng Huat, play in the cemetery as children would consist of "... running around and digging into holes looking for bones".

Lee also recalled, "sitting on straw mats placed over the dead and [listening] as the adults told stories".

Even so, the new attitude towards death did not detract from the significance of the Hungry Ghost Festival.

Rather, it only added to its significance.

A moment of grandeur, prestige and good business

In the words of Chua:

"The Hungry Ghost Festival was very big. There was a platform built on the entire road, and it would be covered with food. Huge amounts of paper money were burned, and the fires burned all day... We often took up a whole section of the podium because my mother was a big believer. At the end of the day, we kids ran about giving out food to neighbours and relatives."

Loh also pointed out how it was an important moment for the "wealthier residents... [and] management boards of local temples" to showcase their prestige.

As the festival's organisers, such an event helped to "reinforce their social status as the kampung's elite", as the head of tontines or hweis.

[related_story]

These were an "informal system of rotating credit" that provided help "for the low-income group unable to utilise bank credit, for which securities or guarantors were required".

The scale of the festival was also a good business opportunity for hawkers as it meant an upsurge in the demand for food.

But above all, the festival contributed strongly to reinforcing communal ties in the kampung and forging "a strong sense of community that was characteristic of rural life".

Top image from National Archives of Singapore

Content that keeps Mothership.sg going

??

Stand a chance to win Lomo cameras from Singapore Art Museum at Imaginarium and APB Foundation Signature Art Prize Exhibition.

? ?

Get a boost for your instagram street cred this 7th Month

?

Travel Malaysia like a boss with these tips.

??

Feeling the Monday blues? Here's a reflection from our writer who volunteered at MINDS to perk you up.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.