China media are recasting and reiterating protest events in Hong Kong to fit its own narrative and agenda.

This terrifying harnessing of the powers of the internet and social media networks has been reported by The New York Times and Reuters.

How much has information supply changed?

China state media were assiduous in its cleaning up of information (read: censorship) relating to the Hong Kong protests initially when they started 10 weeks ago in early June.

The preponderant Chinese media outfits with broadcasting powers and online entities with narrowcasting abilities have since moved from pure censorship to allowing the protests to be reported to its domestic audience -- but with twists and manipulations of contexts.

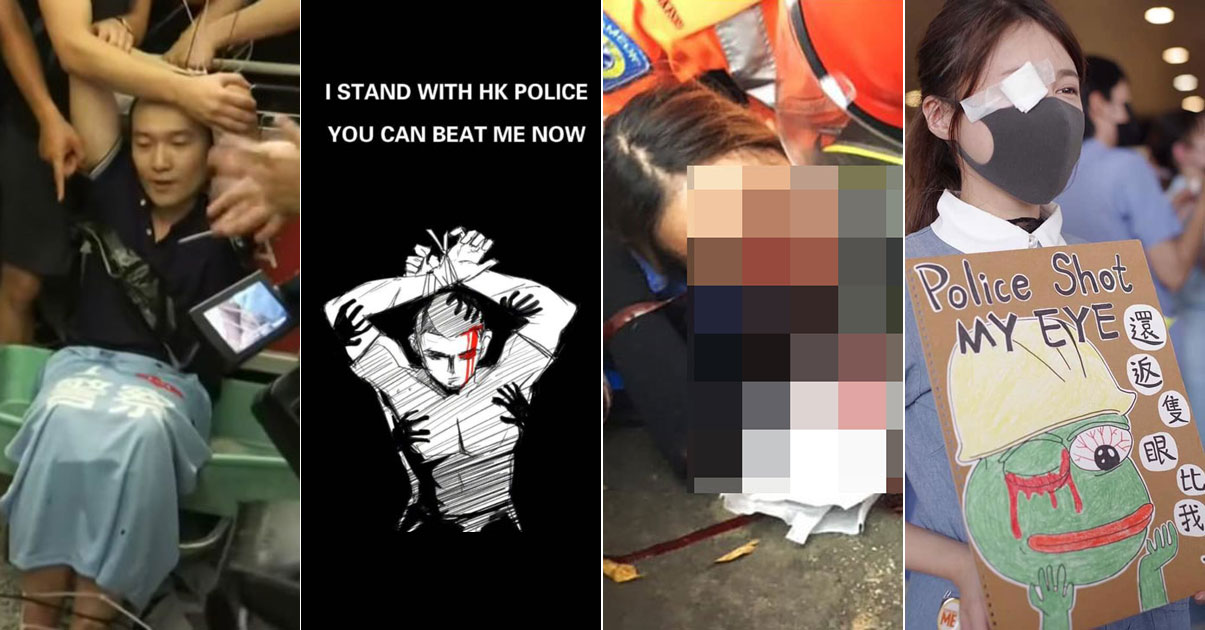

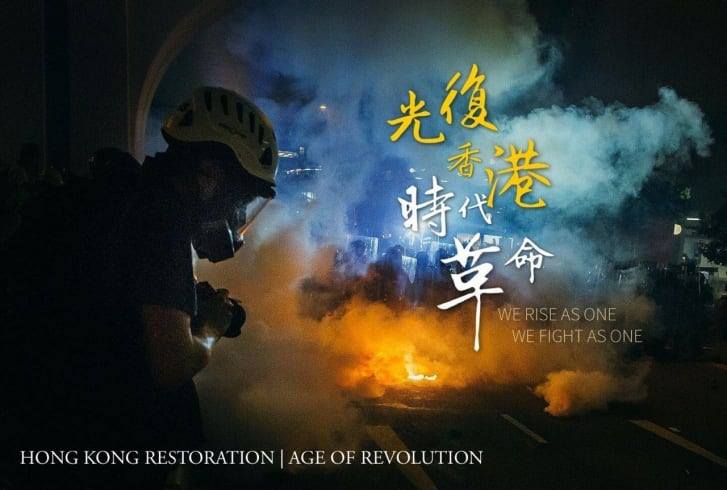

A meme you won't find on China's internet: A positive portrayal of Hong Kong protests

A meme you won't find on China's internet: A positive portrayal of Hong Kong protests

What are some examples of recasting contexts?

On Monday, Aug. 12, state media in China reported that a female Hong Kong protester, who was hit by a beanbag pellet round in the right eye during clashes with the police, had been blinded by a fellow protester.

The situation was difficult to figure out from the get-go, especially ascertaining who it was who fired the round, which was then compounded further by conflicting claims online over how she got hurt.

The Chinese media network’s website went further by posting what it said was a photo of the woman counting out cash on a Hong Kong sidewalk.

The insinuation was clear-cut: As Chinese reports have claimed before, the protesters are merely paid provocateurs engaged by foreigners to sow discord.

What other methods are used to control narrative?

One way to change public discourse is to hear from one side that is particularly aggrieved by the situation in Hong Kong.

On Wednesday, Aug. 14, Chinese state media proceeded to show interviews with stranded travellers at the Hong Kong airport.

This was a marked change from just two months ago where the cause of Hong Kong protests were not even reported in China.

What can be said about these instances?

The most serious charge: China stands accused of manipulating the context of images and videos to undermine the protesters.

The least serious charge: China is telling another side of a multi-faceted story, where China's own domestic audience would hardly be able to recognise the type of reporting of facts from non-state media originating from outside of China.

What else can the Chinese censors do?

Besides actively censoring content, the Chinese censors can actively allow content.

Postings on Weibo, a Chinese social media service similar to Twitter, are now filled with angry responses from Chinese citizens against Hong Kong.

If previously any mention of Hong Kong was removed to keep domestic audiences in the dark, these posts against Hong Kong protesters are allowed to remain and fester, which can create an impression of the abundance of mainland Chinese who are against the protests.

What are some examples of aggressive speech allowed against Hong Kong protests?

“Beating them to a pulp is not enough,” one person said about protesters on Weibo.

“They must be beaten to death. Just send a few tanks over to clean them up.”

Can Chinese media do more than report?

The concept of "fair" and "balance" is not part of the state media's agenda.

This means Chinese state media can and will take sides.

Official media in China have gone online to post messages of support for the Hong Kong police.

"We support the Hong Kong police too!" said a post on the People's Daily's official Twitter-like Weibo account that was reposted more than 500,000 times.

People's Daily is the Communist Party's official newspaper of record.

However, Chinese state media has stopped short of calling for military action to deal with the protests.

What else does China state media do to swing public opinion at home?

Making a hero out of a Global Times reporter.

A Global Times reporter, Fu Guohao, saw his name trending as a hashtag on the Twitter-like Weibo on Wednesday, Aug. 14.

He was tied up and abused by protesters in Hong Kong International Airport, before being let go to be admitted to the hospital.

A short video clip of Fu, with his hands tied behind his head, went viral on WeChat, China's all encompassing messaging system, and Weibo.

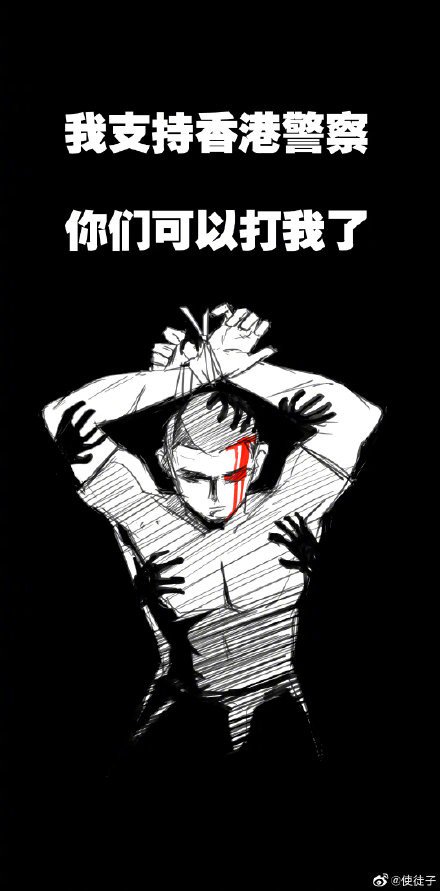

The clip showed Fu yelling: "I support Hong Kong police, you can hit me now."

Does Chinese internet function like the west?

Chinese netizens then shared stylised images of Fu with his quote.

This is basically making internet memes of current affairs of the day, and they then take on lives of their own, far removed from the original context.

The image macros are then shared and reshared.

To be fair, Hongkongers also meme hard as they have adopted Pepe the Frog as a protest symbol, despite the character's alt-right association in the west.

Another meme posted by Global Times read, "Shame for Hong Kong."

One of the most widely circulated images came from a comic artist, Shituzi.

He drew an image of a man with his hands tied and Fu's words, posting on Weibo, "I'm so angry I can't sleep, you can share this image without any attribution."

Fu's words have even been made into a t-shirt.

It is selling for 98 yuan (S$19.37) on Alibaba's online shopping platform Taobao.com.

One user on Wechat, commenting on the clip posted by Global Times, wrote: "Fu Guohao is a real hero!"

What kind of rhetoric is accompanying the Chinese media reports?

This latest flurry of reporting in China comes on the heels of Chinese officials branding the Hong Kong demonstrations as a prelude to terrorism.

China, in the second week of August, condemned some protesters for using dangerous tools to attack police and said the clashes showed "sprouts of terrorism".

What else does China hope to achieve domestically?

In China’s version of events, the Hong Kong protests are a result of a small, violent gang of protesters who do not have the support of residents.

These bandits are paid by foreign agents to provoke and are calling for Hong Kong's independence, while tearing China apart.

This has successfully stoked anger among the Chinese public sympathetic to the government's perspective that law and order must be upheld.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.