Cai Yinzhou is a decidedly unique young man.

He's responsible for interesting initiatives like the Back Alley Barbers, an initiative featured in this year's National Day Parade, where he and other volunteers offer free haircuts to migrant workers.

He also spent his whole life growing up in Geylang, and so wrote an essay recently about what that is like:

But there's much more to the 27-year-old than giving haircuts, saving lives, helping elderly residents move into relocated flats, helping an aunty clear goods in a closing-down sale of her mama shop, and bringing people on tours around his neighbourhood.

And in a bid to understand more about his worldview, and how Geylang fits into it all, we decided to meet him and experience his Geylang Adventures tour for ourselves.

JB Ah Meng

We met at JB Ah Meng, a beer garden coffee shop-turned bona fide zichar restaurant (complete with air-conditioning and sound-proofing panels, a recent addition, mind you) in Geylang, where Cai is a regular customer.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

He recommended we try their signature dishes like the fried bee hoon, stir-fried clams and crispy pork. As he enthusiastically bit into a piece of the pork, he told us: "This is so good. You must try."

In between bites of food, he also paused to say hello to the staff there.

He used to work part-time with them, in fact, briefly in 2017, but he's known them much longer — since 10 years ago.

Naturally, therefore, JB Ah Meng has a special place in his heart, because it was where he hung out and studied (or so he claims!) as a teenager, and he has since forged firm friendships with the staff there.

Back then, the restaurant was located at Lorong 23, where it was more of a beer garden at a back-alley rather than a proper eatery:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BL2TVUrjkQ-/

After the Little India riot in 2013, however, it lost its alcohol license, and as its customer base dwindled, JB Ah Meng decided to focus on food instead, and moved over to its new premises at Lorong 30.

Photo by Jeanette Tan.

Photo by Jeanette Tan.

But the days at Lorong 23 were significant to Cai. They allowed him a glimpse into how people and businesses were conditioned to respond to certain situations — such as fights — in a particular way:

"At the beer garden, there would be a protocol if a fight were to break out. The beer ladies would immediately pour out all the beer into the mugs and keep the bottles. The beer ladies, through experience, realised that bottles could easily be turned into a weapon."

The people he met and befriended at JB Ah Meng would also share information about the goings-on in the neighbourhood regarding illegal activities, fights and police raids.

In view of these, his conservative parents would tell a young Cai "it was better to be safe than sorry" and advise him to avoid certain lanes when walking home.

Did he heed their counsel? He flashed a cheeky grin, and said smoothly that he would still take them anyway.

Having migrant & sex workers as neighbours

We can definitely see how growing up in Geylang has shaped Cai's view of transient, low-wage workers today.

Sex workers were — and continue to be, by the way — his neighbours, and in particular, he recalls a particularly defining conversation he had with one he had met in the lift when he was in Secondary 3.

She had asked him how old he was, and when he told her, she said she had a son who was around his age.

That encounter, as well as numerous other everyday experiences he shared with foreign low-wage workers, made him realise that just like us, they are all individuals with motivations, aspirations and lives that cannot, and should not really, be reduced to their jobs.

He didn't stop there though. To better-acquaint himself with his neighbours, Cai played volleyball with Bangladeshi Friends, a leisure group that gathers for matches and competitions once every weekend:

And between 2011 and 2013, he also played back-alley badminton with migrant workers in his neighbourhood. They stopped doing this, however, after they were raided by the police more than once, and some of the workers feared deportation.These years, said Cai, all taught him the importance of "[moving] beyond the language of economics" and considering migrant workers as individuals with aspirations and complex motivations.

Now pursuing his Master's degree in Tri-Sector Collaboration (bridging businesses, governments and civil society) at Singapore Management University (SMU), Cai sees an opportunity to contribute by providing insights to the migrant workers' perspective:

“It is what people often miss out in their quantitative data (where) it’s all about statistics or wages of the worker... But when you ask the worker on the ground, it’s a lot more complex and dynamic. They base their decisions more on personal motivations. Like their grandmother is ill, or their father had a stroke and they had to stop studying to come here and work... It’s something that you can’t quantify on paper.”

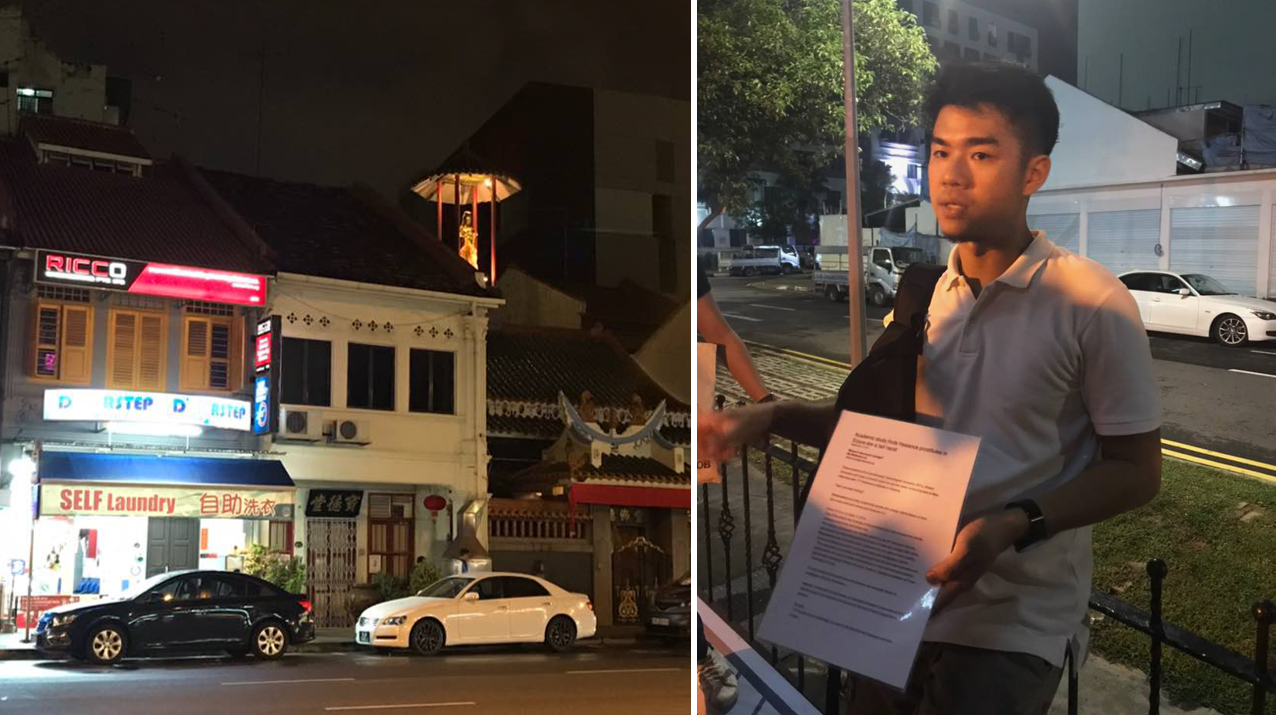

An in-depth introduction to the secrets of Geylang

So it was this multifaceted understanding Cai had of his not-so-typical neighbours, as well as the desire to share this unique perspective with others, that led to the genesis of Geylang Adventures in 2014.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

He leads small groups of between three and 10 people on this guided tour that takes place two to three times a week.

Each participant pays a fee of S$35 (S$40 on weekends), and that, he said, is his sole source of income at the moment.

Cai said he started this in an effort to describe, in the context of a unique microcosm of Singapore's only legalised red light district, the ecosystem of a neighbourhood and the relationship between locals, migrants and the state.

And, he added, he hopes to kickstart conversations on how locals and migrants interact within a place.

So our tour started with this back-alley:

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

We set off at around 7:20pm, and a seasoned Cai expertly led our group through a wide range of back-alleys, just like this one, in Geylang.

Often speaking softly, he guided us to pay attention to blink-and-you'll-miss-it details in the environment that we would otherwise not have noticed. He also nudged us to observe what is absent or present in a physical space, and pick up on various smells and textures.

Cai's tight-knit relationship and familiarity with the people in Geylang is thoroughly impressive — he brought us to places we never expected to see; some were even happy to welcome all of us strangers into their homes or their personal spaces.

We couldn't help but notice also the way Cai greeted different business owners and people from all walks of life, many of whom affectionately referred to him as "Ah Boy".

Like this uncle, who owns this seafood restaurant — one of our stops, because it has a beer garden:

Photo by Jeanette Tan.

Photo by Jeanette Tan.

The problems migrant workers face

Through our conversation with him, Cai emphasised the role of the community in equalising migrant low-wage workers and locals.

He pointed out two main problems that migrant workers in Singapore face: exploitation in terms of injury and wage issues, and the social divide between locals and migrant workers.

Touching on the divide, Cai noted, for instance, that migrant workers try to stay away from places where locals frequent. This includes eating out at hawker centres, even if they are able to afford the food there.

"They often apologise when approached by locals for fear that they are getting in the way," he added.

What makes things tougher is the language barrier and in some cases, not knowing where to go to seek help when problems come up. Cai said he refers the people he meets who need assistance to organisations like TWC2 and Healthserve.

“Sometimes it’s language, sometimes it’s access to information. But workers who have been here longer are quite resilient -- They know what to do in circumstances like these… But many of them operate on the assumption that locals will not help them. That’s why they have to self-organise.”

And they do indeed — some workers have gathered and formed self-help groups to assist newer arrivals, while others volunteer their spare time (as if they aren't exhausted enough from work) at existing organisations.

There's much to be discovered in the neighbourhoods we live in

Through his Geylang tours, Cai works to bridge the gap between them and locals. However, of course, he is also fully cognisant that an experience like this should not just be limited to Geylang.

"I’m working myself out of Geylang to not be a Geylang-specific project," he said, adding that he has already started bringing the Geylang Adventures concept to schools.

He is currently working to start trails or programmes where students can get to know their neighbourhood, and subsequently, even start CCAs (co-curricular activities) to improve the state of social issues:

"We are also looking at working with schools… To start trails or looking at models of trail development where we identify assets within the community and design a tour in their neighbourhood to talk about social issues. But parallel to that, to also have CCAs that improve the state of social issues. It’s something that’s evolutionary, not like a classroom exercise that they do on paper!"

In all this, Cai is very clear on one thing: each project must always be grounded in a particular neighbourhood — preferably surrounding where the participating school is.

"If you want someone to do something about that, they must have stakes in the community… The only way to do that is to discover these (social issues) by yourselves!"

S'poreans can afford to be less insular

When asked about his hopes for Singapore, Cai was quick to point out the strengths of Singaporeans:

“I think the strengths of Singapore is that we are very globalised. Our young are very equipped and aware of issues."

A but follows quite quickly after that, though:

"But I think we are also becoming a lot more insular.”

Back to the topic of social issues, Cai cautioned against the temptation to segment people along certain lines, such as income or social class.

He also said he feels that we have more to do in terms of “seeing people beyond the ‘diversity’ as we have narrowly defined them to be”.

Photo of Cai with migrant workers. Photo courtesy of Cai.

Photo of Cai with migrant workers. Photo courtesy of Cai.

So, how can Singaporeans help?

His remarkably simple response: “By seeing!”

As simple as saying hello to them, acknowledging their presence and existence, learning their names, asking them about their day and how you can help them.

It may be hard to imagine that Cai spent all those years of his life speaking to people from all walks of life in Geylang (which many of us do, we shamefully admit), and building meaningful relationships with many of them too — so many leaps from one's comfort zone (especially that of a painful introvert) that it gets tiring to contemplate.

At the same time, it's worth knowing and recognising that not everyone can step up and out as readily as Cai did, and continue to do so for various groups in need all over Singapore — not just in Geylang.

Top photo composite image, photos by Jeanette Tan.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.