Yayoi Kusama's Life is the Heart of a Rainbow ended its three-month run at the National Gallery on Sunday, Sept. 4.

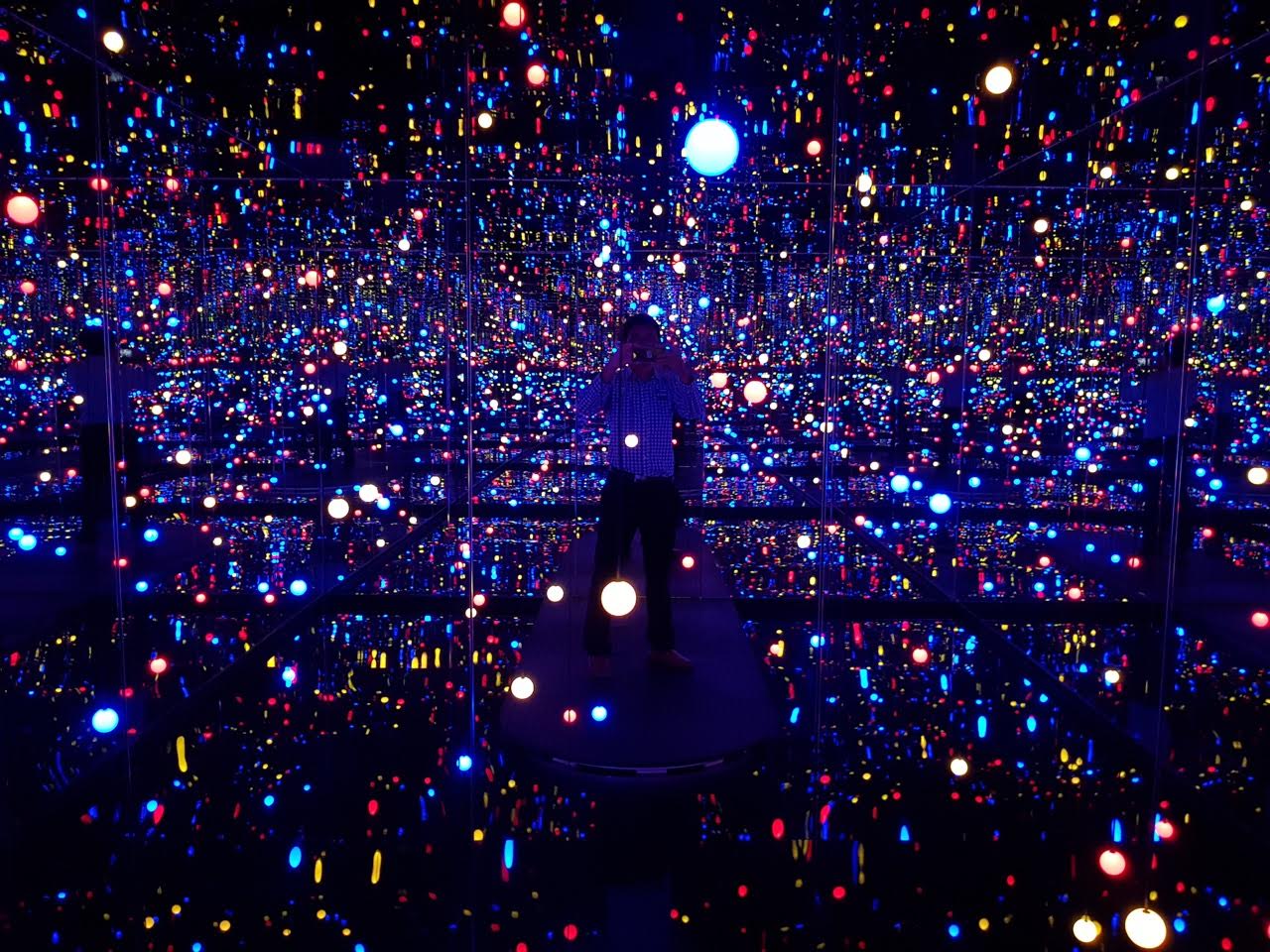

The visual spectacle was wildly popular. Huge crowds showed up and flooded social media feeds with photos of Kusama's polka-dot backgrounds and Infinity Room.

However, when I asked my friends who posted these photos what they thought about the exhibition, their reply was, "I don't get it", and thus, they "do not like it".

Contemporary art is easy to understand with some effort

Now, it is of course not wrong to dislike an artist or an artwork.

But I feel that a lot of the criticism around contemporary art by Singaporeans today is unfair.

Its subjects are actually -- ironically -- much easier to understand than the distant monarchs or biblical figures in Renaissance art, because they deal with modern-day issues and questions we mull over every day.

Perhaps for some of us, we "do not get it" because we're trying to look for what has never existed in these works: a lifelike and anatomically-accurate subject. And when we inevitably do not find them, we unfairly label them as "ill-disciplined" and "elitist".

For Kusama, her art is an abstraction of her individual emotions and ideals (particularly those of feminism and existentialism) which is presented by her favourite motifs -- the polka dots, mirrors, colours and pumpkins -- and, of course, imagined differently by everyone.

Deciphering the polka dots

Photo of Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room (2002) by Goh Wei Hao

Photo of Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room (2002) by Goh Wei Hao

And that is why we might never fully "understand" and relate to the inspiration behind Kusama's works. Because a quick Google search of Kusama will return with results of her struggle with neurosis: upon her return to Japan in 1973, she committed herself into a mental asylum, where she remains to this day.

She once said in an interview that her artwork is an expression of her life, particularly her mental disease -- something most of us are blessed with ignorance about.

The High Priestess of Polka Dots became obsessed with repetitive dots because it approximates the hallucination she had as a child. Also, this obsessive-compulsive pattern is both a manifestation of and (more importantly) therapy for her mental disease.

Kusama has described the process of applying numerous, similar-looking dots as “calming”. And by the 1960s, her now-iconic motif became a “way to obliterate the self” -- inviting the visitors to her Obliteration Room to help return the white room, and even themselves, to “nothingness” using circular, brightly-coloured stickers.

Photo of paintings from Yayoi Kusama's My Eternal Soul (2009) series by Matthias Ang

Photo of paintings from Yayoi Kusama's My Eternal Soul (2009) series by Matthias Ang

The rest of her curated works are displayed in Life is the Heart of a Rainbow, following an almost-linear timeline that ends with My Eternal Soul -- a series of vibrant canvases that the once-prolific artist creates from the asylum she resides in.

If you had taken time to study the write-ups for her artworks, you would have understood how her creations developed over the years, and how her state of mind evolved (or devolved) as time passed as well.

[related_story]

Experience her art, not understand

Yes, understanding the inspiration and intentions behind Kusama's art would help us to appreciate them better. But whether we "understand" it or not should not determine the positivity or negativity of our experience with art -- not just hers, but in general.

Because like with music, where we never ask what's the story or who's the subject is, and we are just satisfied with letting the sound waves evoke in us nuanced emotions, we should not expect art to have to answer these questions for them to be termed "good".

And I believe that this is exactly why Kusama’s enigmatic work has endured -- they refuse paraphrase; her works were never created to conform to any aesthetic theory or to be relatable to everyone else. Instead, Kusama's art is an abstraction of her equally colourful and tortured self, and she does it because it makes her happy.

So, let us stop trying to interpret Kusama's artworks just because we believe that art requires a life-like subject, or because it needs to be "understood".

Understanding is great, but if we can't, let us instead just let Kusama's patterns, colours and mediums enter and wash over us -- like how the melodies and rhythms of music do -- so we might experience the same unruly obsession and emotions she purged and enshrined in her artworks.

Photo via National Gallery Singapore Facebook page

Photo via National Gallery Singapore Facebook page

Now, all that said, personally, I did not enjoy the exhibition -- not because of the artworks but because of the environment they were displayed in.

A lot of Kusama's artworks, particularly the ones that employ psychedelic colours and repetitive dotting, were created in a trance-like state.

However, it was impossible for me, and I believe any other visitors, to be lulled into this same trance because of how noisy the gallery was. And I couldn't take in many of the artworks properly as my view was often obstructed by visitors taking photos with them, one after another.

Photo via Didivacation

Photo via Didivacation

But the biggest irony is that in our incessant need to document everything we see (and every pose we strike for a photo) on our smartphones, we might have missed out not only on the small details -- like Kusama's obsessive-compulsive inspiration behind her polka dots -- but also the biggest takeaway of the exhibition: experiencing her artwork.

And it is only when we properly appreciate the artwork, by experiencing it correctly -- on its own terms instead of comparing it to other works of art -- that it will be fair for us to decide if we truly like an artwork or not.

Photo of Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden (1966) by Matthias Ang

Photo of Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden (1966) by Matthias Ang

Thankfully, at least one of Kusama's work was properly appreciated: the Narcissus Garden, named after the Greek god who drowned because he was too in love with his own reflection.

Its social critique may have dwarfed in meaning over the years, but the prevalence of social media has amplified its narcissistic undertones: seduced by their own reflections, visitors cannot help but snap photos and post them to their social media.

Here are some totally unrelated but equally interesting stories:

This video shows that adults can take the fun out of growing up, but kids will always be kids

Enhanced Internships — The next big thing? Two poly grads share their experience

Quiz: What kind of Singaporean will you be in a crisis?

Top photo by Matthias Ang for Mothership.sg

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.