More than what's happening in the rest of the world, or terrorism, the economy or public transport, diabetes is so important on the government's mind that it was one of only three issues Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong addressed in this year's National Day Rally.

On Friday, August 25, the TODAY newspaper put out an article amplifying this message.

Titled "War on diabetes: Changing eating habits of Malay, Indian communities an uphill task", it ventured guesses as to why statistically, Singapore's Malay and Indian communities have a higher incidence rate of diabetes (For Singaporeans above age 60, 6 in 10 Indians and 5 in 10 Malays) compared to the Chinese (2.5 out of every 10).

It's understandable they're trying to tackle an issue that's affecting some communities more than others.

But here are some of the points raised:

1. Only Chinese dishes can be modified with healthier ingredients

For one, the article suggests, very early on, that only Chinese dishes can be made in a healthier manner or with healthier ingredients — which, of course, is not true.

For them, unlike Chinese dishes, one cannot produce a healthier, yet still tasty ayam penyet or roti prata by simply using less oil, salt or sauce.

2. Indians and Malays only eat unhealthy ethnic food all the time

For this part of the article, they interviewed an Indian restaurant owner, a nasi lemak stall owner and a diabetic who struggles to change his eating habits.

One area that needs to be addressed is their eating habits, even though those interviewed acknowledged that it will be an uphill task.

Mr Rathinasamy Murugesan, owner of Greenleaf Cafe, an Indian restaurant in Little India, pointed out that many Indians eat a lot at one go, three times a day. They also tend to prefer 9pm dinners, which are close to bedtime, and need to round off their meals with a satisfying, sugar-rich dessert.

“My Chinese friends would take the Indian sweet, and (throw up) because it is too sweet for them, but we Indians can take four or five of those,” said the 44-year-old.

...

Taxi driver Hartono, 56, is one of those who find it difficult to change his eating habits even though he is a diabetic.

He loves the rendang that is chock-full of coconut milk, and believes that Malay food should be all about “the colour and spice”. He finds such Malay dishes much more attractive than the “bland” soups, steamed food and stir-fries common in Chinese cooking.

While his wife, a nurse, and his doctor often chide Mr Hartono for his food choices, the man himself finds it just too hard to give up his beloved buffets and nasi briyani. After losing weight during the fasting month by eating mainly cereal, it was “back to square one” after the Hari Raya season, no thanks to all the feasting during festive gatherings and wedding banquets.

...

For Madam Mizrea Abu Nazir, 45, “nasi lemak would not be nasi lemak” without coconut milk, and her stall usually uses two litres of coconut milk to cook a large pot of the rice.

Her family owns the popular Mizzy Corner Nasi Lemak at Changi Village.

While she does not mind cutting down on coconut milk on request at special events, the reality is that people often ask for “more”, rather than less.

“In our lontong, ayam lemak, most of the cooking is about using a lot of coconut milk and oil. At the moment, I don’t (see the need to change) because everyone is still enjoying what they eat… That’s how it is,” Mdm Mizrea said.

3. Chinese people live healthier lifestyles than Malays

The article included just one interview that brings up this point, without expanding on or bothering to add any disclaimers.

While the quotes below do clearly come from the interviewee, a diabetic, it certainly can't be sufficient to back up the argument they're making:

“The doctor talks like it’s very easy (to change), but our lifestyle is not like the Chinese lifestyle. For them, they go qigong, they go exercise ...”

“Our culture is different, we like to gather and cook, go picnic, go makan... You see (the Malays) carrying their pots to Changi Village to go there to eat, sleep, swim (all day),” he said.

The Internet Reacts

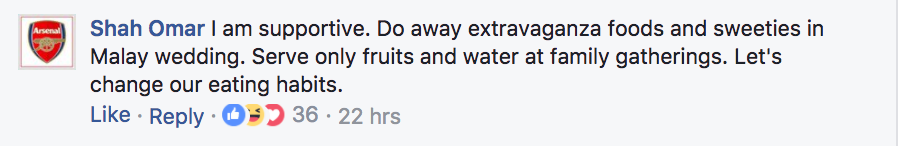

Needless to say, people were very vocal about this:

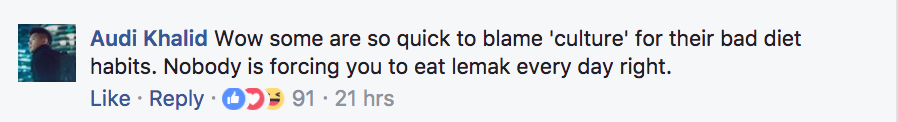

Screenshots via TODAY's Facebook post

Screenshots via TODAY's Facebook post

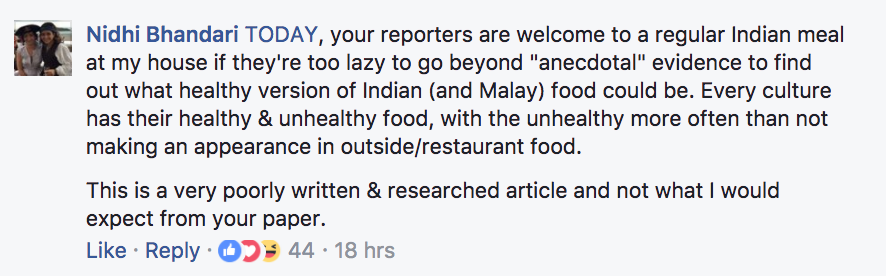

Some were even keen to invite the article's authors to come down and have a good (healthy) meal with them:

Screenshot via TODAY's Facebook post

Screenshot via TODAY's Facebook post

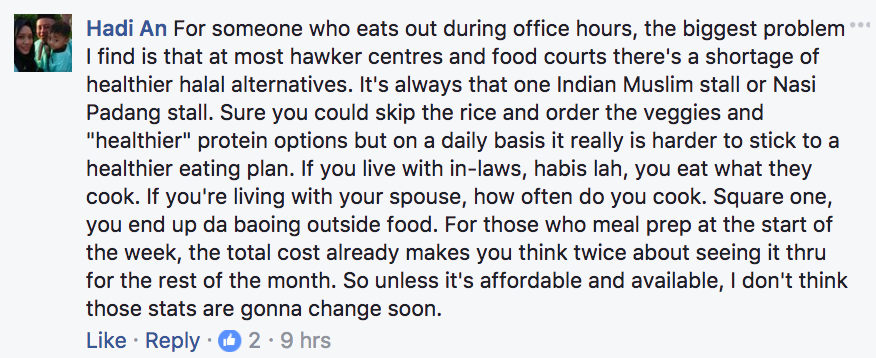

Better still, at least one offered a good point, which is that perhaps it's also about the availability of halal options in food courts and hawker centres, and the cost of cooking more healthily:

Screenshot via TODAY's Facebook post

Screenshot via TODAY's Facebook post

Not a new discussion

This isn't the first time Singapore's racist health narratives have been called out either.

A letter by one Fadli Bin Fawzi back in 2015 flagged two articles in The Straits Times (one in 2010, and another in 2014, both of which singled out the Malay community as being the "unhealthiest") as an example of the not-so-subtle attempt to racialise the health issues Singaporeans face as a whole.

Certainly, Fadli acknowledges, ethnic-specific issues should be factored in to some extent, but discussions on racial habits and lifestyles end up dominating the Singapore approach to health issues:

Take, for instance, the construction of obesity as a “Malay problem”. Such narratives localise obesity as a “community problem” and blame Malay cultural practices or habits for the community’s high incidence of obesity. This approach is not only insensitive but also too simplistic and reductionist to truly resolve the issue.

And mainstream media have long echoed this, as suggested by Fadli:

For example, the 2010 ST article blamed Malay cuisine and dietary habits, with its “glistening with coconut saturated rice” and “delightfully rich, sinfully sweet melt in the mouth kueh”, for engendering Malay obesity. Even Malay gatherings such as weddings were faulted. Such celebrations were seen to promote the consumption of richer and fatty food, ignoring the fact that the occasional festive indulgence is common throughout many cultures.

He rightly also points out that other socioeconomic factors come into play when it comes to diabetes, such as income, affordability, and choice — these, in turn, should be given wide play in any discussion on the topic too.

Solution?

It's often been argued that racially-defined statistics helps our government determine more targeted policies to better-assist Singapore's various communities.

Blaming the high incidence of diabetes on Malay and Indian food, culture and lifestyles is not just a sweeping generalisation, but can also turn out to be a superficial way of tackling a complex problem that also finds socio-economic issues at its root.

This also eclipses the importance of Singaporeans of all races taking note of their diet and habits, not just in communities where it's identified as a prevalent issue.

Here are some totally unrelated but equally interesting stories:

These S’poreans prove that you don’t need superpowers to be a hero

An East-sider’s guide to spend a day like a tourist in the east

Top image adapted via sharonang on Pixabay and TODAY's Facebook post

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.