We don't need an actual time machine to experience the past. All we need is a good story to launch our imagination into the great beyond.

A group of NUS students took on the challenge of reconstructing the past (specifically 1930) through a collection of short stories, as part of a module in school.

By using information from a variety of sources, and supplemented by a good dose of imagination, they created short stories which will transport you back to 1930.

One of those writers was Choo Ruizhi. His story, Flying Solo, is based on an adaptation of real life historical figure Amy Johnson, a British pilot who was the first female to fly alone from Britain to Australia in 1930.

Amy Johnson is the central adapted character in Choo's time-travelling story. Image via

Amy Johnson is the central adapted character in Choo's time-travelling story. Image via

In his story, Choo names his character Amie Jon-Son and makes her out to be a time travelling bioanthropologist who made a pit stop in Singapore:

Excerpt from Flying Solo by Choo Ruizhi

In 3016, the Faculty of Bioanthropology at the New University of Singapura (NUS) had finally granted Amie Jon-Son permission to resume her fieldwork, this time to go where no time-traveller had gone before, in the pursuit of knowledge. Unlike casual time-tourists, who treated the past like a foreign country merely to be gawked at, academics at the New University of Singapura had taken time-travel to dizzyingly dangerous heights and directions. Historical bioanthropology had been one of these directions.

Oh sure, the past was a foreign country. It was full of strange peoples, with their alien cultures and bizarre rituals. Understanding them on their own terms had always been the work of the anthropologist, and the historian.

But how did animals in the past think

In the year 3016, this was no longer an absurd question. The biotranslator had revolutionized human-animal communication and animal studies. It synthesised the olfactory, aural and visual cues of lifeforms into a system that allowed humans fluent communication with virtually any organism on earth. That had, however, not been enough for the researchers at Singapura. Unsatisfied even with the prodigious leaps they were making, they wanted to find out how animals in the past saw the world.

We spoke to Choo to find out more about his experience writing historical fiction.

1819: What do you think is the appeal in historical fiction?

Ruizhi (RZ): I think people read and tell all sorts of stories for all sorts of reasons. If I had to guess, I think the better attempts at historical fiction give people a sense of really being in a somewhere which once existed, of re-living a moment which apparently, actually happened.

If you look at the two words, the combination is almost oxymoronic, contradictory. History tries to be as faithful as it can to what "actually" happened, whereas fiction creates and invents, often with a gleeful disregard for reality.

I think one of the many appeals of historical fiction is that it occupies this gray area between what is recorded as fact and what has been imagined as fiction.

Sometimes historical fiction appears so real, and the story is so emotionally compelling, you almost want it to have happened.

The Singapore River features in Choo's story. Image via National Archives.

The Singapore River features in Choo's story. Image via National Archives.

[related_story]

1819: What was the biggest thing you took away from the module?

RZ: Tangibly, and practically speaking, I think the class gave us all an insight into the tan-jiak of the historian - into the meat-and-bones of historical research.

How and where do you find historical information about Singapore? How do you then organise vast loads of information and craft it into something interesting and exciting?

Mosquito bus in 1935. The writers in the module base their stories on everyday photos and documents of the past. Image via National Archives.

Mosquito bus in 1935. The writers in the module base their stories on everyday photos and documents of the past. Image via National Archives.

On a more personal level, I thought this class was quite literally an exciting trip into the past. I never realised so much existed on how people lived nearly a hundred years ago!

From the price per kg of stingray, to how much specific gardeners at the Botanical Gardens was paid, to the life (and death) stories of different segments of Singaporean society - right down even to how much you needed to pay for a bus ride say, from Jalan Besar to Lavender Road.

Excerpt from Time and Death by Jean Heng

Ma, you think next time when I’m a slightly older I will be able to go to school like kor?” she asked, hopeful that the answer will be different this time round.

“I’ve told you many times, girls don’t go to school, they are supposed to stay at home, and learn how to cook and clean,” her mother would respond wearily, “who else will help me take care of your two brothers?”

She knows that this is only partially true: she has seen girls in school uniforms, clutching textbooks about language and history and literature; but she knows her family simply can not afford to send her to school. After years of pleading with her mother, she has come to the realization that she is unable to change her fate. This gradually transformed into hatred towards me – there are days when she will dream of being born in a separate part of me, when girls are not bound under such social constructs and financial constraints, when they can learn and play without worry or burdens. She will dream, before throwing a curse at me for being cruel and unrelenting. I wish I could tell her that I am more than what she can see and understand, that she has the capacity to go beyond the boundaries set upon her, but these are things she will learn as she walks with me.

. . .

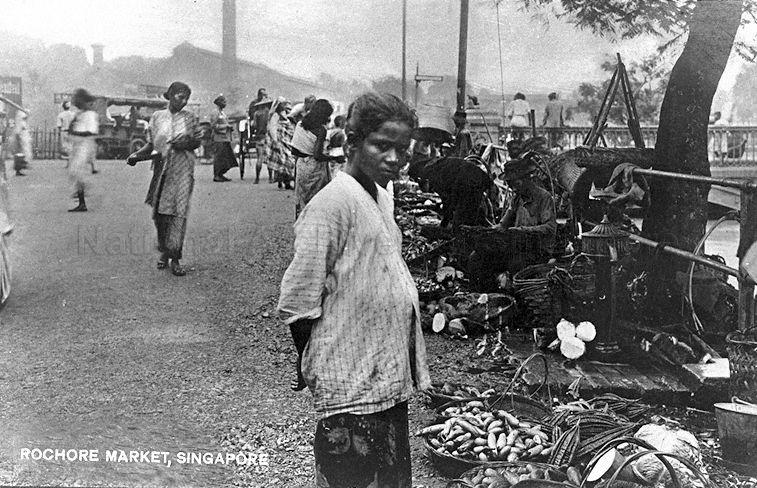

Located at Crawford Street, the Rochore Market is typically busiest in the wee hours of the day, at around six or seven in the morning. I have no off days there, as the market opens daily, selling items ranging from vegetables and meat, to curry spices and sundries. It is typical to observe wet floors, miniature weighing scales, and straw baskets. Zhen arrives slightly past eleven: the market is relatively empty, and most of the items left are imported foodstuffs like rice and coffee. She heads over to her usual fishmonger and asks for the two small stingrays left on the pile of ice. He has a white towel slung across his neck, soaked by the sweat accumulated since morning. His face is unshaven, his fingernails filled with grime, and god knows when was the last time he took a proper shower.

The fishmonger places the stingrays on the weighing scales. “Sixteen cents. Your kor today got exam again ah.” She smiles and nods; frequent visits to the market has allowed her to forge some relationships with the food sellers, and she appreciates the fact that they can tell what is happening at her family based on the items she is purchasing. The fishmonger wraps the fishes in newspaper, and then hands it to her, together with the change, which she keeps in a special cloth pouch.

The stories brings history from the perspective of the everyday man, involved in everyday activities, such as shopping at the market. Image via National Archives.

The stories brings history from the perspective of the everyday man, involved in everyday activities, such as shopping at the market. Image via National Archives.

1819: Tell us more about the writing process. Was it difficult finding historical material to inform your writing?

RZ: The module, known as HY4227: Sources of Singaporean History was structured around three assignments, of which the "Short Story" component was actually the last.

The first section of the module required all of us to go out, research and present on sources like newspapers, colonial government records (such as burial registers, census, statistics and departmental reports), as well as postcards, memoirs and photographs. Where could these documents be found? What information was in them? What were they not/useful for?

These were some of the things we had to present to our classmates.

[related_story]

Having familarized ourselves and our classmates with the different sources of Singaporean history available, the second segment of the class focused on specific topics. From the rubber industry to animals to the transport system to diseases, any topic was fair game, so long as you could find enough information on it.

"Tell us everything there is to know about this topic in Singapore in the year 1930" was more or less the only direction we were given. We each had to write a topic paper and then present our findings to the class.

In this way, bit by bit, we all helped to create an emerging picture of what 1930 Singapore looked, smelled, and sounded like: from its automobiles, to the food people ate, to the languages which were spoken, down to the types of toilet bowls available in that time.

By giving a voice to the ordinary lives of the people in the past, these stories let us view a side of history that is often eclipsed by the personalities from our history books. Image of Chinese family by National Archives.

By giving a voice to the ordinary lives of the people in the past, these stories let us view a side of history that is often eclipsed by the personalities from our history books. Image of Chinese family by National Archives.

Finally, the third and last part of our class challenged us to put all this shared information together, and organize them into a coherent and compelling narrative that was as imaginative as we could make it, while at the same time being historically accurate and detailed.

The historical material available was surprisingly rich. The British were very meticulous, almost obsessive, in the level of detail they recorded of their colonial subjects.

For example, you could find out the daily schedules of prisoners, and even what they ate at what time. Local newspapers also provided an insight into the events which were happening around the city in 1930.

You could even find out how much an elephant cost back then, if you wanted to purchase one from the Punggol Zoo!

While we had to sift through (quite literally) thousands of pages of these documents, most of what we worked with could be found online, either in the records of the NUS Central Library (CLB), or NewspapersSG, the online local newspaper archive, or at the National Archives of Singapore.

Librarians and archivists at the NLB, CLB and NAS were also very helpful and resourceful if we needed help looking up particular details of a topic.

To read the rest of the short stories, head over here. There are six different categories, including crime, science fiction, and even personification (we love the thinking rickshaw). Happy time-travelling!

Here are totally unrelated but equally interesting articles:

The Kiasi guide to surviving a mass attack of any kind

4 real life versions of comic book superpowers you used to read about in your childhood

Top image is of Hock Lam street in 1969, via Singas.uk

1819 is a labour of love by Mothership.sg where we tell stories from Singapore’s history, heritage & culture. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter!

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.