Along a steep uphill slope, somewhere in Bukit Timah, stands Peter Lee's house, which you can't see much of from the tall wood-metal gate outside even though it's actually huge.

Now 54, Peter has lived up that hill all his life, and the land the house stands on has been home for his family, the Lees, since 1958. Not the Lees who ran/run our country, but a Lee who once shared office space with the late Lee Kuan Yew's law firm, which the founding Singapore prime minister set up with his brother and late wife.

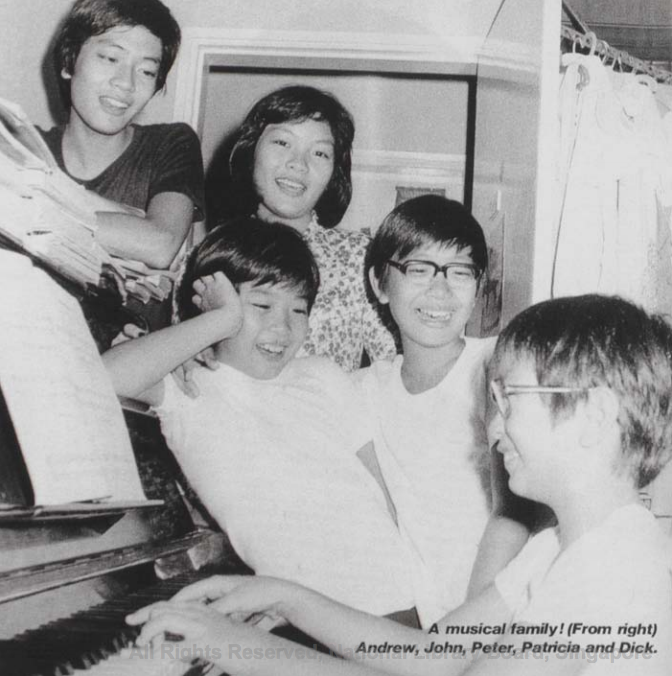

The Lee siblings (from left: Dick, Patricia, Peter [leaning against the piano], John and Andrew), in album artwork from Dick Lee's "Life Story"

The Lee siblings (from left: Dick, Patricia, Peter [leaning against the piano], John and Andrew), in album artwork from Dick Lee's "Life Story"

This Lee we're talking to today is the third of four sons of retired shipping businessman Lee Kip Lee. His oldest brother is the one most of us will know: Cultural Medallion winner and decorated composer Dick Lee. He also has two other brothers — John, who is older, a vocal coach, and Andrew, who is younger, a graphic designer. He had an older sister, too: Patricia, who passed away in a car accident when she was 24.

Lee himself, alongside all his brothers, is not spared from a life immersed in culture and the arts. A self-confessed hoarder, his penchant for "all things beautiful" was cultivated in him by his late mother Elizabeth.

He has after several years of higher education and work in China, London, and Hong Kong, enjoyed the privilege of travelling the world, the region and the island, acquiring all kinds of historical artefacts relating to Singapore, Asia and Peranakan culture, history and heritage.

And this has morphed him into the person he is today: the family's resident historian, cataloguer (he'll throw in "busybody") and donor of massive collections of rich swathes of Singaporean history and culture.

Lee shares that his parents were pleased to embrace the shared passion their children had for music, performance, and the arts — he, John and Andrew were in a cross-dressing three-boy band that performed on a TV show in the 1970s, for instance:

A New Nation (the original, non-satirical one) article dated Aug. 20, 1975. Peter is the sultry poser in the middle. Courtesy of Peter Lee

A New Nation (the original, non-satirical one) article dated Aug. 20, 1975. Peter is the sultry poser in the middle. Courtesy of Peter Lee

We asked him why Dick wasn't in the group — Lee responded cheekily, "He couldn't pass our audition!"

"It was so crazy. I wonder why my mother let us do all these things. She was really unconventional. It was the kind of nonsense. She just loved fun and she allowed us to express fun in any way."

The extravagance the Lees enjoyed in exploring all kinds of interests in their childhood — and we're not referring to material extravagance, here — extends to Lee's home, a mansion filled with intricately-made, painted or carved items and furniture to gaze at and ponder at every turn.

Take this Dutch settee, for instance, made in the 18th century by Asian craftsmen:

Photo by Chiew Teng

Photo by Chiew Teng

And these "Namban" lacquer boxes, made with mother of pearl inlay, were likely made in Japan in the 16th and 17th centuries for the Portuguese market. Lee says this based on the design on the front latch, which if you notice is aligned to the left of centre for the placement of a lock, apart from the key hole in the centre:

Photo by Chiew Teng

Photo by Chiew Teng

There were also chairs and chests made from ebony, seemingly plain brown boxes of rare knotted Ambon wood, and plenty more where those came from.

It was tough for us to tear ourselves from this antique wonderland, as well as a studio chock-full of treasures in exquisite hand-woven and painstakingly-dyed cotton batik, old photographs of 19th and early-20th century Singapore, among a host of things we hadn't the time to see, and his six wonderful dogs — four rescued mongrels and two French bulldogs left behind by a friend — but we had to get on to our conversation, from which we learned a lot, too.

The Peranakans "think we are God's gift to the universe"

Photo from Wikipedia

Photo from Wikipedia

For a Peranakan who has spent decades doing research into Peranakan heritage and culture, Lee has pretty amusingly disparaging comments to make against his own community.

For one thing, he says Peranakans tend to enjoy claiming credit and ownership over things that aren't actually theirs.

Take the sarong kebaya, for instance, which today is widely acknowledged to be a Nyonya thing. Lee said he knew very well his mother's fascination for textiles, and out of intrigue, embarked on a decade-long research project to discover where it came from:

"It was really... it sort of destroyed all the illusions; it wasn’t Peranakan. The sarong kebaya is not Peranakan. It turns out it was a fashion that was worn by everybody in many parts of island Southeast Asia – Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand. Everybody contributed to this style.

Over time it was sort of abandoned, and became perceived as being Malay, but actually it was worn by people of all communities, and everybody contributed some aspect to it... so it was sort of early globalised modern fashion, and it’s not really Peranakan at all.

There is a late, sort of, contribution, in terms of design and motifs, but overall it’s part of a much bigger fashion story. A multicultural one too!"

The same story applies for kaya, too:

Photo from Flickr

Photo from Flickr

"Peranakans will claim, kaya, you know, srikaya, as being the quintessential Peranakan thing. But having done my research on it, it is obviously something that was created by a Eurasian in probably Malacca because the Portuguese really used egg yolks for dessert in their puddings or whatever. Instead of milk, coconut milk was used. So it’s sort of a Portuguese-styled sweet."

Interestingly, you'll find srikaya in Lisbon, Brazil and other parts of Central America as well, all made from the same egg yolks and milk.

"You’d find versions all over Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and then at a certain point, in Singapore, a lot of the members of the Hainanese community were in the F&B industry, and they worked for families, they opened coffee shops and all that.

So it’s identified as the Hainanese kaya now, right. And now you associate it with Ya Kun Kaya Toast. So it’s quite interesting how it’s evolved and it’s something that everybody claims as theirs. But its origins are so mixed."

The "flawed" idea of identity

All this research Lee was doing — into many other things apart from kaya and kebayas, of course — led him to the conclusion that the idea of a person or group of people having an "identity" is inherently flawed (stay with us, here, it gets a little meta).

He explains that in the 18th and 19th century, people were not too concerned with identifying with one another, and were far more adventurous and easygoing with how they wore their outfits, how they cooked their cuisine and how they played their games.

The idea of people retreating into their own communities and boundaries only happened in the 20th century, he says. With the rise of racism and nationalism, people felt the need to more clearly demonstrate elements of the communities they belonged to through their ways of life.

“If you really think about it. You go like, 'oh in our family we do this and this' but quite often if you do it, it’s because you are forced to do that. It’s not something in your genes, you know what I mean. It’s sort of a habit and people are forced to do, and if you don’t do it, you are the black sheep, you are the rebel.

So it’s about enforced group behaviour. That’s all it is, actually, identity. And saying, 'Oh if I’m Peranakan, I must behave like this so I should do this, I should do that' but it’s all artificial. The natural human tendency is to be inconsistent.”

Identity, Lee argues, is something promoted by governments and academics so it's easier for them to formulate policies and boundaries for study. But the truth is, people just don't work that way.

Think about how your grandma cooks a certain dish in a specific manner, for instance, with certain ingredients, but your friend's family, despite being from the same dialect clan, does it differently, but yet everyone is authoritative about what it should be.

"So when I do talks I emphasise diversity, inconsistency and spectrum because at the end of the day that’s more real. If we do field work, we see that you get a full range for, let’s say, ancestral rites. They will do from A to Z and everything in between. You can sort of, maybe pinpoint a range, of things that might happen... you can even do that for popiah recipes.

People are much more diverse and complex than what historians of the past may have been trying to tell us. That vision of the past has resulted in confusion in the present because people go, 'oh but I’m not 100 per cent this and I’m 20 per cent that'. And the reality is that, that is totally normal.”

The privilege of helping us remember

Looking at a set of traditional European formal clothing. (Photo by Chiew Teng)

Looking at a set of traditional European formal clothing. (Photo by Chiew Teng)

In the largely Westernised world we live in today, it's easy to get caught up in chasing one's career, dressing mostly in Western-influenced office attire for work and receiving many of our formal and casual food and fashion choices from there too.

It is in this world, where appreciation for culture and our history is overshadowed by the need for a secure rice bowl, that Lee finds his place: quietly recording, documenting, sharing — although he isn't yet convinced to go on Facebook to do so — and hoping to make sure we don't forget from whence we came.

"Definitely I feel very privileged to be able to work on this aspect of culture and the arts. On the one hand, it might seem... frivolous and not important but, however, I feel... something that calls itself a civilisation should have memory.

And I think I’m just trying to make sure we don’t forget things, where we come from, who we are. And, whether worrying about our next meal... if we minus off this aspect of our community, it’d be really sad if we don’t even know anything about our past and don’t try to maintain threads to all the different aspects of who we are, especially as something as exciting and diverse as an old port town like Singapore."

Lee also strongly feels that there is an important place for history and culture here — especially if we can learn to discover it in the way it really is: organic, varied and creative, not uniform and handed down strictly and specifically — because of the links we can establish between seemingly different communities.

"The particular aspect of what I’m trying to celebrate in cultural history, would not be the things that I traditionally, an art historian might do, which is to emphasise exceptionalism; what is so special about being Peranakan.

Rather, I’m saying Peranakans are not special, they kind of kidnap a lot of cultural icons and call these things their own, our own; rather to use these things as bridges, things that our community can call our own — a shared heritage."

As the only one among his brothers who was interested in history and his family tree, Lee partnered with Dick in a recent documentary called Down the Line, which gave them the opportunity to take a long trip up to a village in China to meet the community of Lees from which his family descended.

"It was quite interesting. It was really a chance for the two of us, not only to interact on this because I was really happy that he was interested and we sort of went on this adventure together... (but) it was really nice, because I barely see him so it was quite a nice opportunity to spend some good time with him.

We are the most relaxed with each other. Very chill, and we just go and makan. It was a wonderful time. When it comes to other kinds of moments, over family, we might be arguing about something else, and we’re not agreeing about this and that. Family related things, there are other issues and viewpoints, but on holiday it’s so nice."

You can watch the show, which will be screening at the Origins Gallery at the Peranakan Museum from April 28 to May 14, during the Singapore Heritage Festival.

Top photo by Chiew Teng

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

Content that keeps Mothership.sg going

??

How to make your Asian mum proud of you once and for all. Don't say we never teach.

??

Click here for rabak artist impressions of your neighbourhood. Pls don't laugh we tried our best.

??

How long do you take to get to work? Very shag hor.

?️?

Want to go Japan this year or not??

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.