In light of the controversy over the name Syonan Gallery, it is perhaps timely and useful to revisit some events in Singapore's history that reflect the strong sentiments felt by some Singaporeans about the brutality of the Japanese Occupation to this day.

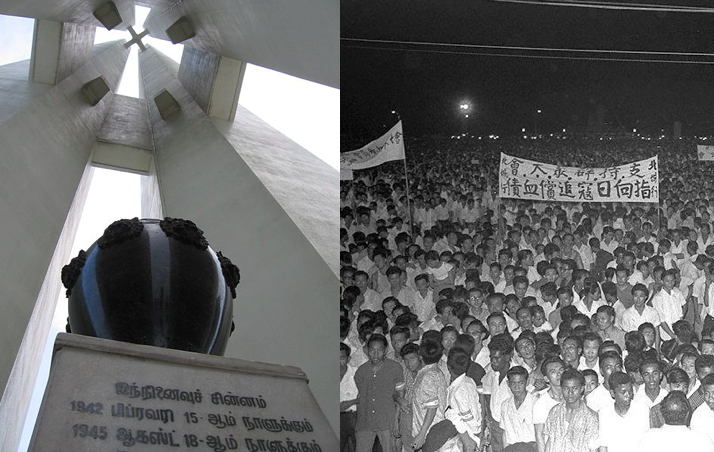

The Sook Ching massacre

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore lasted 44 months from February 1942 to September 1945. Those years were characterised by unimaginable hardship, starvation, torture, and atrocities committed by the Japanese Military Administration against Singaporeans.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] Images of Sook Ching screening centres, photos taken at old Ford Factory by Joshua Lee[/caption]

Images of Sook Ching screening centres, photos taken at old Ford Factory by Joshua Lee[/caption]

Sook Ching, the notorious "cleansing" operation carried out by the Japanese shortly after the fall of Singapore, to rid the local Chinese population of anti-Japanese elements, saw the massacre of many young Chinese men (and sometimes women and children too). Victims' bodies were buried in mass graves at various parts of Singapore, including the Siglap area.

Many Chinese families lost their loved ones, as a result of Sook Ching, and would never know of their true fate, apart from having to accept their demise.

The brutality of the Japanese Occupation was not limited to the Chinese community, however, as there are many other stories of suffering from the Malay, Indian and Eurasian communities.

The official number of victims that the Japanese massacred was 5,000, but many unofficial estimates have placed the actual number between 40,000 to 50,000. Many of the mass graves of the Sook Ching massacre would only be discovered in the years after the war.

In 1962, 17 years after the end of the war and Occupation, many mass graves were discovered in the Siglap area, which led the area to be called the "Valley of Tears" or "Valley of Death".

"Blood Debt" Rally at City Hall on August 25, 1963

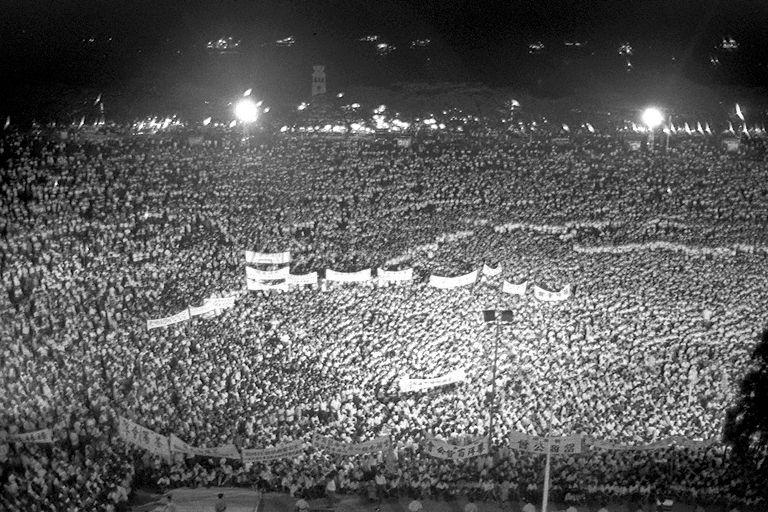

Coming on the back of the discovery of mass graves in Siglap the previous year, a mass rally organised by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (SCCC) and supported by the Singapore government, was held at City Hall (present day National Gallery Singapore) in 1963 to demand that the Japanese government pay M$50 million in compensation or “blood debt” to atone for wartime atrocities its army had committed in Singapore.

Known as the “Blood Debt” rally, 120,000 Singaporeans of different ethnicities turned out at the event. It remains one of the largest rally attendances in Singapore's history. Given that the population of Singapore then was about 1.8 million people, it was also a highly significant event etched in the memories of many older Singaporeans.

Imagine a crowd more than twice the size of the National Stadium's 55,000 seating capacity gathered at the City Hall and Padang area.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="768"] "Blood Debt" rally crowd at Padang. Source: NAS [/caption]

"Blood Debt" rally crowd at Padang. Source: NAS [/caption]

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="768"] "Blood Debt" rally crowd at Padang. Source: NAS [/caption]

"Blood Debt" rally crowd at Padang. Source: NAS [/caption]

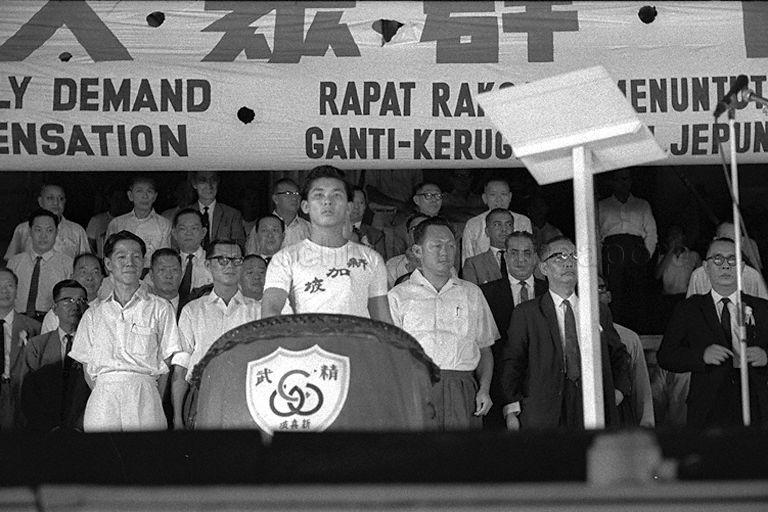

Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew himself spoke at the rally, sharing his own narrow escape from becoming a victim of the Sook Ching massacre. He also said that the government had chosen to back the "blood debt" demand even though doing so would make it difficult for Singapore to attract investments from Japan, which had become the world's second largest economy behind the U.S. in the 1960s, as a result of its post-war economic boom.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="768"] Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (third from right) at the "Blood Debt" rally. Source: NAS [/caption]

Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (third from right) at the "Blood Debt" rally. Source: NAS [/caption]

Also featured at the rally was SCCC chairman Ko Teck Kin together with Malay, Indian and Eurasian community leaders.

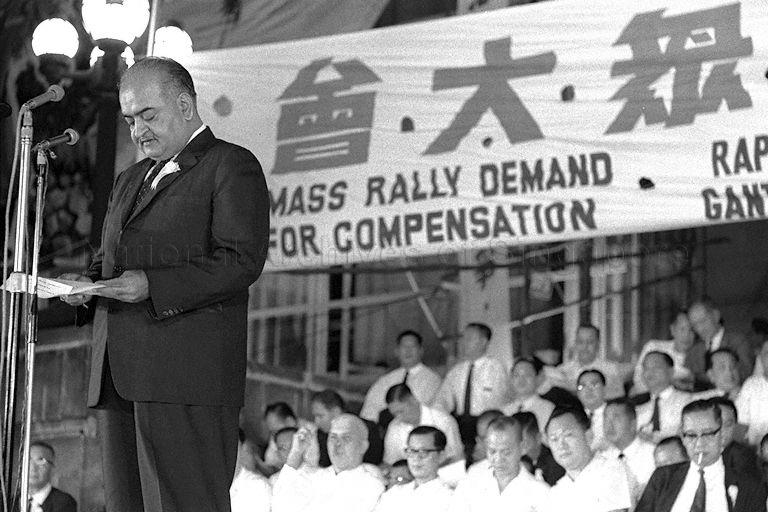

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="768"] President of the Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce D T Assomull speaking at the "Blood Debt" rally. Source: NAS [/caption]

President of the Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce D T Assomull speaking at the "Blood Debt" rally. Source: NAS [/caption]

According to an article on HistorySG, three resolutions were adopted at the rally:

1) There would be an unified effort by the people of Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore to press the Japanese government for compensation for the wartime atrocities committed against the civilian population.

2) If Japan failed to respond, a non-cooperation campaign against the Japanese would be carried out.

3) New entry permits would not be issued by the Singapore government to Japanese nationals until a settlement was reached.

The Japanese government did not respond favourably to the demands, which led the SCCC to start a campaign to stop exporting goods to Japan, and boycott Japanese products in September 1963.

However, the campaign was suspended after then Malaysian prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, agreed to represent Singapore by taking up the issue with the Japanese government, as Singapore was then part of the newly formed Federation of Malaysia.

After Singapore became independent in 1965, the Singapore government continued to negotiate the "blood debt" matter with the Japanese government.

In 1966, the Japanese government agreed to paying compensation in the form of an M$25-million grant and a M$25 million loan on special terms.

The size of the rally crowd in 1963 and the decision by the government to back the event at the expense of attracting Japanese investments were a clear indication that the deep wounds and scars Singaporeans harboured against the brutality of the Japanese Occupation had not healed fully, 18 years after it ended.

Now, 75 years after the beginning of the Japanese Occupation nightmare, it is perhaps understandable that the pain brought about by the Occupation still lingers on in some Singaporeans, as exemplified by the Syonan Gallery issue.

Top image from Wikipedia and NAS.

Related articles

TGIF special: Yaacob Ibrahim apologises; “Syonan Gallery” renamed; Khaw Boon Wan lends sarpork

Internet reacts to the use of ‘Syonan’ in naming WWII exhibition at the Former Ford Factory museum

The Syonan Gallery, Empire Ball, and the Singaporean identity

Here’s what LKY and other founding fathers did when WW2 hit S’pore 75 years ago

On the road to Syonan-to: How Singapore got swept into WW2

Becoming Syonan-to: The brutality of the Japanese Occupation from 1942 to 1945

Here’s how S’pore’s Japanese Occupation survivors endured 3 years of hunger: Part 1

Here’s how S’pore’s Japanese Occupation survivors endured 3 years of hunger: Part 2

Food people ate during Japanese Occupation gets yummy 21st century makeover

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.