“We Built This City” is a new series of feature interviews on Mothership, tracking the contributions and efforts of the pioneers of modern Singapore. In these, we sit down with people who had key roles to play in the foundations of our fledgling nation, and tell their stories of the very grown-up decisions they had to make for the country at very young ages, some known, and some kept hidden till now.

We begin with General Winston Choo, Singapore's first three-star General and longest-serving Chief of Defence Force. This interview was done in two parts, of which this is the second.

General Winston Choo has led quite a life.

If you don't know this no-nonsense but still down-to-earth and occasionally self-effacing 78-year-old cancer survivor, you can read some of the exciting parts of his story here:

For someone like him who has worked for, worked with and hung out with so many interesting and famous people, he's bound to have stories and opinions about them.

In our chat with him, we took the opportunity to touch on some very pertinent issues and people, and he offered his candid views on them.

On working with Lee Hsien Loong, George Yeo, Teo Chee Hean, Lim Hng Kiang, Lim Swee Say

One of the roles given to him in his time as Director General Staff by the late former Defence Minister Goh Keng Swee, which he described as "one of the most challenging" was to oversee and manage the Singapore Armed Forces's scholarship holders.

These guys were the ones primed to go on the fast track for military leadership — and in some cases, other types of leadership too.

Coincidentally, the time Choo spent at the helm of Singapore's Defence Force overlapped with the time several of our third-generation political leaders were growing up.

"Hsien Loong was in the first batch of scholars. He had a respectable good lot of people in his batch. But at first he stood out, not by virtue of who he was, but for the work he did. I mean, I knew him and Hsien Yang when they were boys in the Istana!"

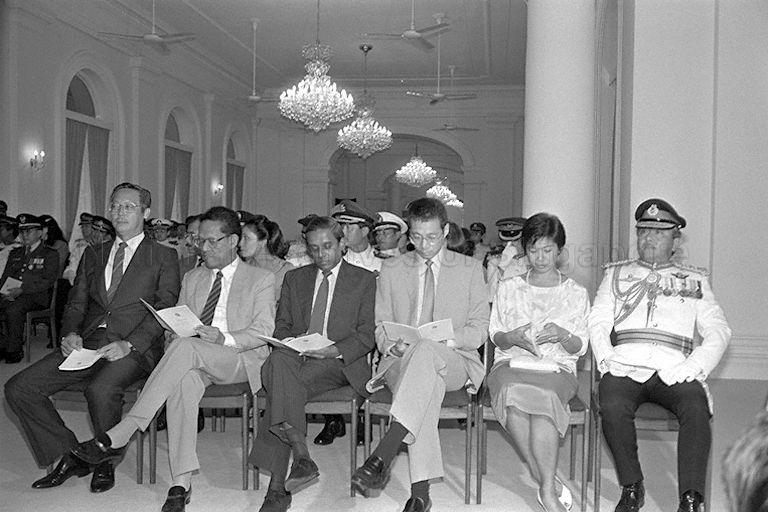

Goh Chok Tong, Ahmad Mattar, S Jayakumar, Lee Hsien Loong, Katherine Seow (Choo's wife) and Major-General Winston Choo. (Photo via the National Archives)

Goh Chok Tong, Ahmad Mattar, S Jayakumar, Lee Hsien Loong, Katherine Seow (Choo's wife) and Major-General Winston Choo. (Photo via the National Archives)

He also describes our Prime Minister as a person who "looked out for things to improve".

"When he was in artillery, he designed an artillery calculator — at a time where people would use pencil and paper to work out data for guns, he had a simple calculator, and he developed an algorithm.

And then later on, he was chief of general staff operations, and he directed the rescue operations on the 1983 cable car incident. He was the man in charge, and in my view, he did very well. He was the one overseeing the fellas who were being suspended out of the rescue helicopter, risking a very dangerous fall into the sea — either themselves or the trapped passengers they were saving. (Any deaths) would not be on the head of the helicopter pilot, you know — it's him (Lee). When we (the SAF) came in, when we did the rescue operations, nobody died. All were saved."

He also had high praise for former Foreign Affairs Minister George Yeo, who he had the interesting opportunity to have overseen and also worked for in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after he retired from the military.

"George Yeo was one of the best, he was a visionary. Even in the military. He came from signals, and we sent him to the Air Force and he did very well. He was in Air Force planning. You put people in there for their brains; you give people these kinds of jobs if they can't fly planes. He was very good there, then I brought him to direct joint ops, which Hsien Loong was doing. In all these jobs he did very well."

Going from the military to diplomacy

Choo would go on to become Singapore's Ambassador to Australia in the 1990s.

Choo audaciously brokered a deal with then-Foreign Minister S Jayakumar to not have to meet anyone at the Sydney international airport other than the President, Prime Minister and then-Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew ("not even him, the foreign minister!" he says with a laugh).

Australia was also the third destination he was offered to be ambassador for — he said no to London and Germany, because "the High Commission spends half their lives in airports receiving people from Singapore who think they are important enough to be met", but he joked to me, perhaps more-than-half-seriously, that "you don't say no three times".

He's gone on from then to hold non-resident ambassadorships to Fiji, South Africa, Papua New Guinea and now is our non-resident Ambassador to Israel.

Choo's view on other SAF scholar-Ministers

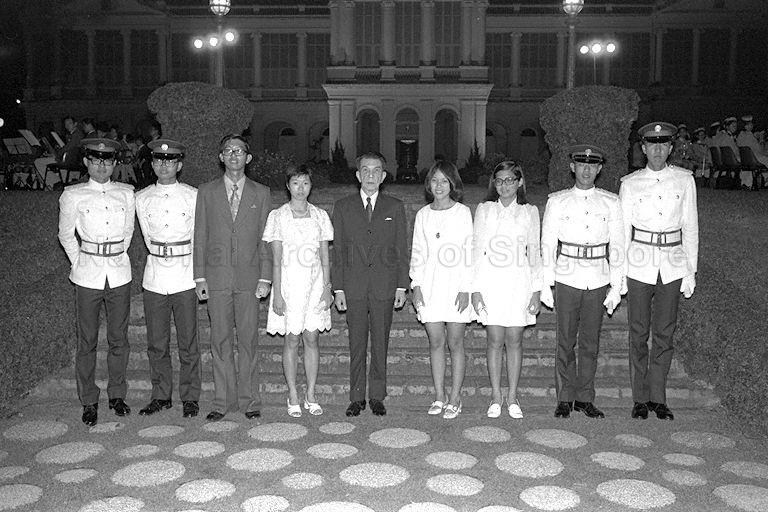

This amazing photo of President's Scholars from 1973 has Lim Hng Kiang (extreme left), Lee Wei Ling (girl on Benjamin Sheares's right), George Yeo and Teo Chee Hean (extreme right). (Photo via National Archives)

This amazing photo of President's Scholars from 1973 has Lim Hng Kiang (extreme left), Lee Wei Ling (girl on Benjamin Sheares's right), George Yeo and Teo Chee Hean (extreme right). (Photo via National Archives)

So who else was there?

Plenty. Choo touched on Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean, whom he praised as well, noting that he, too, directed operations in the armed forces before becoming Chief of Navy.

He tells me he interacted with all these budding future leaders as young soldiers as part of a panel of people who decided where the strengths of SAF scholars lay, and where to send them to.

They had two main classifiers, "command-oriented" and "staff-oriented", and there were some who were both, and others who were neither.

Lim Swee Say receiving the Public Administration (Gold) medal for his work at the EDB, from President Wee Kim Wee. (Photo via National Archives Online)

Lim Swee Say receiving the Public Administration (Gold) medal for his work at the EDB, from President Wee Kim Wee. (Photo via National Archives Online)

"So we try to rank them in this way, in order to decide where in the forces they should go. There are scholars who never went up the ranks in the military, but who are very good in their own right, like Lim Swee Say. Swee Say was a scholar in the army but he was good in other things, he went to EDB. And he was excellent in EDB.

Like Lim Hng Kiang... He was in the SAF but he was never given a chance to go up because he was nipped out very early into politics. Hng Kiang was Lieutenant-Colonel when he taken out into politics. So I wouldn't say he was staff-oriented or that he was not meant to lead, but he was taken out for politics before he could advance any higher.

...

Now, I'm not the only one doing this, of course, but I think in most cases we have been able to slot people rightly, and use them for their talent, their skill and their ability, and not waste a national asset. They (our scholars) are national assets. So if the SAF cannot make good use of them, we have to make sure they go to places where they are of better use."

Indeed, the proper general prefaced our discussion on his assessment of our political leaders as younglings with his take on them and their importance for our country, and indeed any large system.

"They are important assets you know, not only for the SAF but for the nation. You're taking the best brains in Singapore into the army, into the SAF.

And scholars, being what they are, always think the world of themselves — you can't help it; they are already there. So how you handle them, how you temper their expectations, is delicate and important; all things I had to learn."

When his scholars got asked to tea

George Yeo introduces Teo Chee Hean as a new candidate for the Marine Parade GRC by-election in 1992. (Photo via National Archives)

George Yeo introduces Teo Chee Hean as a new candidate for the Marine Parade GRC by-election in 1992. (Photo via National Archives)

Did Choo see some of these guys as future ministers and leaders of Singapore?

He again prefaces his response with qualifying that, of course, the decision of who goes into politics and who becomes a political leader is for "the party" to make, but certainly, he says, he "could see some of them" as leaders in the making, at that age.

"I won't say I was able to see that they were or they were not (potential leaders), but I would say that if given a chance, I could see some of them becoming leaders, yes. Some of them I would say never — not because they were not intelligent, but because they did not have political savviness and... you know, (he pauses thoughtfully) not being able to deal with people well enough."

But he is always informed by them, kind of shyly, whenever they are invited to tea.

"I mean you know, yes they tell me! Because they cannot suddenly disappear into politics tomorrow, you know...

But of course sometimes they do consult with me as well, as part of their considerations, some of them did come in and say to me, 'I'm not so sure I should do it'. So I used to tell them 'hey, you're doing national service in the army, and if you're going into politics it's also national service. So do your national service there. That's what I tell them.

Serving in Boys' Brigade with Chiam See Tong; talking to JBJ in Parliament; watching Sylvia Lim grow up

It is at this point that Choo qualifies that it is not the political party he is supportive of, but the service. And this is where I also learn that he goes way back with several key opposition figures in Singapore too.

Chiam See Tong, for instance, was Choo's senior at the Anglo-Chinese School, and they all (Chiam's brothers and family too) attended Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church together, and were in the Boys' Brigade and also ACS's swim team together.

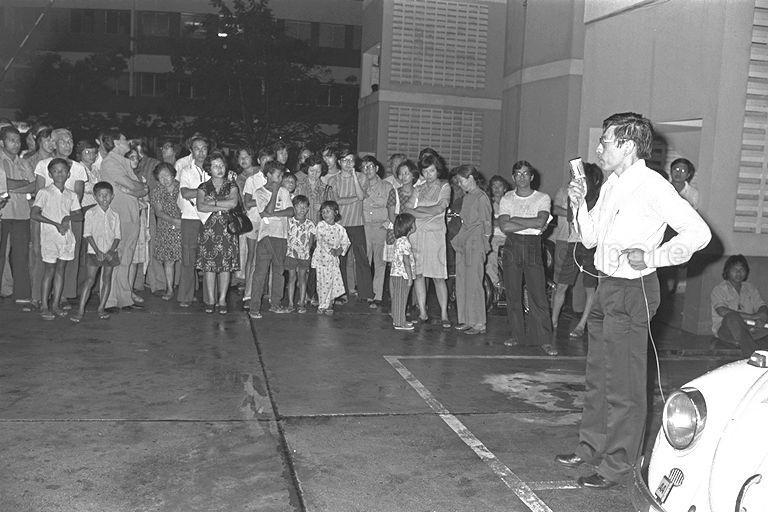

Chiam See Tong at an early election rally in the Cairnhill constituency in 1976. You can see him speaking into his megaphone, mounted on his Volkswagen Beetle. (Photo via National Archives Online)

Chiam See Tong at an early election rally in the Cairnhill constituency in 1976. You can see him speaking into his megaphone, mounted on his Volkswagen Beetle. (Photo via National Archives Online)

"See Tong was a regular Boys' Brigade person, a regular boy, a good sportsman, a good swimmer, I mean he was more a swimmer than anything else. And I never knew he would go into politics one day — there was nothing, there was no writing on the wall that he was that way inclined.

So when he first went into politics in his Volkswagen Beetle and his megaphone in Cairnhill, we all were surprised. But even up to the time he was Member of Parliament and I used to see him in the Istana, not when I was (Yusof Ishak's aide de camp) but when I was Chief of General Staff at the army at about the same time, for the opening of parliament and dress occasions, I would see See Tong and we would always talk.

And I have tremendous respect for See Tong, you know. I won't say we were in touch but whenever there was an opportunity we meet, we talk."

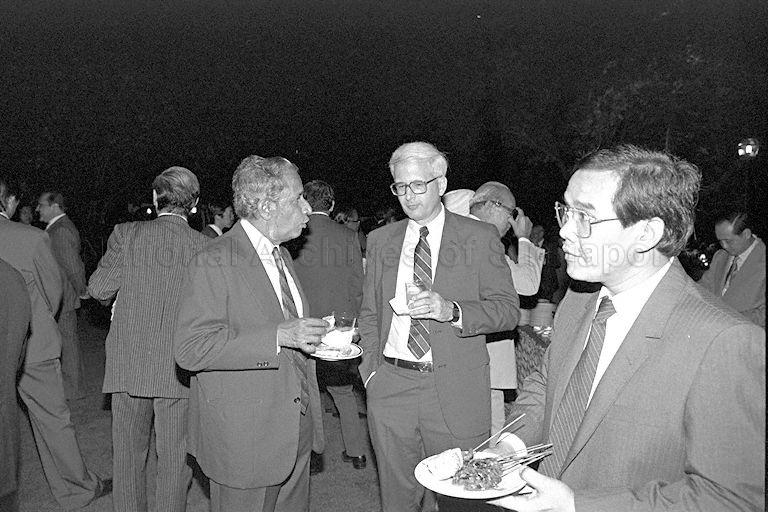

The late JBJ (on the left, whose side view we see here), who was then an MP for the Anson constituency, at an Istana reception. (Photo via National Archives Online)

The late JBJ (on the left, whose side view we see here), who was then an MP for the Anson constituency, at an Istana reception. (Photo via National Archives Online)

As Chief of Defence Force, Choo made it a point to go up to opposition politicians to talk to them. He has a story about Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam (JBJ) when Choo first went up to speak to him as an MP:

"I remember JBJ said to me, 'General Choo you dare talk to me ah?'

I said, 'why should I not talk to you?'

'You will be punished for talking to me', he said. I said 'why, you're not a leper!'"

Choo also remembers specifically seeking out JBJ when he attended his son Philip's military graduation as a cadet, and the late David Marshall, when he attended his son's events in the army.

"I used to make it a point not to avoid any of these people, because I said I am the CDF, I am army, I am military, I am not political.

And when Chiam See Tong was a member of parliament, he's a member of MY parliament. And it's the same for JBJ, David Marshall; even Low Thia Khiang, I talked to him as well."

Remembering Sylvia Lim's entry into politics

Choo also takes a moment to talk to me about Sylvia Lim, whom he knew as a young girl because of her father Lim Choon Mong, a police-officer-turned-military-officer-turned-lawyer (sounds like a kind of familiar path for her, doesn't it?).

"I actually remember the early stages when she came into politics because Choon Mong told me when he was still alive, he said 'eh Winston what's happening, my daughter is going into politics.' And I said 'good'.

'But she's going into opposition politics."

I said again, 'Good'.

So when I first met Sylvia she called me Uncle, I said, 'you're a member of parliament now, still call me uncle!'. But it was quite some time ago since I last met her.

Maybe that's why they never asked me to tea, you know. Because I always feel the military serves the country, the political head at the time. And he must be apolitical.

For a military to be healthy, for a military force to be healthy, they must behave like that."

Should generals be parachuted into top corporate roles?

Photo by Jane Stephanie

Photo by Jane Stephanie

I of course had to ask this question of Choo, who was cautious but ready to tackle it, as he had done so once or twice before.

Some examples of former Chiefs of Defence Force (CDFs) who went on to lead large and prominent companies in Singapore would come to mind: Ng Yat Chung at Neptune Orient Lines and now Singapore Press Holdings, for one, and also Desmond Kuek at SMRT, who handed over the reins to his successor CDF Neo Kian Hong.

"Whether military officers can or cannot do jobs, I think you cannot generalise. Even for a Chief of Army, for instance, you're in charge of 50,000 people you know. Looking after resources worth billions of dollars. Chief of Air Force, Chief of Navy, the same. Chief of Defence Force even more, all the three services are under you and the organisation, the people, the system is different.

But your ability to analyse problems and to find solutions to problems doesn't change. Whether it is in the military or outside the military, it's how you apply that knowledge and that experience from the military into whatever public sector that you go to that matters. I think this is where sometimes people don't do right, maybe. Not that they lack the ability, but maybe the application may not be right.

So to say that you see, high-ranking military officers do not make good CEOs in public companies and so on is not right. Honestly, you put the right man in the right place, he does the right job. So don't generalise generals."

Balancing the decision to perform national service & the outcome of facing public scrutiny if you fail

He does understand that people react the way they do when a former general takes the top spot at a large organisation and fails in the eyes of the public, but feels that they may also be expecting more than what is plausible.

"People don't like the idea that somebody who has done well in the military must also necessarily be given a job that is up there. But he is already there — you put him in the civil service ranking system and all that, he would be perm sec level. So what do you expect him to be?"

And to be fair, the avoidance of public scrutiny is also what led Choo to reject offers of entering the public service after he retired in 1992 ("I knew what I was good for, what things I could do, so it's best to find things to do my way").

He went on to Chartered Industries, where they made weapons for the army, and then into the foreign service, so as his staff size grew smaller and smaller, he learned that the leadership and management skills involved and applicable differed, especially because, as he says quite simply, "the way you handle civilians is very different from the way you handle soldiers".

"That is the thing that you must learn very quickly, how to switch — in the military you say something, things are done. Outside you have to sometimes — most of the time — persuade."

Photos courtesy of SMRT

Photos courtesy of SMRT

He said that he does sincerely believe that folks like Desmond Kuek and Neo Kian Hong went into SMRT believing they were called to continue their service to the country, and keen to do their best in that endeavour.

And he is certain Kuek, for one, did as much as he could, just as he knows Neo will do as much as he can from the experience both of them had in leading Singapore's mammoth defence force.

"So ultimately, it depends on what you make them do, and what you expect them to do within what period, and what the constraints that you give them are."

Why we need to spend so much money & time on defence

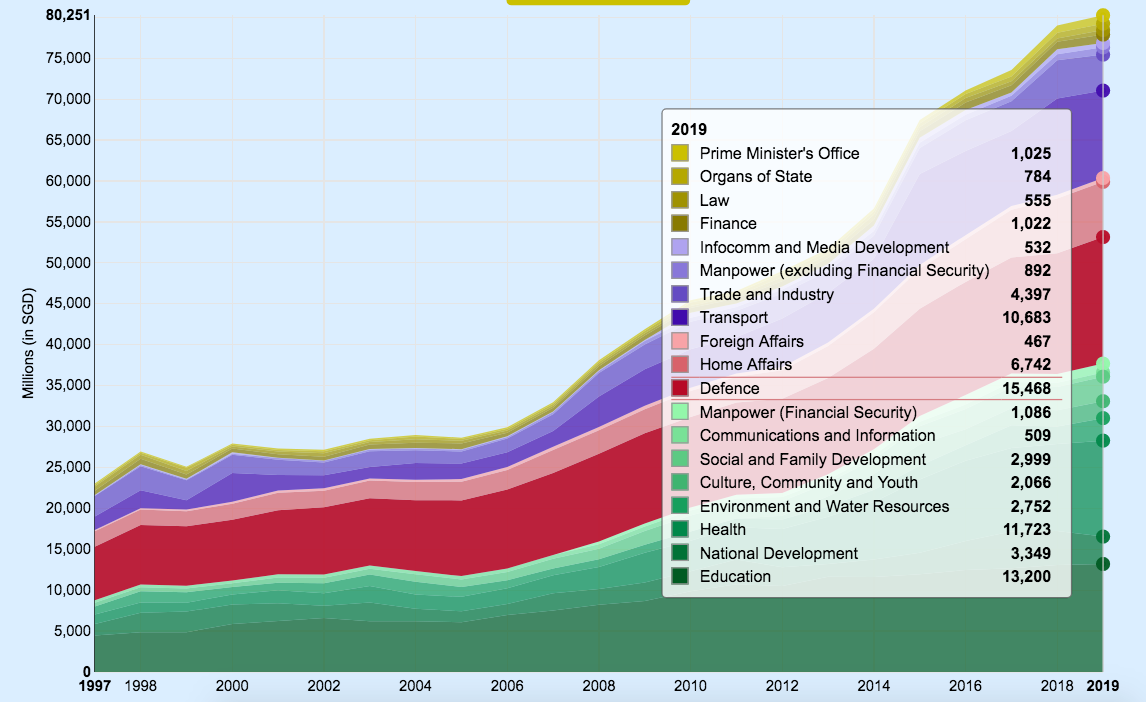

As someone who hasn't served National Service, I (probably not very intelligently) venture that it is sometimes tempting to wonder why our government pours so much of our annual national budget on defence — this year's, for reference:

Screenshot via viz.sg

Screenshot via viz.sg

And also parrot the complaint I used to hear from my friends serving NS full-time as well as in reservist that it can sometimes be a huge waste of manpower and time.

To explain this, Choo gives me a very lengthy and stern talking-to about how things were at the point of Singapore's independence — we had no air force, no navy, just one and a half battalions of soldiers.

"The number of Singapore soldiers we had back then was no more than 1,000. You defend what with 1,000? You go defend Takashimaya (Ngee Ann City)!"

And truth be told, he said as one of the SAF's leaders, he really felt "naked".

Naked in the sight of a tiny country with no natural resources, no hinterland (even Hong Kong had China), and threats all round — he reminds me that radical Malaysians were not happy with Tunku Abdul Rahman for what was in their minds "giving Singapore away", and wanted to "take us back", possibly by force.

A second big factor for him was the need for stability in the country — the only thing that would attract foreign investment to help our economy grow.

He went on to walk me through his thought process of how the army should be built — how big should it be? Can it be an all-regular army?

"But your system should support a population of at least 3 million, and cost much less than a regular army. And when you can mobilise citizens, you are involving citizens in the defence of the nation. Therefore it serves nationalism, social stability, and patriotism. That's why national service becomes a must, an institution for our survival."

Why girls shouldn't be conscripted for NS

He also explained how the length of NS has been reduced from three years to two and a half, and then two over the years, changes he says have been in response to the changing nature of our demography.

He even expounded on why, in his view, they don't take girls:

"It would be very salutary for morale to have girls fighting alongside you. But we cannot do it.

Now... the other reason that is often not mentioned but I'll tell you why — we have 100 per cent national service in the system. Everybody — sick, lazy, lame — comes into NS. So if we take in girls, every girl, we cannot be selective.

So we take in 25,000 men every year, we must take in 25,000 women. We don't have need for 25,000 women. We may need 5,000 to make up the numbers (to compensate our declining birth rates). But if you take 5,000, which 5,000 of the 25,000 women are you going to take? Then NS as a system fails because the moment you have selective NS, the moral stance of the system collapses. That's why we don't take women."

All this notwithstanding, the General stresses that he has great regard for women who serve in the forces as regulars — in fact as CDF, Choo is known by some to have almost always been staffed by female officers. ?

Choo also touches on food — a particular area of his interest and knowledge because he sits on the board of Foodfare catering — noting that incentives for companies like Foodfare rest on anonymous ratings submitted by soldiers.

He is aware of wastage, and says caterers do endeavour to minimise it, "to the extent of not making your soldiers go hungry".

We also talked about training safety. Choo concludes that while a lot of things have been done in the SAF to minimise training safety accidents, ultimately, it all depends on whether soldiers do what they are supposed to do, and avoid doing what they aren't supposed to.

"The best of systems you have is dependent on the last soldier you have on the ground. Whether he knows what he is supposed to do, he knows what he should not do but he chooses to do, you cannot stop that from happening."

A sobering way to conclude our conversation, perhaps, but also a good reminder, I suppose, of the necessity of a formidable defence force — what every Singaporean Son is part of.

Read Part One of General Winston Choo's story here.

Top photos via National Archives of Singapore Online

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.