Clement Chow does not believe in dressing his age.

"Why should we 'grow old'? Here, you mature," says the 59-year-old music veteran as he points to his head, "but don't lose the heart of feeling young all the time."

You may not recognise his face, or even his name off the bat if you're not old enough (hee), but you most definitely have heard his voice immortalised in the 1986 National Day song "Count On Me Singapore":

Incidentally, he will also be returning to the Padang tonight to perform another renditon of the well loved 1986 classic at the 2019 National Day Parade.

Chow is also the music programmer behind the Sentosa Musical Fountain, that put up light and sound shows for 25 years from 1982 to 2007.

And if you visit Takashimaya today, you might be able to hear its jingle (which has been playing for over 20 years) courtesy of Chow.

Dressed in a loud print T-shirt, a Hard Rock Café cap, and spectacularly ripped jeans, the multi-hyphenate entertainer is a marvellous ball of energy.

"I think the minute you slow down, you do," he says with a laugh.

And Chow has been keeping himself busy.

The man owns two production companies, Vertex Integrated Entertainment and Crazy Rich Entertainment LLP, but still finds the time to write, compose and record his own passion projects.

Just a couple of weeks ago, the producer-musician released a song called "None of This Came Easy" for Singapore's Bicentennial commemoration.

The soaring piece boasts the voices of Chow, Rahimah Rahim, Tay Kewei, and Nick Zavior supported by the 66-piece Bulgarian National Radio Orchestra. Its cinematically-shot video also features a multicultural fusion of local dancers, strung together by local hip-hop dancer and instructor Muhammad Zaihar:

And even more recently, Chow put out a remake of "Count On Me, Singapore", opening with him gently crooning a new preface before segueing into the song proper supported by a choir of Joo Chiat residents:

Both pieces, Chow says, are ground-up initiatives born out of his passion for music and his desire to contribute something for this milestone in Singapore's history.In fact, he lets on that "None of This Came Easy" was only conceived in February and after pitching it to the Singapore Bicentennial Office in April, Chow wrote, arranged, and recorded the entire piece by June.

"Don't get caught up in what you have to do, but get caught up in what you want to do."

This, Chow says, is a mantra he abides by — not that he has had any trouble doing what he loves.

The son of an accountant and kindergarten teacher, Chow had no lack of exposure to music growing up. Both his parents sang in the choir, and his father was also a huge vinyl record collector.

"He left me a collection of almost 700 vinyls and he loved it," says Chow. "From Glenn Miller to the Great Caruso and everybody in between. My house was always filled with the sounds of vinyl records being played."

Clement Chow was exposed to music since young. Image by Gareth Chew.

Clement Chow was exposed to music since young. Image by Gareth Chew.

However, it was in the Anglo-Chinese School in 1972 that Chow found his musical talent with the school's military band. Starting out as a fanboy of the school band, he followed them everywhere until the band conductor decided to recruit him.

The ACS military band consistently swept top honours at the annual Singapore Brass and Woodwind festival, so much so that Chow was noticed (and subsequently recruited) by the Singapore Armed Forces' Music and Drama Company (MDC).

The SAF MDC is known for churning out the biggest names in the entertainment industry today, from JJ Lin to Chua Enlai to Jeremy Monteiro. It was there that Chow honed his performing skills until his ORD in 1981.

One year later, Chow got together with three other MDC alumni — Tina Goh, Sheikh Tahir, and Roslee Harree — to form the Dissonant Affair, a singing quartet who transformed famous tunes with their complex harmonies and original arrangements.

The Dissonant Affair won the top prize in the 1982 Talentime by the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation with their rendition of The Beatles' "Got To Get You Into My Life" done in the funky style of Earth, Wind & Fire.

Chow's music career took off from there. From television to radio to live performances and sound production, the man was deep in the action of the roaring '80s music scene.

The roaring '80s

Chow's eyes brighten as he recalls the music scene in the 1980s.

"The 80s was the best! There was variety, you could go from club to club and you could find different types of music, different styles, you could never get bored!"

For a generation of people who is brought up on a diet of social media and Netflix, the idea of going out for entertainment can be quite foreign.

Entertainment in the 80s, says Chow, was going out for good food and then seeking a good band after. From country to R&B to pop, there was a good local band for every musical genre.

He rattles off a list of his favourite acts: Ramli Sarip, Alleycats, Black Dog Bone, Joe Chandran and The X-periments, Tania, and a band from the Neptune Theatre (from whom he learned to play the conga).

"We even had a wonderful band called The Flybaits at the Mandarin Hotel. They used to do impressions of various well-known pop stars and they were entertaining and funny!"

For Chow, the music scene of the 80s was the epitome of true entertainment. Image by Gareth Chew.

For Chow, the music scene of the 80s was the epitome of true entertainment. Image by Gareth Chew.

Entertainment was heady, wild, and imaginative.

Tania, says Chow, was the first band to use a microphone stand as a substitute for a bass drum — an innovative solution to space constraints in a small bar:

"There were no drums but the kick was amplified by making the sound louder, turning up the EQ of the bass, and the base of the microphone stand was the kick drum. He would kick it and that would sound like a kick drum."

Chow himself was a familiar face in the music scene.

Readers of a certain vintage might recall watching him sing and play at the Oberoi Imperial Hotel at Jalan Rumbia, Palm's Wine Bar at Holland Village, and the Changi Sailing Club, to name a few.

It was a scene that thrived on people's hunger for entertainment, which in turn afforded opportunities to homegrown musicians and performers.

Clubs were willing to shell out money — it was not uncommon for a band to pull in S$25,000 a month in the 80s — for good performers who could bring in and retain crowds.

So what changed?

Foreign talent, says Chow, which depressed the earnings of local bands. Then when it becomes too expensive to hire local bands, they eventually split up and try to find work as solo performers, often relegated to nightspots.

Social media, too, has pulled people away from the bars and the clubs and onto virtual spaces, and performers are forced to adapt to stay relevant.

"We've lived through these changes and we've seen it," he says. "The music community is very different today."

Musicians today lack connection

One grouse that Chow has about young musicians today is what he sees as an inability to connect with a live audience.

This situation is of particular concern for musicians in a Instagram/YouTube era who are used to performing in front of a camera.

"It's a scary thought for them because they're used to singing to a camera and that doesn't bother anybody. But when they're suddenly looking at a crowd, they're like, oh my God, there are real people out there."

"I've hired them before you and you will know them," he says with a grin, when we ask if he was referring to anyone in particular.

These, Chow says, are skilled, current acts that are "very good, socially on YouTube" and the way he sees it, they really know their stuff because they are willing to learn and they can pick up new techniques and approaches quickly from online.

"But with that knowledge you need to bring it out into your live performance and bring it over to the people," he says with a shrug.

Consummate musicians — like those Chow grew up listening to and worked with in the 1980s — know how to read their audience, connect with them and keep them entertained.

Admittedly it takes a certain kind of personality to hold the attention of a an audience but Chow insists that a lot of it takes practice, which you cannot get in front of camera at home.

"Whether you're an introvert or an extrovert, trust me, you can," he says emphatically. "I know of both types of personality who have been out there, who have been doing it well."

Musicians, Chow advises, need to have that "frame of discipline" to sharpen their performing skills. And one way to achieve that is to make mistakes.

"You want to keep making mistakes so you can be free," Chow adds. "It's okay to make mistakes, but it will be a big mistake if you don't pick yourself up after."

On National Day songs

Coming back to "Count on Me Singapore", Chow says he received the job to record it when he was working in a recording studio with Jeremy Monteiro:

"We were doing a lot of jingles then. So one day Jeremy said hey, national jingle, need you to sing it. So within an hour, we recorded it. I had no idea. It was just another job."

The next thing he knew, Chow was seeing himself on cinema screens and newspapers and was selling over 120,000 cassette tapes of "Count on Me Singapore".

It was a proud moment for Chow, from way back in 1986, and he considers it a privilege to sing a wildly-popular National Day song that still resonates today.

However, he is adamant that it is not about him.

"It's about a national message, being able to be counted upon, I think its a very universal message. Even Bruno Mars has a song on that," he quips.

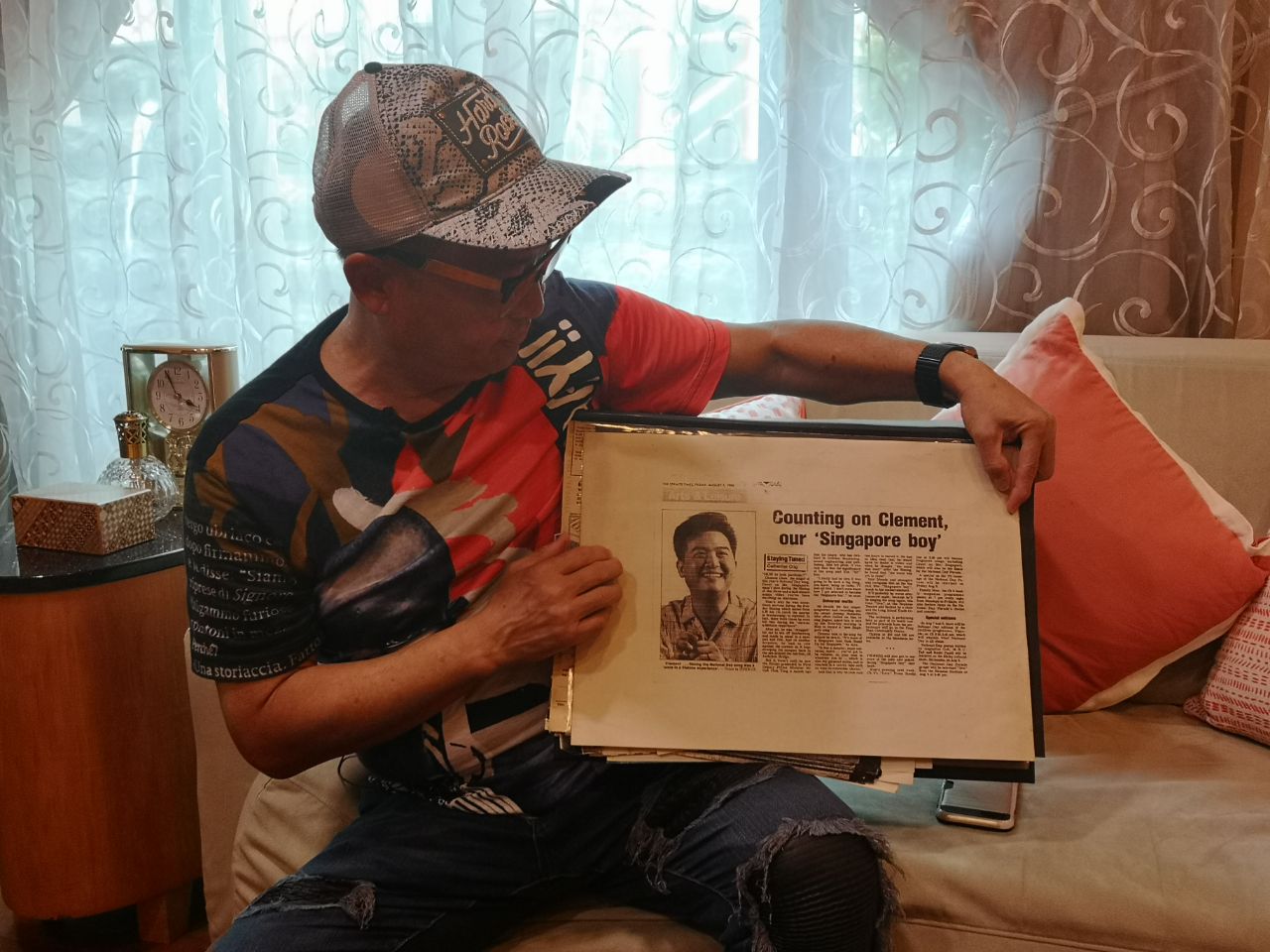

Chow posing with a newspaper clipping of him when 'Count on Me Singapore' was released. Image by Joshua Lee.

Chow posing with a newspaper clipping of him when 'Count on Me Singapore' was released. Image by Joshua Lee.

Speaking of National Day songs, Chow hesitates to pick a favourite because they all carry different messages.

Some, like "Stand Up for Singapore" and "Home" continue to resonate with Singaporeans for decades, but there are others that people don't sing anymore — songs like "It's the Little Things" and "Song for Singapore" — Chow thinks deserve more attention every now and then.

But it's hard to escape the fact that people are just not embracing newer National Day songs with the same fervour they reserve for "Home" and it seems we have given up trying to rouse hearts with a new number each year.

Last year's theme song was a remake of the 1987 classic "We Are Singapore". This year's song combines both the 2002 "We Will Get There" and the 2015 "Our Singapore".

Chow thinks it is the cost of trying to stay relevant:

"I've had very mixed reactions especially from your generation. They'll say cannot fit a circle into a square lah. In the old days an anthem is a communal song which includes people. Today, it's so cleverly done that it's hard to reach the guy who sells drinks on the streets or the aunty at the coffeeshop."

Newer songs, with their wordy stanzas and unfamiliar rhythms, can be very stylistically exclusive to certain groups of people.

Perhaps anthemic songs, conceived as a tool to cultivate solidarity among Singaporeans in the 1980s, have become outdated.

But Chow is not so sure.

"Yeah, I don't know. We haven't found the formula in the sense. What are you all looking for? What would stir you to say, 'Wow that's worth something, that's worth my attention'?"

"The government must ask themselves does [a National Day song] still work as a medium for messaging," he adds. "Is it effective? Are the people taking it in? Are the songs making them feel this way?"

Perhaps, he suggests, songs need time to grow in the hearts of their listeners.

"As a song rolls through time, it collects history, it collects stories so these things make it even more meaningful than when it first started," says Chow.

Case in point: When it was first launched, many Singaporeans thought "We Are Singapore" was “boring”, “uninspired”, and too “sentimental”. Today, it is hailed as a classic.

There's really no telling what the future holds for National Day songs.

As we wrap up the interview, I ask Chow about his thoughts on the Singapore sound. Singaporean culture, being so young and heterogenous, has not produced a sound that we can claim as our own, as opposed to, say, Indonesian music or K-pop.

For him, though, a Singaporean sound is simply about Singaporean experiences.

"Just be whatever your influence has been, and find your own style and just do it. Music is neutral. What makes it Singaporean or not is the person singing it."

Chow's quotes were edited for clarity. Top photo by Gareth Chew.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.