Every time there is an income inequality debate in Singapore, the name "Raffles Institution" will be brought up (see here, here and here).

But surprise, this phenomenon is not even new.

In fact, the issue of RI being a bastion of elitism has been around for some 130 years.

It first surfaced in the late 1880s.

Issue of elitism predates Singapore’s independence

In 1884, the Queen’s Scholarship — which is the predecessor to the current President’s Scholarship — was first introduced under the name of "Higher Scholarships in Singapore".

RI held the first examination of the Higher Scholarships that year.

A special class with the sole purpose of moulding suitable candidates for it was created within the school in 1885.

Given that this was the first opportunity for local children to study abroad and that few locals at that time could afford the costs of doing so, criticisms on how it fostered unhealthy competition among students and parents emerged.

The main gripe?

Scholarships for only some students concentrated a disproportionate amount of resources on a select few.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Clearly less egalitarian back then was the practice of having the scholarship limited to males only.

Scholarship revamped out of fear of biting colonial master back

The debate was shelved for a while, when the British authorities found that Western-educated elites in India ended up undermining the colonial hold on power when they returned from London.

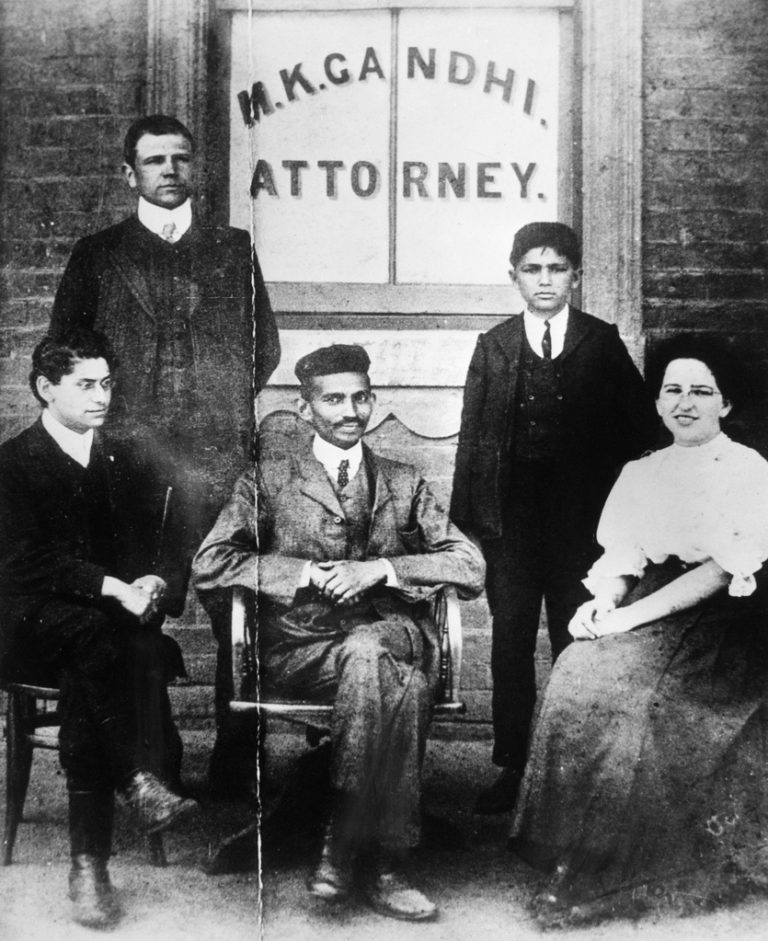

Gandhi as a lawyer in South Africa. Concerns of agitation by the educated colonised overrode the elitism debate. Via haveyouheardfromjohannesburg

Gandhi as a lawyer in South Africa. Concerns of agitation by the educated colonised overrode the elitism debate. Via haveyouheardfromjohannesburg

Fearing a repeat of the same situation in Singapore, the scholarship was suspended in 1911, but was resumed in 1924 as the Queen’s Scholarship.

This time, both genders were allowed to get the scholarship after much intense lobbying from the then Straits Chinese community.

A shadow cast by the intention behind its founding

This seemingly intractable problem of "Raffles Institution" and "elitism" can perhaps be attributed to the intention behind its founding.

According to the Raffles Archive & Museum Blog Page, Sir Stamford Raffles’ purpose in setting up the school was:

“Firstly... educate the sons of the higher order natives. Secondly, it was to afford the means of instruction in local languages to children of the East India Company. Thirdly, it was to collect the scattered literature and traditions of the country, so as to understand the laws and customs, with a view to helping the people.”

Essentially, RI was set up to help facilitate better governance of Singapore by giving locals the chance to “civilise” them in British ways, while simultaneously giving the colonial authorities better opportunities at “going native”.

It was also meant to serve as a kind of cultural capital in order to better equip the would-be members of the colonial government.

The discussion of establishing this institution on April 1, 1823, was even attended by both Sultan Hussein Mohammad (still Sultan of both Johor and Singapore at that point) and Temenggong Abdul Rahman (the Malay noble responsible for maintaining law and order), underscoring the importance that all sides placed on this endeavour.

All three figures personally contributed to the funding of the school with Raffles forking out $2,000 and the Sultan and Malay noble forking out $1,000 each.

Colonial legacy holds strong

If the colonial intention behind the school was to send local Singaporeans overseas to the United Kingdom, it is safe to say that Raffles succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

According to the UK’s Varsity, RI is one of the top five schools in the world that contributes the greatest number of students to Oxford and Cambridge for the past 11 years, up till 2017.

University of Cambridge Facebook

University of Cambridge Facebook

Additionally, according to the global education consulting company, Crimson Education, “Raffles also boasts one of the highest Ivy League admissions rates” -- so much so that at one point, the Wall Street Journal ran a feature article on it with the title, “Gateway to the Ivy League”.

(Full article found here on mrbrown’s blog.)

Yale University

Yale University

Obviously, the school no longer helps British people “go native” in Singapore to better rule over them.

And whether the school can be called a cultural capital in the sense that it is meant to reflect the various cultures of Singapore, is also debatable.

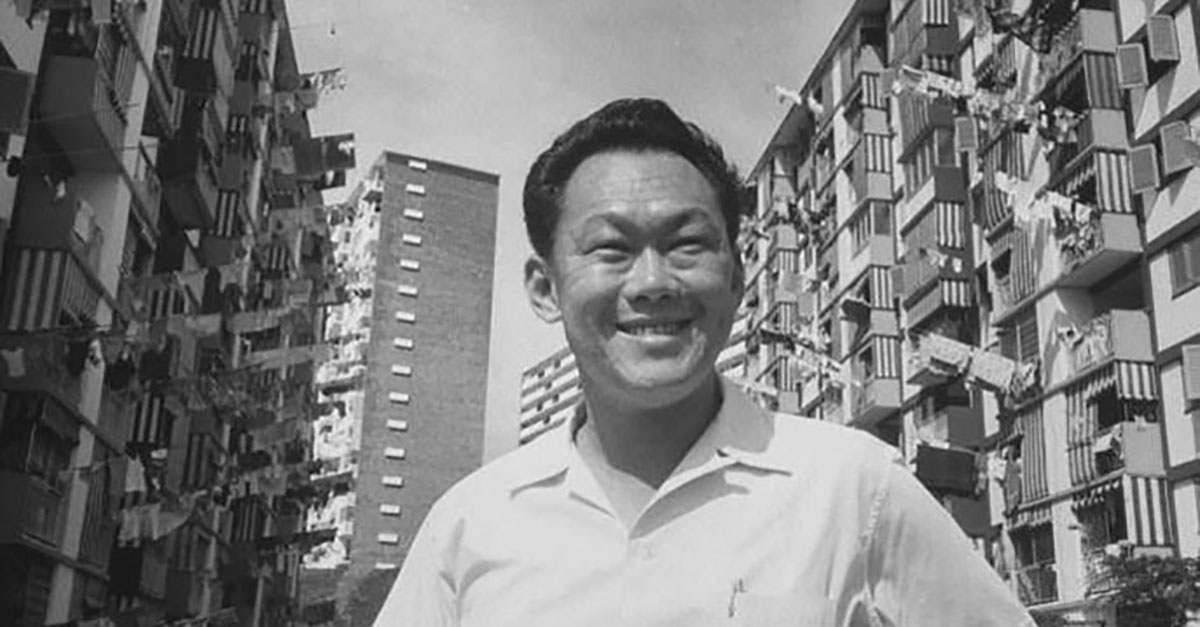

However, one cannot deny that the intention of producing people to aid the governing of Singapore has succeeded tremendously.

Yale University

Yale University

Apart from Lee Kuan Yew, other prominent people in the government from RI include:

- Peter Ong – Former Head of Civil Service

- Edwin Tong – Senior Minister of State for Law and Health

- Tan Chuan-Jin – Current Speaker of the Parliament

- Ong Ye Kung – Current Minister for Education

- Chan Chun Sing – Current Minister for Trade and Industry

- Lim Hng Kiang – Former Minister for Trade and Industry

- K Shanmugam Sc – Current Minister for Home Affairs and Law

- Goh Chok Tong – Emeritus Senior Minister

At this point, depending on your perspective, the word “elite” will no doubt be coming into even sharper focus in one’s mind along with all the baggage it bears -- baggage that we should note, has been around for over 130 years.

Debate today

With the debate raging around inequality, meritocracy and elitism these days, what is significant is that the core essence of the debate has pretty much remained unchanged: The concentration of resources for a chosen few and the kiasu mentality it breeds.

Only the framing of the problem has shifted, from being about colonialism and sexism, to one about inequality and unequal access.

Perhaps, we can do better than the British in tackling this.

Related story:

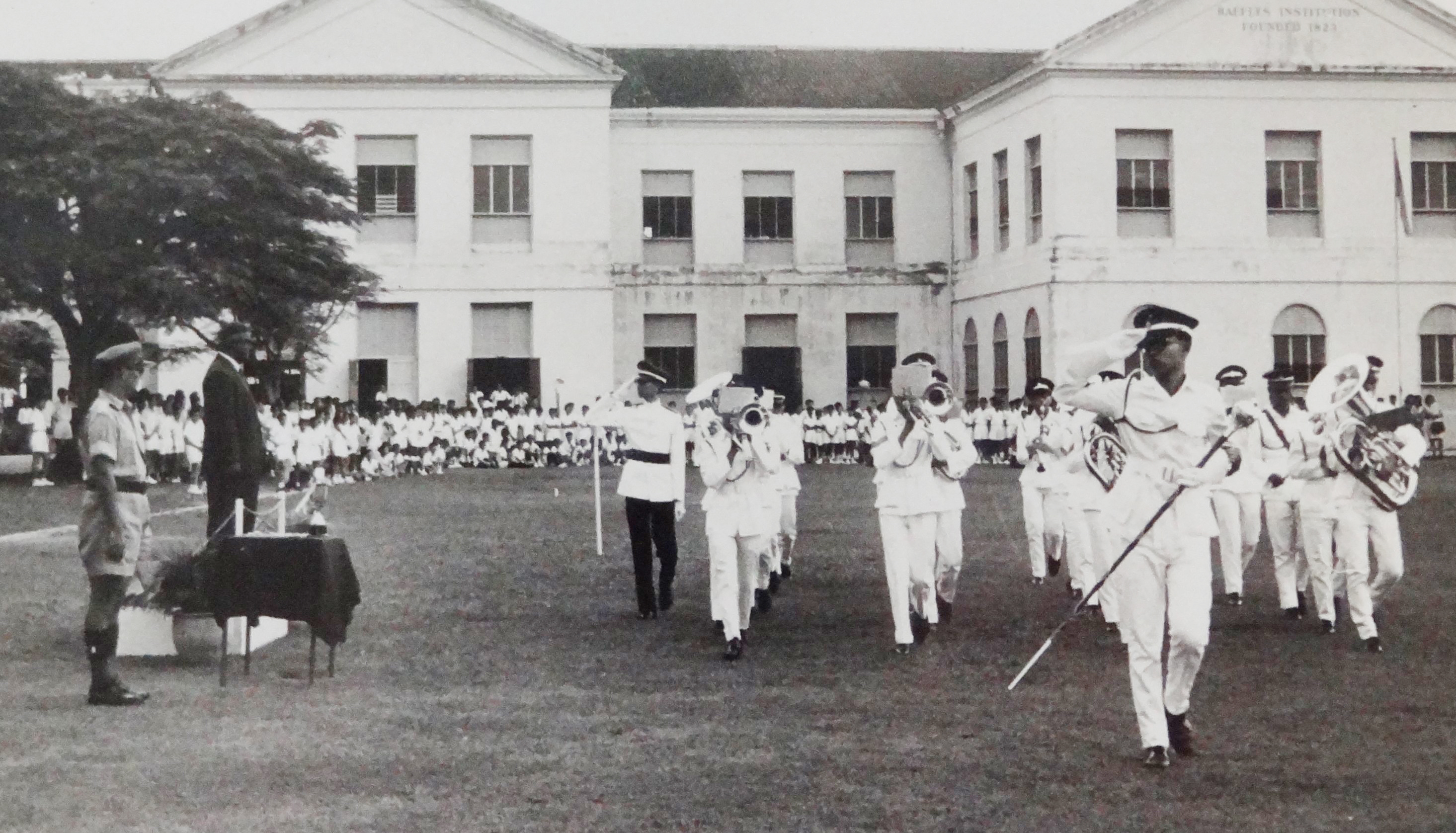

Top photo by Raffles Institution

#SG200 is not a celebration. It's a commemoration. What's the difference? Click the logo. Maybe these articles might help.

#SG200 is not a celebration. It's a commemoration. What's the difference? Click the logo. Maybe these articles might help.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.