Yes, corruption did happen in the Singapore newsrooms of the 1970s.

Committed, no less, by Singaporean veteran newspaper editor PN Balji himself.

In his early years as a rookie crime reporter at New Nation, a now-defunct local English-language newspaper, he and his colleague were up against fierce competition from the also-now-extinct Singapore Herald, whose chief reporter, he learned, was bribing the firemen who answered the media phone lines for scoops and exclusives on incidents that happened.

Balji tells us he felt compelled to as well, and soon, both him and former police inspector Wee Beng Huat were paying up for their pick of the litter. But of course, he was eventually rounded up by officers from the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) — an irony considering just two or three years prior, he almost landed a job among their ranks as a special investigator (he chose the Straits Times Press over them, though, because they got back to him earlier).

"I was picked up by CPIB officers, interrogated for 10, 11, 12 hours... We were fined. We were charged, we were convicted, the firemen were charged. But when I talk about it I feel really bad because the firemen got sacked. That... yeah. I didn't lose my job, but they lost theirs."

He cheekily, perhaps ruefully too, adds that his counterparts at the Singapore Herald were never caught, however.

"Because I mean we have to get the stories, right, although we knew it was against the law. If not the Singapore Herald will get all the scoops. But they didn't get caught. They were smarter than me. Because the person who was the chief crime reporter was a guy called Harold Soh. He was an ex-policeman so he knew how to get around it."

One of his first lessons in life: that it isn't always fair.

His company would go on to pay the fine, and he was shifted to a sub-editing position — which, interestingly, set him on a career path he would end up deriving immense satisfaction from over the next four decades.

A decade at the helm of The New Paper

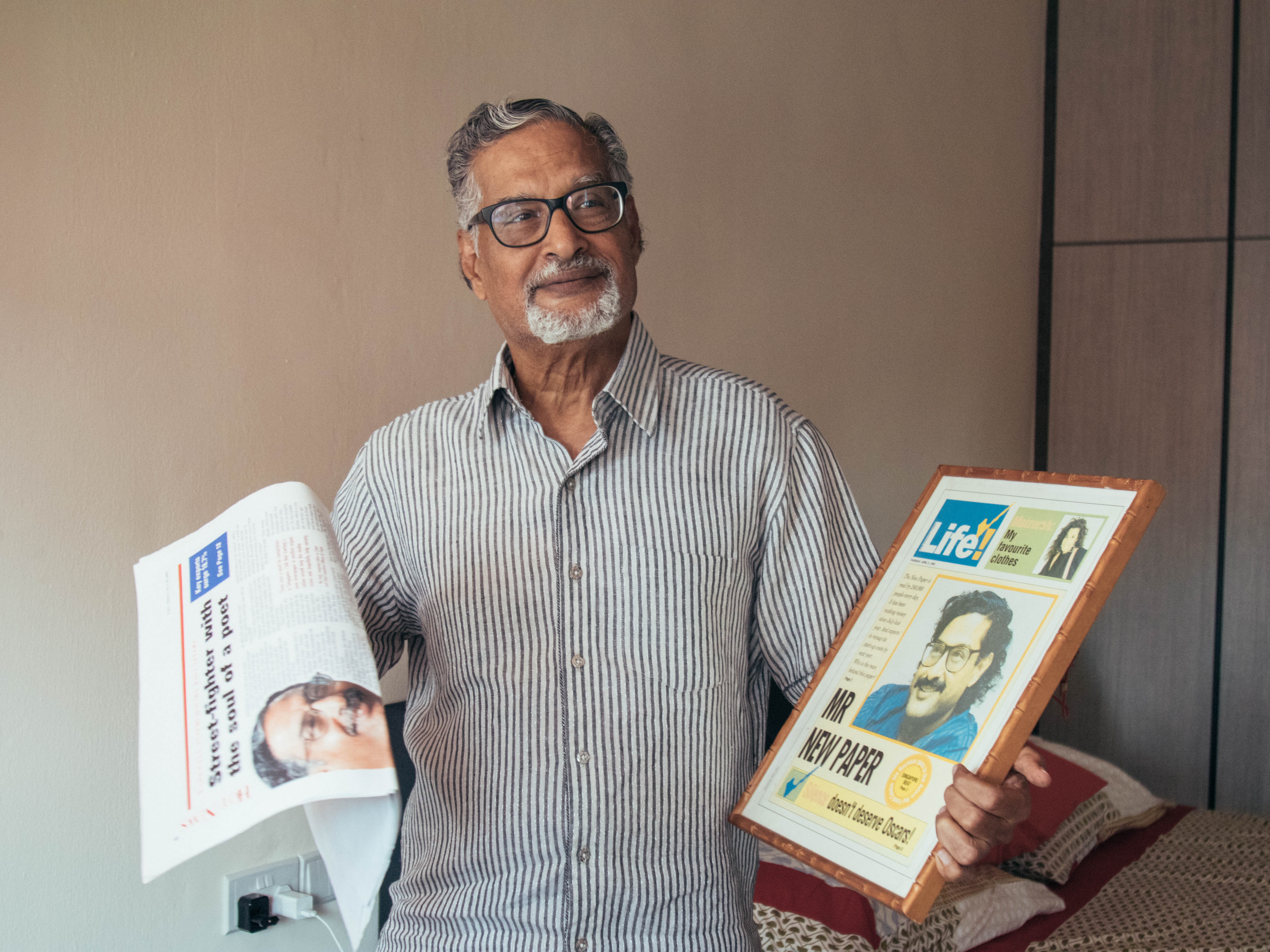

An interview with Balji on The Straits Times when he took the helm of TNP. Photo by Andrew Koay

An interview with Balji on The Straits Times when he took the helm of TNP. Photo by Andrew Koay

This framed and blown-up interview published in The Straits Times in April 1992 hangs on a wall in Balji's two-storey home in Bishan — a home, he stresses, not a house, that he and his wife Uma have lived in for the past "40-plus" years and only renovated in a major way once, recently.

It's there alongside photographs of 69-year-old Balji's family — he has two daughters, both of whom are married now, and he is cheekily proud to display a large framed poem written by one of his two grandsons that hints a preference for Grandma and Grandpa's house right outside his kitchen.

And certainly, having done time at The Straits Times and being the founding editor-in-chief and CEO of the TODAY newspaper, it is Balji's decade at the helm of The New Paper (TNP) that he has the most to talk about, and is also the subject of many a fascinating story; the centre of his career's highest highs and lowest lows.

The highs included successfully pulling the struggling two-year-old tabloid newspaper out of the red, overseeing many scoops and taking many bold risks in deciding on lead stories and headlines, in a time before social media was able to equalise the playing field between long-cushioned mainstream newspapers' bottom lines and smaller, nimbler and all-online players.

This was a time, one should bear in mind, when the only ways to get news were through reading the newspapers, and perhaps listening to the radio or watching the half-hour segment on Channel 5 at 9:30pm.

What do you do when a newspaper lives and dies by its front page?

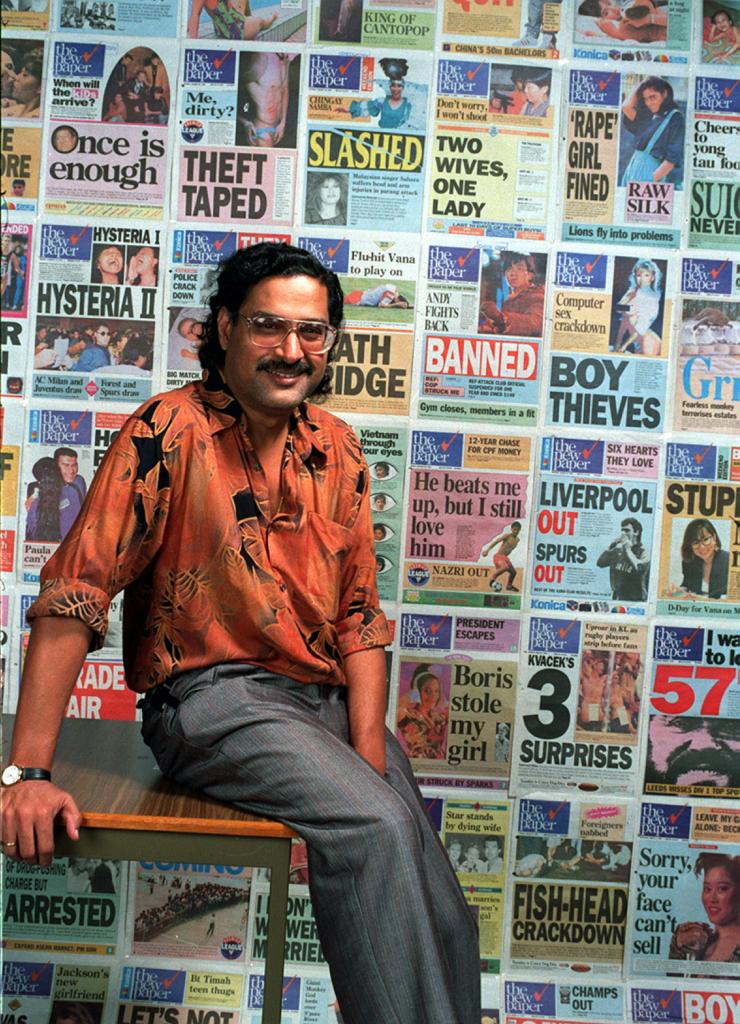

All the epic TNP front pages. And yes, that's Balji in the heydays. Photo courtesy of PN Balji

All the epic TNP front pages. And yes, that's Balji in the heydays. Photo courtesy of PN Balji

Settling down into the sofas in his living room, decorative touches "all specially selected by Uma, I had nothing to do with it", Balji shared many of his personal experiences with SPH, which at the time was located at Times House (which no longer exists) on Kim Seng Road.

My favourites, though, were how he made The New Paper truly sellable to the man on the street through what he calls (for want of a better term, he says) a "democratic system" — by getting various non-journalism-trained members of the paper's staff to make decisions on its most important page: the one right in front, better known as Page 1.

He said he would get, say, an artist, to choose the Page 1 story and come up with a headline, and each day's finalised Page 1 would be cleared with the paper's office girl named Mala.

Mala's task: to look at it and let all the editors seated at the big desk finalising the newspaper's pages for print whether or not she could understand it. If she couldn't, it would be sent back to the drawing board.

Balji would also fax a copy of the paper's front page to SPH's circulation department to ask them if it would sell or not. He would get a response from them based on a gut feel, which he would also heed and act upon carefully.

"Because they know the pulse. And I had built up such a good relationship (with them) and we became very close that they will tell me in my face if this page 1 will work or not. And they will tell me, 'this one won't work'.

And I will never ask for the reasons. Because if you go to the circulation department people and ask for reasons, the next time they will never come to you. They're just giving you a gut feel. Don't try to get an intellectual reasoning behind it."

He recounts also how he was very moved by encounters with newspaper vendors, who he also took the effort to befriend over the years.

One of these, he recalls, refused to take his payment for a copy of The New Paper when he was on his day off and at a coffee shop in Serangoon with unkempt hair, shorts and a torn T-shirt.

"There was this random passerby, I don't know him, so I just went and stopped him to buy a copy of The New Paper so I gave him the money. He said no no no I don't want. I said why, he said how can I take money from the editor of The New Paper?"

Another vendor on Battery Road whom Balji did know very well and went to see from time to time refused payment for a copy of the Financial Times, which was valued at a hefty S$6.

And the cool thing is, Balji continues to maintain these relationships today.

And there are also his biggest regrets

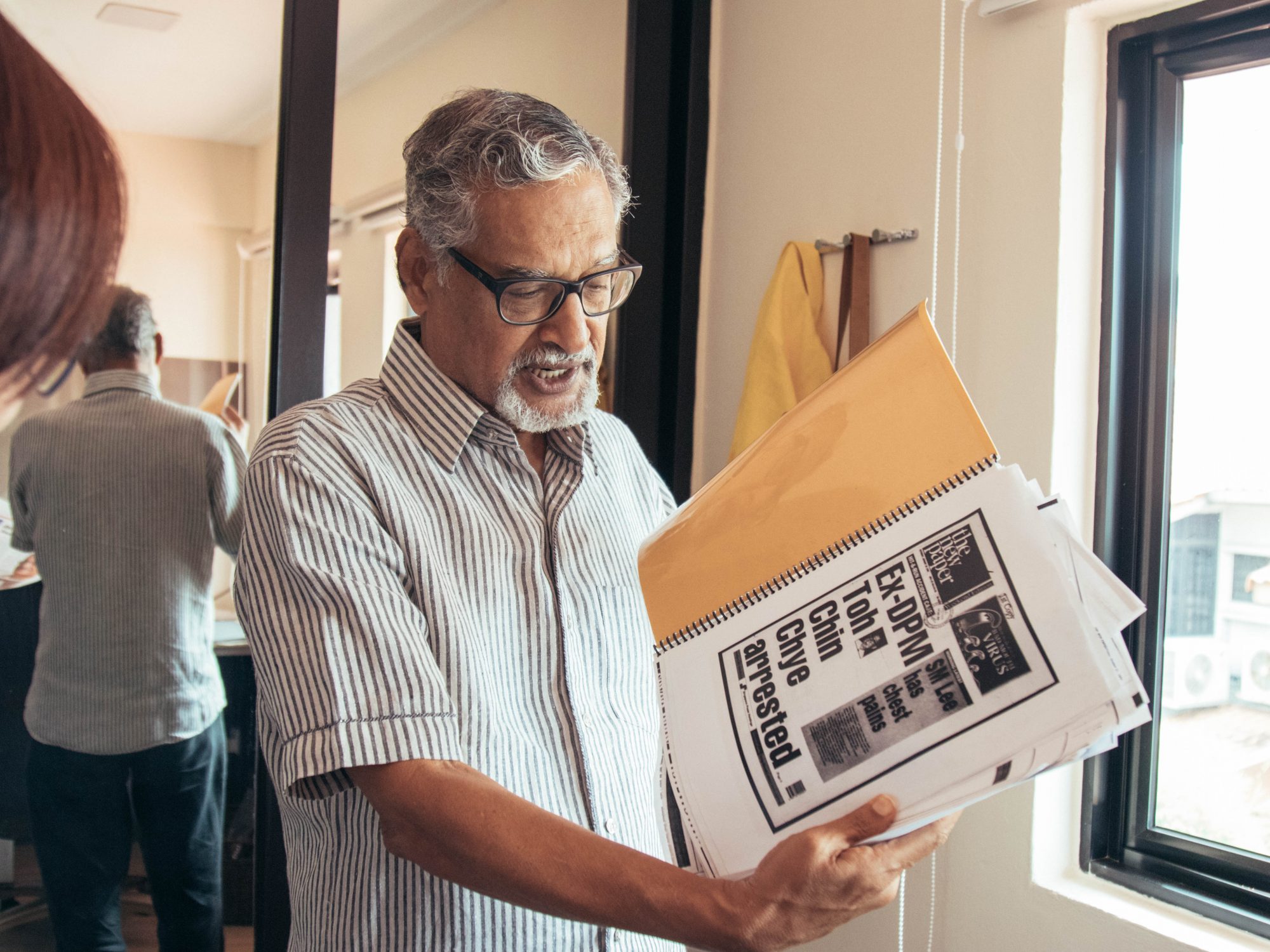

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

What Balji's showing us is the front page that undoubtedly brought him the most regret as TNP's editor: what he calls the Toh Chin Chye affair — an epic case of unintentional fake news of the print media era.

In short, it was when a talented reporter skilled with scoring scoops from reliable police sources was too trusting of one of them just once: a drunk driver of a red pickup van was involved in an accident, found parked at an HDB block, and was arrested, and he was misidentified as the late former Deputy Prime Minister who shared the same name as him.

It somehow bypassed the multiple levels of checks that exist at our mainstream newspapers:

- it wasn't in the schedule of stories that is always forwarded to the paper's editor-in-chief (at the time, Cheong Yip Seng), out of fear that another paper, chiefly The Straits Times, would pick up on their scoop;

- the sunrise editor who saw it raised suspicions but was thrown off by a coincidental call from the Prime Minister's Office alerting them to an incoming press release — it turned out to be about the late Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) being admitted to hospital and completely unrelated to Toh Chin Chye, but he assumed it was and that call confirmed his expectation that the story was true; and

- everyone was diverted to focus on the LKY being admitted to hospital story and promptly forgot about the Toh Chin Chye story.

Oh, and as fate would have it, Balji himself happened to be away at the time, on pilgrimage in India.

He relates this story in a full chapter of Reluctant Editor, a book he's written about some of his key experiences as a newsman, explaining he feels the need to do so partly because he "needed to get it out of (his) system too".

"You have to know that there are newsroom procedures you cannot subvert, you must follow. And what happened... this was a tragedy. this was a real calamity...

And it's a very sad story. The reporter had to be sacked, the two editors demoted, but there was a positive side to this story... they all went on to do very well."

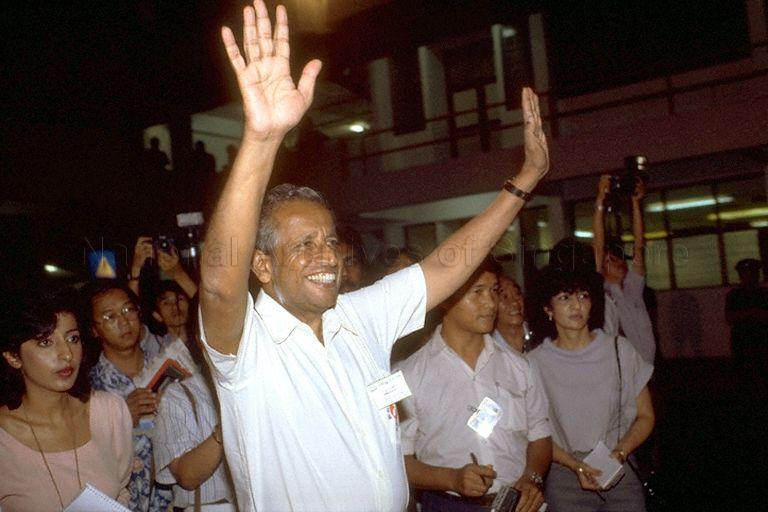

Photo via National Archives of Singapore Online

Photo via National Archives of Singapore Online

Unfortunately, he unwittingly played a role in causing aggravated defamation damages for the late Workers' Party (WP) chief Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam (JBJ) when, on Polling Day of the 1997 General Election, due to unexplained circumstances some police reports filed by fellow WP candidate and hotshot polyglot lawyer Tang Liang Hong appeared in TNP's fax machine one morning, free for reproduction and publication.

The content of these reports was deemed defamatory by the People's Action Party leaders who were named, including former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, and they subsequently successfully sued JBJ and Tang for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

(His deputy, Bertha Henson, recently reflected on this episode as well in this blog post.)

It was, if there ever was any, a time for Balji to truly appreciate the impact of the work he was doing. But it also gave him the chance to dwell on the nature of dissent in Singapore and how it is done.

"I do (feel sympathy for JBJ) up to a point, but I thought he played his game wrongly. He was a bulldozer without brakes. If you want to succeed in Singapore, you have to be a bit... you can still be opposition, you can still be critical of government, but you cannot just go, you know.

Look at Low Thia Khiang, look at Chiam See Tong, I think they succeeded (in opposing the government) and it was good for Singapore eventually. But I thought he (JBJ) was an extremely brave man, he sacrificed his whole life for an uncertain cause."

Walking the tightrope on the edge of Singapore's constantly-shifting "OB markers"

Which brings us to his own style of journalistic dissent.

How is it that when other top newspaper editors faced professional consequences for rebuffing government action or demands at various points, Balji was somehow always able to escape more or less unscathed through his own career?

It's likely if you've been here awhile and follow the news, you will have heard of the term "OB (out of bounds) markers", a term used to refer to things the government is not willing to tolerate you writing about — and if you do, various types of untoward consequences may follow.

For Balji, his time in the news media was characterised not as much by staying safely within the boundaries, but "walking a tightrope" on their edges, and whenever possible, making attempts at the edges of Singapore's existing OB markers.

"I think it would be a brinkmanship. It's like walking the tightrope and knowing when to strike, when not to strike, which are the real no-no-no issues, some of the grey areas, and these are the grey areas you really can push it a bit.

Nobody knows where the OB markers are. Even the government — I mean of course there are some, language, religion and all that. But other than that, as society develops and progresses, the OB markers will naturally change. But nobody will tell you.

So how do you know? You have to test. Test. If no reaction, that means the OB marker on this subject has moved. But depends on how many people try.

But again, I think that if I were in The Straits Times, I may not have been able to do that. Because The Straits Times is seen differently — the government always looks at ST very closely because for them it is a very important vehicle."

The gay headline

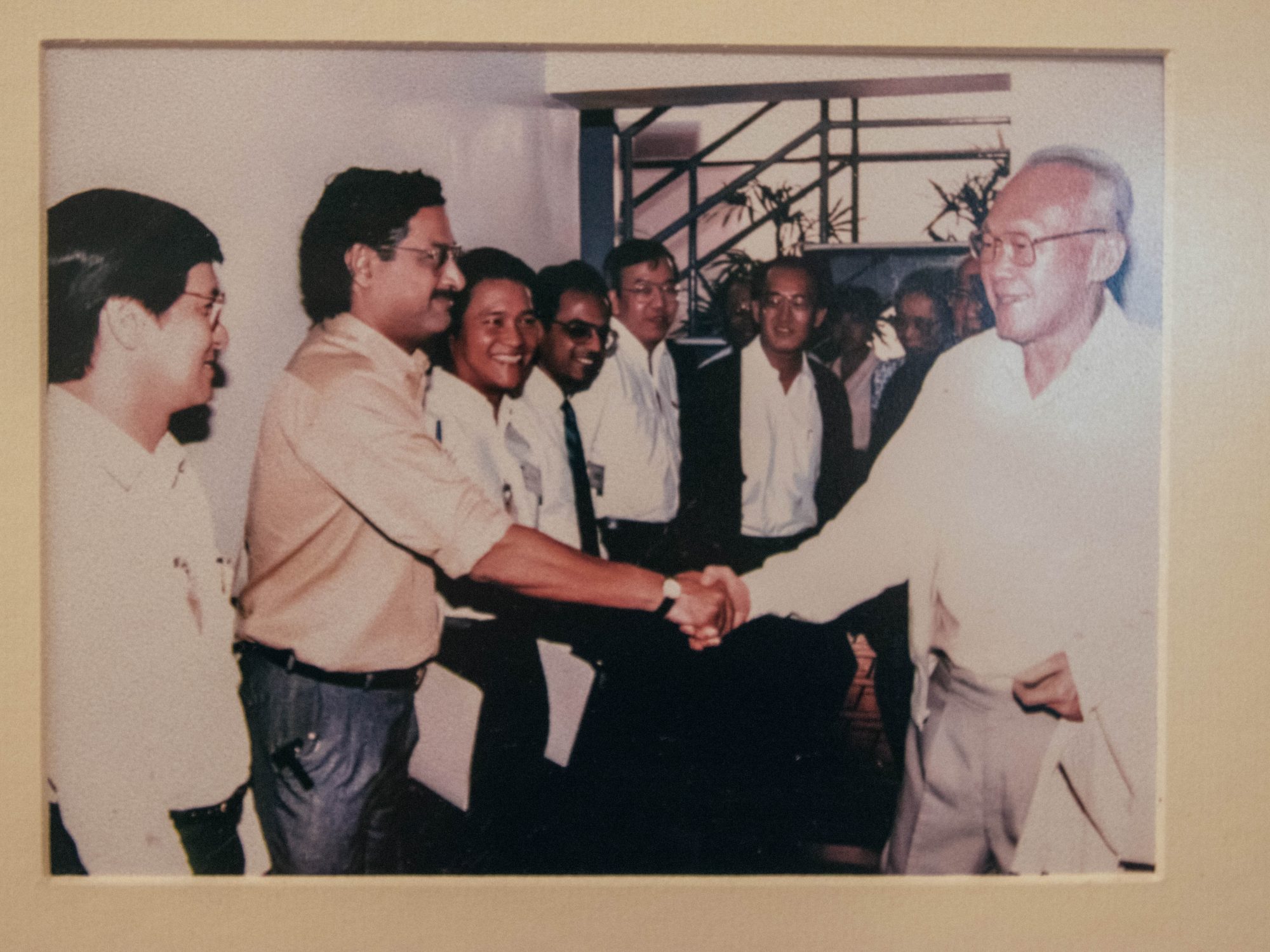

A picture of Balji meeting the late LKY on a wall in his house. Photo of this photo by Andrew Koay

A picture of Balji meeting the late LKY on a wall in his house. Photo of this photo by Andrew Koay

He relates one particularly proud moment where he did this — it involved coverage of one of the first public comments by the late LKY on gays.

It was December 11, 1998, and LKY was on a live CNN news show answering phone calls from viewers. Balji recalls that the first call was from a man who said he was gay and living in Singapore, and asked point blank if there was a future for gays in Singapore.

"And you could see LKY was a bit uncomfortable, but he recovered very fast, and he gave a damn good answer. He said if society wants gays, the government will allow. Which I thought, of course you can argue against that point and say the government must set the standard right? But he still had an answer for it.

And I was very sure that the Straits Times... would not pick up that angle. That was when self-censorship was happening. But I felt this was a very very important point that Mr Lee has made, and so I decided to use that angle as a page 1 story. Not the lead, but as a page 1 story. And the headline was, I think, he was senior minister at the time: SM, I'm gay. What is your stand on gays? Or, SM, what is your stand on gays? Something like that."

Why'd he do it, despite concerns expressed by his subordinates?

Balji cites two reasons, 1) it is in the public domain, and 2) it was the first time he had heard the government actually articulate its stance on gays. And that was that, and they didn't get into any trouble for it.

"We don't want to stir up the hornet's nest again" Govt on ministerial salaries

And where there were times he pushed the boundaries, there were others where he caved to pressure, deciding not to strike.

Sometime in his three years as the founding editor-in-chief of TODAY, Balji recalls that he received a call from ambassador-at-large Ong Keng Yong, who was at the time press secretary to then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong.

"So he called with specific instructions to say that we are telling all the media, we don't want you to highlight the salary. Every year there will be a kind of a revision, you know, of the salaries; we don't want you to continue to harp on it and mention that so and so got so much, and salaries went up by so much. Because you know, as far as we are concerned the matter has been discussed in great detail; we don't want to stir up the hornet's nest again.

And one part of me said this is news, we have to report; another part of me said I can see the reason, and I'll let it go. So I went with the latter.

Was that the right decision? If today I was asked to do it, I won't do it. I would have fought against it, and tried to get it out somehow — you know, in a way that will not get them too angry."

Continuing to push boundaries in the Singapore media space today

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

One thing Balji wants to make clear is that he is doing his part, despite his personal view that there aren't enough people in journalism today who are trying to push the boundaries, and to continue experimenting with and exploring Singapore's OB markers.

In The Straits Times, for instance, Balji believes that the lack of meaningful analysis he perceives that is coming from them boils down to the fact that it has lost some of its best higher-level editors, which he calls "number 2s and number 3s and number 4s".

These, he argues, are best placed to challenge the politically-influenced editorial calls of the editor-in-chief, for instance, and try to re-edit stories to make them publishable or train younger journalists to become better, more rigorous and critical reporters.

He mentions the likes of former deputy editors Zuraidah Ibrahim and Alan John, as well as former news editor and China bureau chief Peh Shing Huei, as solidly talented editors who had left in recent years as examples.

What about TODAY and CNA? Balji says he feels they latch onto stories faster, and he detects "a certain hunger" that shows they are braver in their analysis and angling.

Feeling the impact of speaking out... in press retirement

It's funny, though, that after a peaceful professional newspaper career, Balji would find himself experiencing political repercussions for his writing only in the past decade, which he has spent, among other things, contributing commentaries freelance to various online publications.

He notes how in 2011, after he remarked in a Yahoo op-ed the uneven coverage of then-presidential candidate Tony Tan at random events, he found that his Asia Journalism Fellowship contract was not renewed by the Temasek Foundation despite it having been renewed easily on multiple occasions prior.

He also confides that he now faces an odd "do-not-feature" ban with Mediacorp and its news media, with CNA no longer inviting him onto their news programmes, and journalists from TODAY seeking comments from him and not running any of the quotes he gave them.

"The most recent example was some time ago when this reporter approached me and I told her, if you can give me an assurance that my comments will be used, provided you consider them to be okay, then I will respond to you. She never came back."

News sites that came and went

Logos via IQ and Six-Six News

Logos via IQ and Six-Six News

Balji also experienced a similar incident with the now-defunct news website Six-Six News, run by former newsman Kannan Chandran. He had written a commentary on the Hepatitis C outbreak at Singapore General Hospital, questioning the delayed announcements and communication, and soon after was taken to lunch at Raffles Hotel by Kannan.

"He told me 'I've got to ask you to stop writing'. So I said why? 'Because the financier of this project told me that you shouldn't write anymore'. I don’t believe that he himself decided."

The site would eventually close, alongside Viswa Sadasivan's Inconvenient Questions, conveniently after the last General Election.

We had to ask Balji about The Independent Singapore (TISG) though, a controversial alternative news site that has made prominent reporting errors in the past, and why he is associated with the company as a shareholder and not an editor.

He tells us another story:

"I was not supposed to be the editor, I was only supposed to be the consulting editor... then a couple of months before launch, I got a call from a person who is well-connected. He invited me for breakfast — and when this kind of people call me for breakfast, I know it's not a good sign. And he said that so-and-so told him to tell me, and this guy is quite high up in government, not to be associated with The Independent.

So I got very upset. So I said you go and tell him that (so it's not a her) now I will become Editor! ... so yeah. And then after that there were a couple of people on the verge of giving us money who withdrew."

He also explains that he started out actively involved in the site's operations, but eventually had to step back, saying he lacked the stamina. But he says he still makes himself available to answer calls and give advice when it's needed.

And also he continues to keep shares with the company because he's serious about supporting the media landscape. He also praises the columns written by veteran Straits Times journalist Tan Bah Bah, and says he hopes TISG can bring on more writers like him.

"I am looking at it as a long-term kind of thing. I am a believer in media competition and I do see some potential in the product."

So, what's the moral to all these stories?

Our takeaway is that Balji has done his best in the Singapore press environment, and is continuing to try to do his part in the best ways he knows how — even culminating in a book he has written, Reluctant Editor, which will be launched on Friday, June 14 (you can attend it and buy a copy, details here).

He says he is inspired by veteran editor-in-chief Cheong, and hopes to create and continue a trend of bucking the norm of journalists bringing their stories to their graves.

"There are so many stories (in journalism in Singapore), and I also want to show (readers of my book) that your understanding of the media, what you think of the editors, might be absolutely wrong.

We have this band of editors who would push — succeed sometimes, fail sometimes, but they did that."

Top photo by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.