For someone who carries the nickname "Flying Fish", Ang Peng Siong is surprisingly measured and contemplative.

Meeting him one April morning at the Singapore Island Country Club, I can see why someone once described him as a "gentle giant".

Ang cuts a tall, imposing figure that is quite at odds with his mellow, bordering shy demeanour.

The 56-year-old definitely does not outwardly display any hint of the explosive energy that made him the world's fastest swimmer in 1982.

The world's fastest swimmer

Readers of a certain vintage will recognise Ang's name and face.

After all, he was one of Singapore's prime swimming champions in the 1980s.

Ang first represented Singapore at the 1977 Kuala Lumpur Southeast Asian Games (where he brought home a silver medal) when he was only 15.

Right away, he went to the 1978 Asian Games, where he was talent spotted and became the first Singaporean to be offered an athletics scholarship at the University of Houston.

Via the Singapore National Olympic Council.

Via the Singapore National Olympic Council.

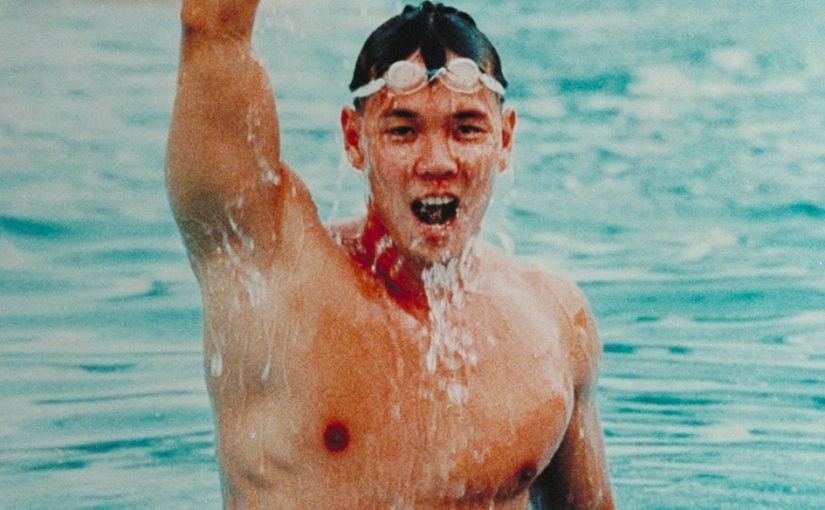

In 1980, Ang was the first non-American to qualify for the 50m freestyle sprint final at the Hawaiian International Invitational Swimming Championship.

Two years later, Ang made history for Singapore with the title of World's Fastest Swimmer, when he clinched an epic gold medal win in the 50m freestyle at the U.S. National Championship in Indiana.

By this point, aged 21, Ang set a national record of 22.69 seconds, which he held for 33 years until it was broken by Joseph Schooling at the 2015 SEA Games.

Inspired by his father

Ang got his start in competitive swimming thanks to his father, who had special access to the Farrer Park Swimming Pool.

"My dad was the pool supervisor so we had access to the pool. That's where I grew up, and spent most of my childhood."

Mr Ang Teck Bee (right) at Farrer Park Swimming Pool. Via MOH.

Mr Ang Teck Bee (right) at Farrer Park Swimming Pool. Via MOH.

Ang shares how his father used to bring him to Farrer Park Swimming Pool at 5am, switch on the lights and train him in the pool along with a handful of other students.

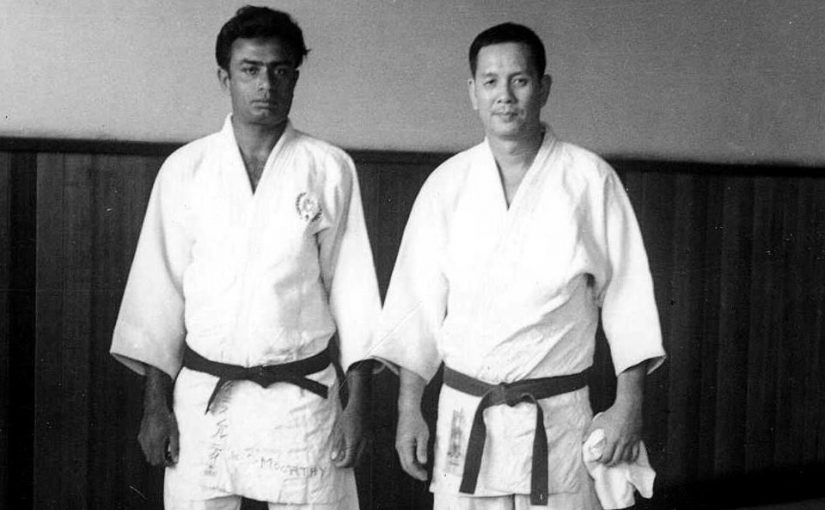

And here's another fascinating factoid: Ang's father was also a local judo champion, and the best part about this is that he learned it as a form of "up-skilling" for work.

During his time, public pools were very crowded because there were only about four to five of them in Singapore. The high demand inevitably led to rowdy behaviour among some of the people queueing up to enter the pools.

"So you have to install some 'law and order'. So my dad being a supervisor, he actually took judo up as a form of self defence and to ensure that there's some level of discipline," Ang says with a chuckle.

Ang's father was, without a doubt, a tough supervisor.

"If you ask the older generation, many of them say my dad used to ask them to cut their hair. Because that time you cannot have very long hair if you want to enter the pool or public facilities. And then you get people who are gangsters who will try to cut queue.

During the day he would work at Farrer Park, then in the evening he would head to this place called the White House. It was along the corner of Rochor Road and Bencoolen. The judo club was set up at the rooftop."

Ang Teck Bee (right). Via.

Ang Teck Bee (right). Via.

And so seriously Ang senior took his own judo training that he became a 6th dan judoka, and was even one of Singapore's representatives to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Unfortunately, though, the harsh weather conditions during his training in Japan led to rapid weight loss before the Games. He ended up being 12 pounds (about 5.5kg) short of the qualifying weight.

Despite not being able to compete, Ang's father came back to Singapore and became a judo coach.

"During his time he coached one of the most successful judo teams for Singapore. In 1973, they won seven gold medals. I think that was a feat that is yet to be repeated."

Imagine all this, while also being the sole breadwinner for his parents, wife and five kids (including Ang).

It meant that he had to give private swimming lessons in order to supplement his pool supervisor income. That was on top of the time he spent at the judo club which, according to Ang, was done out of passion.

"You can see he struggled with it," Ang says softly. "I could see it was not easy for him."

Ang's dad's situation was not unique, though. Most athletes at that time were at best amateurs who juggled training with their day jobs.

"Because that time professional sports was still not well established. So everyone would have to figure out how to juggle, find a balance. I think that is definitely one of the values that sports brings to individuals. It builds character so there is a lot more resilience."

Seeing his father pour out his time and energy in pursuit of a sport he really loved made a lasting impact on Ang himself. "Passion gave me the sustenance to pursue what I wanted to do," he says.

A sporting culture

Ang's journey to the University of Houston started at the 1978 Asian Games in Bangkok.

At that time, Ang explains that there were a couple of coaches who courted him but it was the University of Houston's coach, Phil Hansel, who came to Ang with a letter of offer immediately after seeing him perform for the first time there.

All he needed to do was sign the dotted line.

And for him, there was no hesitation at all. In fact, after his team manager went back to Singapore to discuss the scholarship with his father, Ang senior told him to go ahead with this opportunity of a lifetime.

"I think the only hesitation was finding the money to pay for the airfare," Ang quips with a laugh.

And so from 1980 to 1985, Ang swam for the University of Houston where he trained 10 times a week.

It paid off in spades. Ang clinched the World's Fastest Swimmer title in 1982 and won a gold medal in the 50-yard freestyle at the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I for University of Houston in 1983. It was also the first gold medal the University of Houston had ever won for swimming.

Reminiscing about his time at Houston, Ang shares how swimming was not as prestigious as TV sports like football and baseball.

"You realise the different level of support for sports at the university when you see that the football players and basketball players have a separate cafeteria that will serve steak practically every day. Whereas in the common dormitory cafeteria, they only serve it once a year. And you had to have a coupon!"

Despite that disparity, the university was still a place which cultivated sporting legends. Ang found himself among greats like American track and field stars Carl Lewis and Leroy Burrell, famous basketball players Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler, as well as golfing stars Fred Couples, Steve Elkington and Billy Ray Brown.

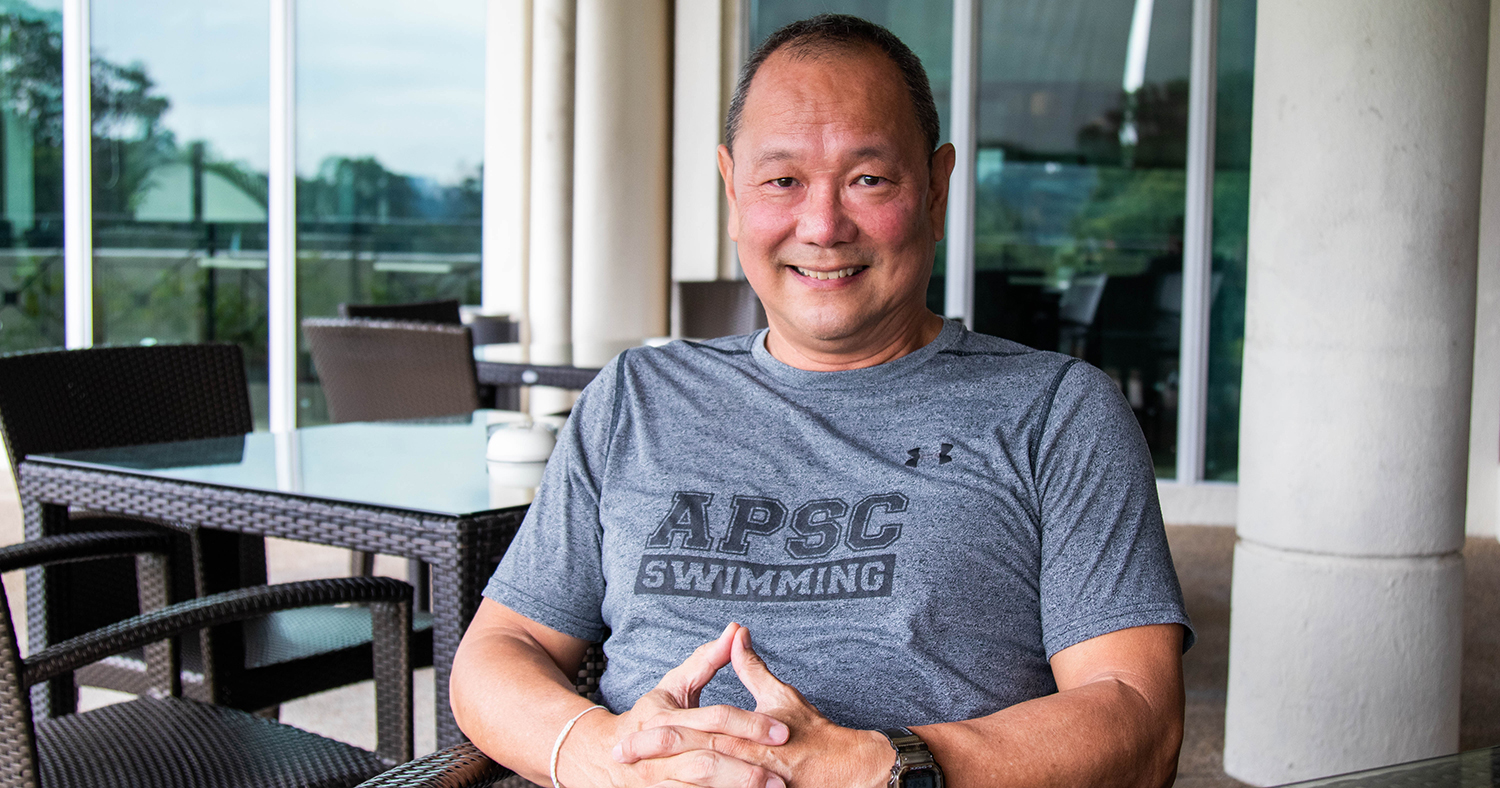

Ang thinks Singapore should cultivate a stronger sporting culture. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Ang thinks Singapore should cultivate a stronger sporting culture. Photo by Rachel Ng.

"Sports is a way of life and a culture over there. They understand the value of it. They take pride in their student athletes who are performing for the school. They really are very passionate in all the different sports."

It's a culture that Ang thinks is missing here.

While we have a sports school, Ang laments the fact that Singapore does not have institutes of higher education for sports like in the States, the U.K, Japan, and Australia, who push athletes to the next level and actively scout for sporting talents.

"If you look at the C Division (Secondary 1 and 2) athletes, they are actually faster than the A Division (Junior College) athletes. So younger kids are swimming a lot faster than the older kids. I think that is a big question mark. As they mature, they should be going a lot quicker. But they don't because the focus shifts to academics. Sports is not inculcated into the system."

"We got good universities that produce good doctors, good lawyers for the mainframe of the economy," he continues. "But if you want to grow the sports industry, you need people who are specialised in that too."

It's a culture that can be inculcated in our current universities. Ang illustrates this by pointing at the sporting rivalry between the rowing clubs of Oxford and Cambridge:

"Just rowing itself is attracting so much attention! I don't think they have scholarships. People take pride in earning their spot on the rowing team."

Racing to the Olympics

His star continued to rise during his time at Houston. Ang went on to win 20 gold medals in eight SEA Games stretching from 1977 to 1993.

His most memorable wins happened on home ground during the 1983 Singapore SEA Games where he won five gold medals for the 100m freestyle, the 100m butterfly, the 4x100 freestyle relay, the 4x200 freestyle relay, and the 4x100 medley relay.

It seemed clear that he was destined for the bigger Olympic stage.

The world's fastest swimmer in 1982 had hopes of bringing home a medal from the 1984 Olympics. Photo by Rachel Ng.

The world's fastest swimmer in 1982 had hopes of bringing home a medal from the 1984 Olympics. Photo by Rachel Ng.

In fact, right after Ang was crowned world number one in the 50m freestyle in 1982, his father told the Singapore Monitor that one of Ang's targets was to bring home a medal from the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

However, according to Ang himself, winning an Olympic medal wasn't a done deal.

"I think for me, because they didn't have the 50m freestyle until 1988. So in 1984 I had to swim the 100m. I wasn't terribly excited about it because it wasn't my pet event," he says.

"It wasn't by choice that I had to swim the 100m and the 200m. It was more a necessity," Ang laughs.

His trip to the Olympics wasn't entirely fruitless, though. Ang still managed to set a new national record time of 51.09 seconds for the 100m freestyle.

Four years later in 1988, he finally got the chance to compete in his pet event, the 50m freestyle, at the Seoul Olympics. That was the first time the 50m freestyle was introduced in the Games.

However, he missed the A finals by one place with a time of 23.39 seconds.

His missed chances to reach the pinnacle of competitive swimming for Singapore must have been quite emotional because 28 years later, Ang broke down when Joseph Schooling finally achieved what he could not.

On juggling sports and national duty

Ang's experience as an Olympian is particularly poignant considering that as a Singaporean Son, he had to walk away from competitive swimming at the peak of his prime to serve the nation after he came back from the 1986 World Championships.

For someone who was more at home in the water, Ang suffered during National Service (NS) even though he enjoyed it. He was, in his words, a "fish out of water":

"Being a swimmer, you tend to perspire and sweat a lot as compared to someone that is not exposed to the water all day. So when you go under the hot sun, basically you're drenched and you lose a lot of water. That increases your risk of heat stroke."

He collapsed from heat exhaustion during a 8km route march during his Basic Military Training (BMT) and was hospitalised due to pneumonia during his stint as a naval officer.

After two weeks into his officer training, Ang asked his Commanding Officer for a deferment to train for the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

"He wasn't too happy about it!" Ang laughs.

He was granted a 6-month deferment.

Was that enough? Ang would only offer this:

"If you look at high performance, everyone would have a good Olympic cycle to train. So if you have to get into a different routine then it'll affect your performance. My competitors had the luxury of training and preparing for the Olympics after the World Championships in Madrid."

He adds that his choice of an established swimming programme in the States was a "mistake" on his part:

"So the six months, I made a mistake by going to a distance training programme in the States. By the end of the training session I was already half-dead because being a sprinter I tend to fatigue a lot quicker. So there was an element of overtraining."

On not having enough time to train for the 1988 Seoul Olympics: "Things happen for reason," says Ang. Photo by Rachel Ng.

On not having enough time to train for the 1988 Seoul Olympics: "Things happen for reason," says Ang. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Aside from that, Ang knows for sure that he would have stood a better fighting chance if he was given ample time to train and prepare for the Seoul Olympics.

"But again, putting everything in perspective, like they say, things happen for a reason," he says.

Despite his experiences with NS deferment, Ang thinks athletes should do their NS before pursuing sports because they will then have the physical and mental maturity required to compete:

"I feel if one has to do NS, it's better to do it earlier and then move on to sports. But while going through NS, I think they need to be given the opportunity to maintain their skills because it is a specialised skill that not everyone possess.

So to a swimmer who hits 16, 17 and they have to go NS, I'd say just do it. Because the body and the mindset of the individual is still maturing and being in the army would actually help with the maturity and that will help the coaches to engage them at the highest level of training."

Retirement at 30

Ang retired from competitive swimming in 1993 not because he wanted to, but because he could not find an appropriate sponsor. According to him, sporting officials also told him that he was too old to compete.

That wasn't the end of his sporting journey, though. The then-30-year old went on to found the Aquatic Performance Swim School at Farrer Park — even buying over the pool when it closed down.

He went on to become a national coach with the Singapore Swimming Association, and trained various national swimmers for international and regional games.

And he continued competing internationally as well — in July 2000, Ang competed in the World Masters Swimming Championships where he came in first for the 50m freestyle in 35-39 age group.

In March 2002, he repeated his gold medal performance in his pet event, as well as the 50m butterfly, for the 40-44 age group.

Ang currently sits on the board of the Chiam See Tong Foundation, too, which gives out sports scholarships.

As the interview comes to an end, I am reminded that in everything he has done in and for competitive swimming in Singapore, Ang's passion lies purely in the sport — far beyond the competitive pool, the medals, and the stubborn mindset that age limits performance.

I find it remarkable that he doesn't seem the least bit bitter about his circumstances and the frustration he must have experienced as a world-champion athlete lacking adequate support from the systems he struggled so hard to succeed in, against the odds.

But, as I reflected on his four-decades-long career (and counting) in various capacities in swimming, it occurred to me how much he gave of himself to it, painful setbacks and letdowns notwithstanding.

And I wouldn't expect anything less from Singapore's very own Flying Fish.

Top photo by Rachel Ng.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.