It's safe to say that the arrival of Stamford Raffles in Singapore 200 years ago, on Jan. 28, 1819, has acquired a rather mythological status in Singapore.

On Jan. 28, at the launch of the Singapore Bicentennial this year, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said:

"Raffles made Singapore a free port. The new colony prospered, and the population grew rapidly. Immigrants came from Southeast Asia, China, India and beyond."

It was a statement that echoed the words of the late Lee Kuan Yew, on the 150th anniversary of Raffles' landing in 1969:

"When Stamford Raffles came here 150 years ago, there was no organised human society in Singapore, unless a fishing village can be called a society. There are now over two million people with the second highest standard of living in Asia."

This was despite the younger Lee prefacing his statement with a highlight of how Singapore's history stretched back centuries prior to the arrival of Raffles.

It would appear then, that despite the Bicentennial's invitation for Singaporeans to look at Singapore's longer history in the region, the dominant narrative of Raffles still holds strong — that his arrival brought strong economic benefits to our island, which made us what we are today.

Even so, criticism of Raffles has emerged in recent years, particularly over his management style and assertions that the groundwork of running a colony was effectively done by his subordinate, William Farquhar.

As part of this growing counter-narrative, I too, put forth the opinion that the dominant legacy of Raffles overlooks who he really was — a person who I found, in the course of my research, is far removed from what we learnt about him in textbooks.

And I feel it is important for every Singaporean to know the flaws of Raffles as a leader and the resulting social implications of his rule while also, perhaps, appreciating the economic benefits he brought to Singapore.

And here are my reasons why:

1) Coming to Singapore wasn't Raffles's idea

First of all, Raffles never intended to come to Singapore until the night of Jan. 27, 1819, the day before he landed on our island.

In reality, according to Kwa Chong Guan in Studying Singapore Before 1800, it had been Farquhar who had first pointed him to the general region for the suitability of setting up a trading post.

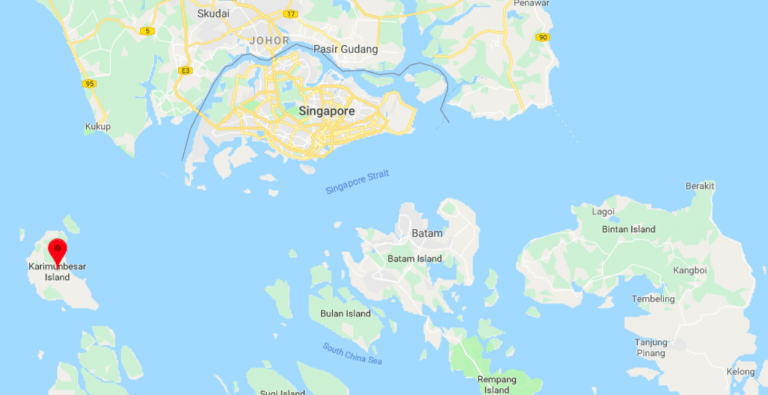

And rather than Singapore, the original destination Farquhar had suggested to Raffles was the island of Karimun, amongst the Riau Islands.

This is Karimun island. You can see Singapore, Batam and Bintan here too. (Screenshot from Google Maps)

This is Karimun island. You can see Singapore, Batam and Bintan here too. (Screenshot from Google Maps)

However, three days of sailing around the island failed to yield a suitable location to establish the trading post during the exploration in Jan. 1819.Raffles's hydrographer, Daniel Ross, suggested a particular spot on the map which "he considered more eligible than Karimun".

This spot, Kwa had written, was St John's Island, which they sailed to and anchored for the night.

On Jan. 28, the crew decided to go ashore Singapore, primarily "to make enquiries" of the Temenggong, as recorded by Crawfurd in A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries.

It was at this point, Crawfurd added, that "for the first time, the advantages and superiority of its locality presented themselves".

2) Raffles set the groundwork of a bait-and-switch that compelled Singapore's original rulers to hand over control to the British.

Raffles's motivations in coming to the region — and hence, Singapore — were also questionable, given that there exists evidence to suggest that they were purely concerned with the economic benefits the British empire could reap from doing so.

Now, to understand this fully, we need some quick context:

1) Singapore was originally under the jurisdiction of Johor — thus, it originally came under the purview of Sultan Abdu’r-Rahman, then-Sultan of Johor. His older brother, Tengku Hussein, was living in exile, and there was tension between them at the time the British arrived — something they chose to exploit.

2) So in what became called the 1819 Singapore Treaty (signed on Feb. 6 that year), the British:

a) appointed Tengku Hussein as the Sultan of Singapore, which gave him power over Singapore and its land;

b) got buy-in from the Temenggong (the governor) and the newly-appointed Sultan (who of course, would have been pleased with the British for making him Sultan) to build and operate a factory/port; and

c) agreed to pay money (in the form of half the customs duties collected from the port) to the Sultan and Temenggong, in exchange for permission to run their trading port out of Singapore.

d) agreed to pay the two rulers a monthly allowance.

Now, Kwa writes that this treaty was, according to Farquhar's successor John Crawfurd — a rather dislikable man whom I'll tell you a bit more:

"... little more than a permission for the formation of a British factory and establishment ... there was in reality no territorial cession giving a legal right of legislation. The only law which could have existed was the Malay code. The native chief was considered to be the proprietor of the land, even within the bounds of the British factory, and he was to be entitled, in perpetuity, to one-half of such duties of customs as might be hereafter levied at the port. (emphasis ours)"

What this means is the treaty essentially only gave the British permission to establish a port in Singapore.

It wasn't, at any rate, a document that gave the British any control over any land — much less control over Singapore's affairs, planning or how it should be run. In fact, Sultan Hussein was still considered to be the owner of the land under this treaty, including the land that the factory was built on.

It was a deal both the Temenggong and Sultan Hussein were very aware of, especially the money they would receive from the British.

And it was under this arrangement that Farquhar worked to operationalise trade out of Singapore.

Farquhar cooperated extensively with the local population, using knowledge of Malay culture and politics he had developed over 25 years.

Unfortunately, though, his was a considered approach that Raffles appears to have chosen not to bother with.

Tricking the Malay rulers

Kwa wrote that Raffles saw Singapore as his "child", making his subsequent dealings with Sultan Hussein and the Temenggong more imperious.

When Raffles was in Singapore for his last visit between Oct. 1822 and Jun. 1823, he negotiated a new agreement on the administration of Singapore, which increased the allowance of the Sultan but forced him to forego special privileges, such as receiving presents from the Chinese.

This new treaty made official Raffles' efforts to reduce any power and influence the Sultan and Temenggong might have thought they had under the Feb. 6, 1819 treaty.

During that period, Raffles also dismissed Farquhar and replaced him with John Crawfurd, a man disliked by both the European and Asian communities in Singapore, to implement his vision.

Under the new agreement, Crawfurd questioned the payments made to the Sultan, claiming that the agreement had not been ratified by the British Supreme Court.

Kwa wrote that Crawfurd then moved to "recover" the monies that were allegedly improperly paid by, conveniently, stopping all payments to both the Sultan and the Temenggong. This decision also very conveniently put the two rulers in debt, because all of a sudden, they owed their "illegitimately-paid" allowances that they had to pay back to the British.

Now all this, naturally, put Crawfurd in the position of advantage. He dangled a carrot in front of the Malay rulers by proposing the cancellation of their debts, a resumption of payments as agreed under the 1819 agreement and a lump sum payment of 20,000 Spanish dollars, in return for ceding control of Singapore to him.

Both resisted at first, but gave in after their allowance was withheld by the British for three months.

This resulted in the signing of "The Treaty of Friendship and Alliance" on Aug. 2, 1824, where control of Singapore was formally ceded to the British.

3) Raffles was an imperialist with a racist view of anyone who wasn't white.

But wait, wasn't Raffles able to work with the non-European races of Singapore to build it up?

Didn't he negotiate with Temenggong Abdul Rahman and sign a treaty with him on Feb. 6, 1819, along with Sultan Hussein?

Didn't he have a good working relationship with his teacher, Munshi Abdullah, as well?

At this point, it's worth revisiting what the original basis of Raffles's establishment of a trading post in Singapore was: essentially, a move of power play.

After the British gave up control of Malacca to the Dutch in 1815, under the Treaty of Vienna, they ultimately simply wanted to prevent the Dutch from gaining control of trade in the Straits of Malacca.

Raffles' intention was therefore primarily rooted in the geopolitical struggle between the European colonial empires.

And his method was to co-opt what he saw as the island's various inferior non-European inhabitants, in various ways, into helping him execute his mission.

Raffles' contemptuous views are revealed in the book Thomas Stamford Raffles, 1781-1826, Schemer or Reformer, by Malaysian sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas, who quoted extensively from Raffles' memoirs, and shared what Raffles really thought of most of the locals he worked with in Singapore.

Bootlicking Chinese

On the Chinese, Syed Hussein wrote that Raffles saw their diligence as both a useful asset and a threat, a view that he appears to have acquired during his time in Java.

More importantly, Raffles wrote that he found the Chinese to be shrewd bootlickers who were highly effective at enriching themselves.

"...the monopolising spirit of the Chinese frequently exercises a very pernicious control over the necessaries of life, and the produce of the soil, even in the vicinity of Batavia (present-day Jakarta). If we consider the suppleness and insinuating address of the Chinese, how apt they are on all occasions to curry favour, how ready they are to proffer assistance when there is no danger, and when perceive that it falls upon their own interest, we may depend upon their utmost efforts being used to ingratiate themselves with the English."

Raffles also saw the seeming incapability of the Chinese in integrating into colonial societies as another reason for their economic prowess:

"...the Chinese, from their peculiar language and manners, form a kind of separate society in every place where they settle, which gives them great advantage over every competitor in arranging monopolies of trade."

Raffles cautioned his compatriots that it was therefore important for the British to keep the Chinese at arm's length lest they gain political power at their (the British) expense.

Pioneering the "Lazy Malay" myth

However, it is in Raffles' view of the Malays that one finds the best expression of the links between Raffles' racism and his plans in developing Singapore.

Syed Hussein wrote that Raffles primarily saw the Malays as lazy "savages", resistant to civilisation and easy to please, as a result of the tropical climate that they lived in that yielded food in abundance.

Recently, former Minister Yaacob Ibrahim also highlighted this "most toxic myth of the lazy native", adding that the myth has been studied and debunked extensively by Syed Hussein in his famous book entitled "The Myth of the Lazy Native".

About the only redeeming feature of the Malays, Raffles said, was that their self-reliance in the area of defence gave them control over their emotions, thereby making them "the most correctly polite of all savages".

In Raffles' own words, as cited by Syed Hussein:

"The Malay, living in a country where nature grants (almost without labour) all his wants, is so indolent, that when he has rice, nothing will induce him to work. Accustomed to wear arms from his infancy, to rely on his own prowess for safety, and to dread that of his associates, he is the most correctly polite of all savages, and not subject to those starts of passion so common to more civilised nations."

Syed Hussein added that Raffles also blamed the "degraded" conditions of the Malays on exploitation by the Dutch, Chinese, Arabs, and the Malays' own rulers, which solidified Raffles' belief that it was up to the British in uplifting the Malays' lot and bestowing upon them justice and prosperity.

So how did we end up glorifying Raffles?

With all that's been said about Raffles' racism and manipulation in gaining control of Singapore, how did Singapore end up glorifying him and crediting him for all the things he did to and for us?

As Kwa suggested in the introduction of the book Studying Singapore Before 1800, the glorification of Raffles's contributions was instrumental in constructing Singapore's national history.

Much like how Raffles supposedly transformed Singapore into a thriving trade hub, this "surviving against all odds as a vulnerable city-state" narrative served Singapore well in its immediate post-independence years.

This narrative allowed Singapore to identify itself as a global city-state, elevating ourselves to the global stage.

But of course, it's 2019, two hundred years on, and it's high time we moved on from this.

Others have done far more for the development of Singapore with far more benign motives.

I present exhibit A (click the picture to go to the PowerPoint presentation we did on Facebook):

And of course, this guy:The end.

Top image from Singapore Bicentennial Facebook page

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.