DISCLAIMER: All op-eds published on Mothership, including this one, represent solely the opinion of their authors, and not the stance of the website or company or group of people it represents.

Here's something I'm not sure anyone in Singapore has said before: even though I wouldn't think of myself as wealthy, I'm actually willing to pay more than I currently do in taxes.

Of course, the wealthy should pay more

There is certainly much to be said in favour of making the wealthiest of Singapore's society give back the most, and I fully agree with and support the case that has been made by individuals far more qualified to do so than I.

Ideally, more should be done to tax the rich, such as implementing wealth taxes, which the government hasn't really looked into and I really wonder why — as pointed out by Calvin Cheng last year:

And also economist Donald Low, in more fully-fleshed out arguments this year:

Other than wealth taxes, there are also options like capital gains and inheritance taxes, but in the event that implementing these still prove insufficient, I would argue that there is room for some of us, in certain income tax brackets, to pay more.

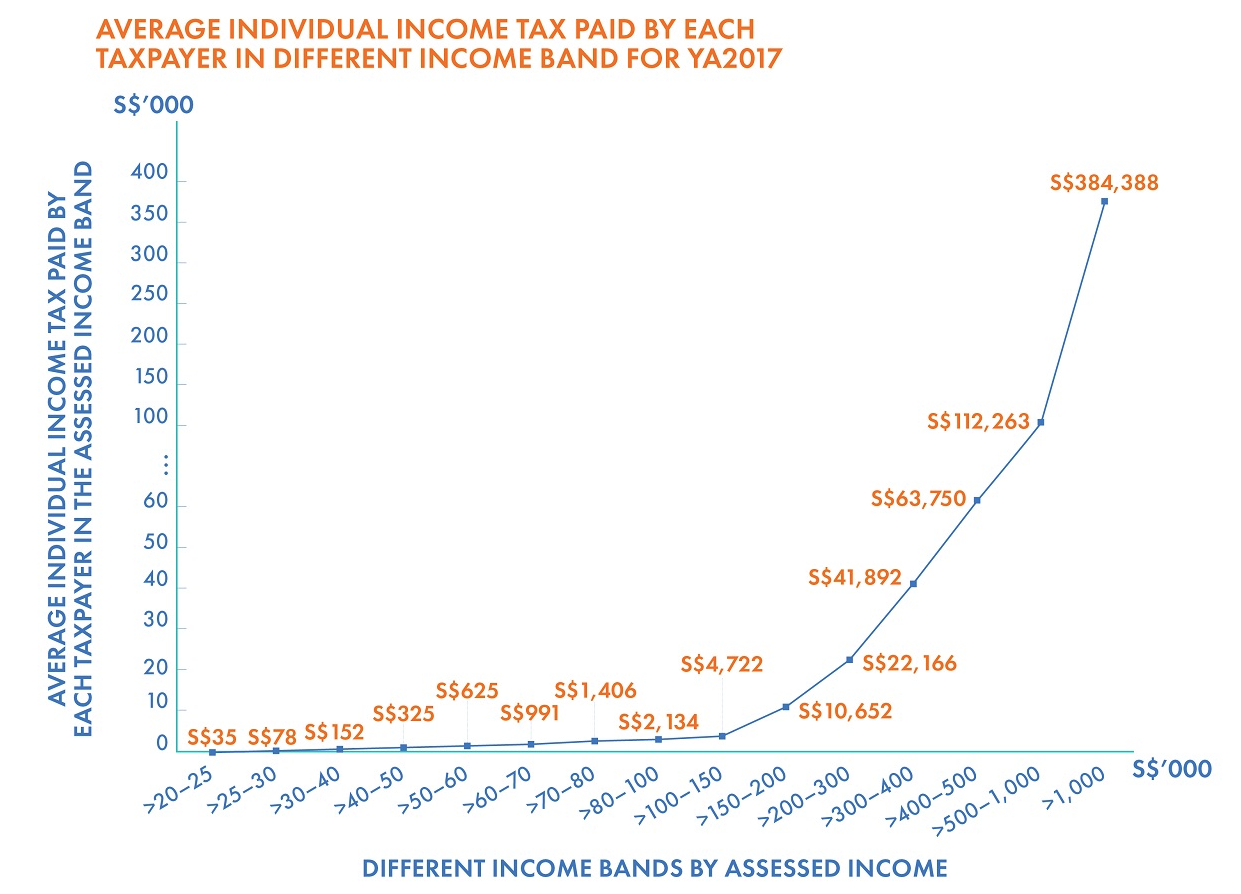

Just for our understanding, here's how much taxes have been paid by people from various income brackets two years ago:

This graphic's from IRAS's website.

This graphic's from IRAS's website.

Meet me, a higher-than-median income earner

Now, according to the Ministry of Manpower, the median monthly income for a full-time employee in Singapore is S$4,437.

There doesn't appear to be any clear or official definition of "middle income" here, even though this term is frequently used to refer to what is a presumably large group of us gainfully employed people in Singapore, on occasion paired with the term "sandwiched" between the super rich and people who are really in need.

So for the purposes of making my case, I take reference chiefly from my personal circumstances, which I should set out as:

- belonging to the higher-than-median income earning group,

- being in a position to incur healthy debt (e.g. the three-room flat I own and pay for),

- not having children or elderly dependents or helpers or caregivers I need to provide for,

- being able to pay my credit card bills every month, and perhaps even

- being able to take the occasional (at least once per year) holiday.

As a slightly-higher-than-median-income earner, I paid (significantly) less than S$1,000 in tax last year — which I honestly would say is, for me at least, extremely reasonable.

And even though both my husband and I work full-time, I have no children or elderly parents or grandparents living with me, I get reliefs that offset the amount of my income that is assessed —

- just for being part of the workforce (earned income relief)

- for donating to charity (2.5 times of the total amount I declare that I have donated), and

- for putting part of my salary into CPF (because I don't contribute more than S$6,000 per month to my ordinary account).

So why am I thinking about whether I'd be willing to pay more in income taxes?

Because the government says we need more money.

We always do, right? Costs are always on the rise (inflation, yo), Singaporeans are growing older (and we're not giving birth to enough babies to adequately balance these people who are growing older and who need more care), and we're building more train lines.

The issue of where the government gets its money for all the things it needs to spend on, build and pay for is a perennial one.

And there's a long list of places where they can find it, and mine it, including but not limited to this list:

So why take it from income tax if the gahmen makes money from other kinds of taxation?

Well for one thing, they've decided to raise the GST.

You'd likely remember that at last year's budget, Minister Heng announced that the government will be raising the Goods and Services Tax to 9 per cent (it's currently 7 per cent) "between 2021 and 2025".

I personally am not in favour of raising the GST, vouchers and other government fiscal transfers notwithstanding, because it hurts everyone who buys things in Singapore — i.e. the poor, too.

Certainly, the government may have worked it out to ensure that, according to Minister Heng, lower-income Singaporeans will receive S$4 for every S$1 they pay in tax. And even the middle-income will get S$2 for every S$1 we pay.

It's undeniable, though, that its effect on the prices of essential goods and services in particular will be keenly felt.

Taxing online services like Netflix and Spotify Premium is par for the course — after all, most folks who can pay for these are likely able to afford a higher GST too.

But raising a universal tax like the GST isn't just unpopular — without going into the math (because I can't), I venture that there are other ways to raise more money than by adding burden on the poor that can offset the GST hike.

Low, again, said this too:

Conversations have also been had about corporate taxes — a big source of tax revenue — but raising these would definitely more directly impact our competitiveness and business-friendliness than any decision to adjust personal income taxes, so that to me is even further from the question.

But raising personal income taxes affects Singapore's competitiveness too, right?

That's what's often said indeed. Almost every time it's brought up, too.

Like last year, when my MP, Intan Azura Mokhtar, suggested that income taxes should go up, Minister Heng cited this as his reason for not doing so:

"Any review of personal income taxes must ensure that Singapore remains attractive. Just yesterday, Hong Kong has announced a reduction in personal income taxes in their Budget.

We will be moving in the opposite direction if we are to raise personal income taxes when all jurisdictions are competing for talent, including our Singaporean talent.

We will continue to monitor and review our rates, but for now, our view is that existing PIT rates are reasonable for us to remain attractive given the intense global competition for talent."

But maybe it's not as bad as we think.

Let's look at the highest bracket tax rates across a sampling of some other places right now:

- Hong Kong: 17 per cent (assessable income of S$55,000 and up)

- Taiwan: 40 per cent (assessable income of S$200,000 and up)

- China: 45 per cent (assessable income of S$200,000 and up)

- Indonesia: 30 per cent (assessable income above S$50,000)

- Malaysia: 28 per cent (assessable income above S$330,000)

Singapore's the second-lowest of all these, at 22 per cent for assessable income of above S$320,000.

And even if you were to say that Hong Kong's tax rates are more competitive than ours, bear in mind that their maximum threshold kicks in at the S$55,000 assessable income mark — for a Singapore tax resident with that assessable income level, the rate is just 7 per cent in comparison.

So in Hong Kong, a lot of the middle income (those with assessable incomes of between S$55,000 and S$320,000) are caught in the 17 per cent band. In Singapore, however, a 15 per cent rate applies for incomes upwards of S$120,000, and it goes up to 18 per cent at the S$160,000 mark.

What I'm saying, if these numbers washed over your head in a blur, is a lot of tax comparisons by country can't be done universally because countries tier their taxation systems in different ways.

Besides, even if you want to say that our highest tax rate is higher than Hong Kong's (in the case of the super-rich), we can then take the discussion up on other factors, such as the robustness and efficiency of the business environment and the quality of life between the two places.

So in Singapore, my case is that maybe some of us can afford to shell out perhaps an additional few hundred bucks apiece, just once per year?

Now I have (or at least I think I have) covered broadly the arguments against raising taxes, I'll move on to why I, at least, am convinced that if the need should arise, I'm willing to pay a bit more in taxes.

1) For a truly more inclusive society.

The term "inclusivity" has been bandied about by our political leaders to the point where I personally am quite sick of hearing it.

But I fully back the concern and the idea.

We should — in fact, I feel it's our responsibility to — do whatever we can to uplift our fellow citizens who happen to be having a slightly tougher time getting by, and who may have started out slightly behind in whichever way in life — financially, a tricky family situation, mental or physical or psychological disability, you name it.

Sociologist Teo You Yenn writes in This Is What Inequality Looks Like that the problem of poverty is "ghettoised" — putting the idea of helping people in need in the context of "charity" and "help" gives one the idea that helping the poor lies "beyond public responsibility":

"This way of framing the problem of poverty isolates it — detaches the issues and challenges faced by a small minority of the population from those faced by everyone else. It dislodges the issue of poverty from the broader political economy in which it is produced. Importantly, it frames public interventions as 'charity', as 'help' — in other words, beyond public responsibility — and recipients as recipients rather than as members of society with rights to certain basic levels of well-being and security."

No one can deny that resources would, and do help a person in a tough spot. I, for one, can absolutely appreciate the importance of having state resources to uplift those in need, having personally also been a beneficiary of these — bursaries, small scholarships here or there, transport vouchers, MOE financial aid and more that slips my limited long-term memory space, just to name a few.

And I didn't just benefit from these. One type of aid that truly made a difference to me was what my older friends bestowed on me in my youth — the S$2,000, for instance, that a kind friend gave me without question for my university laptop (I made sure I paid it back while still in school or almost as soon as I graduated), and all the tuition gigs my friends' parents gave me for their children or nieces or nephews.

The personal examples I shared above make the point that interpersonal help is wonderful and meaningful, but whether it's sustainable is a whole other issue, for this very reason. I was privileged to know and be friends with people who were in a position to help me, and not many people would necessarily have these.

Say what you want about our government and its flaws, but it has the information. It knows our people. It knows best (perhaps not perfectly but arguably decently) who needs help and where and how best to help them through the resources they have deployed to study the ground.

So why not lend them a hand, help them to help the needy better, right? Taxation is, if you think about it, trusting the government with our money to make the best use of it to benefit the citizens of the country it runs.

2) And if you don't trust the government to make our society more inclusive, do it yourself (and claim tax rebates from donations).

The government, I believe, would love for its citizenry to play an active role in making our society a better place.

Civil society and stepping up to help groups of fellow human beings in need is a great thing, and volunteerism is highly encouraged — the best way the government knows how to do this is by offering tax deductions whenever a Singapore tax resident donates to a registered charity.

Right now, they're giving a 2.5x deduction off your donations made in the financial year 2018 for this year's tax assessment. So if you are against paying money to the state to do the necessary work (i.e. in providing things the public needs but which nobody finds it worth paying for at a cost they deem reasonable), and prefer to know where exactly your money is going, donate generously to your preferred charity.

And declare it in your tax return.

3) It's really not that painful if you think about it.

For young working adults like me who don't run companies and such, the main taxes we pay for (apart from GST) would be income tax and property tax (unless you also own a car, which would then require you to pay road tax).

Both of these are one-off annual payments. As a homeowner too, I pay property tax on my three-room HDB flat. And from the past few years of my experience owning a house, it's either been zero or negligible.

After I throw in my income tax, I still am not entirely feeling the pinch as much as I would, say, paying for a holiday.

Certainly, there are many folks who may earn what looks like a sizeable income but may have to support ailing parents, bedridden siblings who need round-the-clock specialised help, multiple kids and a stay-at-home spouse, and may not also feel that the existing range of reliefs are of sufficient amounts to defray the amount they ultimately still have to fork out.

That's how I think of this, I suppose — the amount I pay to the government in taxes is in most circumstances less than or equal to what I would pay for a holiday, or a few big meals at my favourite restaurant.

Sure, you can say you can choose to save the money or forgo that holiday and fancy meal if you didn't want to do either, but you can't choose whether or not to pay your taxes. True, I agree.

But I suppose I think of it as my duty to the nation, and to society — a once-a-year, really not that painful payment that I will forget about as quickly as my monthly contributions to charity, insurance, savings and parents.

Anyway, my point is, in my current circumstances, I do feel that I can afford to pay a little more in taxes, and I, for one, am prepared to show this willingness to contribute so that the government doesn't have to turn to regressive measures that hurt the poor.

Minister Heng's decision regarding this has already been made, but this is perhaps just another point of view to consider this year, as we enjoy our S$200 off our tax payments in this year's Bicentennial Bonus.

Top photo by Jeanette Tan so no, she isn't in the photo. Don't try to spot her in it.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.