There was really no good reason for 37-year-old Kay Kyeongsik Woo to invest in Singapore.

For starters, he's South Korean — as you might guess from his name.

The father of one has a Master's in Statistics from Columbia University and a good business going with a chauffeured vehicle service platform back home and across Asia called easi6.

All this makes us even more perplexed that Woo would devote time and energy into developing TADA, a small non-profit ride-hailing app that was launched here in July 2018.

Yep, non-profit indeed — Woo's company does not take any commission from drivers' ride fares, a drastically different operating model from Grab and Go-Jek, which take 20 per cent in commission from their drivers.

Starting an app here was never part of the original plan

And sure enough, TADA wasn't actually part of his plan. Woo had originally ventured out of South Korea in search of expansion opportunities for easi6 in Southeast Asia in 2016.

However, during his time here, Woo saw that the ride-hailing market, which was dominated (at the time) by Grab and Uber, actually still had space for smaller players.

At the same time, it was an opportunity to test a business model using blockchain — which is what TADA's parent company Mass Vehicle Ledger (MVL; pronounced "Em-Buhl") does.

But the larger reason to compel Woo to even consider doing this was a series of conversations he had with drivers with various taxi and ride-hailing transport companies during his "research" visits here.

It was these, he explains to us in a recent interview, that gave him clear indication there were what he describes as "gaps" left by the larger companies — which, when he found them, he simply couldn't ignore.

The trouble with using cash incentives

After the acquisition of Uber's Southeast Asian presence by Grab, Woo said he observed that on the whole, it seemed to him that drivers (and riders too, actually) were getting increasingly concerned about what they perceived to be the negative impact of a lack of market competition.

Common complaints Woo says he heard from drivers included fewer incentives for both drivers and riders, more expensive fares, and feedback that they said fell on deaf ears.

"Interestingly after consolidation, the quality went down. The customer satisfaction level went down, drivers' income level also went down."

Drivers also complained about not feeling valued, and that they were unable to earn as much as before, he said. They had to work more hours in order to reach past income levels.

After thinking about all this, Woo told us he has a good idea why all this was happening: using cash incentives as a form of reward (what he calls "cash burning") creates a "fake volume" on top of original ride-hailing demand.

Hence, when the incentives dry up, the level of demand falls back to the number of people willing to pay for the actual cost of ride-hailing.

"Drivers are being treated in a very bad manner and their income went down. How can they provide a good service?"

"I'll just say 'yes sir, sorry sir, no sir'."

But the most heartbreaking story for him, and perhaps the one that stirred him into action, was the case of a 60-year-old driver who was previously suspended on another app, possibly due to a user review. However, the actual reasons for that were not communicated to him.

"He mentioned to me that there's a quote that he would tell himself. It's very bad, but he would start his driving by saying to himself, 'I'm a dog, I'll just say yes sir, sorry sir, no sir.' I was like, why do you do that? You don't need to do that. I couldn't understand what was going on."

This, regrettably, doesn't appear to be an uncommon scenario. Trawl any number of local driver groups on Facebook and you'll come across stories of drivers who opine that big ride-hailing players are find it easier to pin the blame on drivers when conflicts arise.

And because of stories like this, Woo said he was convinced of the importance of trying out the model he had in mind for TADA — even though serving the ride-hailing community was not in MVL's original roadmap.

And why Singapore? Here's what Woo had to say:

"Among all the Southeast Asia countries, Singapore is the most developed country and the customers and drivers are all educated. We don't even need to spend money on educating drivers and customers (to use apps to book rides). They're ready to accept a new service that doesn't hurt their user experience."

Just over half a year on from when he first started things, the company has grown to more than 30 employees.

MVL's office. Image by Rachel Ng.

MVL's office. Image by Rachel Ng.

The TADA model? Trading data for full fare earnings

From the outset, Woo said the method of using cash incentives is unsustainable for a small company like MVL.

"It's really hard to manage the quality of the driver without giving them an incentive. But there is no such way that we can give them (cash) incentives. For a start up like us, even if we get an investment of a couple of million dollars, you can burn that cash a couple of months later if you (use it to) give out incentives."

Woo shares that using blockchain — in the form of data and tokens — helps to circumvent this dilemma by giving out an incentive without hurting the business.

Simply put, each driver, through the rides he takes up, accumulates data such as driver location, driving distance, and driving behaviour. In the era of Big Data, this is all valuable information that third parties are very ready to pay for.

Woo shared that his company has collected about four months worth of data, and will have to accumulate at least a year to two years' worth for it to be of substantial value.

He is quick to clarify, though, that the data ultimately belongs to TADA's drivers — MVL only functions as a facilitator:

"We define the ownership of the data first and then we facilitate [the sale]. Bigger players will claim that the driver data belongs to them, so that they can do whatever they want with it.

We don't do that. The data belongs to each individual who contributed it. Your data is your labour, so you should get rewarded for it."

With the consent of their drivers, MVL sells it to third-parties who use it for research or insurance purposes, for example. In exchange for giving up their driving data, drivers get tokens (a form of cryptocurrency) which can be used to pay for services.

Right now, these tokens can't buy anything just yet, but Woo said he's trying out the MVL cryptocurrency in Cambodia now and if the results of those trials are good, he may roll it out in Singapore too.

In the meantime, drivers on TADA take back all their trip earnings while accumulating MVL tokens which (hopefully) can be exchanged for services soon. Users who leave detailed feedback for drivers can also earn tokens.

And so where do their current earnings to pay their staff and keep their lights on come from? Woo tells us MVL earns an "agent fee" each time they sell a driver an insurance package from one of their partners. It also earns a little when drivers rent cars from the five affiliate rental companies it works with.

Putting more faith in drivers

One can hardly call today's ride-hailing industry a "virtuous" one. In fact, we are bombarded almost daily with stories of riders from hell:

... and, from time to time, drivers who make life stressful for their riders:

Woo posits that this sorry state of affairs stems from bigger players trying to compel drivers into fulfilling certain objectives, which in the process creates unnecessary conflict.

Take for example the oft-complained-about cancellation rate. Drivers cannot exceed a certain rate target or else they will forfeit an incentive. This can lead to a lot of unhappiness between drivers and riders.

Woo related an experience he personally had of a "big fight" that he had with a driver in Vietnam.

"I was calling for a car with two big luggages. This driver arrived and he said, 'You have too many luggages. I'm not going to take you.' He told me to cancel my order."

"I was like, no, you go ahead and cancel," he said. "If you don't want to take me, you can cancel my booking."

According to Woo, the Vietnamese driver kept shouting at him, insisting that he cancel the booking instead. "I was very surprised that the driver would do that to me," he says.

In the end the driver cancelled the booking, but that incident left an impression on Woo.

"The community (of drivers and riders) can manage themselves. They have their own free will to use this tool (a ride hailing app) to maximise their own income. They don't need the special rule of cancellation or acceptance rates. But if you try to control them, that's the beginning of the problems."

In line with this philosophy, Woo decided TADA would not impose a cancellation rate or acceptance rate on drivers. Instead, drivers are incentivised for providing their driving data while riders get tokens for leaving honest reviews.

It is a system that puts a lot of faith in drivers, and we'll be honest here: we're not sure if it's the way to go.

However, TADA has its fans. To date, it has 23,000 registered and active drivers and 150,000 riders, and both figures are growing.

Listening to riders and drivers

Woo's philosophy extends into its customer service too, which is part of what MVL brands as a "trust-driven ecosystem".

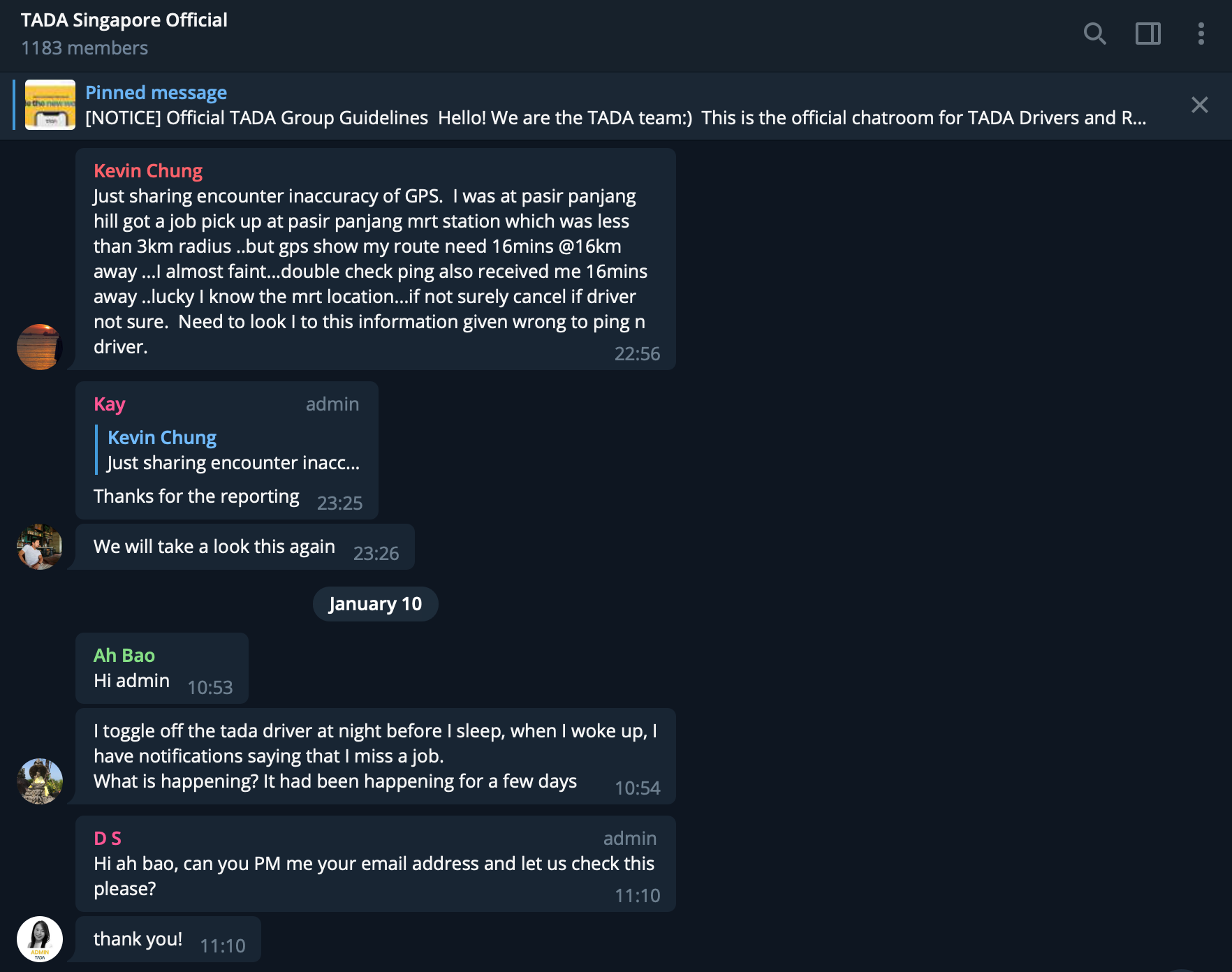

On TADA's public Telegram group, TADA Official, more than a thousand members, made up of drivers and riders, post questions, feedback and suggestions, and get pretty prompt responses from the MVL team — including Woo himself:

The TADA Telegram group chat.

The TADA Telegram group chat.

The Telegram group also serves as a channel for TADA users to flag bugs in the app which the MVL team can troubleshoot. Woo said the TADA app has been updated more than 50 times since it launched thanks to feedback like these.

And apart from putting faith in its drivers, Woo said it's of paramount importance for TADA to earn the trust of its drivers. Looking at the way they deal with user feedback, it seems to us this is consistent with what he's told us.

"We are a small potato"

In what must have been a coincidental twist, we happened to have met Woo on the same day Go-Jek launched its beta app in Singapore.

Woo using the Tada app. Image by Rachel Ng.

Woo using the Tada app. Image by Rachel Ng.

But Woo was quick to state up front that he does not see TADA as a rival or competitor to the green giants.

"We are a small potato, we are very small," he said, instead choosing to see TADA as complementary to them.

"I hope to build a strong community between riders and drivers. Even with Go-Jek's entry into the market, I think that is good for the driver and rider. Drivers can enjoy better opportunities with more competition and customers can enjoy more choices. We want to grow bigger, but not the traditional way."

This sounds like a long shot to us from where we're standing right now, but Woo believes that growing to Grab or Go-Jek's size via his cryptocurrency model is not a pipe dream.

"We want to take our time, we want to build the trust. We believe sooner or later, the momentum will come, for us to grow faster."

All images by Rachel Ng. Woo's quotes were edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.