You might recall the term "PISA" for that test our 15-year-olds take in math and science.

It had questions like these:

And of course, us being who we are, came up tops in the 2015 PISA rankings:

But anyway, the PISA is conducted by the international Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which analysed the 2015 PISA results and generated a report that examined education equity across these 72 countries and economies.

This report, which highlights education systems with a lack of equity, was released on Tuesday, Oct. 23, and is certainly timely considering the recent national conversation on class divide in schools.

It also refers to "disadvantaged students", which it defines as "those whose values on the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status are among the bottom 25 per cent within their country or economy".

Stay with us, this may get a bit heavy —

Here are the key findings you need to know about disadvantaged students in Singapore:

- Effect of socio-economic status: 16.8 per cent of the variation in science performance among Singapore students can be explained in terms of students' socio-economic status. This is higher than the OECD average of 12.9 per cent. The higher the percentage, the more weight socio-economic status has on academic performance (i.e. this isn't so good).

- Low national resilience: Only 9.5 per cent of disadvantaged students are found in the top 25 per cent of science performers in Singapore. This is lower than the OECD average of 11.3 per cent (i.e. this isn't so good either).

- High international resilience: Almost 50 per cent of Singapore's disadvantaged students attained the top quarter of science scores internationally, performing better than what their circumstances would otherwise predict. This is higher than the OECD average of 30 per cent (i.e. this is a good thing).

- High core-skills resilience: 43.2 per cent of disadvantaged students attain proficiency level 3 in science, reading, and mathematics (the highest level is 6). This is higher than the OECD average of 25.2 per cent (i.e. this is also a good thing).

[related_story]

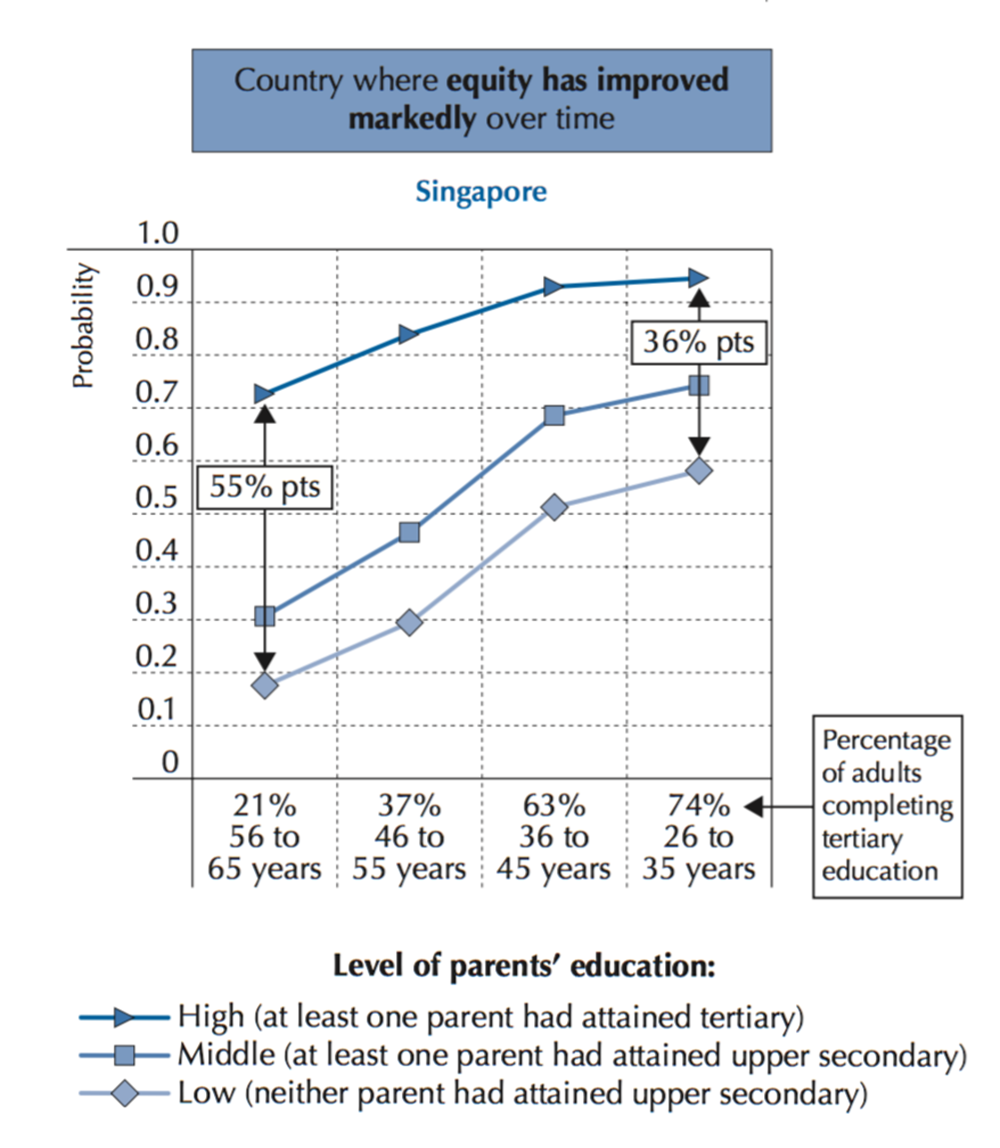

Aside from data on disadvantaged students, the PISA report specifically highlighted Singapore as the only country (among those who submit data) where attainment of tertiary education (degree or diploma) "improved markedly over time", improving by 19 percentage points (And yep, this is a pretty great thing too):

Here's what the report says:

"In Singapore, the difference in the likelihood of completing tertiary education related to parents’ education narrowed by 19 percentage points between the oldest and youngest cohorts. What is unique about Singapore are the enormous strides made by adults with low-educated parents.

In Singapore, even disadvantaged adults in the two youngest cohorts were more likely than not to complete tertiary education (i.e. among those with low-educated parents, the probability of completing tertiary education was 51% for adults aged 36-45 and 58% for adults aged 26-35).

Arguably, this was possible because the stratum of socio-economically advantaged adults had already reached a “saturation” point in their access to tertiary education by the 1980s, when 86% of adults with tertiary-educated parents also completed tertiary education."

MOE's take: lift the bottom, instead of capping the top

One of the "not so good" findings from the report is that disadvantaged students in Singapore have low national resilience.

In other words, there's a very big gap in terms of performance between high- and low-SES students.

But again, disadvantaged students in Singapore have a higher probability of outperforming their international counterparts (high core-skills resilience and high international resilience).

In a July parliamentary speech, Education Minister Ong Ye Kung said some suggestions to close this gap included banning tuition centres or limiting the resources given to popular schools.

He said, however, that his ministry’s approach is to lift the bottom by allocating them more resources instead of capping the top.

"Bottom" here refers to three groups of students: Disadvantaged students, high-needs learners, and students with special education needs.

Some examples of lifting the bottom include:

- Allocating more financial resources to specialised schools and Normal Streams

- Regular rotation of teachers among all government schools

- Smaller class sizes for weaker students

The effect of lifting these groups gives them access to more opportunities that were once open to those who could afford them. It also gives them the opportunity to interact with students of diverse backgrounds.

The report concluded that "no country in the world...can yet claim to have entirely eliminated socio-economic inequalities in education".

More background on the PISA test scores and how we did:

Top image via Raffles Institution Facebook page.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.