Kenneth Paul Tan is an Associate Professor at the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

In 2018, he published a book titled Singapore: Identity, Brand, Power, identifying the contradictions that arise from Singapore being a multicultural nation-state and a cosmopolitan global city. Tan also explores the strategies and processes involved in managing such contradictions.

"A Global City: Inequality and the degeneration of meritocracy", a section within his book, is published here.

***

By Kenneth Paul Tan

Since the mid-2000s, the government has further liberalised Singapore’s already open economy, accelerating the inflow of foreigners who now make up a third of the population.

Singaporeans, not generally known to be xenophobic, have started to complain about overcrowding in their city and breakdowns in their transport infrastructure, often suggesting that the immigration policy is to be blamed for this.

Ironically, though, the economy has become so dependent on low-wage and low-skilled foreign workers that subsequent efforts to raise productivity and invest in technology have met with opposition from small and medium-sized local companies that argue they will be forced to go out of business or have to raise their prices, which will then raise the cost of living.

For the government, restricting the inflow of foreign workers and investing in productivity-raising technology can also be politically costly.

Singapore attractive to the super-rich

Photo via Singapore Summit Facebook page

Photo via Singapore Summit Facebook page

A significant number of the super-rich, such as Eduardo Severin, Nathan Tinkler, and Jim Rogers, have invested and relocated in the now-hip city.

Photo from Jim Rogers' Facebook page

Photo from Jim Rogers' Facebook page

A report by property consultancy Knight Frank predicted that Singapore would see "the world’s largest influx of super-rich individuals over the next 10 years".

The attraction for them lies in Singapore’s regional financial and transport hub status, its stable and pro-business government, and the large concentration of MNCs.

However, the consumption patterns of the super-rich have helped to push up the cost of living, making Singapore an expensive city to live in.

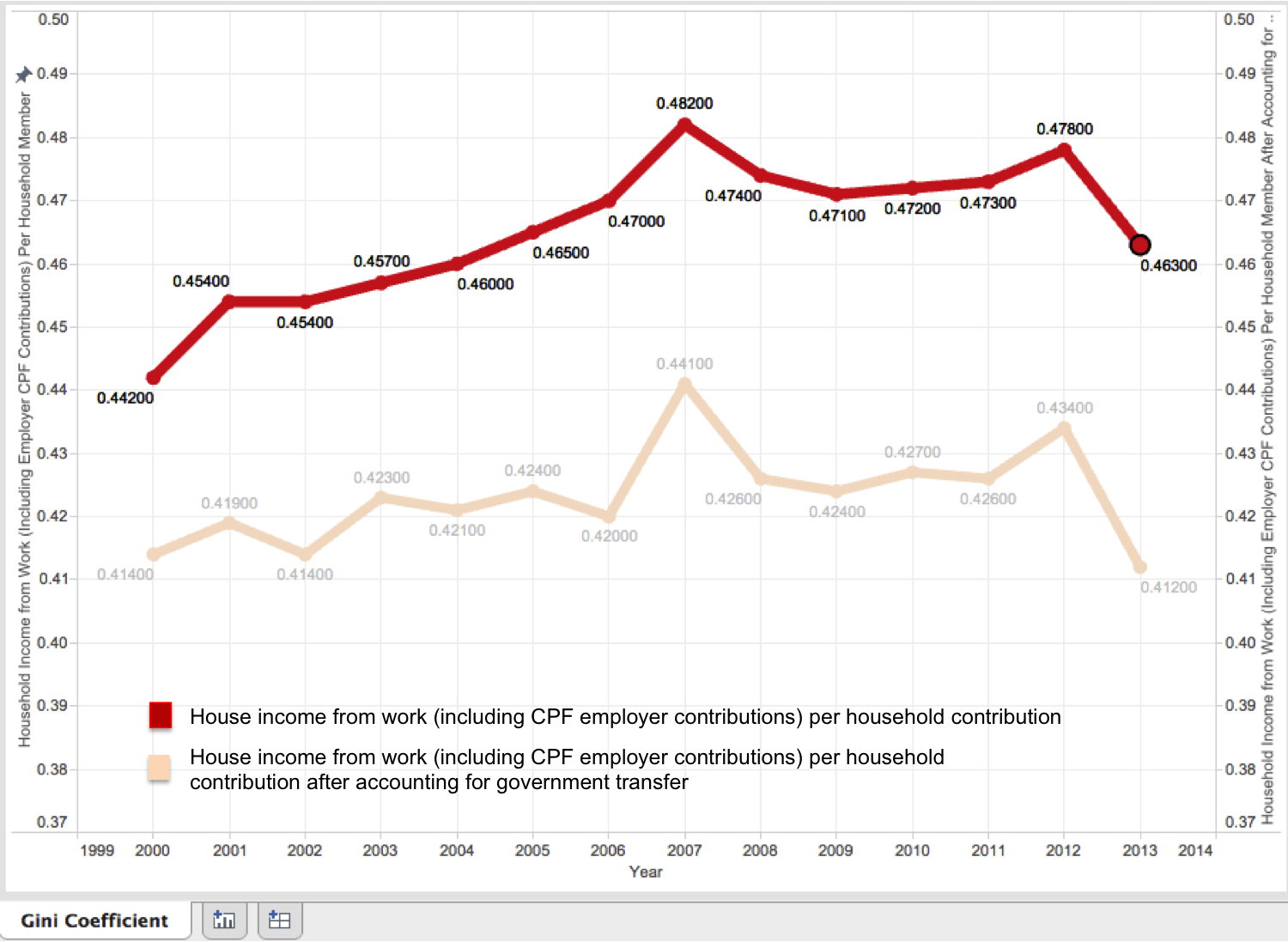

Income inequality as measured by Gini coefficient

As noted earlier, top earners in Singapore compete for internationally benchmarked salaries.

Middle-class incomes have been stagnant even as the country rises up the ranks of the wealthiest nations. And the lowest earners experience downward pressure on their wages as they compete with nearly a million low-waged migrant workers from the region.

Graph via SMU wiki

Graph via SMU wiki

Singapore’s income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has reached highs of 0.482 in 2007 and 0.478 in 2012. UNHabitat describes inequality within the 0.45 to 0.49 range as:

approaching dangerously high levels. If no remedial actions are taken, could discourage investment and lead to sporadic protests and riots. Often denotes weak functioning of labour markets or inadequate investment in public services and lack of pro-poor social programmes.

After accounting for government transfers and taxes, however, the Gini figures are 0.439 in 2007 and 0.432 in 2012, and they do look to be declining with the cautious introduction of more progressive policies.

In 2007, among OECD countries, the average post-transfers figure was 0.317, the highest was 0.480 (Chile), and the lowest was 0.240 (Slovenia). In 2012, the average was 0.316, the highest was 0.471 (Chile), and the lowest was 0.249 (Denmark).

While the Gini coefficient might seem like just an abstract notion of income inequality subject to various statistical peculiarities, in a densely populated city like Singapore inequality is palpably experienced at the day-to-day level of the person-in-the-street.

Singapore: a highly unequal city

Juxtaposed uncomfortably, for instance, are images of ostentatious lifestyles of the wealthy and images of elderly Singaporeans who collect and sell discarded waste in order to make ends meet; images of luxury cars on the ever-expanding road network and images of crowded trains and irate passengers stressed out by regular breakdowns.

Photo via Tan Chuan-Jin's Facebook.

Photo via Tan Chuan-Jin's Facebook.

Sociologist Teo You Yenn addressed the tensions and contradictions of highly wealthy and highly unequal Singapore through a very illuminating ethnographic presentation of the experience of low-income Singaporeans and a critical analysis of the structural and cultural conditions that reproduce inequality and poverty.

Global flows affect inequality

Inequality in Singapore is exacerbated periodically by globally induced economic and other forms of crises, which continue to hit globally dependent Singapore in more unpredictable and protracted ways, affecting poorer and richer Singaporeans in very different ways.

Expectations of continued economic success have been moderated.

With anticipated disruptions to the economy and the future of work, characterised in terms of automation and artificial intelligence, there is every likelihood that the pool of absolutely poor Singaporeans – the working poor, unemployed poor, and poor retirees who belong to an estimated 110,000 to 140,000 households – will expand.

Inequality reinforces societal cleavages

For the absolutely and relatively poor households, it will be significantly harder to make ends meet, while the government maintains its restrained approach to redistributive practices, arguing that wealth generated from economic growth by the economically successful will eventually trickle down to the bottom.

With Malays over-represented among poorer Singaporeans, starker inequality may reinforce the traditional social cleavages of race, religion, and language and give birth to newer ones between older and younger generations, locals and foreigners, and so on.

The accelerated presence of foreigners, most of whom are in Singapore on temporary terms, has the effect of hollowing out the Singaporean core, thus weakening the sense of national and civic solidarity that needs to be the foundation of citizenship obligations and care for one another.

In the near future, a highly divided society may become disenchanted, as many feel excluded from Singapore’s success story for different reasons.

[related_story]

Disenchantment exacerbated by systematic elitism

This future disenchantment can also be exacerbated by systematic elitism.

Since the 1990s, the balance in Singapore-style meritocracy has shifted away from egalitarian values towards elitist ones. This is especially true in the way that talent is managed for political and public-sector leadership.

Photo via Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s Facebook page.

Photo via Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s Facebook page.

Salaries of civil servants and ministers

The government started to advance arguments in the 1990s to justify a proposal to benchmark the salaries of ministers and high-ranking civil servants to the average salaries of top earners in the private sector.

Significantly higher private-sector-like salaries were designed to help minimise financial ‘sacrifice’ and attract a future stream of talented young Singaporeans into public service, perhaps even encouraging the more entrepreneurial Singaporeans to bring their outlook and skills into the public service, which had clearly become rather technocratic following founding father Lee Kuan Yew’s more heroic generation of leaders.

The government also justified these salary proposals as a way of minimising corruption, since the opportunity cost of getting caught is heightened.

However, even if the realist view about people’s fundamentally materialistic motivations were difficult to challenge, the multi-million-dollar salaries have remained controversial.

Many Singaporeans have expressed much discomfort in the way public service motivations have now come to be equated with the ‘profit motive’ of the private sector.

Indeed, Shamsul Haque, a professor of public administration, observed that Singapore adopted market-based reforms ‘most enthusiastically’ to reinvent its governance in the neoliberal global context.

Inequality and political change

It is difficult to predict whether inequality would be a sufficient factor to bring about political change in the near future.

Political scientist Meredith Weiss noted that those hardest hit by economic dislocation – Singapore’s poorest, least adaptable, and migrants – are likely to be the least able to voice their interests through new technologies and modalities of engagement or to vote.

In any case, even as online space opens up more possibilities for critical engagement that can have an effect on the outcomes of general elections, the PAP government has put in place several co-optive institutions and constitutional innovations, as discussed earlier, that severely limit the possibility of electorally unseating the PAP in the near future.

Top photo from Tan Chuan-Jin's Facebook.

Content that keeps Mothership.sg going

? vs ?

You're on the MRT. Do you read or surf?

Why not both??

⛔?

Life's a beach sometimes but these girls really shouldn't be in swimwear...

?

Have a little money but can't help being kinda lazy? You can still invest using this.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.