Kwame Anthony Appiah is a law and philosophy professor at the New York University, and also an internationally-respected scholar on multiculturalism, race and identity politics.

He also happens to be personally quite qualified to discuss these issues, being the eldest child of one of Britain's first reported "inter-racial society" marriages (he has a British mom and a dad who is from Ghana). And after spending years both in Ghana and England, he now teaches in the U.S..

But we're telling you about him because of a 2,539-word essay he wrote that was published in American monthly news magazine The Atlantic about the hottest movie of the moment — the Hollywood box-office hit set in Singapore: "Crazy Rich Asians".

And as you might know, many, many, many people have raged, complained and been deeply upset and offended by the film's lack of adequate ethnic representation:

But Appiah's piece does not directly participate in this debate — he spends all of a paragraph outlining the unhappiness that exists against the film, concluding, somewhat, that book author Kevin Kwan never intended to cover Singaporeans of all ethnicities and cultures.

Instead, he takes a different tack, delving into a til-now-undiscussed (as part of this ongoing debate) aspect of Singapore's multiculturalism and representation: our country's unique ethnic policies, which he describes on the whole as a "bold experiment in ethnic engineering".

Here are the points he makes in "Crazy Rich Identities":

1. S'pore's commitment to integration is NOT a commitment to assimilation

via Getty Images

via Getty Images

Appiah notes, in what may stun American readers, that Singapore has top-down approaches to "enforcing" the mixing of races, like the Ethnic Integration Policy for HDB flats that imposes the quota of homes that can be sold to people of specific races.

[related_story]

Despite this, the government has always defined itself for its multiracialism — this quality is stressed right down to the words of our pledge, he argues:

"... regardless of race, language or religion..."

He believes the notion of race, language and religion being fault lines instead of reasons for unity stemmed from the two 1964 race riots, which, in his words, would have made the 'diversity as a source of strength' argument "a hard sell".

"Race, language, and religion were considered the three lethal fault lines. The question was how to stabilise them."

The calculation the late Lee Kuan Yew and our first generation leaders made, Appiah observes, is that Malay and Indian families would be hostile to the state if the 76-per-cent-majority-Chinese state was hostile to their heritage.

This brings us to...

2. The trouble with simplifying the breakdown of our races too much into the CMIO system

Photo via IPS Commons

Photo via IPS Commons

The Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others system is something we know so well we don't often think about it — but yet, it's a source of great intrigue for Appiah.

First of all, he notes it was instituted "for government purposes" back in 1965, observing the complexities and sensitivities our leaders considered in various policies:

- The decision to use the colonial language as the official language of government to prevent ethnic conflict — this came with a double bonus of helping to boost Singapore's role as a trade hub: we guess it did help.

- Malay was adopted as the national language, to respect the status of Malays as the first ethnic group of residents here — this meant our national anthem and military parade commands were also in Malay.

- Apart from learning English as our first language, all of us had to learn at least one other language — the one of our own ethnicity, typically.

These moves, Appiah notes, may on the surface seem like a dream, or again in the 64-year-old's own words, "crazy woke". But the point he makes is that Singapore's approach to this is not done with the intent of accommodation, but instead driven toward "entrenchment".

Appiah highlights the following complications that have over the years since arisen:

- Not all Indians are Tamil-speaking, just like how not all Chinese come from Mandarin-speaking families — many speak Hindi, for instance, and Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese and Hakka, respectively — but yet, this bilingual policy renders them unable to speak with their elders, who typically only speak/spoke a few (non-English) languages.

- Singlish is also discouraged in official use and in multiple language use campaigns too.

- People are increasingly marrying across CMIO lines, i.e. the number of interracial marriages in Singapore has gone up by a lot over the years.

"In short, it’s not the language you or your ancestors actually spoke but the identity the state has settled on for you that determines which language is yours. There’s no denying that the CMIO system reflected existing ideas about ethnic identity in Singapore: If it hadn’t, it would not have worked at all. But it entailed a radical simplification of a highly complex ethno-linguistic reality."

3. The tremendously high price of making a passing racial/religious slur

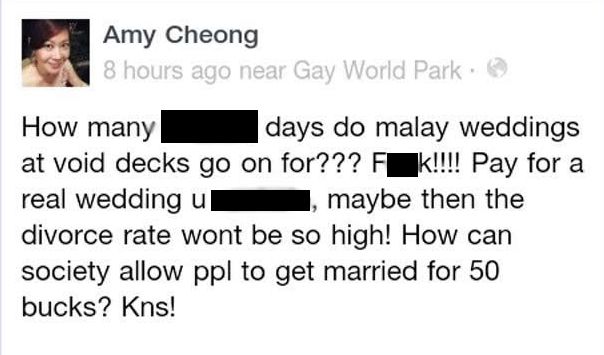

Amy Cheong's inflammatory 2012 post that eventually drove her to Perth. (File screenshot)

Amy Cheong's inflammatory 2012 post that eventually drove her to Perth. (File screenshot)

Appiah highlights the 2012 case of Amy Cheong, an NTUC Assistant Director who was fired from her job when a defiantly anti-Malay racist rant she posted on Facebook (raging against a wedding held at her void deck) went viral, got reported to the police and stirred up a visceral fury among thousands of Singaporeans.

He cites the Sedition Act, which bars people from "promot(ing) feelings of ill-will or hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore", calling it a "potent prohibition". He notes also that Cheong got off easy compared to a Christian couple who were in 2009 jailed for sending out mailers claiming Islam and Catholicism were false religions.

There is also the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act.

More examples: the preachers who were barred from entering Singapore because they were known for incendiary comments and teaching — both Muslim and Christian, by the way — and also a minister in charge of Muslim affairs, who places great scrutiny on Muslims at risk of self-radicalisation.

"There’s a complex bargain here: If the state helps protect ethnic identities in Singapore, it also polices them."

And another problem with that is...

4. As flawed as Singapore's system is, it may be the only plausible one right now

Appiah opens this point with the observation that the late LKY's speeches had evolved over the years from focusing on values and aspirations to policies, because the government-created idea of the "Singaporean Identity" had, to Appiah's mind, stabilised.

"If the state he created was watchful and intrusive by the standards of a Western liberal democracy, it had also convinced most of its citizens that they were engaged together in a meaningful national project."

But, he argues, this veneer of happiness and harmony obscures what he deems to be a "state-imposed silence about inter-group difficulties" — he believes racism definitely continues to exist among many Singaporeans.

And he concludes with this insight we can all chew on:

"The truth is, to set out to govern identities is to set out to govern the ungovernable. Whatever the state does, ordinary people will ignore the boundaries it sets...

The point isn’t that the government of Singapore should ignore the ethnic and religious identities of its citizens. But it will have to acknowledge that it’s no longer just the society that’s multiracial: more and more of its citizens are, too."

Fascinating.

But perhaps the true hallmark of how good Appiah's essay has been received can be seen by the sheer variety of Singaporeans who have shared the link on their Facebook pages (here, here, here and here).

Pretty unifying, as it turns out.

And now, for some stories that are actually about "Crazy Rich Asians":

Top photo of Anthony Appiah by David Shankbone; screenshot from Crazy Rich Asians trailer

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.