What was a successful campaign in Singapore's history?

Singapore launched a "Stop at Two" campaign in 1972 to limit the number of children that families were having.

It was wildly successful.

Fertility rates dropped after the campaign’s implementation and it was even reported that large families felt ostracised for going against the message.

The data shows Singapore’s low birth rates have persisted ever since then.

What policy is Singapore pushing for these days?

Singapore is desperately trying to reverse the decline in birth rate.

Singaporeans are actively encouraged and incentivised to have more children.

However, the policies of curbing procreation and encouraging it are not symmetrical.

In a nutshell: Curbing procreation is more direct and blunt, with the interventionist state able to pull many more levers that involved penalties, while encouraging procreation is more oblique and requires nudging citizens in the right direction.

1. Before "Stop at Two" campaign

Before 1970, the government’s family planning was going well.

The National Family Planning Programme (NFPP) was rolled out in 1966 after the government set up the Singapore Family Planning and Population Board (SFPPB) in January 1966.

Its goal was simple: To reduce the number of births to achieve zero population growth. In essence, having the same number of births and deaths.

The NFPP consisted of social campaigns, such as “Plan your family” and “Singapore wants small families”, and contraceptive services made available via government-run clinics.

In short, the government made it desirable to have smaller families, without actually specifying what the ideal number was.

Crude birth rate dropped from 28.3 to 21.8 births per 1,000 residents between 1966 and 1969.

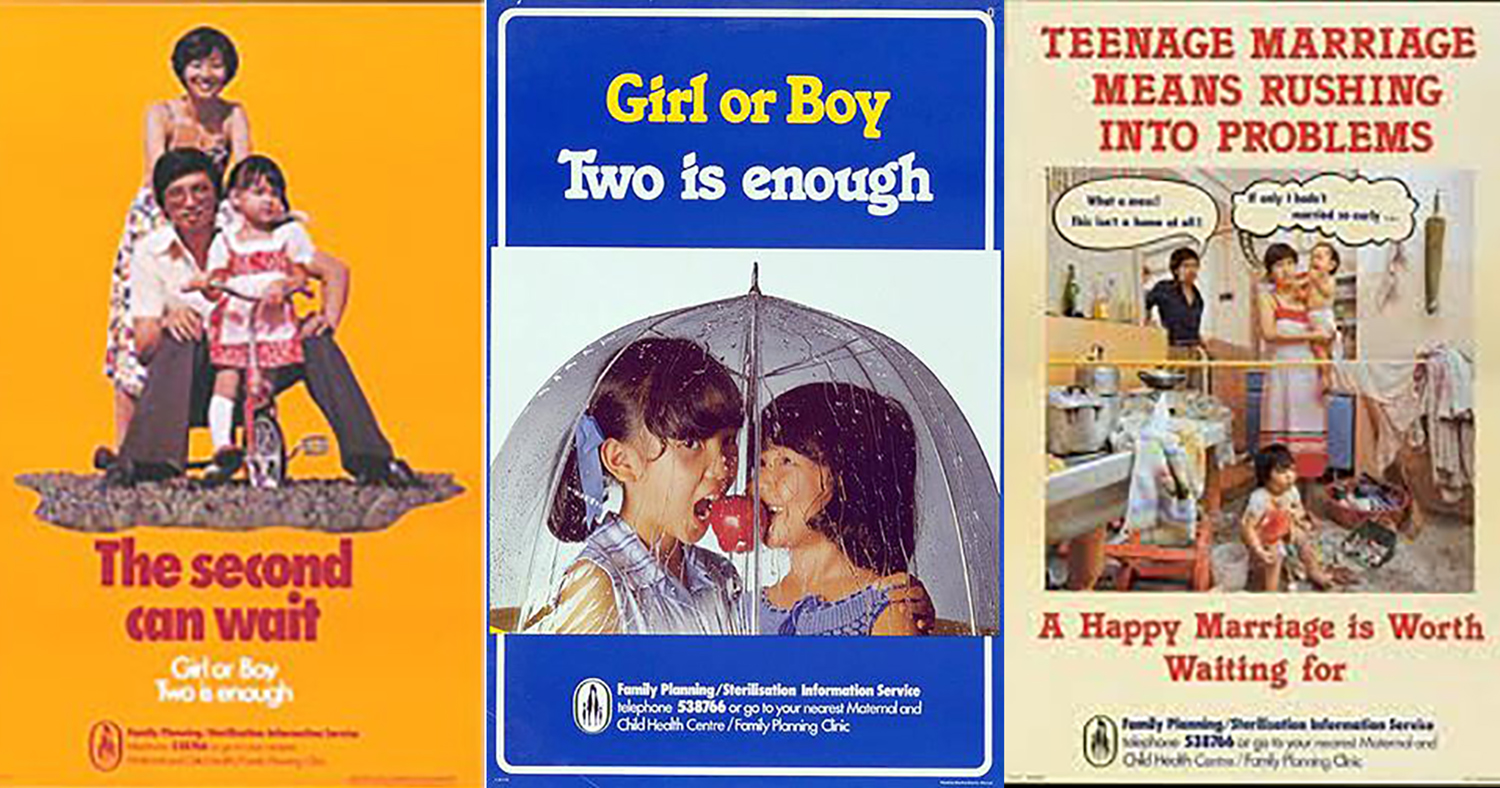

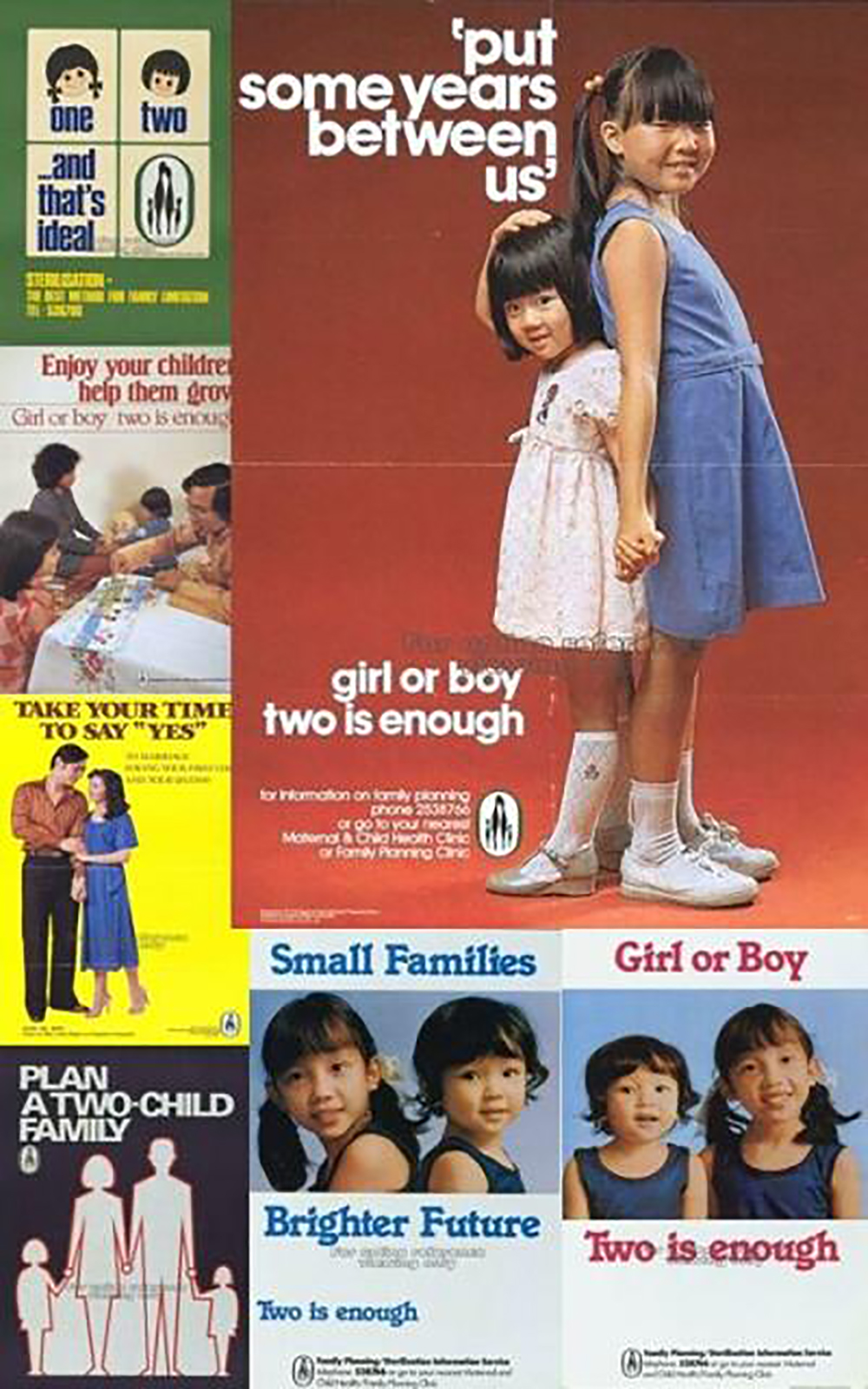

1978 Family Planning campaigns.

1978 Family Planning campaigns.

2. How two children became the ideal number

Then came the boomers.

From 1970, the postwar baby boomers started getting married and having children.

By then, the number of women in the reproductive age group doubled compared to five years prior.

Additionally, many families still wanted to have three children or more.

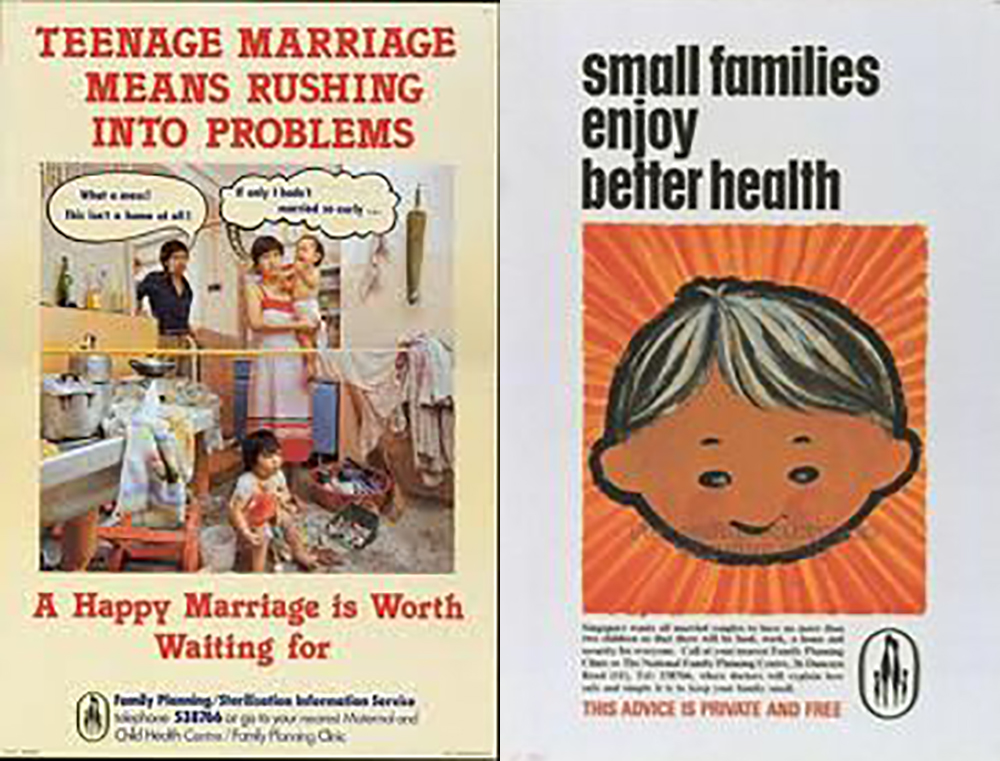

Large families were common after the war. Via NAS.

Large families were common after the war. Via NAS.

This caused the crude birth rate to rise from 22.1 births per 1,000 residents to 23.1 births per 1,000 residents.

Secondly, a small but significant portion of the female population -- about 30 percent -- was not taking on the family planning services provided by the government.

According to then-Health Minister Chua Sian Chin in 1972, these included the "low-income, high parity (women who have had multiple births), and older age group of women".

This prompted the authorities to include a limit -- two children -- in their campaigns, a change from "small families" messaging in prior campaigns.

The number "two" was not arbitrary.

It was based on calculations that this limit will ultimately result in the population reaching the replacement fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1 children.

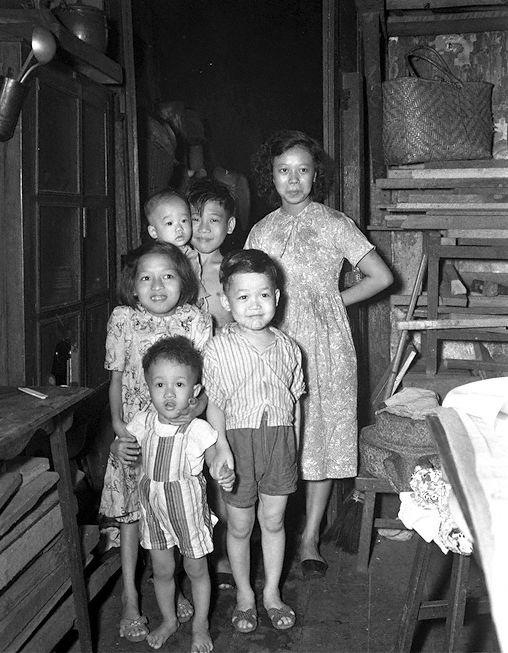

Campaign posters also featured two girls in a bid to normalise having daughters instead of sons.

3. "Two is Enough"

The two-child policy ran from 1972 to 1987, a total of 15 years.

Throughout that time, the campaign ran with slogans such as:

• "Small families, brighter future – Two is enough",

• "The more you have, the less they get – Two is enough", and

• "The Second Can Wait; Boy or Girl, Two is Enough".

[related_story]

The messaging was that all families, especially those who are less educated or are from lower income groups, should have two or less children.

"While the better educated young women have one to two children, the lesser educated young women have more than three children, though they do practise family planning."

- Then-Health Minister Chua Sian Chin in 1972.

Since the lesser educated or lower income people tended to have more children, the reason for pushing this message to them was that having fewer kids meant being able to allocate more scarce resources to them.

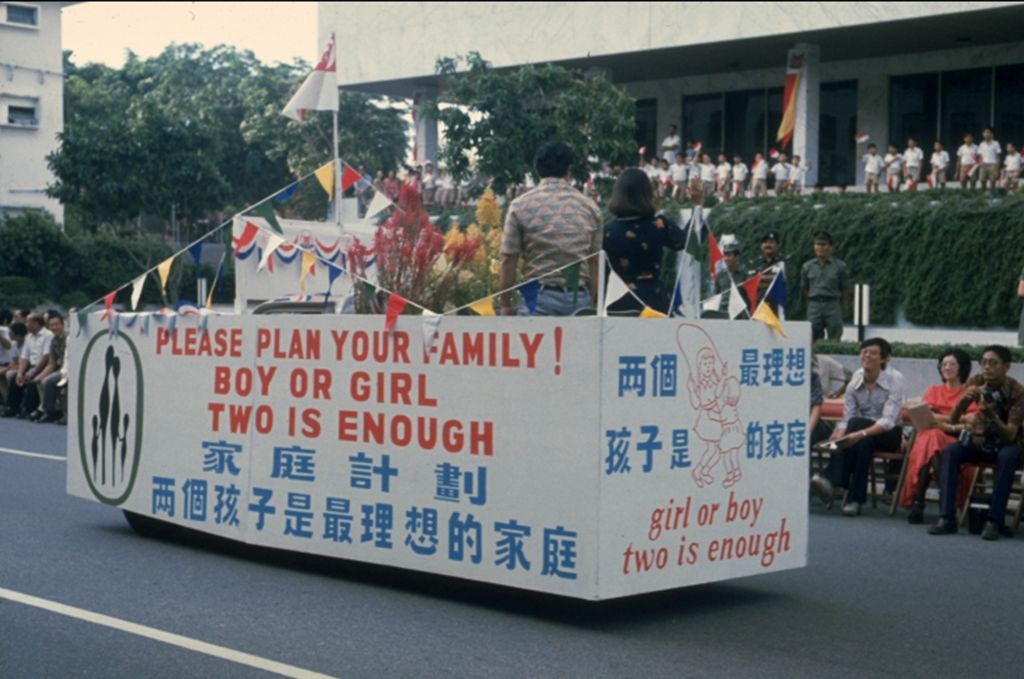

A float with family planning messaging on it.

A float with family planning messaging on it.

4. Discouraging multiple births

Aside from a sustained media campaign by the Information, Education and Communications (IEC) Unit of the SFPPB (Singapore Family Planning and Population Board), the government also rolled out several disincentives to discourage people from having multiple births.

These included:

- Reduction of income tax relief to cover only the first three children.

- Government hospitals increased their fees for giving birth.

- Waiver of birth fees and other fees for the fourth child if either husband or wife underwent sterilisation.

- Reduction of paid maternity leave from three to two confinements

- Lower priority for larger families who are waiting for Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats.

Stop At Two campaigns from 1970 to 1986.

Stop At Two campaigns from 1970 to 1986.

The Abortion Act was amended in 1974 to allow for easier abortions.

Before that, a woman who wanted an abortion needed to seek approval from an 11-member board called the Termination of Pregnancy Authorisation Board. This layer of approval was scrapped in 1974.

The Voluntary Sterilisation Act was enacted also in 1974 to allow women to undergo sexual sterilisation for non-medical reasons.

Parents who undergo sterilisation received reimbursement for their delivery fees and priority in school enrolment.

5. Why was "Stop at Two" so successful?

The Stop at Two campaign was a roaring success.

The messaging was so pervasive that society even began stigmatising big families.

According to an account submitted to Singapore Memory Project, mothers who insisted on having more than two children were considered "uncooperative" and "chided by doctors, nurses, and hospital attendants".

Whenever we took our three children for an outing at public places, we noticed the disapproving look on people’s faces. Such was the effectiveness of this campaign in slowing down the growth of our population. It was a roaring success.

- Mr Salleh Sariman, a father of three.

By 1976, the total fertility rate peaked at 2.11, and the effects of the Stop at Two campaign began to show in earnest.

The following year in 1977, the fertility rate started its decline, dropping to 1.82.

Pictured are a mother and her three children during a time when the government actively persuaded parents to stop at two children. Big families faced stigmatising during that time. Image via Singapore Memory Project.

Pictured are a mother and her three children during a time when the government actively persuaded parents to stop at two children. Big families faced stigmatising during that time. Image via Singapore Memory Project.

However, disincentives and public messaging weren't the only things that contributed to lower birth rates.

The Two-Child Policy coincided with Singapore's push to become a manufacturing hub.

As more women received an education and joined the workforce, a direct correlation was a decrease in birth rates.

Transferring people from sprawling communal living to small HDB units also caused people to rethink their family size.

Big extended families were no longer feasible in small flats.

Socio-economic change and urban development, coupled with a sustained family planning campaign, created the perfect storm to kick-start the irreversible trend of declining birth rates.

In Singapore's case, the decline was perhaps more pronounced than many other countries in that era then.

Some unrelated but equally interesting stories:

How to train to be a ninja warrior, in your office

Watch a concert with your ears only at this Esplanade concert in the dark

Long-term care is one awkward conversation you must have with your parents

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.