Professor John N. Miksic of the National University of Singapore (NUS) is an archaeologist in Singapore.

His work refutes the common narrative that Singapore’s history started with the landing of Sir Stamford Raffles.

On Jan. 11, 2018, the American won the inaugural Singapore History Prize for his book, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300-1800.

The book entrenches Singapore’s position as a maritime emporium since the 14th century. It is a part of local history that started gaining traction since 2014.

It is also a culmination of 28 years of work sifting through the soil here.

Who is Miksic?

The 71-year-old archaeologist has worked in Singapore for 34 years.

He is almost like Singapore's version of Indiana Jones -- a term he doesn't mind at all because it "glorifies the profession, gives it some sort of dignity".

Miksic is quick to point out that unlike Indiana Jones, archaeologists aren't treasure-hunters.

Instead they are interested in how excavated treasures can tell stories of the lives of people from a long time ago.

Ended up in Malaysia

Growing up on a farm near the Canadian border, Miksic originally planned to study the origins of the Inuit people in Siberia.

But his time with the Peace Corps took him to a whole other world -- Malaysia, which he spent four years there from 1968 to 1972.

Miksic explained:

"[The Peace Corps] said, 'No, you come from a farm. We want to help the Malaysian government set up a Farmers Cooperative.' So they sent me to the Bujang Valley in Kedah."

The Peace Corps taught Miksic the Malay language and made him go to the foot of Kedah Peak (now known as Gunung Jerai).

There, he helped local farmers develop an irrigation system and used his experience as a farmer to encourage them to join a Cooperative.

When he was there, it was the ancient ruins that caught his eye.

"There were dozens of sites with old stone temples and Chinese pottery from a thousand years ago but nobody there knew anything concrete [about the ruins]."

The locals in Kedah told Miksic stories about an ancient raja (king) and his empire, and that was what hooked him into the early history of Southeast Asia.

[related_story]

Singapore's first archaeology dig

After 1972, Miksic went back to the United States where obtained his PhD programme at Cornell by excavating an ancient Chinese fort, Kota Cina in Sumatra.

In 1979, Miksic was posted to Bengkulu (previously British Bencoolen) where he worked as a Rural Development Planning and Management Advisor for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

He then went on to Yogyakarta in 1981 where he taught Archaeology at Gadjah Mada University.

Three years later in 1984, he received an invitation from Singapore's National Museum to conduct a test excavation on Singapore soil, especially since there has never been one before.

Miksic said:

"They said Fort Canning should be a good spot to look because there was the Malay Keramat Iskandar Shah. So, they said, 'This is the mythical tomb of the last of the five rulers of Singapore. Whether or not it's true, it's a good place to check out.'"

Keramat Iskandar Shah. Image via Wikipedia.

Keramat Iskandar Shah. Image via Wikipedia.

NSFs participated in digs

The first archaeological dig, and most other forthcoming digs, was a hodgepodge of rather disparate resources.

Funding came from the private sector, such as Royal Dutch Shell Petroleum, and manpower was supplied via the museum staff and, most bizarrely, full-time National Servicemen (NSFs).

Misksic said:

"These were National Servicemen who were on punishment duty because they had gone AWOL (absent without official leave) but they actually enjoyed it. They actually found this was somewhat useful. Even they (who were not trained in archaeology) could see the significance of this dig."

Fort Canning Hill did prove to be a treasure trove of artefacts dating back to the 14th century. The 10-day excavation yielded Chinese pottery, Song and Tang Dynasty coins, glass beads, and ancient jewelry like this below:

Earrings and gold armlet with the design of Kala, the Hindu god representing time and destruction, believed to be from the 14th century. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Earrings and gold armlet with the design of Kala, the Hindu god representing time and destruction, believed to be from the 14th century. Photo by Joshua Lee.

But what was more shocking to Miksic was that tales of ancient Singapura from a bunch of Malay myths were actually not too divergent from the truth.

Miksic went on to lead more than 10 digs along the Singapore river from 1987 when he settled down here.

But these were all rescue digs -- hasty affairs done quickly whenever a building is being knocked down or a plot of land was redeveloped.

Singapura and the Chinese empire

The team found more pottery, more traded items like glassware, jewelry, foreign coins, and an exceptional amount of Chinese artefacts that point towards a close relationship with the Chinese empire.

Chinese artefacts such as pottery and stoneware gave the team important clues on how Southeast Asian cities and China viewed each other.

Miksic said:

"Which ones have the same types of Chinese ware? They must belong to the same network, but do you find the same kind of things in say, Ang Kor, than you find in Singapore?"

China was known to develop customised goods for external markets, such as Southeast Asia, and the Indian Empire, indicating that they had knowledge of the cultural demands and tastes of their customers in these markets.

Gold dish with a pair of mandarin ducks exported to the Middle East, found on the Tang Shipwreck. Image by Joshua Lee.

Gold dish with a pair of mandarin ducks exported to the Middle East, found on the Tang Shipwreck. Image by Joshua Lee.

The Changsha bowls retrieved from the Tang Shipwreck are perfect examples. These had drawings of Middle Eastern faces and pseudo-Arabic calligraphy clearly tailored for the Middle Eastern market. You can see them now on display at the Asian Civilisations Museum.

As the digs went on, the team began to uncover a clearer picture of 14th century Singapura, a port city right smack in the middle of a maritime trading route, where goods -- both raw and finished -- came to change hands, and where a multi-ethnic population lived under the governance of a local chief.

Miksic advocates that the archaeological findings should be used to solidify the idea that people of different ethnicities have been living here together for the longest time, with a hybrid culture -- possibly the precursor to the Peranakan culture.

Miksic said:

"They had lived together here for hundreds of years before the British came. I think there was already a hybrid culture, because we found all these glass beads on Fort Canning, which are well known to be part of Peranakan culture."

The Headless Horseman. a lead statue excavated at Empress Place. It's thought to be Javanese in origin. Notice the 'wayang kulit' design. No other lead statues have been found in Southeast Asia. Image by Joshua Lee.

The Headless Horseman. a lead statue excavated at Empress Place. It's thought to be Javanese in origin. Notice the 'wayang kulit' design. No other lead statues have been found in Southeast Asia. Image by Joshua Lee.

Public-private support needed

In March 2011, a breakthrough role-playing game, the World of Temasek, was launched.

In it, the player takes on the role of a citizen of Temasek, and learned more about ancient Singapura through explorations and interactions in the game.

World of Temasek image via Magma Studios.

World of Temasek image via Magma Studios.

World of Temasek (WoT) was augmented by actual interpretation gained from archaeological artefacts and designed to be as factually accurate as possible.

As far as history lessons went, WoT was by far one of the best and immersive experiences available to the public.

It was bankrolled by the government for seven years until the game was took down in March 2017 due to, among other things, a lack of funding.

The sad fate of WoT is but an example of the woeful lack of support given to archaeology.

Miksic said:

"We never had to pay people to excavate with us. It's always seen by a large portion of Singaporeans as relevant to their identity. We live on the same plot of land, we face some of the same problems today, we can learn a lot from (the people who were here before us)."

Yet, archaeology has received strong support from members of the public, despite a lack of funding.

There are a few private institutions -- Royal Dutch Shell Petroleum, American Express and Lee Foundation -- that continue to sustain Miksic's work.

But they are not enough to fund beyond that -- laboratory space, equipment, and higher education for Masters and PhD students, just to name a few things.

A visit to the NUS Kent Ridge-Fort Canning Archaeology Laboratory reveals room after room crammed full of artefacts with hardly much space for anything else.

Miksic's desk. All the rooms in the laboratory are filled with boxes of excavated shards, mostly incomplete. Image by Jiahui Wee.

Miksic's desk. All the rooms in the laboratory are filled with boxes of excavated shards, mostly incomplete. Image by Jiahui Wee.

Beyond that, central regulation and legislation have yet to catch up, for example in the area of artefact ownership.

Miksic said:

We still don't have a good system of who owns the things you dig up. Theoretically the government has first claim on objects that are judged to have relevance to Singapore's heritage, but there's no requirement for the owner to surrender them.

Even the basics like accreditation for archaeologists, and central coordination body for various digs and research are hard to come by.

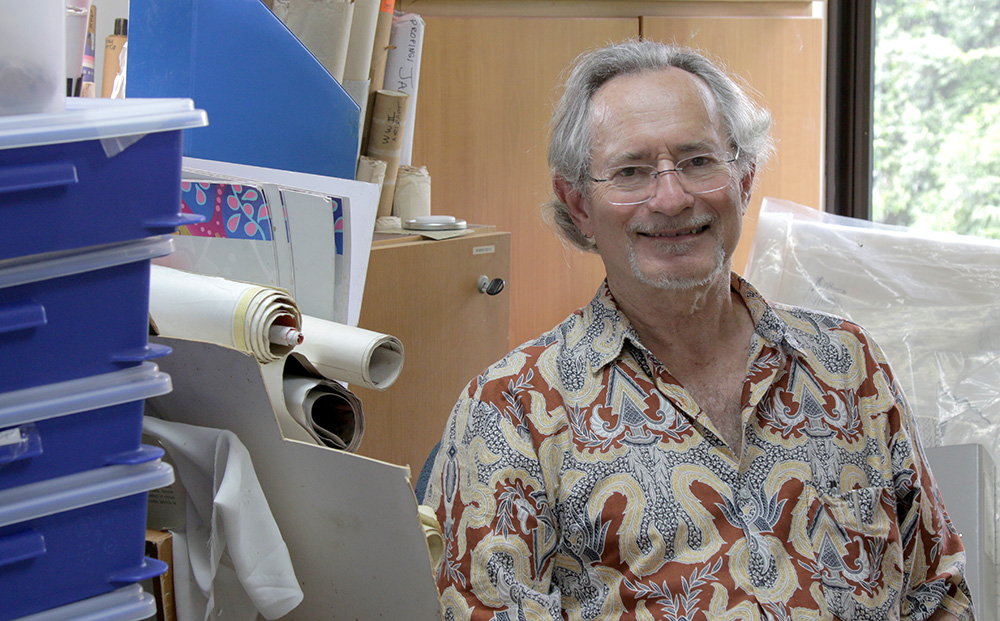

Miksic at his laboratory. Image by Jiahui Wee.

Miksic at his laboratory. Image by Jiahui Wee.

NUS Kent Ridge-Fort Canning Archaeology Laboratory

Situated on the highest point of Kent Ridge road and tucked away, like an afterthought, from the vast National University of Singapore (NUS) campus is a spartan two-storey bungalow.

The NUS Kent Ridge-Fort Canning Archaeology Laboratory.

The NUS Kent Ridge-Fort Canning Archaeology Laboratory.

Built in the 1950s by the Public Works Department (PWD) for British military personnel, the house had a vantage point of the western harbour and Straits of Singapore.

Today, it is home to the NUS Kent Ridge-Fort Canning Archaeology Laboratory, and instead of the western harbour, visitors are greeted by the Pasir Panjang container terminals.

"They'll be gone soon, and I'll have my view back," chuckles Miksic, who is the laboratory's resident archaeologist.

Professor John Miksic.

Professor John Miksic.

Things could change

However, there is hope that things will be changing.

The Singapore government recently announced the roll out of a new Heritage Plan blueprint this year, which would encompass four different aspects of national heritage: Places, Culture, Community, and Treasures.

Archaeology falls under the latter.

Under this new plan, more efforts will be expended to safeguard national treasures that are being excavated and introduce legislation that provide a stable framework for future archaeologists to work with.

As we end the interview, Miksic invited Mothership.sg to tour his tiny, cramped laboratory.

Rows and rows of shelves holding boxes of porcelain and stone shards line the walls.

Taken individually, these pieces are practically worthless on the market, yet seen as a whole, they are a painstaking reminder of the work Miksic and his team of archaeologists have done over the past decades.

Prof Miksic holding up portions of a stoneware bowl from an excavation site in Singapore.

Prof Miksic holding up portions of a stoneware bowl from an excavation site in Singapore.

Miksic is now 71 and desires to pass these on to the right hands. But who?

It took us 34 years to finally pay attention to what archaeology can offer us.

Let's just hope we don't have to wait another 30-odd years.

Top image by Jiahui Wee

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.