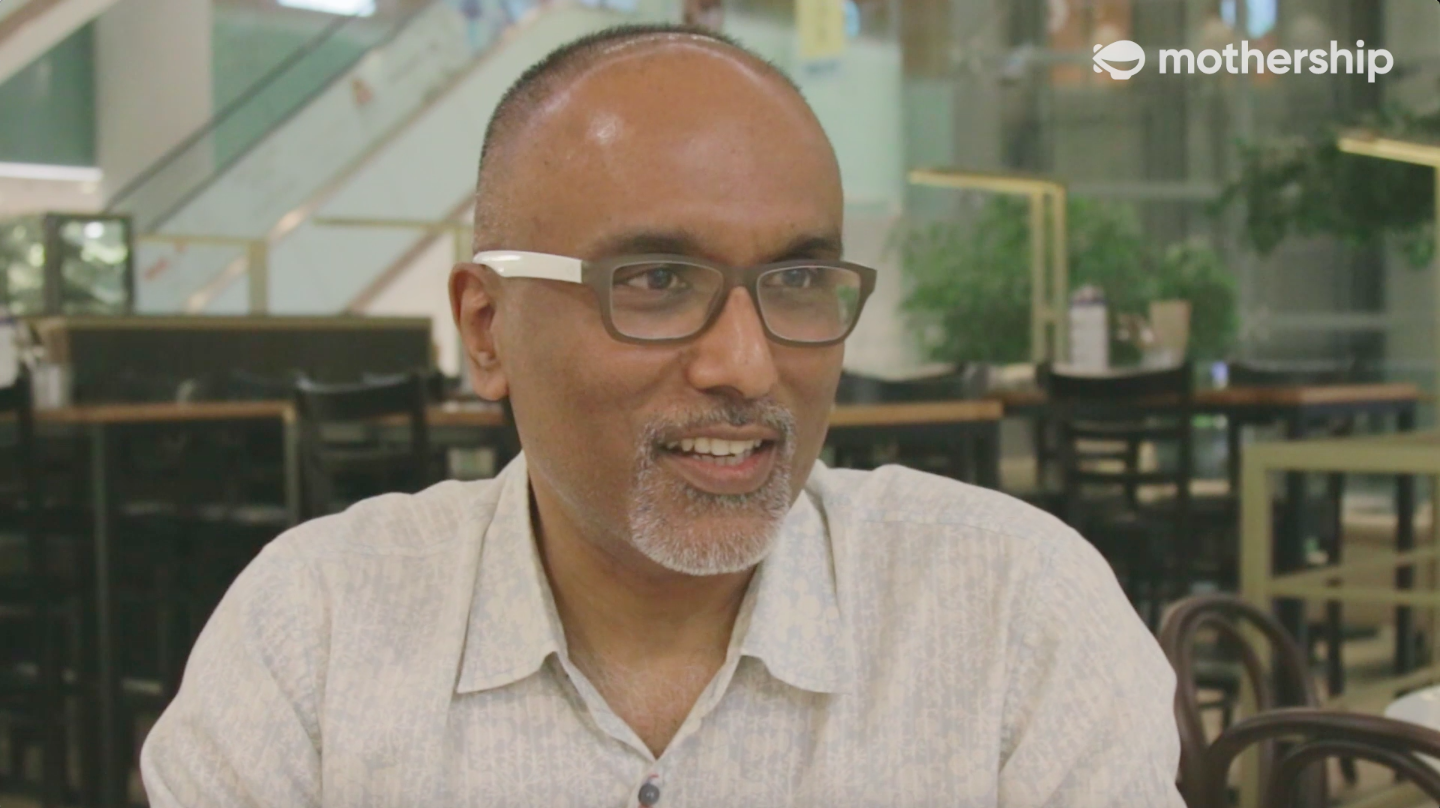

We can't quite refer to Cherian George as a political dissident or exile.

He hardly went through physical suffering, nor was he at any point arrested or jailed without trial.

Quite the contrary, George is a professor of media studies, a scholar in media and an internationally-respected voice on the intricacies of government-media interaction and press freedom.

These days, he lives and works in Hong Kong with his wife Zuraidah Ibrahim, a former top editor at The Straits Times (ST)-turned Deputy Executive Editor at the South China Morning Post, but somehow finds himself coming back to Singapore to visit every now and then, several times a year.

And so one fine day in August, he allocated us two precious hours of his rest time, having just flown in for a packed week of events.

When we met, it was almost as if he had only the time to check into his room at Orchard Hotel and put his bag down — as we apologetically walked him around the lobby and an adjoining mall, we decided the least we could do was to buy him coffee and truffle fries at a quiet, brightly-lit café we eventually settled at.

And we talked — about journalism education, the state of politics in Singapore, his take on where we are now — but one thing he was, and always has been, reticent about discussing too much is what happened to him in the years he lived here.

We won't blame you for not knowing him, though, if you only started following political news in Singapore in recent years — chances are, that means you will have missed the rather jarring series of events that put paid to his career — and well, life as he knew it — in Singapore.

How he was systematically pushed out of Singapore

Prior to August 2014, when George moved to Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU), where he now teaches, researches and writes, he was one of the hallowed draws of NTU's Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information — a name that also originated from an idea he first had.

NTU's communications faculty was at the time arguably seen as the course of choice for tertiary media education. George, who happens to be the same age as independent Singapore, was responsible for founding many of the initiatives that have made the journalism course the stand-out programme.

2009: Promoted without tenure

Five years into his decade at NTU, George was promoted from Assistant to Associate Professor in 2009. Back then, he was told he had done nothing wrong, and had met all the criteria for promotion and tenure, which come hand in hand.

But yet, he was promoted, but not awarded tenure — a very curious and also unprecedented move. He wrote in a blog post:

"As for why the university took the exceptional step of withholding tenure from a faculty member who it decided had earned promotion, I will only say that I was assured categorically that this had nothing to do with my research and scholarship, teaching or service, and also not because I had conducted myself inappropriately in any way."

Funnily enough, that year also saw George winning the Nanyang Award for Excellence in Teaching, the university's highest honour conferred to faculty members in teaching.

2010: Denied re-appointment as head of journalism division

George was informed that the Wee Kim Wee School's request to reappoint him as head of journalism, a position he had already held for a number of years, was denied by the university.

No academic reasons were cited for the University's decision.

2012: Rejected for tenure again, and this time it was final

The interesting thing here is it wasn't George's idea to re-apply for tenure. He was asked to resubmit his application, and he did, with documents from his 2009 promotion and tenure assessments, but these were at some point and unbeknownst to him redacted from his submission.

He was denied tenure for the second time.

[related_story]

2013: Academics protested second tenure rejection in anger

When news of this started filtering out in early 2013, his external reviewers, academics in other countries, spoke out angrily against the university's decidedly flimsy claim that the approval of tenure applications are a purely a peer-driven academic exercise:

As a reviewer, Cherian George's tenure case was watertight - must be all about politics and repressing academic freedom. Shame and scandal.

— Professor Karin Wahl-Jorgensen (@KarinWahlJ) February 25, 2013

George decided to appeal the rejection. As you might have guessed, this final appeal was rejected too.

His contract with NTU ended in Feb. 2014 with no possibility of renewal.

And to this day, four and a half years on, NTU has said nothing in its own defence or in response to questions posed to it about George's case.

Though Cherian eventually revealed the possible reasons on why he was denied tenure in a December 2014 blog post:

"Only political and no academic grounds were ever cited by the university leadership for this 2009 decision. I was told of a 'perception' that my critical writing could pose a 'reputational risk' to the university in the future."

So why him?

To understand the "critical writing" George is referring to, we need to trace his journey as a political commentator that started from his earlier years at ST's political desk.

It might be relevant to point out this little nugget from ST in September 1999, while George was still working at the paper — it featured this quote from the late Lee Kuan Yew:

"... you can denigrate the prime minister at will — whether it's Catherine Lim or Cherian George — and they succeed in undermining the standing of the prime minister — where do we go from there?".

This, by the way, is the novelist Catherine Lim in the "Catherine Lim Affair". She was sternly rebuked by the government for her commentary in ST in 1994, in which she suggested that then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong's promise of a more open and consultative style of government had not been kept.

And George was mentioned in the same breath — a clear reflection of how Lee had viewed his writing and commentary on politics.

His talent for critical thinking on Singapore politics was refreshing, as reflected in his first book, Singapore: The Air-conditioned Nation, where he wrote eloquently about "the politics of comfort and control".

The 25 essays in the book he wrote "for all who call Singapore home" were lucid and incisive. For example, one commentary about OB (out of bounds) markers took aim at the government's approach to freedom of speech and expression — charting the various laws and restrictions it enacted in the 1990s.

Those who were following politics in 2005 might also recall a two-and-two exchange that the journalist-turned-academic George had with PM Lee Hsien Loong's then-press secretary Chen Hwai Liang.

It involved an essay George wrote for The Straits Times, adapted from a scholarly article he wrote about what he terms "calibrated coercion" — an approach he believes the PAP uses through implementing restrictive, excessively-widely-defined legislation and behind-the-scenes actions they take against parties (be they opposition or academics or indeed, anyone who speaks up against their policies and practices).

His commentary was seen as sufficiently credible to draw two rounds of responses from the government.

And this is the background of his career in Singapore and how it unceremoniously ended, something we feel is important enough to spend time telling you about in order to truly understand the significance of the work George continues to do — even though he is all the way in Hong Kong.

Then why bother?

Image of cover courtesy of Pagesetters

Image of cover courtesy of Pagesetters

After all that, an arguably brilliant mind like George's (and we're not just saying this — he does have degrees from Cambridge, Columbia and Stanford) could have just moved on from Singapore and focused his efforts on contributing to journalistic and academic media discourse in Hong Kong.

But curiously enough, he is no quitter, and it's clear from our conversation with him that for some odd reason, he truly still is passionate about this tiny city-state.

This lends itself to his latest book, Singapore: Incomplete.

At first glance, and perhaps at initial reading, one realises it isn't really about the media, or press freedom, or any of George's particular usual academic foci. It is also thinner than all his previous ones — scholarly tomes on the state of press freedom, media-government relations and political communication around the world.

"One thing that I guess was different about writing this book compared with, say, longer things I have written... is that with this book I had a clearer sense of who I was writing for."

It's not addressed to the government, that's for sure — George declares "that would be a total waste of my time because there is no way they would want to... I will just say that because I think there is a mental block. I don't see the current leadership as persuadable to that way, on any of the points I raise".

But at the same time, it certainly isn't simply an outlet for his political rambles. From the chapters George snuck us in the course of writing the book, we see that it is kind of a letter in parts — to Singaporeans who aren't sure what to make of what's happening in these times; the Singaporeans who think the ruling party is doing a decent job on the whole, but they might be getting a bit arrogant with the seemingly-unfettered power Singaporeans handed to them in 2015; even the Singaporeans who earnestly want the PAP to stay in power.

From race to LKY's fundamental policy missteps

On the topic of race, for instance, George devotes an entire essay to making the point that we need to think of racial and religious diversity as a source of strength for Singapore. Unfortunately, he opines, our leaders have been largely cautionary in nature in their public statements, urging Singaporeans to band together and not let our diversity become a threat:

"If the very strong official narrative is that race and religion are fault lines, it's natural that there are some Singaporeans who will misinterpret this as a signal that we will be better off if we were homogenous. I mean I don't think that's what the government is saying, but that is clearly the unintended consequence of that official rhetoric."

For instance, he says the confrontation of and forging of a national identity must take into account three groups of Singaporeans:

- The group that feels everyone should be homogeneous and race blind — the difficulty with doing this is that it ends up becoming the identity of the majority, which is Chinese;

- The group who feels strongly about their race, religion and culture, and who isn't comfortable with giving them up; and

- The racists.

And these three groups of people, in his view, all need to have the humility to acknowledge that they aren't totally right, and may need to compromise some of their beliefs or positions in order to forge this common identity we all seek.

On the topic of policy missteps, George flags two key ones — ministerial salaries and the office of elected presidency — as truly being the PAP's (LKY, in particular, actually) fault, especially because they pushed these policies through despite clear, comprehensive and reasoned feedback and disagreement from academics and members of the public when they were first being discussed in the 1980s.

"When it comes to the presidency and ministerial pay formula, the decision makers at the time must be blamed, right. Because there were many Singaporeans telling them what would go wrong and they were proven right...

All these arguments were there and they were just completely brushed aside (by LKY). so of course the government deserves to be criticised for (these errors)."

He added that the critique on these two policies came from parties supportive of the ruling party, too, not just regular critics or the political opposition, which is what made them even more striking for him.

"So when the government makes mistakes like this that show so clearly a "we know best" attitude, when in fact there were many well-meaning, wise responsible criticisms offered, then there's something systemically wrong with the way we take positions in Singapore."

In the face of the problems we now have to deal with, and the unhappiness we feel as a result of these two policies, however, George notes that the ruling party still has yet to acknowledge their folly in enacting them.

"I think there's a bigger issue here, right? The bigger issue is how do we assess, you know, very clinically and objectively, the institutions and norms and habits that we have inherited from the LKY years, and where necessary make bold changes to suit new times."

There still is hope... in the 5th generation of leaders

George has no doubt whatsoever in his mind that the ruling party will pay no heed to anything he says in the book. He also doesn't think he will see any meaningful change in them — to the tune of "plural politics, a reformed PAP and so on" — in the course of his working and politically active lifetime.

He says he isn't writing for the solidly anti-PAP crowd, either:

"The main reason is that I think there is an audience that I really do want to communicate with. As a result of the 2015 election, right, it's quite clear that anyone who wants positive reforms in Singapore have to recognise the fact that the majority of Singaporeans think highly of the PAP. Full stop. Nobody can run away from that. So that's one reason why I don't write this for the solidly anti-PAP types. I simply feel they are the wrong audience."

Now, it can be hard to imagine that among Singapore's millennial generation live about 30 or so individuals who can form the leadership with the gumption to make the change our country needs, the way the late LKY and his lieutenants rose to the occasion in the 1960s.

But George is confident that statistically, they must exist, and that they will step up.

"What the PAP and their supporters celebrate today is the creation of a small band of exceptional young Singaporeans. Lee Kuan Yew and less than 20 other people. So I asked myself, is it reasonable to hope that in Singapore today, among teens among 20-somethings and 30-somethings, that there are 20 Singaporeans with exceptional intelligence, ability, sense of public service, empathy, and conscience, to make Singapore what it can be? Yeah, of course I have hope! You can't find 20? Please!

... And so if I think about the 5G leadership, yes, I am hopeful. I am hopeful because to me, the reasons for change are so compelling, right, that you have to be extremely stupid not to recognise that over the long term that change must come. And I don't think Singaporeans are stupid, full stop. You'd have to be stupid to think that reforms are not necessary over the long term, and I just don't think Singaporeans are that stupid."

And it is they in particular he hopes will read his book:

"I do think that PAP supporters would include many, many Singaporeans who would understand the need for change, who would understand the need for reform. And it's really, mainly to them — that's the main audience that I had in my head as I was writing this. Including younger Singaporeans who will end up as leaders in the PAP and so on. So the 5th generation."

(Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the official positions of George and Zuraidah. These errors have been corrected.)

(Also, Jeanette is a former student of George’s.)

Top photo by Ilene Fong

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.