In this preview of a chapter from his forthcoming book, media academic Cherian George argues that Singapore’s multiracialism would have been better off if the government had kept the presidential election open for Tan Cheng Bock to contest, or abandoned the elected presidency completely and reverted to the old system of a ceremonial head of state.

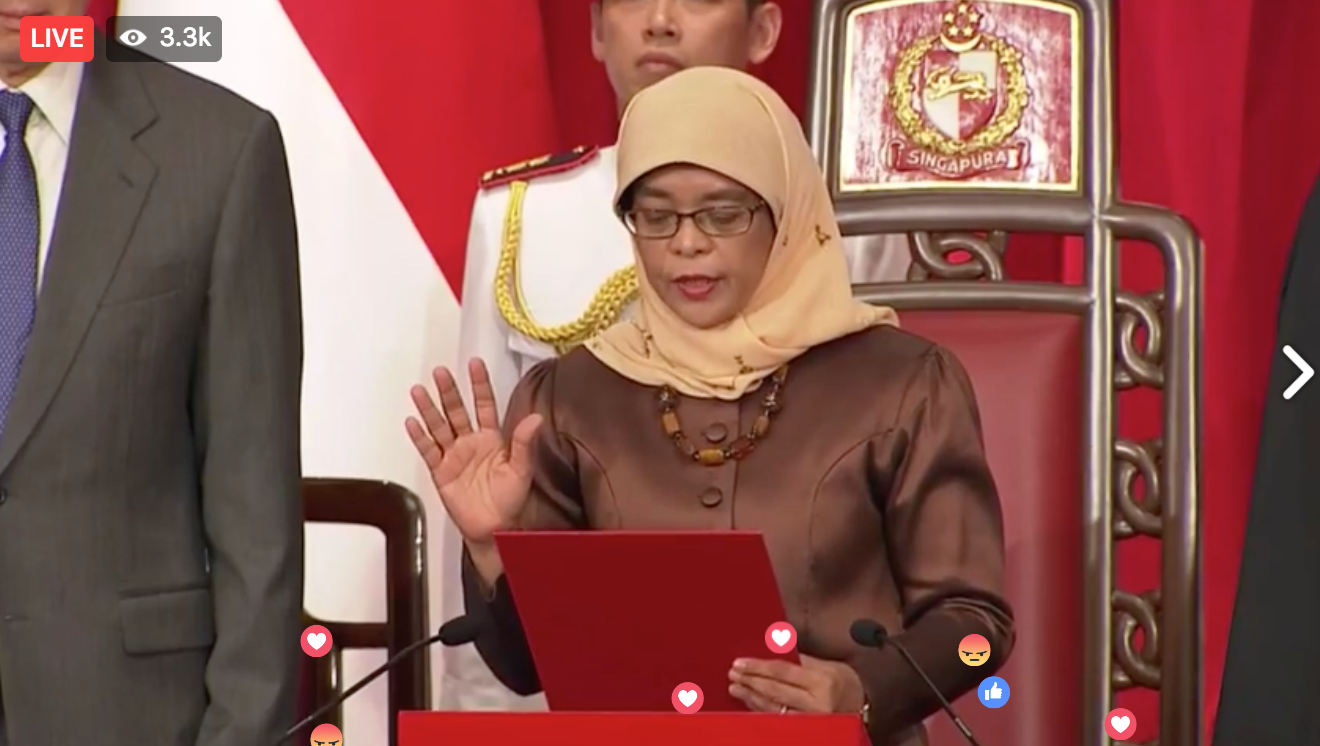

Prediction: Halimah Yacob will make a marvellous president. I’ve barely met her and we’ve only exchanged pleasantries. But what I know of her, I respect. And what a powerful symbol for equality. Singapore’s first female president; the first from a Malay background since 1970; and a headscarfed Muslim head of state at a time when Muslim minorities in so many countries face undeserved suspicion. Symbolism matters in all kinds of human relations, whether it’s wearing a wedding ring or preserving a heritage building. It’s how we declare who we are and what’s important to us. The identity of our new president amounts to a big, bold statement.

Like many other Singaporeans, though, I despair at the way our eighth president entered the office. The government’s decision to turn the 2017 presidential election into a Malay-only race backfired badly. Shutting out potential candidates from the Chinese majority and engaging in crude tokenism tainted Halimah’s entry into the Istana. Worse, it unleashed a social media flurry of racist remarks in the guise of political comment, injuring the very harmony that the government claimed it was trying to promote. I can think of few political events that reveal so starkly the tendencies that prevent Singapore from maturing as a polity: the government’s distrust of the people, its insistence on getting its way, and its lack of finesse in dealing with contentious issues.

Halimah should have been allowed an open election

Photo by Lim Weixiang for Mothership.sg

Photo by Lim Weixiang for Mothership.sg

When the government revealed its intention to reserve presidential elections periodically for minority candidates, people naturally suspected that the constitutional amendment was designed to block Tan Cheng Bock from running again. Ironically, this cynical interpretation of the government’s intentions — which it has strenuously denied — actually makes it look smarter. If its goal was to thwart Tan at any cost, it achieved it 100 per cent. On the other hand, if we give it the benefit of the doubt and accept that racial harmony was its only policy objective, we are left dumbfounded by its chosen course of action. The idea of a reserved election was counterproductive, ultimately doing more harm than good. The government could have let Halimah stand in an open contest. It should never have mooted the controversial idea of radically amending the constitution, a move guaranteed to alienate many of the 64 per cent of Singaporeans who had voted against its preferred candidate in 2011. If Tan Cheng Bock wanted to run against Halimah, it should have let him.

I know many will disagree with this counterfactual prediction, but I do believe that if Halimah’s backers had focussed on talking her up instead of keeping Tan Cheng Bock out, she would have beaten him—and by a more convincing margin than Tony Tan managed in 2011. For a start, she would have the loyal, genuine backing of the labour movement, which she served from 1978. She would have had a good chance of winning over many of those Singaporeans who’d wanted a more relatable candidate than the patrician Tony Tan. Furthermore, many Singaporeans would have been thrilled by the chance to elect Singapore’s first female head of state. In the course of a campaign, younger voters would have discovered the Halimah who Her World chose as its Woman of the Year 2003. In a hypothetical contest between the two, Tan Cheng Bock would have had to tread carefully, lest he say anything that might come across as disrespectful to the female gender. The main thing going against Halimah, frankly, was that, unlike Tan, the government supported her.

But once they got to know her better through an open campaign, enough fair-minded voters would have realised that this feisty former backbencher had at least as strong a connection to ordinary Singaporeans as Tan Cheng Bock. Her parliamentary record shows that (relative to other PAP stalwarts, he was as well) she has as much of a claim as Tan to the mantle of an outspoken champion of the common man and woman. For example, she was the first ruling party politician who publicly chided party comrade Seng Han Thong over his 2011 remarks about the English language skills of Malay and Indian MRT drivers, which she called “inappropriate and unfair” and “simplistic and insensitive”.

Unfortunately, the government was convinced that Halimah’s strong selling points would be wiped out by her ethnicity. It decided that Chinese Singaporeans would vote for a fellow Chinese and not give a minority candidate like her a chance. Hence, the need to change the system and restrict this round to Malay candidates. Again and again, the government cited a survey by Channel NewsAsia and the Institute of Policy Studies, according to which around three or four out of every ten Chinese respondents wouldn’t say that they would accept a minority president. The survey implied that a Malay candidate for president would be rejected by as much as one-third of the population.

[related_story]

But were those surveys realistic?

But the government read too much into these survey findings. It is one thing to ask survey respondents to react to a hypothetical, nameless, faceless candidate of a given race. It’s another thing entirely to ask voters to consider a specific, real-life individual. In the former case, respondents can only respond through racial stereotypes — because they are not given any information to go on other than the person’s race. In the latter case, voters are able to consider the whole person. Of course, some voters may not see past the candidate’s colour. But many will respond to other salient traits, such as character and experience.

Thus, in the real world, there’s no contradiction between harbouring generalised prejudices against a particular race while at the same time developing a deep positive connection with known individuals of that very same race. The clearest evidence of this is the popularity of Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam. According to the IPS survey, only six in ten Chinese would accept a hypothetical Indian prime minister. Yet, a survey by Yahoo! the same year showed seven in ten supported (not merely accepted) Tharman as their next prime minister — twice as many as Teo Chee Hean, who came in second. Just as many Singaporeans who say they don’t want an Indian prime minister would love PM Tharman, it is entirely possible that Singaporeans who didn’t favour a Malay or Indian president would have happily voted for President Halimah. By reading the worst into the CNA-IPS survey, the government was underestimating both the national appeal of outstanding minority candidates, and the capacity of most Singaporeans to see past their racial prejudices when presented with a specific individual of undeniable worth.

Admittedly, there’s no guarantee that Halimah would have beaten Tan Cheng Bock. We might have had to content ourselves with a Malay president on our banknotes, but not in the Istana. The government wanted certainty. But this could only come at a very high cost. The point of elections isn’t simply to give power to winners. If power were the only thing at stake, contenders could do it the efficient Game of Thrones way and murder their opponents. No, elections are about conferring legitimacy. That legitimacy is a product of people’s democratic choice: their freedom to stand for election and their freedom to vote. But genuine choice makes elections unpredictable. To put it another way, you can have either legitimacy or certainty; you can’t have both. Trying to guarantee an election outcome—as the government did when it restricted the 2017 election to Malay candidates (and then to just one of them)—inevitably diminished the perceived legitimacy of the process. That was too high a price to pay.

The benefit of an appointed President

It would have been far more sensible to accept the suggestion of the 2016 Constitutional Commission, that the presidency revert to its historical role of a “symbolic unifying figure” appointed by parliament. Its veto functions, safeguarding the reserves, could have been taken over by a separate council. After all, it’s debatable whether Singaporeans were ever really convinced of the need for an elected, custodial presidency. Lee Kuan Yew had to push his idea hard against very many doubters. On the flip side, people used to accept without fuss the tradition of rotating the old-style office among the main races. The government could have just swallowed its pride, conceded that the elected presidency was a failed experiment, and boldly revived the ceremonial office that had served Singapore well for more than three decades. Instead, it opted for a model that is neither here nor there: an election stripped of free choice, to install a symbol of unity in a manner that sowed division.

Perhaps, though, the constitutional change would be worth it, if the costs were outweighed by the benefits. The stated goal was to give our Malay community the morale boost of seeing one of its own occupy the highest office in the land. As importantly, a Malay president—her photo in every school and government office, saluted at National Day Parades, receiving other heads of state at the Istana—would serve as a strong reminder to our majority race that Singapore’s minorities matter. Both are extremely worthy goals. But they can’t be achieved by installing a Malay president any old how. Symbols are powerful, but they require delicate handling.

First, basic knowledge of human psychology should tell us that if we want people to feel good, we need to respect their dignity. If your colleague needs money for an operation, there’s a big difference between discretely giving him the cash versus broadcasting your charity via your workplace’s group email. The former tells him you sincerely want to help; the latter says you’re showing off at his expense. Similarly, when performed the right way, token political gestures are appreciated by all ethnic communities. Think of how people lap it up when a guest of honour bothers to learn a few lines of their language to kick off his speech, or is willing to dress up in their traditional attire. But the same gestures would backfire if the VIP tried to milk them too much, or acted as if his hosts should feel grateful for his efforts. Everybody likes a gift, but nobody wants to appear needy. Tokens need to be presented with grace. Therefore, the government’s repeated, high-profile declarations that Malays needed a Malay president were bound to grate on the very community it was trying to impress. So it was no surprise that some Malays dismissed it as tokenism, and called for more concrete measures to uplift the community. The debate over Halimah’s Malayness was another symptom of the unease among Malays with the way things were handled. These objections would not have arisen if the government had not been so explicit about requiring a Malay president. If it had simply offered Halimah as an outstanding candidate who just happened to be Malay, she would have been embraced wholeheartedly by the Malay community.

Arming the racist subset

Second, the government’s move risks intensifying anti-Malay sentiment — the exact opposite of what it intended. The government lost sight of who the target audience is for its message of tolerance. Obviously, it’s not Malays themselves. Nor is it the majority of Chinese, Indians or others, who are already quite accepting of Malays. The main problem group comprises that subset of Chinese who harbour deep ethnic prejudices; those who believe that Singapore would be a better, more successful country if it weren’t for our minorities holding us back. These are the Chinese who don’t buy the theory that minorities face systemic disadvantages or that they need a leg up. In their worldview, Malays and Indians are not grateful enough for the space and opportunities they already enjoy in a Chinese country.

In the past, if you asked such people to identify the privileges they felt that minorities enjoyed, they might point out that minorities require a disproportionate share of welfare services. They would also claim that Muslims are more touchy than other religious communities: Singapore keeps having to bend over backwards to accommodate and not to offend them. But these grievances were never too extreme. Singapore doesn’t have anything that comes close to the affirmative action programmes of India, with its massive reservations system for university places and government jobs. Accordingly, majority resentment in Singapore is much less intense than in India.

The problem with the new presidential election system is that it goes to the very top of the list of reasons that any Chinese can cite to justify his anti-minority feelings. The constitutional amendment meant that the majority race couldn’t even contest for the highest office in their own country. Most Chinese will blame the government for this turn of events. But those with racist predispositions will see this as a new low in the way Singapore panders to its never-satisfied minorities. The next time the Malay community raises a legitimate grievance that it wants the government to address, such as discrimination in employment, these same Chinese will mutter that Malays are just too much: we handed them the presidency, but they still claim to be disadvantaged.

None of this is the fault of Halimah Yacob. Sadly, though, she is bound to bear part of the burden of the government’s mishandling of the presidency. Some Singaporeans, even within her own ethnic community, won’t get over the impression that she’s a token Malay. Some will see her as a reminder of how Tan Cheng Bock was robbed. I can only hope that most give her a chance, and that she’ll use it to help heal the divides that the whole controversy has exposed and widened.

Cherian George's new book, Singapore, Incomplete: Reflections on a First World nation's arrested political development, is now available for online pre-orders. You can find more information and purchase it online here.

Top photo: screenshot of Facebook live feed from Halimah Yacob's swearing in ceremony

Here are some totally unrelated but equally interesting stories:

There are tons of GrabRewards points you haven’t been using

These stories of the people from the Tampines Round Market will warm your heart

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.