Li Yao An runs Yew Chye Religious Goods Trading, a shop nestled within a housing estate in Jalan Minyak.

The 64-year-old man has been making and selling religious paper offerings, more commonly known as kimzua, at his shop for almost 30 years.

Having been in the business since the 1970s, Li is a master craftsman in a traditional trade.

In case you don't know what religious paper offerings are...

Kimzua offerings are paper replicas of everyday items (especially those of particular value) that are ritually burnt during religious ceremonies.

The burning is done in the belief that the items will reach those who have passed on into the afterlife, and will be of use to them.

The paper offerings are usually in particularly high demand during the Chinese Hungry Ghost Festival, when those who observe the festival will burn a lot of offerings.

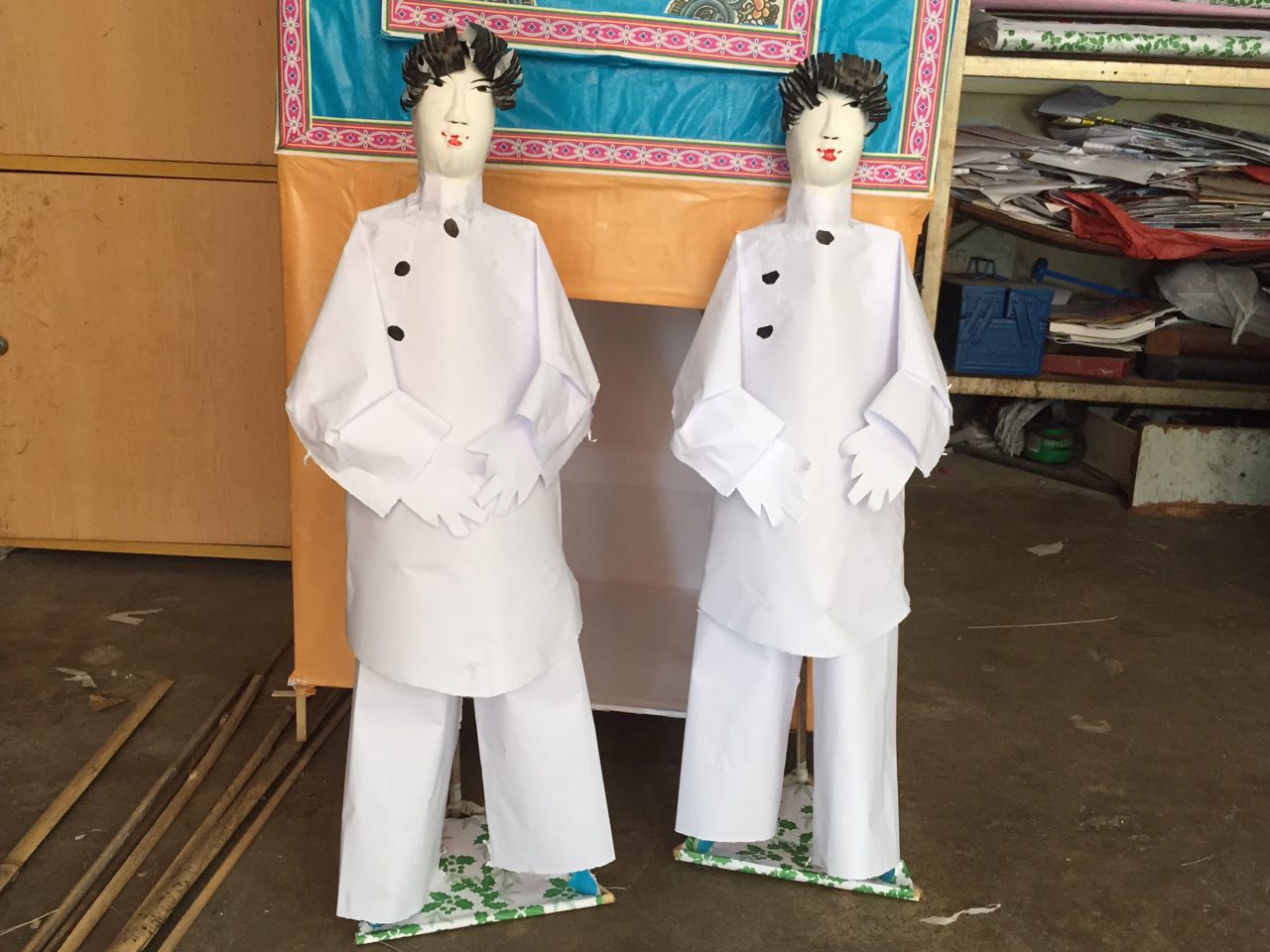

Traditional kimzua include houses and servants, while the more modern offerings include iPads, laptops, Rolex watches, and treadmills.

[related_story]

Different from the rest

Li prides himself on making his own paper offerings by hand, unlike others who'd import the kimzua instead.

But that's not all.

He told 1819 that his willingness to create modern, customised products was what made him different from other traditional stores:

"People used to want traditional things, but now they request modern products. It's like how the things we played with in the past is different from what you play with now."

All one has to do is show him a photograph of the object they want, and he will turn it into a paper model.

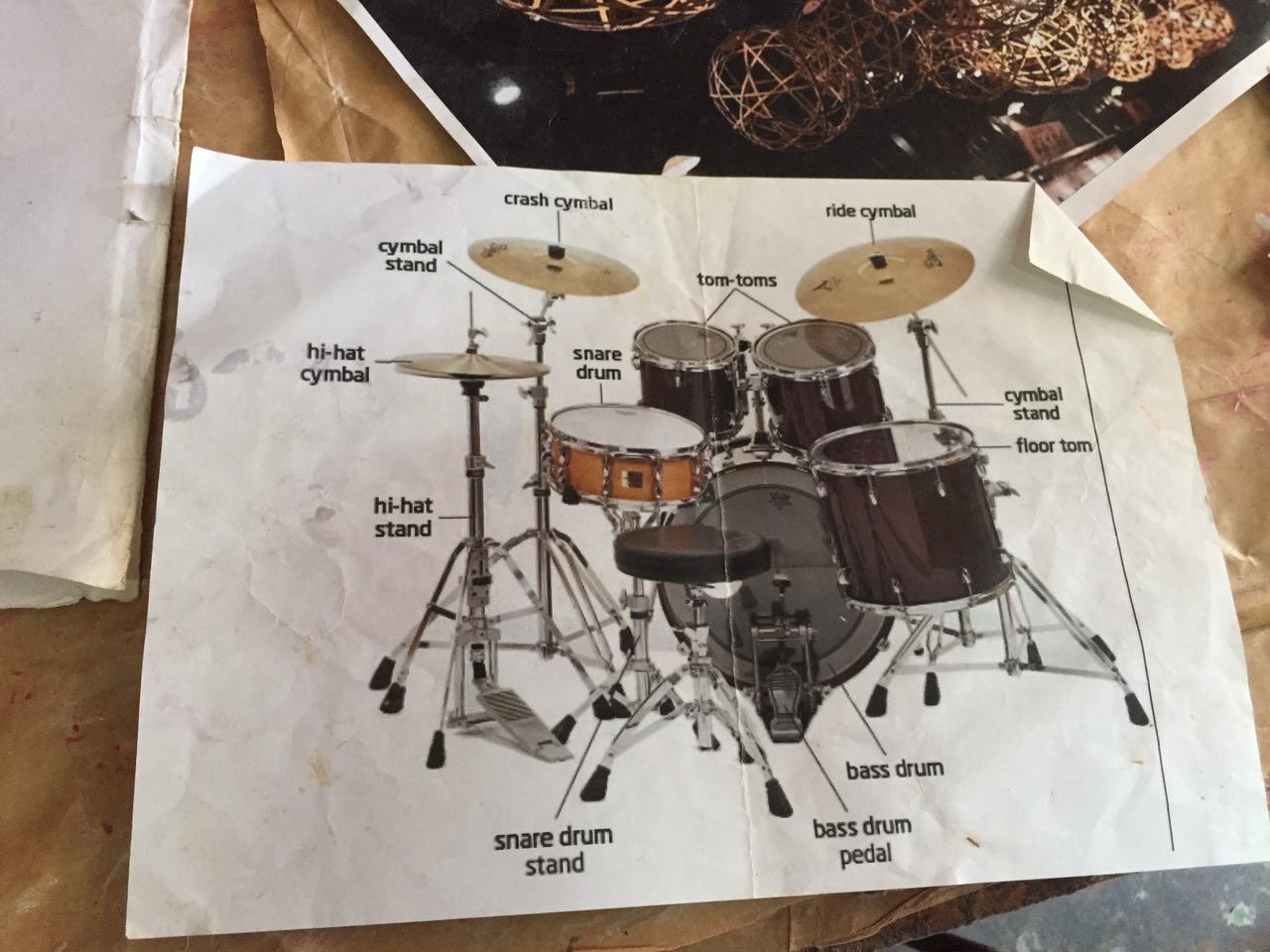

Some of the more interesting requests he has received include a dog, drum set, and camera that comes with different lenses.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

The importance of hard work and creativity

When asked about the most challenging order he has received so far, he joked that nothing daunts him, and then offered this piece of advice:

"The most important thing is to be hardworking and to have a nimble mind."

To Li, making kimzua is a form of art. The amount of creativity and critical thinking that goes into making paper-made models are not things that can be easily replicated or taught.

He cited the example of a customer who requested a huge dog, and explained that a lot of work goes into planning a customised order:

"When the customer told me that they wanted a dog, I had to think about it for two weeks. It took a lot of thinking to plan how to do it."

He proudly showed us a photograph of the finished model:

Photo courtesy of Li Yao An.

Photo courtesy of Li Yao An.

Li said that he has never rejected any customers to date. To him, every order is an opportunity for money to be earned.

On whether the high volume of orders received during the Hungry Ghost Festival is a source of stress, he merely laughed it off, saying:

"There is no need to feel stressed. We must live happily! If I can't finish the orders on time, I will just wake up earlier to start work."

Traditional methods and materials

Despite his innovative creation of kimzua products with a modern twist, the art of making paper offerings remains highly traditional. He still uses the same method and materials from when he first learnt the trade.

For instance, he has kept the type of paper consistent over the years. He also makes his own glue from scratch because handmade glue is cheaper and allows him to save money.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

One pot of glue lasts him about four to five days of kimzua making.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

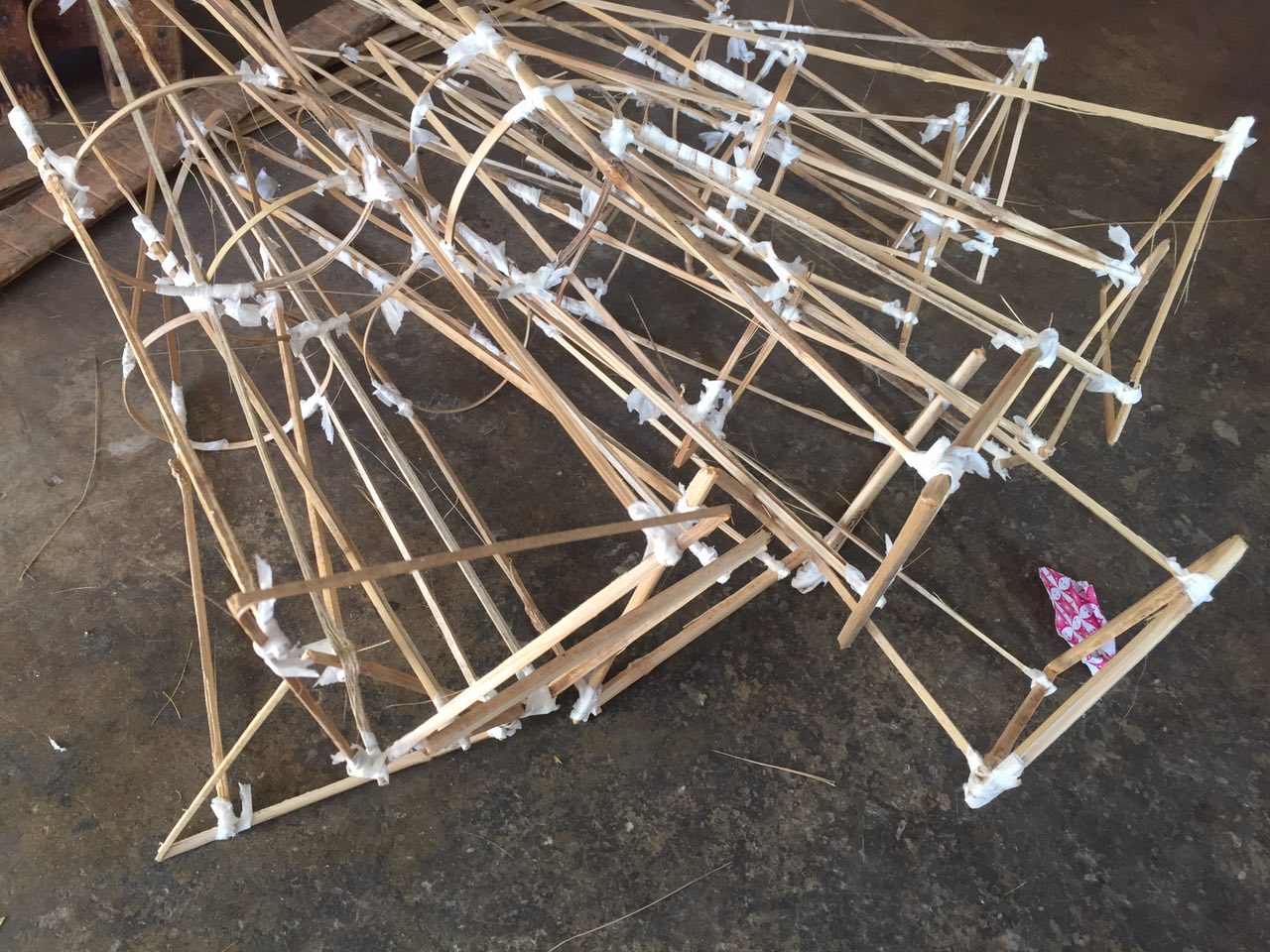

Li has also remained faithful to the traditional process.

He starts off by making a framework of the object. With great precision, bamboo strips are hand-cut for the frame. The bamboo strips are then bound together to form a structure.

Unfinished model of a boat. Photo by Tanya Ong.

Unfinished model of a boat. Photo by Tanya Ong.

[related_story]

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Next, strips of paper are cut out and stuck onto the bamboo frame using his handmade glue.

Li is so experienced in his craft that he does not need to measure the paper before cutting it.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

He also paints and details his paper offerings by hand, as seen with this painted head of a Ghost King.

Photo of the Ghost King's head by Tanya Ong.

Photo of the Ghost King's head by Tanya Ong.

Have a look at some of his finished products:

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

A dying trade

Li's first experience with making offerings for the dead began in Chinatown, when he was only teenager. He asked the boss of a kimzua shop if he could help out, and the boss agreed to take him on and teach him.

The learning process was not easy and proved to be back-breaking.

He was made to sit on a short stool for hours on end to prepare the framework of the paper offerings. The tiny brown stool is photographed next to the red pail:

Photo by Tanya Ong.

Photo by Tanya Ong.

He was slow in picking things up at the beginning, but he persevered in honing his skills.

After years of making kimzua, he finally accumulated enough experience to run his own business.

In the 1990s, with only $500 in his pocket, he started his present business at Jalan Minyak. It was an uphill endeavour with rent to pay, materials to buy and a family to feed.

But it was worth it in the end when he eventually managed to eke out a living from his craft.

However, to Li, making paper offerings is not just a livelihood. It is an art, but one that he believes will die with him.

None of his children have taken an interest in learning the craft or taking over the business.

He also found it unlikely that any youngster would be able to handle the physical discomfort of sitting on the stool for hours on end.

Successor or no successor, Li finds great joy in his work and hopes that he can do this until the day he dies.

Photo by Tanya Ong, polaroid pictures by Wee Jiahui.

Photo by Tanya Ong, polaroid pictures by Wee Jiahui.

Here are some totally unrelated but equally interesting stories:

Enhanced Internships — The next big thing? Two poly grads share their experience

Quiz: What kind of Singaporean will you be in a crisis?

Top photo composite image by Tanya Ong.

[related_story]

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.