Alfred Russel Wallace, the famed British naturalist, anthropologist, explorer, and biogeographer who co-discovered the theory of evolution with Charles Darwin, set out on an eight-year journey across the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862.

His goal was to collect various specimens to sell to museums and collectors in London, and to study the natural history of what was then called the 'East Indies' (Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia). Singapore was his first stop.

Wallace, Darwin and the theory of evolution

Though his name is often forgotten in favour of Darwin's, Wallace played a crucial role in the development of the theory of evolution and natural selection.

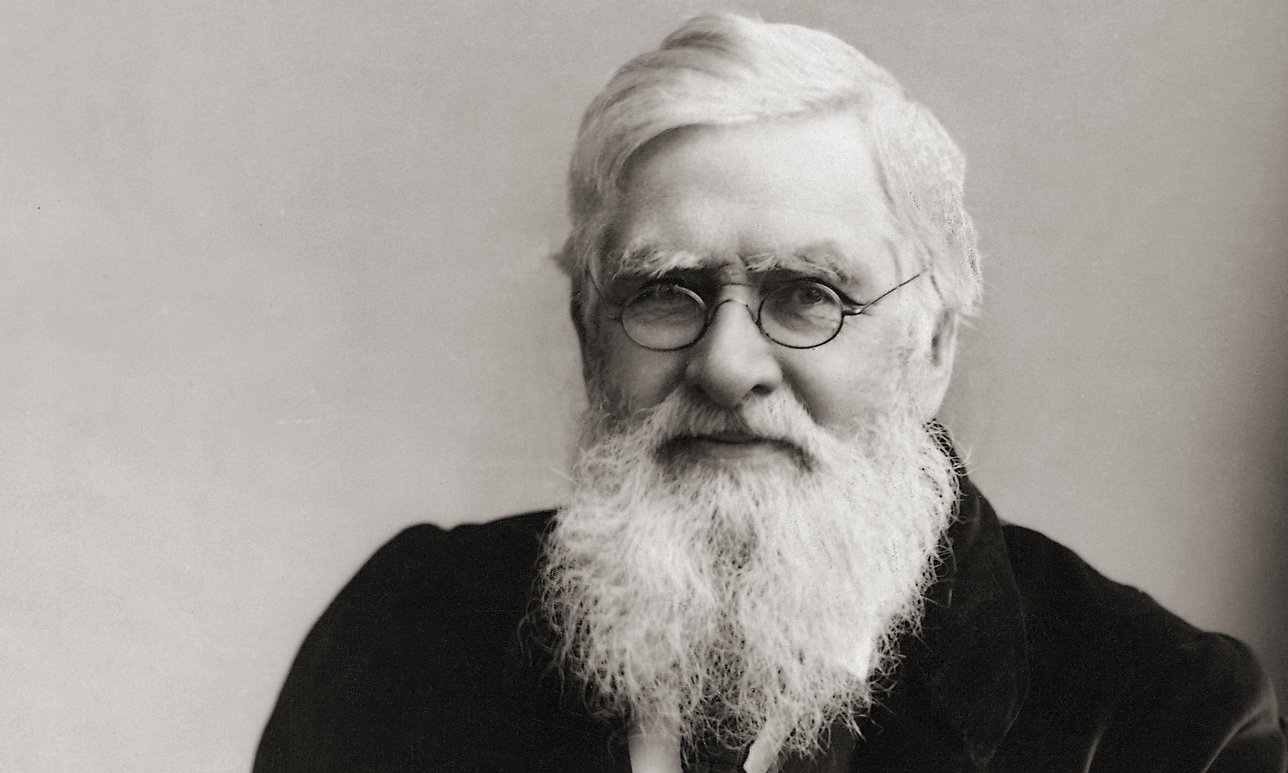

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="800"] Alfred Russel Wallace. Source: Wikipedia[/caption]

Alfred Russel Wallace. Source: Wikipedia[/caption]

During his travels, Wallace independently concluded that species evolve in order to adapt to their environments. He sent an early version of his work to naturalist Charles Darwin, who had developed the same theory years earlier.

Wallace's work, however, finally spurred Darwin into action. Together, both men published a joint paper on the subject. However, while Darwin went on to author On the Origin of Species, Wallace faded into relative obscurity.

Today, Wallace is still remembered in the scientific community for his meaningful contributions to early evolutionary theory. Some even call him the "father of biogeography".

Many of his groundbreaking discoveries would not have been made, however, without the thousands of species he observed and collected in Southeast Asia— including Singapore.

Wallace's wanderlust

This trip to the Malay Archipelago was not the first time Wallace had been inspired to travel abroad.

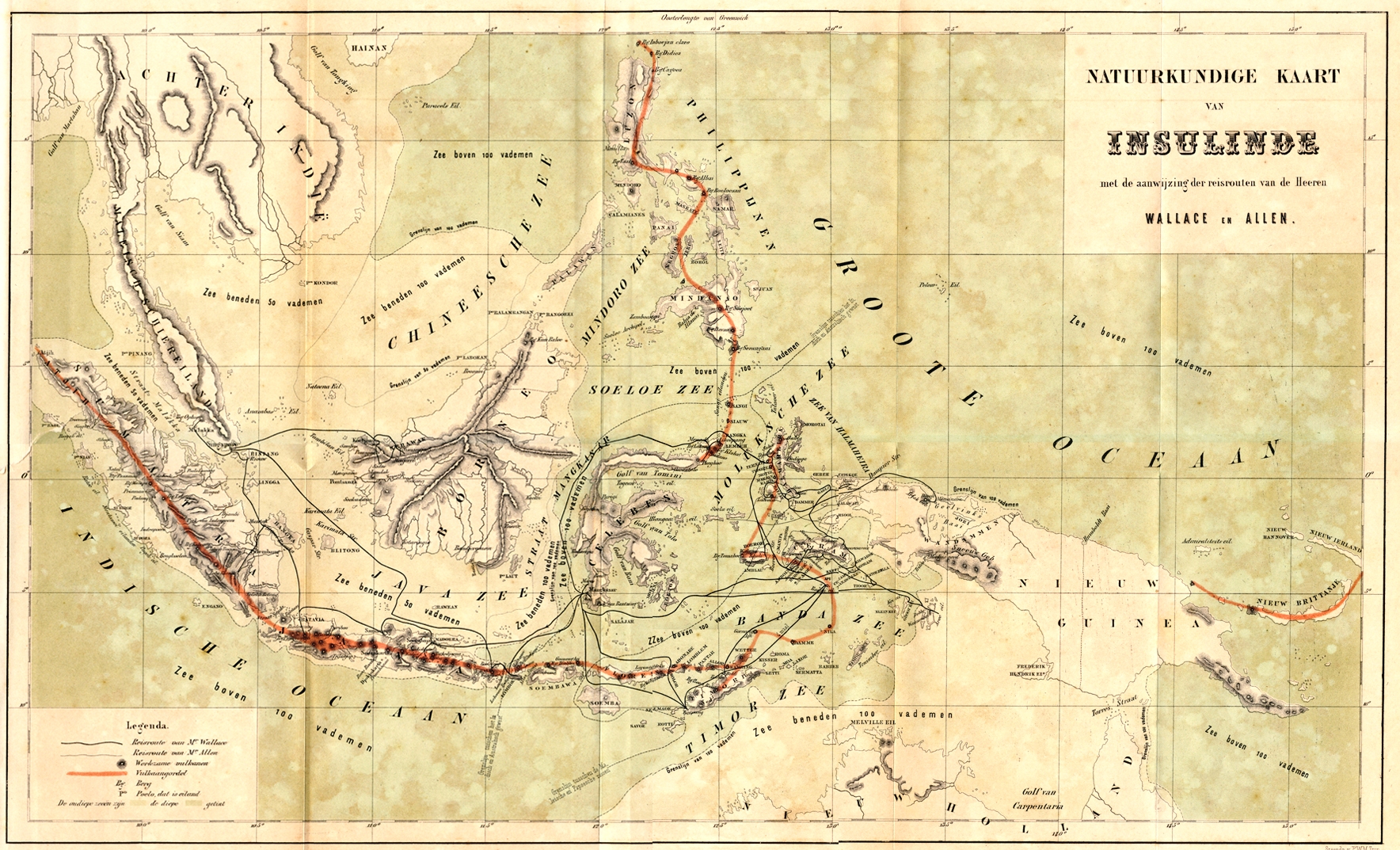

A map of the Malay Archipelago charting Wallace's travels. Photo via Wikipedia.

A map of the Malay Archipelago charting Wallace's travels. Photo via Wikipedia.

After reading the works of many travelling naturalists in his youth, Wallace departed England in 1848 on a four-year expedition of his own.

He and his colleague Henry Bates collected hundreds of specimen of flora and fauna from the Amazon rainforest, all with the intention of selling them back home. But, unfortunately, almost all of the collections were destroyed in a fire before the two scientists even reached London.

Wallace refused to let this setback stop him, nonetheless. After spending only 18 months back in England, he set off on another adventure.

This time he explored Southeast Asia, and he would return from this eight-year trip with things that revolutionised the way many people looked at the natural world.

Arriving in Singapore

On April 18, 1854, Wallace docked in Singapore aboard a Peninsular and Oriental Company (P&O) steamship.

Wallace would have probably docked somewhere along the Singapore River, with the backs and outhouses of buildings facing Commercial Square (now Raffles Place) greeting him.

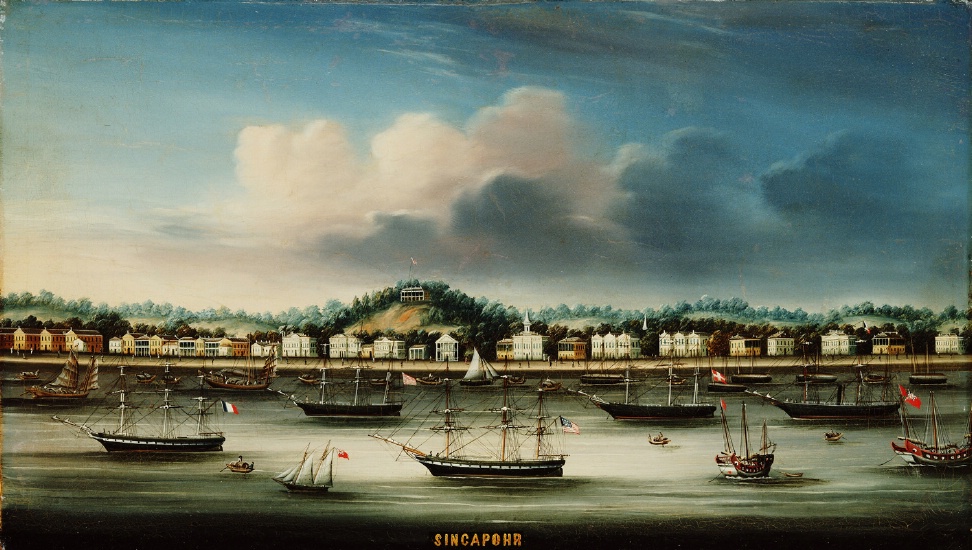

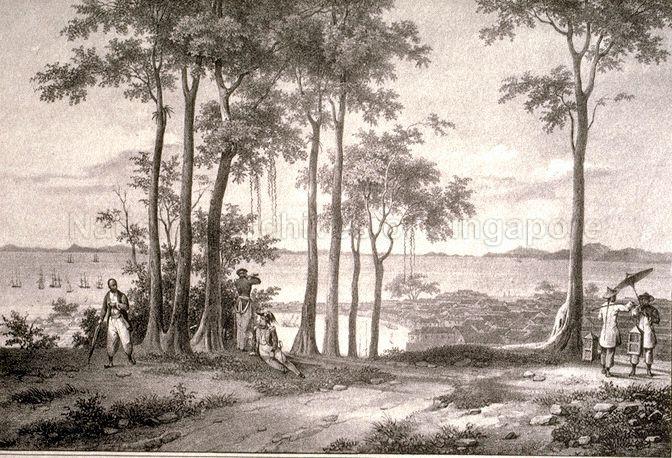

One of the few depictions of Singapore in the 1850s. Photo from Blue World Web Museum.

One of the few depictions of Singapore in the 1850s. Photo from Blue World Web Museum.

Colonial Singapore was, back then, a part of the Straits Settlements (Singapore, Penang, and Malacca) governed by William J. Butterworth, an unpopular Madras army general who was better known as "Butterpot the Great" for his pompous, uptight personality.

In 1854, Singapore was far from the safe haven it is today, and there violence between members of various secret societies across the island would have been common.

In fact, less than a month after Wallace's arrival, he witnessed the first outbreak of violence between a Hokkien shopkeeper and a Teochew customer at a chicken rice stall on May 5, 1854.

This incident would then escalate into the Hokkien-Teochew Riots (also known as the Great Riots of 1854), which would last for over 10 days, and result in the death of approximately 500 people and the destruction of 300 homes.

This would become one of the most severe conflicts in 19th century Singapore.

Not everything was entirely bleak, however.

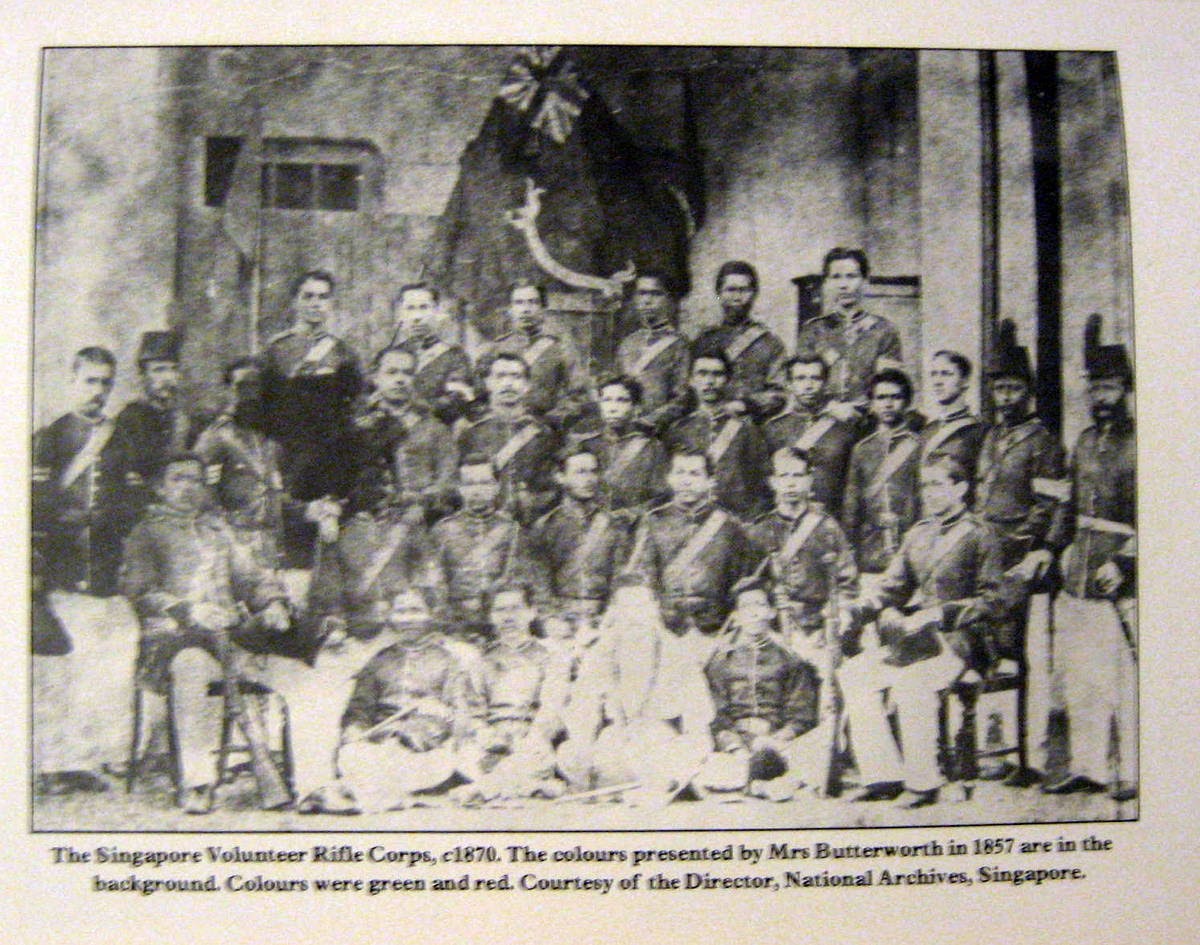

These riots would eventually lead to the formation of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps, who were comprised of civilians wishing to strengthen Singapore's internal security and sponsored by Governor Butterworth himself. Originally, the volunteers were exclusively European; later, different divisions would be created to promote ethnic inclusivity.

Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps, circa 1870. The original flag, sewn in 1857, can be seen in the background. Photo via.

Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps, circa 1870. The original flag, sewn in 1857, can be seen in the background. Photo via.

Capturing (bio)diversity

Being relatively unknown at the time, Wallace would not have received the same warm reception and invitations that Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein did in later years.

Wallace was not concerned with fancy dinners nor exploring the sights of Singapore. His written observations of Singapore would focus primarily on nature and living beings -— both human and otherwise.

During his first week on the island, Wallace made quick work of hunting for local birds and insects. Then, to get better samples, he moved closer to the centre of the island, bunking at St. Joseph's Church in Bukit Timah with a French Roman Catholic missionary.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="592"] St Joseph's Church (Bukit Timah). Source: History of the Catholic Church in Singapore website.[/caption]

St Joseph's Church (Bukit Timah). Source: History of the Catholic Church in Singapore website.[/caption]

Every day, Wallace would trek into the nearby forests and hilltops, collecting thousands of species and documenting them all. He even noted that he could hear roaring tigers hidden in the forest.

Portrait of Singapore and Residences & Residences from Government Hill (1850s). Photo from NAS.

Portrait of Singapore and Residences & Residences from Government Hill (1850s). Photo from NAS.

Interestingly enough, Wallace actually took notice of virgin forests being cleared in the area, and predicted that "countless tribes of interesting insects [would] become extinct" if the practice continued. He pleaded in his writings for Singapore's biodiversity to be surveyed quickly, lest it be lost forever.

If this is not done, future ages will certainly look back upon us as a people so immersed in the pursuit of wealth as to be blind to higher considerations. They will charge us with having culpably allowed the destruction of some of those records of Creation which we had it in our power to preserve; and while professing to regard every living thing as the direct handiwork and best evidence of a Creator, yet, with a strange inconsistency, seeing many of them perish irrecoverably from the face of the earth, uncared for and unknown.

Wallace's observations of early Singaporean biodiversity was done decades before any systematic cataloging, making his work some of the earliest snapshots of Singaporean wildlife.

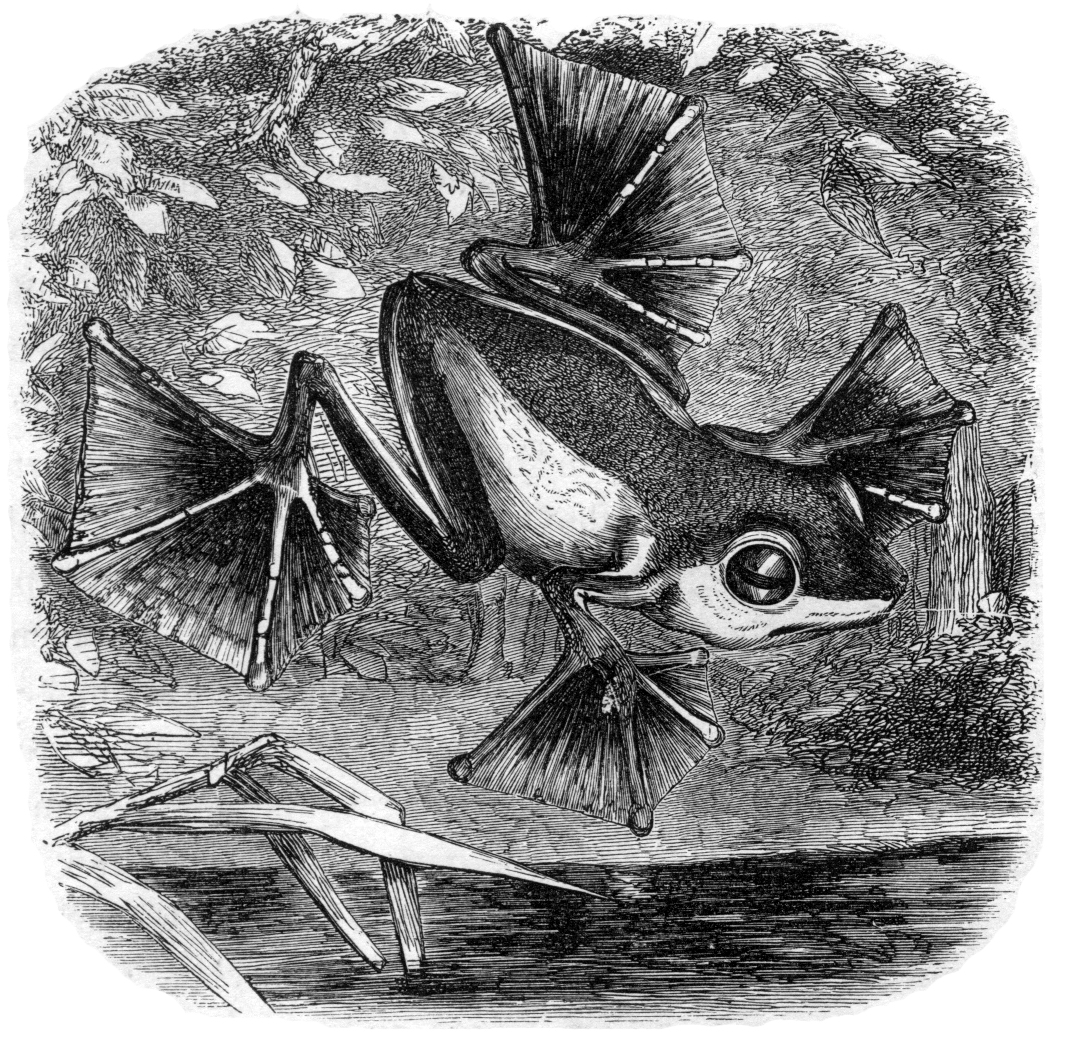

Illustration of a frog from The Malay Archipelago. Photo via Wikipedia.

Illustration of a frog from The Malay Archipelago. Photo via Wikipedia.

Some of his specimens remain in Singapore today, and can be found at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Wallace's collection at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. Source: The museum's website.[/caption]

Wallace's collection at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. Source: The museum's website.[/caption]

But aside from the diversity of plant and animal species, Wallace also reflected on the diversity of people he found in Singapore. In The Malay Archipelago (1869), a memoir of his time in Southeast Asia, he wrote:

Few places are more interesting to a traveller from Europe than the town and island of Singapore, furnishing, as it does, examples of a variety of Eastern races, and of many different religions and modes of life. The government, the garrison, and the chief merchants are English; but the great mass of the population is Chinese... The native Malays are usually fishermen and boatmen... The Portuguese of Malacca supply a large number of the clerks and smaller merchants. The Klings of Western India are a numerous body of Mahometans, and, with many Arabs, are petty merchants and shopkeepers. The grooms and washermen are all Bengalees, and there is a small but highly respectable class of Parsee merchants. Besides these, there are numbers of Javanese sailors and domestic servants, as well as traders from Celebes, Bali, and many other islands of the Archipelago.

Wallace was fascinated by the culture of early Singapore, and made many more observations about the people he came across, which can be found here.

In total, Wallace spent a total of 228 days in Singapore over several visits. He had a certain fondness for the island, which he summarised in a letter to his brother-in-law:

I quite enjoy being a few days at Singapore now. The scene is at once so familiar & strange... I am more convinced than ever that no one can appreciate a new country in a short visit. After 2 years in the country I only now begin to understand Singapore & to marvel at the life and bustle, the varied occupations, & strange population, which on a spot which so short a time ago was an uninhabited jungle. A volume may be written on Singapore without exhausting its singularities.

Here are totally unrelated but equally interesting articles:

Irrefutable proof why yellow is the new “in” colour right now in Singapore

We love to say “sweet until got diabetes”, but that’s not actually true.

Top photo from Wikipedia.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.