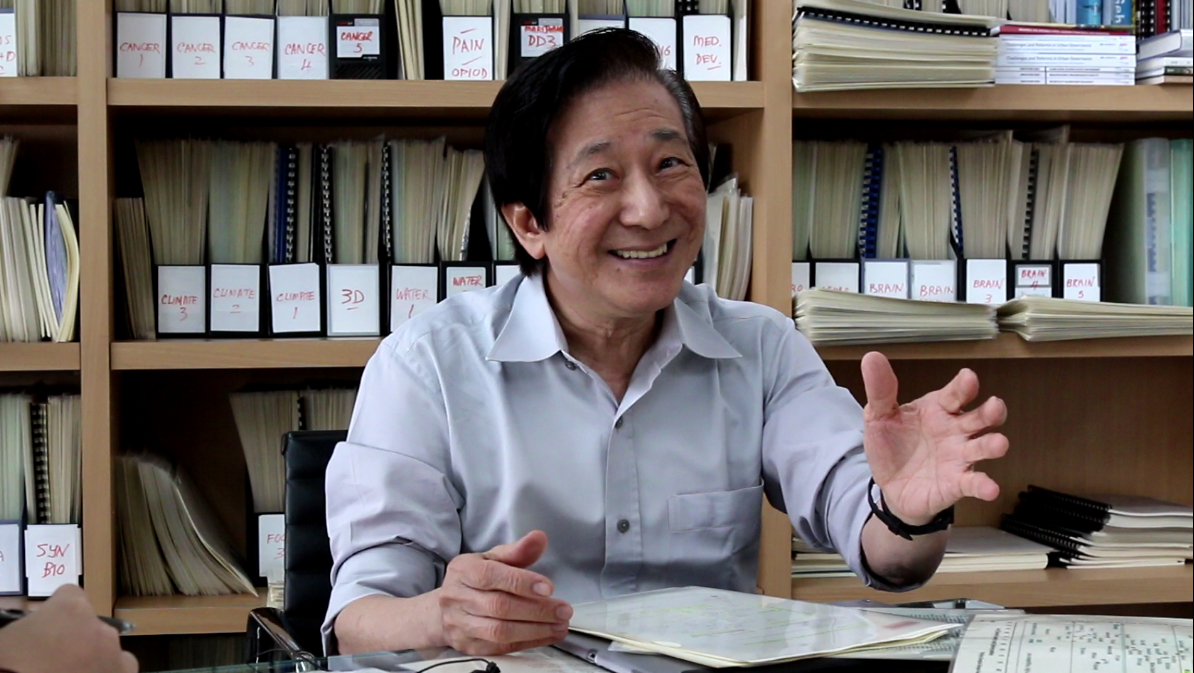

The outside of Philip Yeo's 21st-storey office at the Economic Development Innovations Singapore (EDIS) offers a picturesque view.

Looking out from a vast open-concept balcony space of the Symbiosis building, also home to SPRING, one inevitably spots, among the shiny buildings, clean-cut greenery and neatly-organised roads, the many container cranes of the Port of Singapore Authority, as well as the Keppel oil rigs... and of course, the place that came into being from land that didn't exist: Jurong Island. On the other side — Biopolis.

And the one thing these two places (well, three, if we count the area we were in at that moment) have in common: they wouldn't have existed if Yeo didn't dream them up.

In case this is the first time you're hearing this 70-year-old's name, you've lots to catch up on — he:

- got up and running the entire logistics division for the newly-formed Singapore Armed Forces, and armed them with weapons too — at the age of 24;

- made his name as chairman of the Economic Development Board (EDB) over one and a half decades (1986 - 2001);

- is responsible for the creation of Biopolis, Fusionopolis, Jurong Island and industrial parks in Bintan, Batam, Wuxi, Bangalore, Vietnam and Suzhou — as well as hundreds of thousands of jobs, both here and abroad;

- has five honorary degrees, including one in law.

Just to name a few. Suffice to say, Yeo has lived the dream every idealistic young graduate entering the civil service has: to make a difference, and to build our nation — or, well, at least have a hand in building it.

And heck, if there's only one person in Singapore who can say that about Singapore, it would be him.

His description of his achievements: "Collateral"

Yeo, by the way, counts himself as a non-salaried worker here. And he is — his chairmanship at SPRING is a pro-bono position, and he operates his three-year-old company from their offices at the same time.

But you wouldn't have had the faintest clue of that judging from his office, which doesn't fit into his actual allocated area and so unofficially takes up the entire area of two adjacent meeting rooms connected by movable doors.

Yep, that's a Mothership frame from us, right next to his Order of Sang Nila Utama (First Class). Photo by Jeanette Tan

Yep, that's a Mothership frame from us, right next to his Order of Sang Nila Utama (First Class). Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

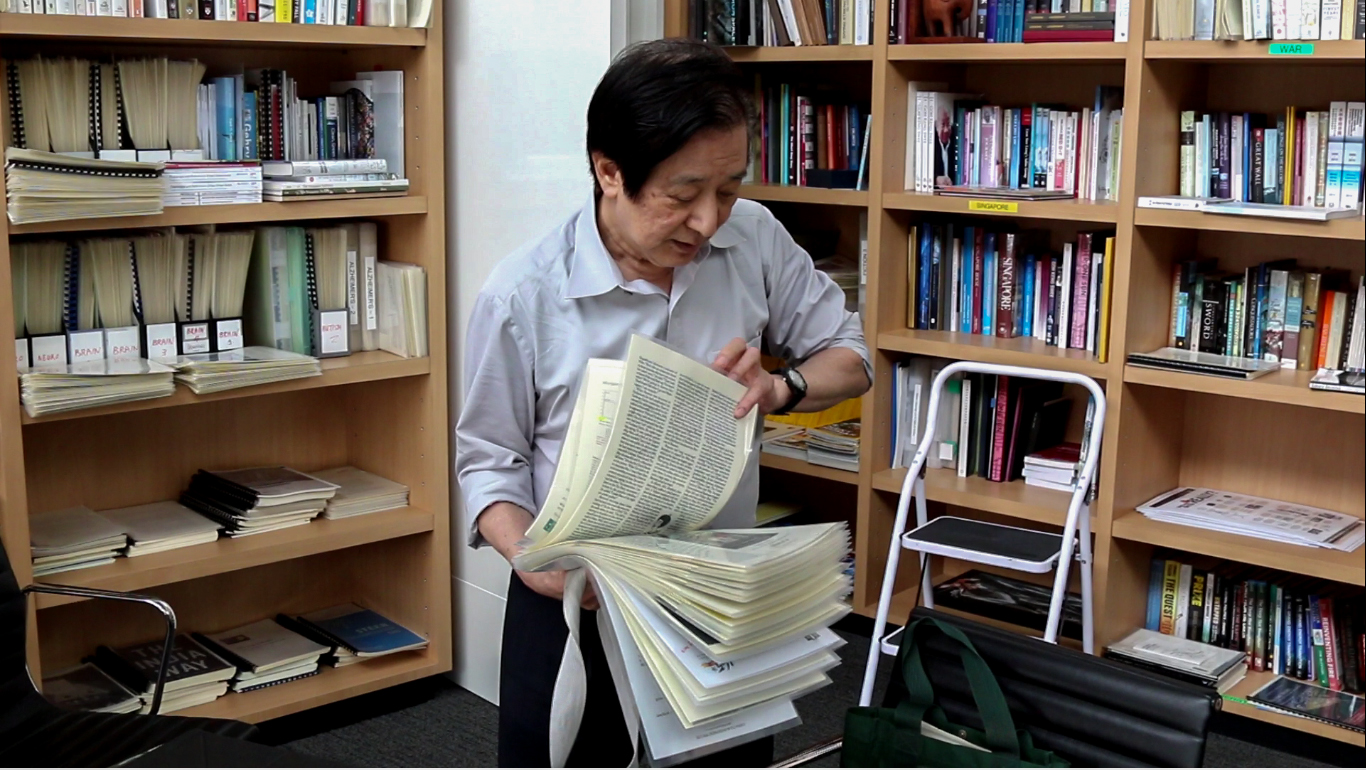

Inside this veritable brightly-lit cavern, apart from hundreds of books, magazines and thousands of his famous yellow-paper-printed articles, every flat surface (apart from the floor, although the perimeter of it is not spared) is filled with photographs, Yeo's collections, accolades, award certificates (he has so many, by the way, that he needs to run through a list to keep track of them), model planes and ships and even a wrapped and disarmed machine gun stowed somewhere in the corner of a nearby store room.

Yeo's workspace, and his famous yellow-paper-printed articles. Photo by Jeanette Tan

Yeo's workspace, and his famous yellow-paper-printed articles. Photo by Jeanette Tan

But enough about Yeo's office. Throughout our interview proper, which runs just over an hour, he leaps up at least three times to run off to the other side to rummage for an article to show us, brisk-walking and talking at the pace of a bullet train, even from the other room.

Plenty has been said about his demeanour and tendency to jump from one topic to another, and talk about anything from concentric castles to chimerism (don't worry, we didn't know what those were either), so one thing we wanted to ask Yeo was — did he ever stop for a moment to take it all in?

In response, he comments that he still gets stopped and asked for his pass sometimes when he enters the Symbiosis building in the morning, although it's usually because the security guard is new and isn't yet familiar with "this guy (who) is always running around".

And that's because he hates wearing it, and buries it somewhere deep in his wallet, where five other credit cards will fall out onto the floor when he pulls it out to dig for it.

"I mean to be fair, they are just doing their job," he says. And suddenly he answers my question by relating an encounter with a stranger who walked up to him outside a restaurant in Ho Chi Minh — the man came to Singapore, worked in Jurong Island, found a wife and settled down with Singapore citizenship, and wanted to thank him.

This, he admits with the slightest hint of wistfulness in his voice, made him truly realise that his work affected people's lives.

He goes on to share that two years after he kickstarted the Batam Industrial Park, more than 100,000 jobs were created. "They are all two-year contracts. So it's a constant turn. How many people's lives are affected, for better or for worse?"

70,000 IT jobs in the Bangalore IT Park in India later, and we haven't talked about Jurong Island (26,000 jobs), Biopolis and Fusionopolis (16,000 collectively), Bintan, Wuxi and Suzhou.

"So the things that I do, like it or not, affects people's lives. Right? So… to me it's just… what you call 'collateral'?"

Surely that's trivialising it, I thought.

"The thing is that I cannot be thinking so focused that I'm there to create jobs for everyone. No. I'm trying to help those countries create jobs for people but whoever works there I don't know."

Books, books and more books, in this case organised by country. Photo by Jeanette Tan

Books, books and more books, in this case organised by country. Photo by Jeanette Tan

Philip Yeo, "retiree"

But perhaps this gives some insight into how he operates — for a man who has done so much in his life, it would've been impossible to get as much done as he did without to some extent being touch-and-go about some things.

And that shouldn't be written in past tense either: as a self-declared "retiree", Yeo continues to sit on many, many company boards, travels extensively to places as far as Kazakhstan, Colombia, and Riyadh on a regular basis for meetings (as part of his work in EDIS), and just before receiving us, he was in a conference call with two German executives (one in Frankfurt, one in Hamburg), and the company's secretary in Astana, Kazakhstan, whose board he sits on too.

"What I do is corporate life in Singapore, government work, my own work and advisory work. So that's it. That keeps me busy lah... the most dangerous thing is boredom."

He reads voraciously, too — many have touted his ability to hold his own in discussions with established PhD-holding researchers in almost any biomedical discipline, and on one of his on-his-feet moments, he paced up and down a row of at least 10 international magazine subscriptions he personally has, and reads, at the moment.

Random trivia: Yeo was in 1991 voted as one of Singapore's 25 sexiest men by Her World magazine. True story. (Photo of page in "Neither Civil Nor Servant")

Random trivia: Yeo was in 1991 voted as one of Singapore's 25 sexiest men by Her World magazine. True story. (Photo of page in "Neither Civil Nor Servant")

Yeo also has a "green bag" — two recyclable cloth bags filled with clear folders of articles he gets his longtime secretary, Mary, to download and print out, complete with red pens, for notes, and yellow highlighters.

If all this makes you think Yeo is a scatterbrain, know that he is clear about where every single thing he has is. Every article he has printed out, for instance, is organised by country, topic, sub-topic, publication, arranged in order of date, and placed neatly into clear folders, followed by clearly-labelled box files.

And as cluttered and jam-packed as his workspace appears, it's actually remarkably neat and organised — another possible indicator of how Yeo juggles so many roles, responsibilities and tasks at the same time, and still have so much energy throughout.

But we digress — there's plenty more about Yeo we want to tell you about.

Steamrolling the civil service like a badass

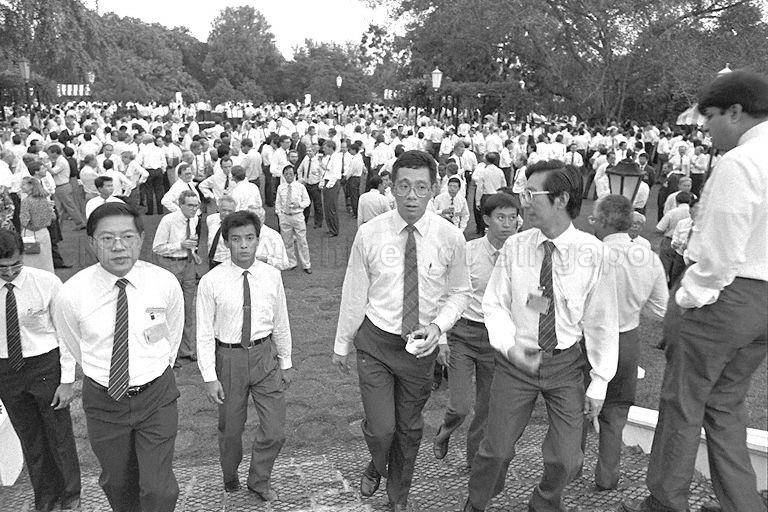

(Cocktail) Partying with now-PM Lee Hsien Loong at the Istana. Photo via the National Archives Online.

(Cocktail) Partying with now-PM Lee Hsien Loong at the Istana. Photo via the National Archives Online.

For instance, his time in the civil service has been likened to a steamroller — in the words of one of his protégés George Yeo, "if you stand in the way, you get run over".

Yeo was never one who bothered about bureaucracy and approvals — a recent book about his life by former newspaper editor Peh Shing Huei (which is flying off the shelves, by the way — 15,000 copies in four print runs so far) tells many stories about his exploits, which fortunately enjoyed the backing of leaders like the late Goh Keng Swee.

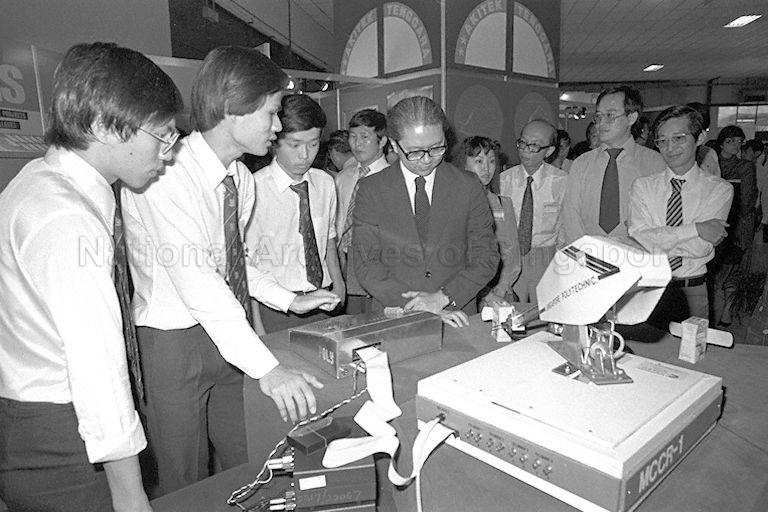

Here's Yeo with now-President Tony Tan back in 1983, still in his mid-30s and in MINDEF. He was probably folding his arms with a smug smile because by this time, he sneakily got approval for an "intermediate business machine" (a computer) for use in MINDEF even though at the time only MOF was allowed to have one. Photo from National Archives of Singapore

Here's Yeo with now-President Tony Tan back in 1983, still in his mid-30s and in MINDEF. He was probably folding his arms with a smug smile because by this time, he sneakily got approval for an "intermediate business machine" (a computer) for use in MINDEF even though at the time only MOF was allowed to have one. Photo from National Archives of Singapore

The way he operated is unheard of today — Yeo wasted no time with report or proposal-writing, simply walking in and out of Goh's office for three-minute conversations, and quite early on, even got the green light to sign cheques of up to a million dollars for whatever project he needed to do.

"So (Goh's) generation, entrusted us to do all the work. So that's it. How do I brief him? Lunchtime or meeting I just tell him verbally what's happening and update him verbally. I don't even write a note to him. Right? Because he trust me and he knows my work, it's easier to operate, see. So that's a world of difference."

He advocates stealing, for instance, like how he "stole" hundreds of qualified systems engineers who worked in other army divisions as storemen and clerks to form his logistics division in MINDEF, while on their dime (so they worked for him for free), stripping down rifles and figuring out how to make our own machine guns.

(It's at this point, of course, that he stresses, "For the public good! For the public good! Never for personal gain. Ha! That's the difference, you know. When you're doing it for the public good, you're trying to get something done. It may offend some people, you may overstep your authority or boundary… yeah.")

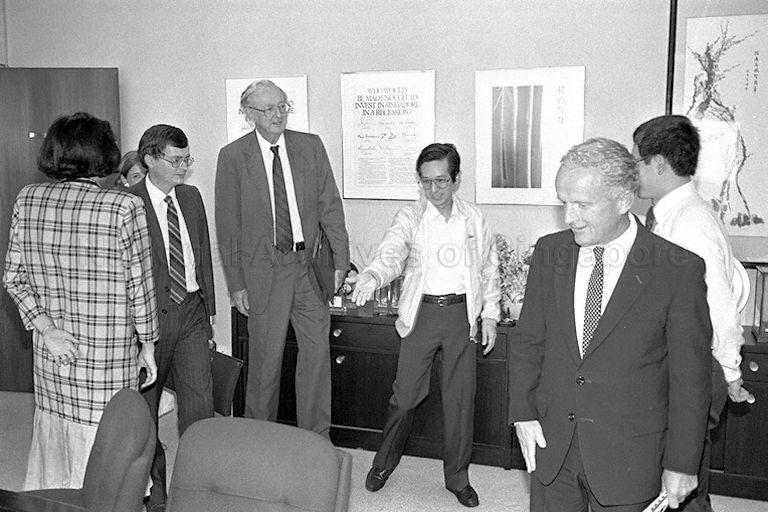

Who else will receive a foreign dignitary in a windbreaker? Classic. Photo from National Archives Online

Who else will receive a foreign dignitary in a windbreaker? Classic. Photo from National Archives Online

At the helm of the EDB, Yeo fired officers he didn't like, and any meetings he chaired wouldn't run longer than 15 minutes:

"If I chair meetings and if they are late by 15 minutes, (the) meeting is gone already. Cause if you come to the meeting, you must have read the papers. What I want (in) the meeting is to decide yes or no, or KIV or whatever.

What I don't want the meeting is: oh, by the way, let’s read page one line one line. Like, you send me these questions, I read already I tell you what I want to do, finish."

And when he was busy being Singapore's salesman, convincing big-time American companies to set up operations here, Yeo went to some pretty unorthodox lengths to make things happen.

These included calling up the principal of the Singapore American School to request a place for one company CEO's son, because his wife refused to move to Singapore without one, for instance, and negotiating the release of two pet dogs belonging to the Singapore-based boss at Levi Strauss, which were kept in the pound for regulatory reasons, because his children were upset that they were separated. Yeo also arranged for specialist medical treatment for family members of Indonesia's political elite, and is still close friends with former Indonesian president B.J. Habibie.

We couldn't help, knowing all this, but ask him — did he never consider the impact of his actions? How people would view him?

"The way I work is I got a job to do and I get a job done. And that's the way I still do, as far as I'm concerned. If you stand in my way, good luck to you. Right? Because as far as I'm concerned, I got a job to do.

Now. What's the impact? People don't like me. They get angry. They block me. That's life. But will everybody do that? Most people don't want to do that what. Right? Huh? They want to be loved, they want to be liked.

For me, a job is the most important thing. To get the job done because my job is really, I have an idea of what to do, I get it done. Right? Because I have no personal gain. I’m doing it for public good. So I don't understand why people should be obstructing."

Can a civil servant today still be like Philip Yeo?

Photo by Chiew Teng

Photo by Chiew Teng

Yes, he responds emphatically. But a person who wants to work the way he does — and did — needs about 20 bucketsful of courage.

"Why can't people do that? Because it's not safe. When you do (things) the way I do, means I carry a lot of risk, whatever I want to do right or wrong, whose head is on the chopping block?

Because if I am responsible, I will do it myself. If I give the work to you, and you don't want to carry the responsibility then why should I give it to you? Why should I give you the work when you don't want to be responsible?

...

If you are scared that you will offend people then you get sacked then obviously you won't do it. For me if I get sacked, I'll be happy to go outside. It doesn't bother me. That’s why I say, if you are a career-minded person, you will not do these things. You are doing a job because you want to achieve something. Right? Therefore you will just do it. If I offend you and you don't like me that's your problem. That's reality what.

So if you are career-minded, you will think twice about offending people and get a black mark, get a negative performance, not cooperative ah. So it's not the time, it's the personality of the person... (if you) choose to say that cannot be done because of (the) present climate, that's bullsh*t."

If you're thinking about career, you're doing it wrong

Rubbing shoulders with the right people. Photo from the National Archives Online.

Rubbing shoulders with the right people. Photo from the National Archives Online.

And that's where he talks about career — a mere mention of the word sets him off, declaring he would never hire a young person who in an interview with him, asks about what their "career progression" or "career path" would look like taking on a job.

He firmly believes one shouldn't be thinking about building a career — after all, he never thought about that in all his decades of work, and in fact says a person should quit a job he or she doesn't enjoy:

"The good thing is I'm always doing multiple jobs. So I don't have a career in that sense. Whatever appointment I have is just means to an end. The end is: get some project done; get something done. Whether I build a weapon, build a tank or a ship. Or get investors and so on...

Because when you have... if you define a career, that means you are worried about what is the next step. The key is that you do a job, you stay at the job as long as you like it. Enjoy doing it. If not, move!"

He also doesn't describe all his working life as a "career" — the words he prefers are "like a rabbit hopping around".

"The key is this: there must be something — when I'm doing this project, finish, I look for something else. Something else to do to keep the activity going."

And that's why Yeo famously declares he will work until he cannot walk.

Travelled to China umpteen times, but hasn't seen the Great Wall

Photo by Chiew Teng

Photo by Chiew Teng

But that plan will also get in the way of something else he wishes he could do but doesn't seem to be getting round to: travel... for fun.

For all the travelling he's done over the years to so many countries all over the world, Yeo admits he knows little beyond boardrooms, office walls and corridors, and perhaps the occasional restaurant or joint he is brought to by his host company executives.

He goes to Kazakhstan and Riyadh four times a year, and has been travelling to Saudi Arabia since 2012, but has yet to see anything outside their cities, or indeed anything vaguely touristy. Yeo even says he was offered, but had to turn down, a free helicopter ride over the Great Wall of China — a fantastic idea, to his mind, so that he won't have to waste time trying to walk its length — but it happened to clash with a meeting he had in Shanghai.

"So I have one collection of papers on travel. I collect articles on travel but I have no time to travel, there’s one whole box, no time to travel. They are very good articles and then I read them; so I read them and I say, maybe someday I will travel. Never happen."

The way Yeo sees it, travelling free and easy is not productive, and therefore not focused, and thus, it follows, not worth doing.

How old does he have to be to find this activity worthwhile, then, I ask — he says "until my legs cannot walk".

I then point out that travelling becomes significantly tougher without being able to walk, and he responds, "Ya, that's the challenge. Then you sit down and read lah."

They're not related, in case you were wondering. Photo from the National Archives Online

They're not related, in case you were wondering. Photo from the National Archives Online

(By the way, Philip Yeo is also chairman of Mothership.sg's board. Cool right? We also say.)

Here's an article you should check out:

This auntie, who looks like uncle, explaining investment scams is more effective than any PSA

Top photo by Chiew Teng

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.