“Almost Famous” is a new feature interview series on Mothership.sg. Here, we bring you in-depth stories of people who could be more famous, with a new interview released every fortnight.

We found Kumaran Sesshe at the Singapore Zoo on a Thursday morning waiting for us at a series of wooden tables and chairs at a dining area.

Despite how normal this scene sounds, he looked slightly out of place — possibly because as the head keeper for Great Apes, he would usually be standing away from where we were seated, near a collection of rocks laid together neatly in front.

That's where the zoo's morning breakfast programme takes place at 9:30 on the dot.

A delicious spread of fruit is laid out, and a few orange-haired orangutans — two larger, two smaller — would climb down to partake in the feast, while a presenter shares informative tidbits about them with visitors seated nearby.

We would soon discover that despite the short, stout man's age — 42 — he speaks as animatedly and passionately about animals as a teenage geek would about his favourite comic heroes.

His first love was snakes

And it took just one question — how he got into this line of work — for him to volunteer one of many fascinating stories he has to tell: how his love for animals first began with snakes.

The place he first encountered snakes was, of all places, during his National Service stint with the Singapore Police.

"I was exposed to a guy who was teaching us how to catch snakes in the police force, and I started loving snakes a lot during my NS days," he said.

Back then, the police handled everything — including wild animals on the loose.

"Whenever there's a case of a nuisance snake call... I used to go down and catch pythons and black spitting cobras even though it was out of my sector. If it's within my division, I will still go if they call me down. Even if it's an off-day and I'm off-duty and everything, it just started there."

Kumaran soon became so good at rounding up wild snakes and depositing them at the zoo that he started to conduct courses for his fellow police officers on catching and overcoming their fear of the reptiles — everything from garden snakes to full-grown pythons.

In order to do this, though, he admits he skirted the law in keeping several of them as pets, including two (large) wild pythons, which he sealed in a gunny sack.

It takes some prodding, but he eventually reveals he had as many as 18 snakes in his personal collection. He also tells us about the time one of his pythons slithered out of his sack, just as his mother was entering his room to put something on his bed.

"She freaked out of course, called me and said 'I don't care where you are patrolling, you come home now and get the bloody snake!' Lucky where I live is within my patrol area, so I could go home fast and get the snake back into the bag and secure it properly."

Kumaran says he did head-counts of his snakes to keep track of them every day, but even when one was missing — a large python, for instance — he was so comfortable with all of them that he often decided to go to sleep first, and then wake up in the morning to hunt for it.

"I think it's somewhere in the room, lah — (so I) just sleep first, too tired to worry about it you know. But he'll (the snake) be in the room because the gap between my door (and the floor) was really small; I know they cannot get out of my door, and then my windows are always closed. So I know they are somewhere in my room... you know, bachelor rooms, those days, you have a lot of stuff around. So I just don't bother looking for it."

Now, before you go off running to the police or the AVA about this, fret not — Kumaran's superiors knew about his reptilian pets, and even handed him several awards for his contributions to the force.

He can also tell us about his secret illegal stash of snakes now because he donated all of them to the zoo upon joining it — he told his boss, then-senior keeper Alagappasamy Chellaiyah, better known as Sam, that his collection included exotic species, which Sam was in turn happy to accept for the zoo's various programmes.

Perhaps his childhood experiences helped lead him to the zoo, too — Kumaran said he and his friends spent the majority of their weekends in forested areas near Woodlands, where he has lived all his life.

"So Saturday morning, first thing in the morning, we get up, all of us gather and go into the forest — (we) just do trekking and cycling, and we come back out only at 4pm, just in time to go get a snack or something, and come back for soccer. From 5 to 10 we would be playing football in the court, then go back, eat dinner, sleep, wake up the next morning Sunday and start the same routine, back into the forest! That's the only thing we (did back then). Weekends was that."

All that time spent outside exposed Kumaran to monkeys, snakes, monitor lizards, squirrels, fish and other wildlife, and he said that was why neither he nor any of his friends ever feared animals.

All this notwithstanding, it was certainly his experience with snakes during his NS that made him decide near its tail end, pun intended, that he wanted to spend his career working with animals full-time.

So eager was he that he applied to join the Mandai zoo, while still having three weeks to go on his NS stint. He even omitted mention of a National Technical Certificate Level 2 that he obtained in heavy-duty diesel engine mechanics as he did not want to be sent to the zoo's maintenance department.

To his astonishment, his interviewers asked when he could start, and when he said "anytime", he was told "Okay, you start tomorrow".

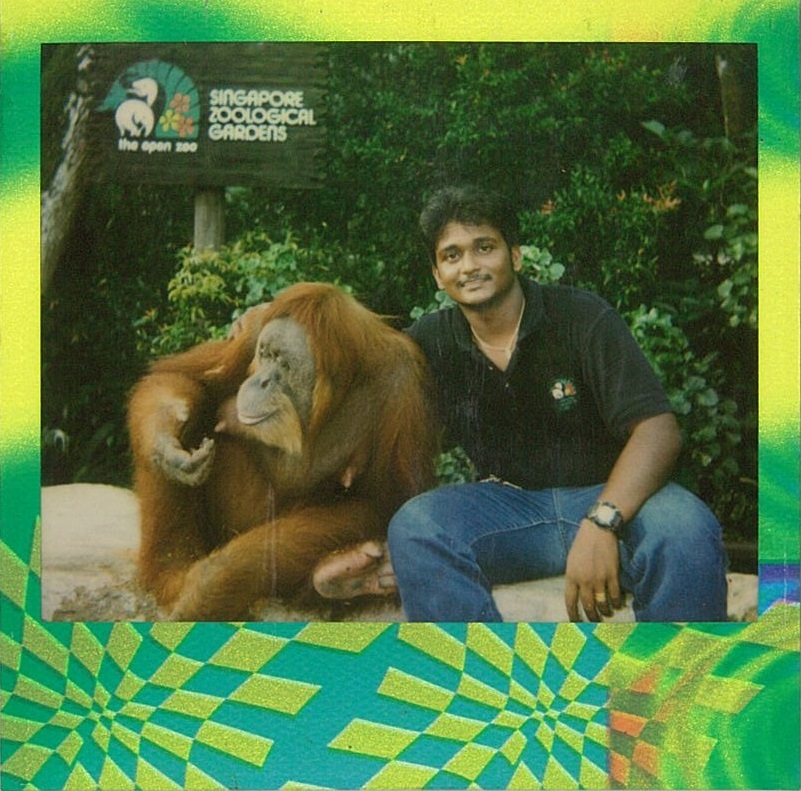

Kumaran with the old Ah Meng. (Photo courtesy of Wildlife Reserves Singapore)

Kumaran with the old Ah Meng. (Photo courtesy of Wildlife Reserves Singapore)

As much as he yearned to work in the reptile department, however, Sam, who is famously known as the late Ah Meng's longtime keeper, advised him to work with orangutans instead, noting that the increased hands-on contact provides for a better career path and faster progression.

Today, Kumaran says he is glad he listened; his affection for the apes blossomed in the 20 years he has spent working for the zoo — from having to spend the night camping below a tree because one orangutan refused to climb back down and return to the den, where they are kept overnight, to earning the right to cut the umbilical cord of a new orangutan when it is born.

So familiar he is with the orange-haired apes, as well as the most famous of these, the late Ah Meng, that he also played a key role in the eight-year selection of the young Sumatran orangutan who would become the "new" icon for the zoo and every Singaporean who loved her, in the years after she died.

He shares his take on his considerations for the new Ah Meng in this video:

[video width="1280" height="720" mp4="https://static.mothership.sg/1/2016/08/Sequence-02_CLIPCHAMP_keep-1_CLIPCHAMP_720p.mp4"][/video]

Distinguishing one orangutan's poop from another

So what is a day in the life of an orangutan keeper like?

Kumaran says he and his team of 11 keepers (seven, including him, with orangutans, and five with chimpanzees) keep regular office-hour-style shifts over rostered five-day work weeks, starting his morning at about 7:30am (he goes in early), and finishing by about 5pm.

"I like to check on the animals first thing in the morning. I will go to the two den blocks, do a physical check, call them — if they are lying down, I make them wake up... because I want to make sure that they are okay. Sometimes, they are lethargic or not feeling well, and then (if I can handle them) I will go in... touch their foreheads, see whether they're running a fever. You know, they are like us. They catch the common cold, fever, cough."

The man may be the guy in charge, but we would later observe that he does all the heavy lifting right alongside his fellow keepers. They move with the orangutans together, they take turns looking after them in equally-spaced shifts and exchange observations as equals, with no sign of seniority or hierarchy among them whatsoever.

Kumaran says he and his keepers have worked with them for so long that they can immediately tell who's who, know all their quirks — and point out to visitors the naughty, the cheeky, the playful — and can even tell if they're about to poop, and warn visitors to steer clear from, ahem, falling fecal matter.

"You don't just stand and poop, right? You need to pull out your butt, squat or something. Or the facial cramp. You work here long enough, you will know whose poop is whose. You can even differentiate the poop."

He adds that the babies often cheer him up at the end of a stressful day, climbing onto him, playing with him or holding their hands, seeking a cuddle.

How they throw tantrums, fight with one another to be first in line for fruit, or try (and fail) to queue up again in a bid to trick their keepers into a second piece, is also a frequent source of amusement for him and his colleagues.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Now that the zoo has opened an expanded "new phase" area for its orangutans, part of Kumaran's morning is spent there with them, allowing a few of them to explore it at any one time to begin with.

His team conducts keeper interaction talks with visitors at 11:30am, 2:30pm and 4pm as well, where they share "things that people can't find on Google" — such as how they are trained to put their foreheads to the den grilles to allow keepers to check for fever, or to offer their fingers for blood tests, for instance.

Meeting his wife

The zoo also happens to be the place where Kumaran found human love.

He relishes the memory of exchanging shy smiles, his and byes with a girl who started out volunteering with the zoo for a decade before joining full-time.

"I started asking her out for coffee, and then she told me, 'You've got 11 minutes to reach Ang Mo Kio if you want to go for coffee.' I was at Woodlands, I just got into my carpark, she said 'You've got 11 minutes before my bus comes', so I think that day I ended up breaking the speed record, speeding all the way to Ang Mo Kio. And we have a lovely 2-plus-year-old son now."

Today, Kumaran's wife works as an animal management officer at the River Safari's Giant Panda Forest — making them both managers at the two parks' respective flagship exhibits.

He admits he isn't particularly fond of the pandas, but says his wife knows that full well.

"Sometimes when she talks to me about pandas, I go 'ah', 'mmm'... my ears (start playing) music. She knows (that when there is) music in my ear, I won't be paying attention!"

Would he want his son to join the ranks of the Mandai zookeepers, too? Kumaran is doubtful — after all, he and his wife have both had enough with their own animal-filled careers.

His biggest worry: destruction of habitats

Photo by Ng Yi Shu

Photo by Ng Yi Shu

Kumaran says his pet peeve with his job, especially after a recent visit to the Wildlife Reserves Singapore-supported Orangutan and Information Centre in Sumatra, is the degradation of the environment and orangutans' habitats that is happening beyond his control.

He speaks of how the wild orangutan population has dropped by more than half during his two decades at the zoo, from about 15,000 to around 7,300, and the sheer expanse of land occupied by plantations.

"It's scary. You could be driving for hours and all you see is oil palm. It's really frustrating that we can't do our part; zoos around the world can't do their part to reintroduce orangutans into the wild because the situation is not stable."

Over the week-and-a-half that he spent there, Kumaran says he witnessed the rescue of a wild male orangutan — the first time he had ever seen one — and accompanied local rescuers in capturing and relocating the ape to denser, protected forests, beyond the reach of deforestation or mass burning for plantations.

"It was a 'wow' feeling; seeing them in the wild is so different because you're tracking, trying to find them, and they will sit (up in the trees) until you can't notice that they are there... (but on the whole) it was a good experience and a good eye-opener, (and it made me) appreciate what we have, and thankful for what we have back home."

Another thing that makes him sad: sending orangutans away, which they do for other zoos abroad to assist with breeding. Since he joined, he says has sent off four, while the zoo has sent orangutans to zoos in more than 10 countries including New Zealand, Australia, India, Malaysia and Sri Lanka.

Kumaran remembers Veera, the first orangutan whose umbilical cord he cut in October 2000, whom he sent off to Taiping on a long-term breeding loan, where he will stay and impregnate the female orangutans living there.

"I still keep in contact with the vets so they will send me photos. And he (Veera) has four females there, so he's a lucky guy. The first day he arrived, second day we mixed him with the two females, and he was already showing signs of wanting to get lucky!"

Photo by Ng Yi Shu

Photo by Ng Yi Shu

Till today, after all his experience and his great fondness for orangutans, Kumaran still loves snakes very much, and is happy to help his reptile department colleagues in the event there might be a case of snakes on the loose.

Asked if he would be able to share his skills and love for the animals with future young keepers, he shakes his head sadly — perhaps with the unspoken awareness between both of us that talent renewal in the zoo will be a challenge in the years to come.

"I don't think you can learn this kind of thing... certain things you can't teach people... it has to be in them."

Top photo courtesy of Wildlife Reserves Singapore.

Keen to read more of Mothership.sg's Almost Famous series?

Almost Famous: The real story of The Real Singapore

Almost Famous: The Real Singapore couple on love, their Ramen stall and Tin Pei Ling

S'porean Navy scholar with computer science degree makes mark in international pop music and EDM

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.