This is Dr Chia Thye Poh.

Over the weekend, it was announced that he has been nominated for the prestigious international Nobel Peace Prize by Singaporeans First chief Tan Jee Say and Bangkok University professor James Gomez — four days before the winner will be announced on October 9.

He's up against some 272 other candidates and organisations, though — these include German chancellor Angela Merkel and Japan's Article 9 society. Gomez and filmmaker Martyn See had sent in their nomination letter in January, while the Nobel committee shortlisted the nominees in May.

A former member of parliament for the now-defunct Barisan Sosialis, Chia was arrested under the Internal Security Act in 1966, and was only released 23 years later in 1989 — making him the second-longest serving prisoner of conscience after the late Nelson Mandela. He then went on to spend 9 more years under severe restrictions, which makes his total length of incarcerations and restrictions longer than what Mandela endured.

So what's the deal with this guy, and why are people nominating a longtime political prisoner for the Nobel Peace Prize? We share six interesting facts about him:

1) Chia was elected MP of Jurong in the 1963 election, at the age of 25, winning a four-cornered fight

Apart from all this, he also garnered a decisive 55.85 per cent of the valid vote.

We should add, though, that four-cornered fights were common during that time. In fact, at the 1963 polls, nearly every seat (and the acronym "GRC" didn't exist yet, #justsayin) faced a four-cornered fight.

Chia’s party, the Barisan Sosialis, was one of the more dominant ones in the opposition at the time. Its charismatic leaders like Lim Chin Siong and Lee Siew Choh made the party popular among unionists, rural people and Chinese community, after splitting from the People’s Action Party.

The PAP back then can also be said to have been at its weakest, and GE1963 was widely considered to be the ruling party’s most bitterly-fought General Election.

Chia took charge of his constituency in both the Legislative Assembly in Singapore after the election, and represented Singapore in the Dewan Rakyat (the "House of Representatives", at the lower house of their Parliament) of Malaysia, until Singapore’s split in 1965.

2) He and several others boycotted parliament in 1965

Shortly after Singapore’s independence (and separation from Malaysia), Chia and his fellow Barisan Sosialis members boycotted parliament to protest the ‘undemocratic acts’ of the then ruling PAP. He said the issue wasn't raised with Parliament before the decision was made, and without consulting the populace.

“There was no referendum. We protested and asked for a convening of Parliament,” Chia told the South China Morning Post in a 1998 feature.

3) As an MP, he was tangled in many law suits and court cases

Posted by Martyn See on Saturday, 16 November 2013

Before his arrest in October 1966, Chia was:

- Sued for libel by Yap Bor Lim, then chairman of the Nanyang University Students’ Fellowship, in September 1964. He had to pay Yap $5,000 in damages, which was reduced to $3,000 after a published apology.

- Charged with sedition for claiming in an op-ed published in the party's newsletter The Barisan that the government had plotted to murder Barisan Sosialis's secretary-general, for which he was found guilty and fined $2,000 in April 1966.

- Banned from entering Malaysia after making a political speech in Perak at a conference for the Labour Party of Malaya in April 1966.

- Charged with unlawful assembly and fined $500 for demonstrating against the US participation and bombing in the Vietnam War in July 1966. He chose to go to jail until Barisan paid the fine for his release.

- Right before his arrest, in October 1966, he led an illegal protest march to Parliament House and demanded that a general election be held with the release of political detainees and repeal of ‘undemocratic’ laws.

4) Chia was detained for so long because he refused to sign a forced confession, which would have implied that that he was a violent communist

The confession of guilt was a declaration that he would renounce violence and severe ties to the now-defunct Communist Party of Malaya, and Chia refused to sign it because "to renounce violence is to imply you advocated violence before”.

"If I had signed that statement I would not have lived in peace,” Chia had said.

Internal Security Department officials once asked Chia’s father to persuade him to sign the confession in the mid-1980s. Chia’s father was brought to the ISD headquarters, where he was shown two statements — one an unsigned confession of guilt and another to renew his detention for two years.

When Chia met his father, he pushed the confession aside and told the officials off: "You should not have done this to my father. You are taking advantage of an old man."

On other occasions, Chia would be driven around the fast-developing Singapore, in a bid to tempt him into signing the confession. Chia would reply, "It's clean and it's green, but if life is so beautiful, why don't you just let me out of the car to talk to people?”

In his nomination letter, Gomez wrote that Chia’s steadfast resistance to ‘self-incrimination’ in the form of forced confessions from the Internal Security Department was deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize.

“He has over the years been a source of inspiration for those who have taken the hard road of speaking up for political and other freedoms in Singapore – a road still fraught with difficulties and challenges,” Gomez added. "Dr. Chia’s contribution is best assessed for its inspirational political contribution and the energy it affords current activists.”

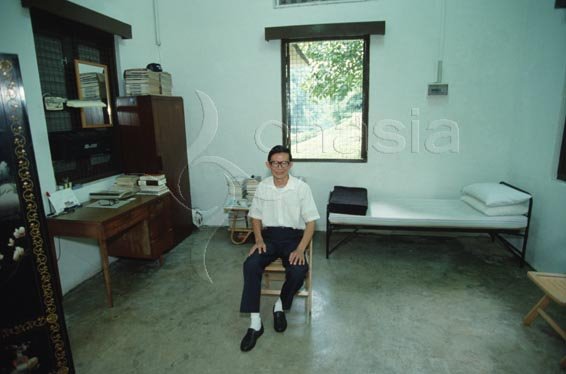

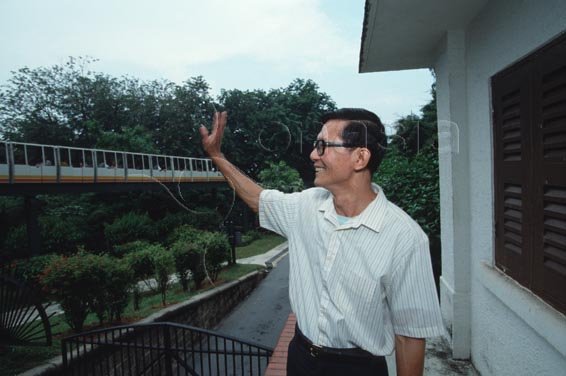

5) Here's what Chia's post-release ‘freedom’ was like:

In his 9 years under various restrictions, Chia lived in a one-room guardhouse around the rapidly developing Sentosa, working as a freelance translator for the Sentosa Development Corporation. He was made to pay rent and buy and prepare his own food, as he was ‘free’.

But under his restrictions, he was not allowed to visit mainland Singapore, travel overseas, change his address or look for a new job until 1997 — nor speak to the media, make contact with political activists or political detainees, or join any society without permission until 1998.

He also declined political asylum in Canada in 1987, which the Canadian government offered, upon the urgent prompting of human rights group Amnesty International. At that time, Singapore underwent another political upheaval as the ISA was invoked yet again to arrest 22 social workers and theatre practitioners in Operation Spectrum.

On Chia's refusal, the Ministry of Home Affairs — then led by S. Jayakumar — said: “It would appear that he prefers martyrdom with the chance of glory if the communist revolution should eventually succeed.”

6) Chia resented comparisons with Nelson Mandela — he was never as ambitious.

“I am not an ambitious man, nor am I a man of Mandela's stature," Chia told the Los Angeles Times in 1999. "Besides, Mandela was at least charged and sentenced to life in a court of law. I never was. But I always knew if I signed that confession I could never live in peace with myself. I had no choice."

He also admitted that he hasn’t achieved much in refusing to cave in. “(Politically), Singapore is more or less the same. The Internal Security Act is still there,” he said. "The opposition is still operating under difficult conditions. So in the end, perhaps not a great deal.”

Top photo: Screengrab from YouTube video.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.