This year, Singapore commemorates the 80th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore and the Japanese Occupation. Over the course of this week, Mothership will be republishing stories that highlight the key events that marked one of the darkest moments in Singapore's history.

Following the events that swept Singapore into World War Two, the British surrender of Singapore to the Imperial Japanese Army marked the beginning of the darkest chapter in Singapore's history.

The stories below are meant to give you a better picture of the brutality of the Japanese Occupation, which wiped out an estimated 50,000 people in Singapore. They feature fictitious characters but are inspired by real-life accounts and actual events that occurred during the war.

Bencoolen Street, Singapore

February 15, 1942, 5.30pm

An uneasy peace had descended on the streets of Singapore. After one week of shelling and air raids by the Japanese, the silence was part relief and part uncertainty. Was the war over?

A charred body stirred on the street.

In its grip, was the day's edition of The Sunday Times, a bleak one-page document singed at the edges. Just right below the masthead was Governor Shenton Thomas' affirmation that "Singapore Must Stand; It SHALL Stand!"

February 15, 1942 edition of The Sunday Times. Via NewspaperSG.

February 15, 1942 edition of The Sunday Times. Via NewspaperSG.

Hours later, the radio delivered dismal news: Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, the commander of the British forces, had signed a document of unconditional surrender, ceding Singapore to Commander of the Imperial Japanese Army, General Tomoyuki Yamashita.

Singapore, the impregnable "Gibraltar of the East" had fallen to Japan.

Changi Beach, Singapore

February 21, 1942, 1.35pm

18-year-old Chen Guang stood shaking uncontrollably.

Behind him, the waves crashed against Changi Beach. In front of him, a line of Japanese soldiers cocked their rifles and took aim in his direction, along with the other Chinese men who were bound together alongside him.

Earlier that day, Yamashita had ordered the elimination of all "anti-Japanese elements" from the population.

The Imperial Japanese Army called it the Dai Kensho (The Great Inspection), but the Chinese saw it for what it was — Sook Ching (肃清), literally "cleansing".

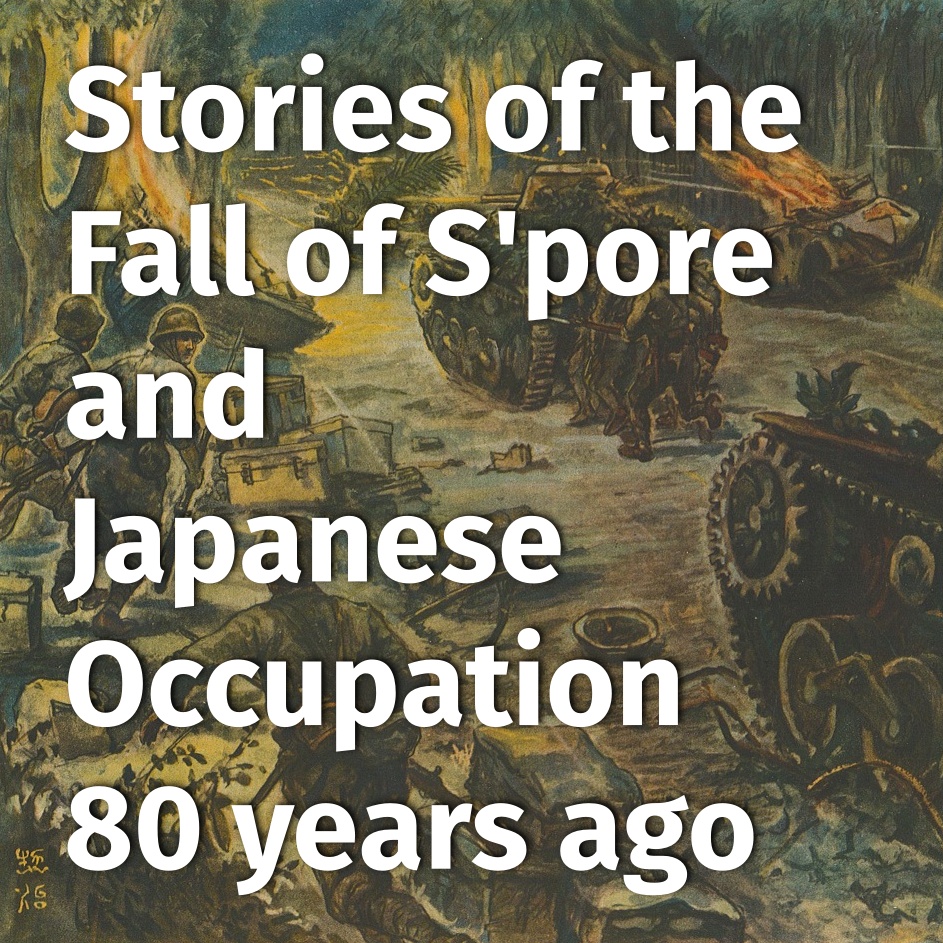

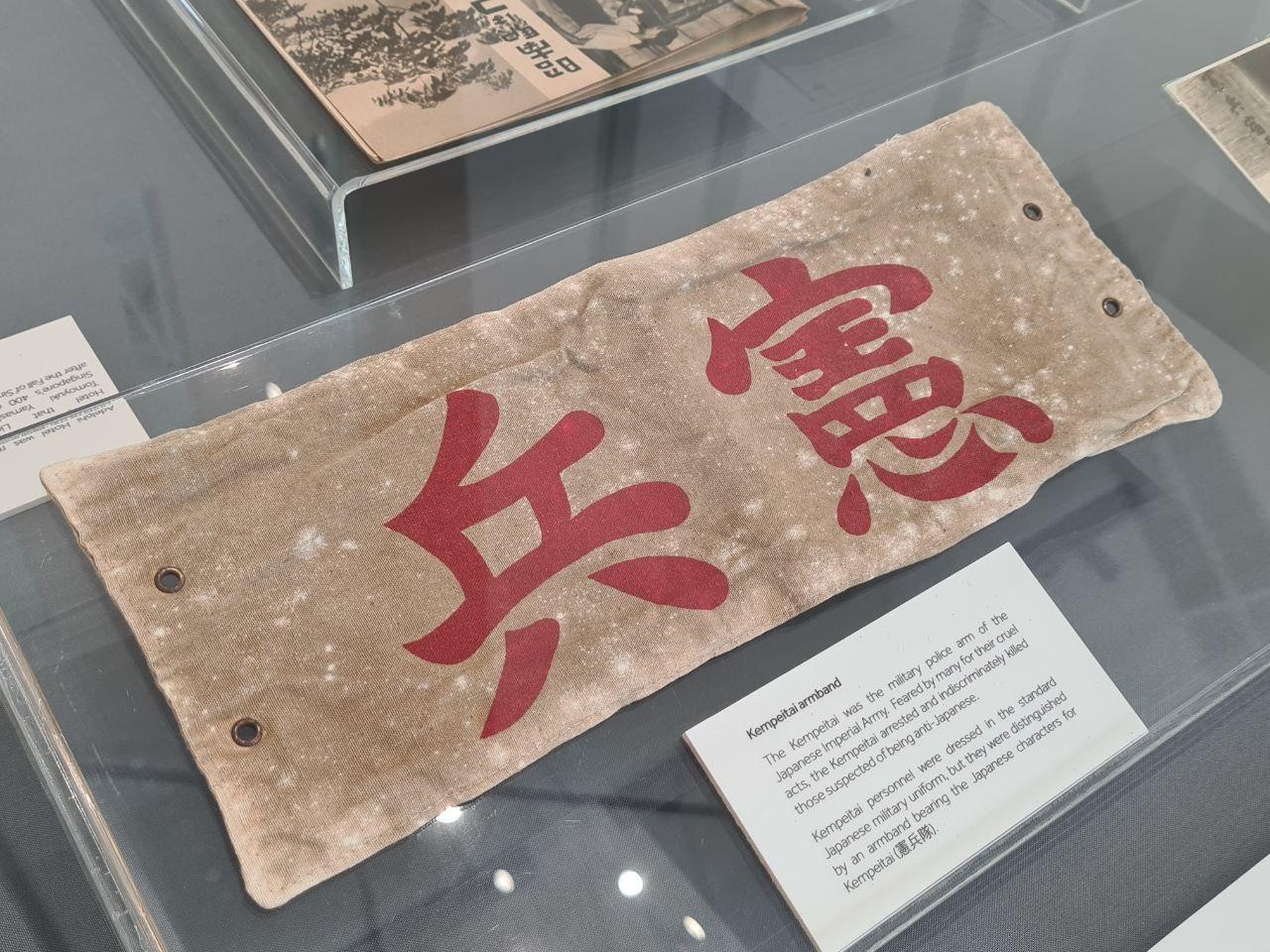

The Kempeitai (Japanese military police) immediately fanned out all over the island, rounding up Chinese men (sometimes women and children too) for screening. Those who did not pass were bundled onto trucks, and taken to isolated locations around Singapore, where they were killed.

Images of Sook Ching screening centres, taken from Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies.

Images of Sook Ching screening centres, taken from Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies.

Without warning, the firing squad opened fire.

A sharp stab to his stomach caused Chen Guang to heave and double over. As he struggled to stand, a second bullet ripped through his neck. Then a third into his right cheek.

By the time he crashed into the waves, Chen Guang was gone.

Armband worn by the Kempeitei. Image taken at the New Light On An Old Tale” exhibition at NAS.

Armband worn by the Kempeitei. Image taken at the New Light On An Old Tale” exhibition at NAS.

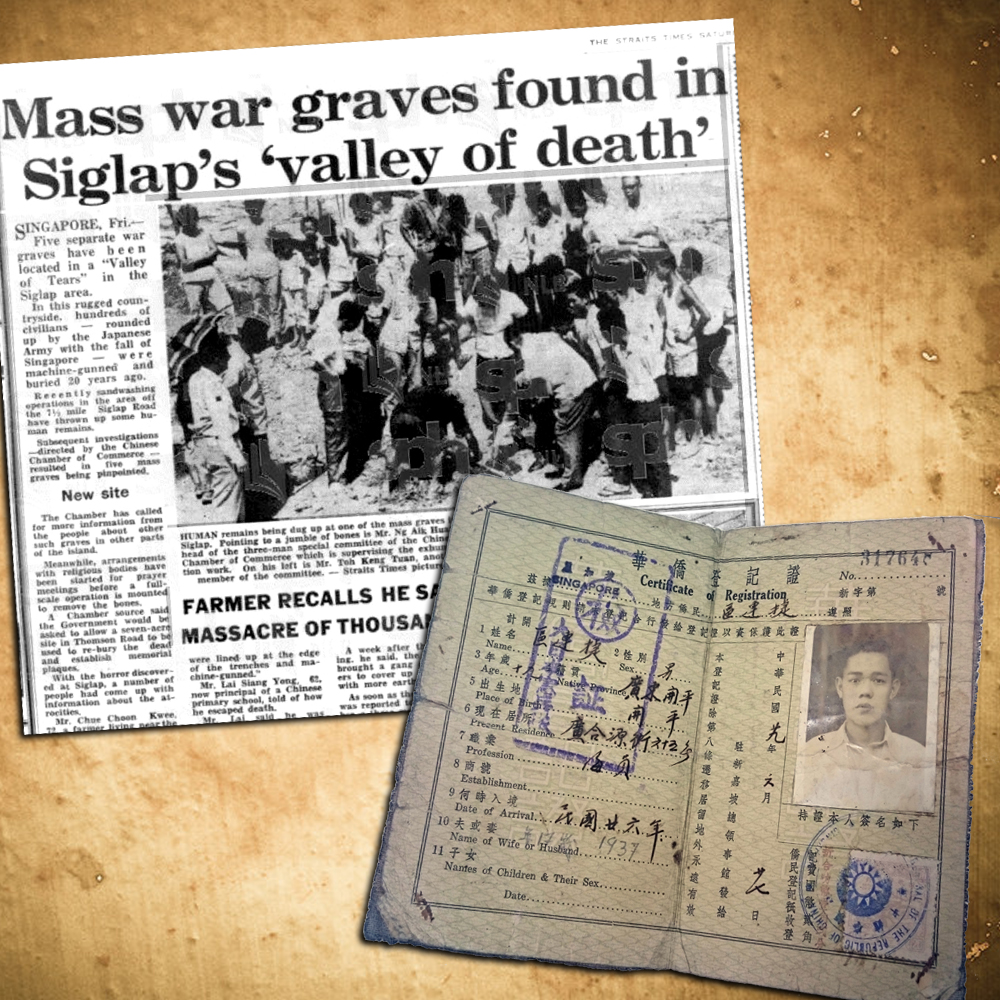

For two weeks, the Imperial Japanese Army went on a killing spree. From Changi to Bedok to Sentosa, mass graves were dug to hide the bodies.

In Siglap alone, there were at least five separate mass graves that would only be uncovered in 1962. The media then christened it the "Valley of Tears".

Those who were lucky enough to pass the Sook Ching screening received either a stamp on their arm or a certificate to prove that they were cleared.

Newspaper article from February 24, 1962 edition of The Straits Times via NewspaperSG and Sook Ching certificate with stamp courtesy of Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies.

Newspaper article from February 24, 1962 edition of The Straits Times via NewspaperSG and Sook Ching certificate with stamp courtesy of Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies.

Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), Singapore

October 10, 1943, 10.30pm

Su Ying gagged as the soldier jabbed the hose further down her throat, forcing her to drink more water. She could feel her stomach beginning to bloat beyond what was humanly possible.

The soldier switched off the water supply. He squatted, bringing his face close to hers, and calmly repeated his question.

"Who have you been passing messages to in Changi Prison?"

About two weeks ago, seven Japanese ships were destroyed at Keppel Harbour, right under the nose of the Imperial Japanese Army. Thinking that it was the work of local guerrilla forces, the Kempeitai rounded up many local Chinese, Malays, and Eurasian civilians, in order to torture them into giving information on who was behind the incident.

Example of water torture during the Japanese Occupation. Adapted via.

Example of water torture during the Japanese Occupation. Adapted via.

"I don't know what you're talking about," gasped Su Ying as water dribbled from her mouth. Her distended stomach pushed against her internal organs, causing her to wince each time she took a breath.

That wasn't the truth.

The canteen that Su Ying worked at was a hotbed for exchanging covert messages and necessities such as food, medication, and even radio parts. She had often slipped radio transmitters into food deliveries for the prisoners of war at Changi Prison.

In a fit of rage at her response, the soldier rammed his boot into her stomach. Su Ying's cries of pain were drowned out by the water that gushed out of her mouth, nose, and eyes.

A "blood debt"

The atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese Army extended beyond these.

Korean, Chinese, Indonesian, and Malay women were taken to serve as prostitutes at comfort centres in places like Cairnhill Road, Jalan Jurong Kechil, Tanjong Katong Road and Teo Hong Road.

There are also accounts of Japanese soldiers lashing out at children on the street and slapping adult civilians who didn't bow to them.

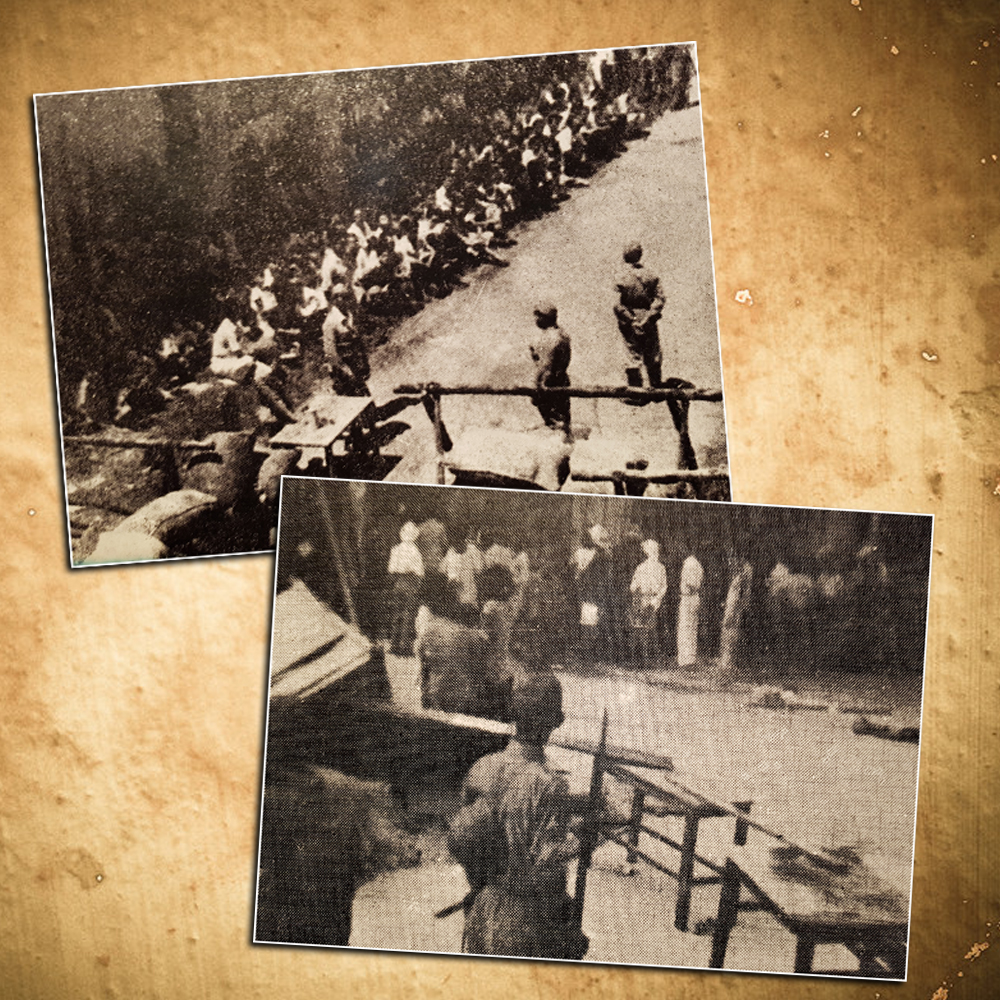

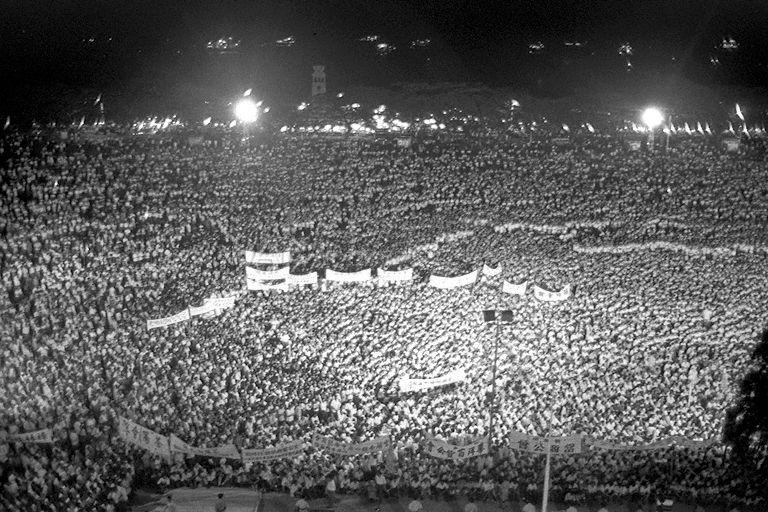

One year after the mass graves were uncovered at Siglap in 1962, more than 100,000 people rallied at the Padang demanding compensation for the "blood debt" that the Imperial Japanese Army incurred.

The turnout at the "blood debt" rally. Via NAS.

The turnout at the "blood debt" rally. Via NAS.

Over the years, various Japanese prime ministers have expressed their regret and apologised for war crimes committed by Japan during World War 2. However, for many older Singaporeans who suffered through the war, it is a debt that cannot be repaid.

If you would like to find out more about the Japanese Occupation, the National Archives (NAS) is currently holding "New Light On An Old Tale”, an exhibition that showcases artefacts from three private collections.

The exhibition, which is held at Level 3 of the National Archives building (map), runs from February 15 to June 30.

Top photo features a quote from a survivor of the Japanese Occupation. His oral history interview (Accession Number 000374) can be found at the National Archives Online. This article was first published with the headline "Becoming Syonan-to: The brutality of the Japanese Occupation from 1942 to 1945" in 2017.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.