Professor Yaacob Ibrahim begins his days bright and early at 4:30am in prayer with the Quran.

These days, in fact, he structures his days around his prayer time — optional prayers at roughly 4:30am, morning prayers at about 5:45, post-lunchtime prayers, the 4:30pm evening prayer, plus of course the 7pm and 9-plus pm rounds before he turns in for the night by 10pm.

He counts the ability to do this as a luxury he certainly did not have just three years ago, when he was still a Cabinet minister — or even up to last July as a backbencher, when he sat out the Singapore General Election for the first time in 23 years.

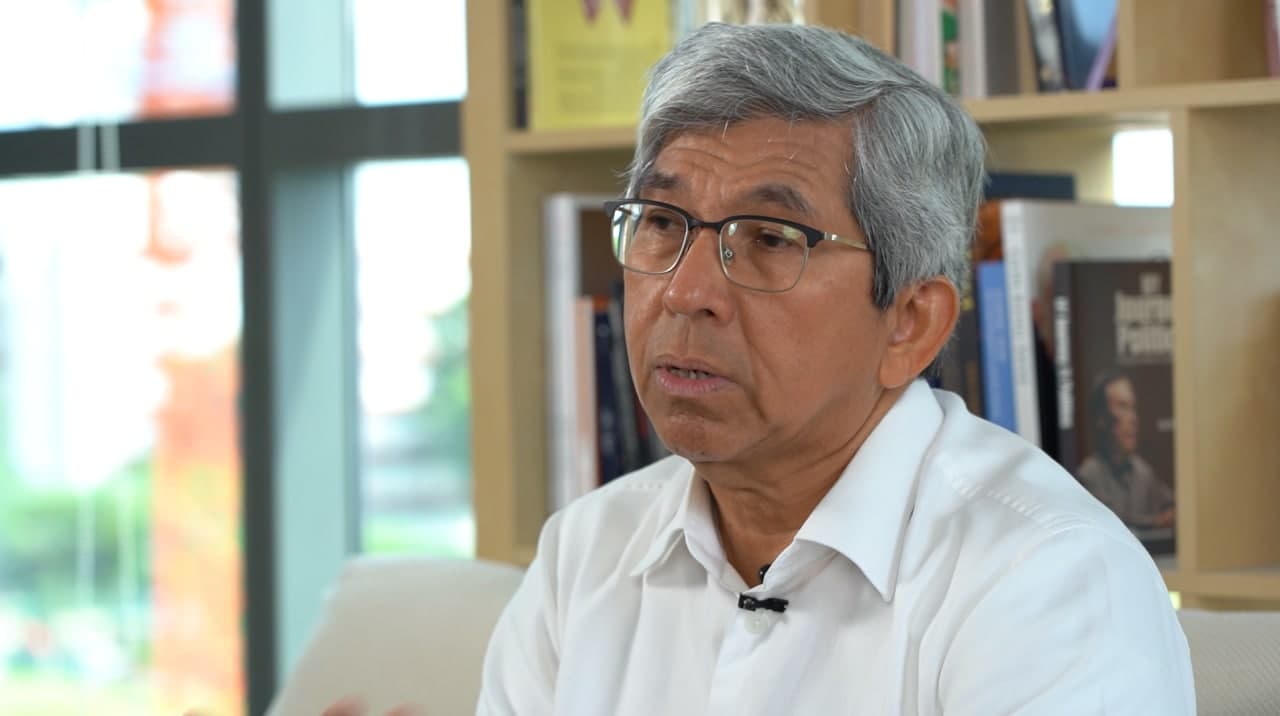

The 65-year-old is one of Singapore's longest-serving Ministers-in-charge of Muslim Affairs, having held the position from 2002 to 2018 — one that for him carries particular significance, challenge and meaning.

On the day we meet him, he arrives at our office unaccompanied — no minders, no ministry staff hovering around, the chief reminder to me to avoid calling him "Minister" — and we sit down to chat about what he's been up to, look back on his life and take stock of the sacrifices he made and struggles he faced on the way.

The first thing we talk about is family.

Friendly competition

Despite his protestations and insistence on calling his family "average", Yaacob has to admit that he and his eight siblings are leading immensely accomplished lives.

We know that his oldest brother, Mohd Ismail Ibrahim, is Singapore's first Malay President's Scholar, clinching the award in 1968. His younger sister Zuraidah is a noted veteran journalist and editor now at the South China Morning Post, and another sister Hamidah is a State Court judge.

All in, the Ibrahim siblings consist of three lawyers, an engineer/academic-turned-(now retired) minister, a senior editor, a court judge, a teacher, a Monetary Authority of Singapore banker and finally a surgeon. Whew.

He jokes that Mohd Ismail took all the brilliance while the rest had to share the "remnants", but he believes that after his parents saw him constantly coming in first in class, they encouraged an atmosphere of friendly competition and so everyone worked hard to attain their respective best achievements.

Political watchers and general kaypohs (like me, I suppose) would also know that one of Yaacob's brothers-in-law happens to be journalism professor and public intellectual Cherian George, who is married to Zuraidah.

Which, when everyone was back in Singapore (George and Zuraidah are based in Hong Kong now), made for fun Sunday family dinners where "nothing is off the table", including politics. The prof admits to having "crossed some swords" with his brother-in-law on occasions, and dodged attempts at extracting insider information from his sister.

"All part and parcel of the conversation," he says with a smile.

Missed out on his own family

Yaacob's work family when he was MCI minister. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob's work family when he was MCI minister. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Which turns us to his own family — the one he started with his wife. Over the years, there were murmurings online about Yaacob's two children living and studying in the U.S., but he confirms they're back in Singapore now. Yes, his son, who is 26 this year, has served NS; his 24-year-old daughter works part-time here with the National Library.

We got round to talking about this when I asked him if his routine makes him happier these days, now he has a lot more time on his hands.

"Well, it is (happier these days). But it is also not.

It is because you don't have all this exigencies of duty — night calls and all that. It is not because your kids are grown. Those years when they were growing, you were not there. Right?

People forget that, you know, yes, I have more time, but your kids will say, why are you at home? They're so used to the fact that you were not at home, right.

So I suppose there is a price to be paid. It would be remiss for me to say that it is a walk in the park. And then when you retire... no, your kids have grown, they have gone."

It's a sacrifice one makes when entering politics, Yaacob says quite matter-of-factly. No one can run away from it — but that was the reason it was so important that he got his wife's buy-in before saying yes to the call, first from then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong (to whom he initially said no) and subsequently from then-minister Abdullah Tarmugi (when he was eventually ready to say yes).

His method of coping was to make it a point to be home for dinner with his family every day. That, followed by his evening prayers at home, and then he's back out for his MP duties at night.

He would also take advantage of morning drives to school to catch up with his children as they grew older, and additionally took at least one family trip overseas a year together.

Answering the call — and saying no to Goh Chok Tong

So why'd Yaacob say no the first time he was called for tea, back in 1990? He explains that the truth is, he didn't want to be parachuted into a place he had no idea about.

"So I got a call from the Istana. Goh Chok Tong just took over, and invited me to lunch with him. I was stunned! I remember being there at the lunch table — myself, Zainal (Abidin Rasheed) and at that time was PM Goh.

After the lunch PM Goh said, here's a form. So I went back and thought about it, discussed with my wife and I wrote him a letter saying I'm not ready.

Because I suppose you know, in one way, I believe that if you want to be an elected representative, you must know the community that you're representing, you must know what's going on. I've been away in the States for seven, eight years. I mean, at that time, there was no internet, you know, newspapers were very slow in coming, and you don't know what's going on. And to come back and plonk yourself here, and become this MP when I don't know what's going on? I felt it wasn't right, basically."

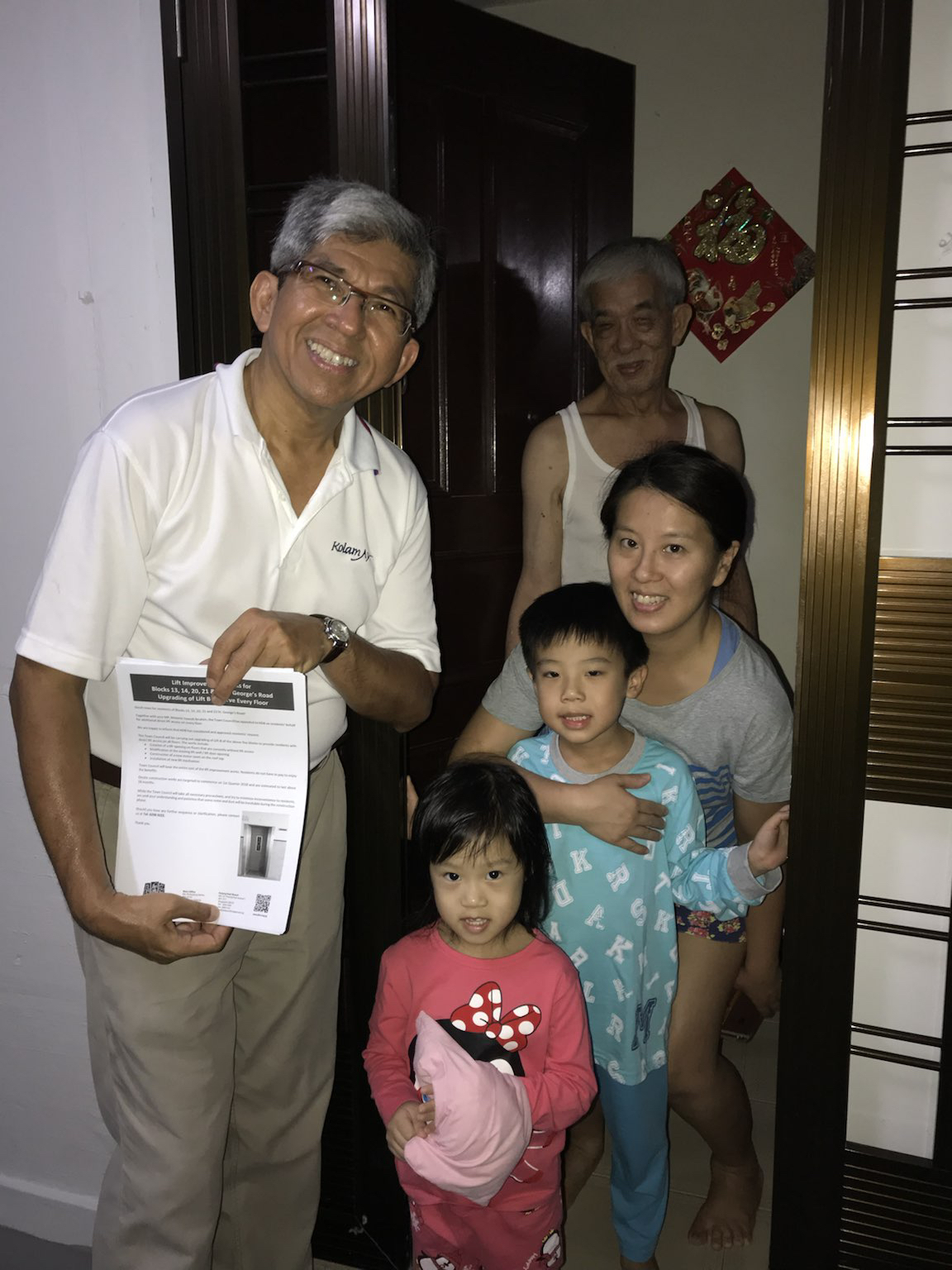

He would, of course, eventually dive headfirst into his Kolam Ayer ward, where he was sent to replace senior MP Zulkifli Mohammed, and would continue serving there for many years:

Yaacob visiting a home in Kolam Ayer. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob visiting a home in Kolam Ayer. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob at a stall at Blk 17 Upper Boon Keng Cooked Food Centre. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob at a stall at Blk 17 Upper Boon Keng Cooked Food Centre. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

By this point, Yaacob had already joined MENDAKI as a volunteer (this being from its founding years), and also had a seat on the MUIS council. What he decided, in this regard, was that he must first understand the Malay-Muslim community in Singapore better, and read up on its history, challenges and issues that were of concern to them.

And it would eventually be this enhanced understanding and empathy Yaacob developed from embedding himself in the Malay-Muslim community that would push him to say yes to his second call, become a politician and later on a minister, to do everything he can to advance and uplift them as a whole.

"Anyone who joined the PAP was considered a traitor"

When I spoke to Aljunied GRC Member of Parliament Muhamad Faisal Manap back in 2018, one thing that struck me from our conversation was the burden he shouldered as Singapore's sole opposition Malay-Muslim MP.

My conversation with Yaacob helped me to realise that it wasn't much easier being on the side of the establishment, sadly.

He recalls the sentiment of distrust with the government several Malays had in the late 90s, when he first entered politics.

"There are some people who said, Why do you want to join them? You know, they have treated us badly, national service and so on and so forth, right... there's always this view that the party may not have been fair to the (Malay-Muslim) community. That is a backdrop that we cannot sweep under the carpet.

So one of the biggest challenges any Malay MP faces now, and even during my time, is to build that trust within the community and the government. I took it upon myself as something that I wanted to do."

The great struggle of being Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs

Yaacob as Minister-in-Charge of Muslim Affairs with students outside a mosque in Turkey. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob as Minister-in-Charge of Muslim Affairs with students outside a mosque in Turkey. (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

And what did "badly" mean? Yaacob doesn't hold back — listing the widely-known but rarely discussed (out loud) phenomenon of young Malay-Muslim men enlisting for national service and then being assigned to the SCDF, or relegated to a vocation as a clerk instead of Officer Cadet School.

The latter scenario, incidentally, happened to him.

"I was the first in my family to go to full-time NS. But I was relegated to clerk service, you know, when we have aspirations to be army officers and so on. So I think I don't want to gloss over that.

I still had residents coming to me, asking why does my son join the army and get thrown into the Civil Defence? Real questions. How do you answer those questions, you tell me? I myself experienced some of those things when I was doing my national service...

This is something that you have to deal with, because this is your community... you are part of Singapore; how do you ensure that integration takes place, right? That was one of the things that was also on my mind when I came in because I knew there was also an expectation for me to make sure that I can protect the community and our community interests."

And if that's not enough, this is where the party he belongs to complicates matters a bit:

"Yet at the same time, I know that I'm not just a Malay MP, I'm also a national MP; how do we ensure that the national agenda is also adopted by the Malay community? And the community was divided, I have to tell you that...

So this is something I think people need to recognise; I went through that. And also because I think you grow up recognising that these are some of the challenges that your community face and you cannot ignore it."

Yaacob recalls, in fact, that the year 1976 saw a group of Malay students who sought an audience with then-Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee to ask why Malays were not called up for national service — which, Yaacob says, was a situation that impacted their employability.

And so the implications of this unspoken discrimination go beyond NS too, as most would be aware:

"You hear stories about Malays not getting a job because they are discriminated. Malays cannot go to the police force or the army because, you know, they're all dumped in civil defence. I got people in MENDAKI telling me this, you know.

I don't want to brush this aside. It was a very painful exercise because you just, you know, wake up thinking, why is your community cast that way, right? And yet we have been loyal, we have contributed. It's an area that I want to see things improve."

Why Yaacob entered politics: to help uplift his community

Now all this being said, Yaacob certainly acknowledges that things have improved. Malay army officers are far more common these days — even his younger brothers had the opportunity of better vocations during their time — perhaps what the community is waiting to see next, he says, is a Malay naval officer or pilot.

While Yaacob recognises that Singapore has a Malay President (Halimah Yacob), he mentions the need for leadership representations in more sectors of the society.

"We were looking for Malay permanent secretaries, Malay directors, you know, because then you have a complete community."

And what is a complete community? Yaacob refers to an example his wife refers to in the Black community in America.

"Yes, they are overrepresented in (criminal activities).... But they have expressed the ability in other areas, basically. So that's something which I think we should be thinking about, you know, for, for the community and how we can move forward too.

I mean, I'll be honest about it — I also joined politics to find a way to help my community. I will not deny that. I wouldn't want to put it crudely that Singapore doesn't need me because there are brilliant Chinese out there as ministers. But while I know I'm there as a minister to contribute to Singapore, at the same time, I must also do something for my community."

The added role Malay MPs have for their community

Yaacob with MP Rahayu Mahzam, Rahayu Mohd (past president of Singapore Muslim Women Association) and Rahayu Buang (then-CEO of MENDAKI, current director at ECDA). (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

Yaacob with MP Rahayu Mahzam, Rahayu Mohd (past president of Singapore Muslim Women Association) and Rahayu Buang (then-CEO of MENDAKI, current director at ECDA). (Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim)

It is here that he, too, touches on the unique responsibility Malay MPs have on behalf of their community, by virtue of the positions they have been elected to.

"So whenever I meet young, aspiring MPs, I say don't forget, you have three constituencies — your Malay ground is very important. And if you cannot deal with the Malay ground, frankly speaking I say you are useless to the party.

Because the Malay ground is a very important ground, it is part of the landscape — we are 15 per cent. And we must make sure that the 15 per cent don't feel that they are alienated, they are marginalised, that they don't have a place in Singapore. Right? So I saw that as something I wanted to do when I entered politics."

Has he succeeded?

But here's the big question — has he succeeded in making inroads into greater representation and equal treatment for the Malay-Muslim community in his 16 years as Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs?

He explains that because of when he entered office (March 2002), in view of the air of suspicion around the Muslim community here continuing to hang heavy in the wake of the September 2001 terror attacks, his main focus in the early years was to make the Muslim community as much a part of Singapore as possible, instead of a distinct one by virtue of their religion.

"I mean, you know, we are distinct in some ways because of our certain beliefs, but we are also still Singaporean. So I wanted to continue to emphasise both for the Malay community to see themselves as Singaporean and for the other members of Singapore, to see the Malays as Singaporeans."

He notes that 9/11 was also an opportunity for him, and Muslim authorities here, to start learning to explain the tenets of the Islamic faith to non-believers — something that was never done before.

But indeed — Yaacob shares candidly with me that "history will have to judge" whether or not he succeeded in making progress with respect to Malay representation and equal opportunity in our military and other areas of our society.

"... the community will always say, you're not doing our bidding, you know, you're not pushing for us... There's so much that you can do, and try your best. I'd like to believe I have done my best, but I know that I have critics out there who feel that I failed them. And I have to live with it. It's a fact of life.

I knew when I joined politics and eventually became a minister, that it was not going to be a walk in the park. But I'm a religious person, and I see this as an opportunity that God has thrown my way, for me to try and make use of the opportunity to the best of my ability too. Not just help the community, but to do the best you can to improve Singapore, right. That's what you are also there for."

Many matters and allegations of discrimination and deliberate elimination of Malays, especially in the military, are not provable and remain as anecdotal complaints, he notes.

While he has on many occasions made representations in many meetings involving the relevant parties over the years, echoing his aspiration for greater representation, what he ultimately says is "it wasn't easy".

"I was always looking for opportunities to get more Malay representation in these uniformed services. And, you know, how shall I put it? In a way, you can't force the issue. You hope it happens, you express those desires, candidly, in some of the meetings. Because I'd be honest, I don't believe that the Malays are less capable than the other communities and doing so is wrong.

I stand from the belief that Malays are as capable as any other community to do the job. Give them the opportunity, and I think they will rise to the occasion."

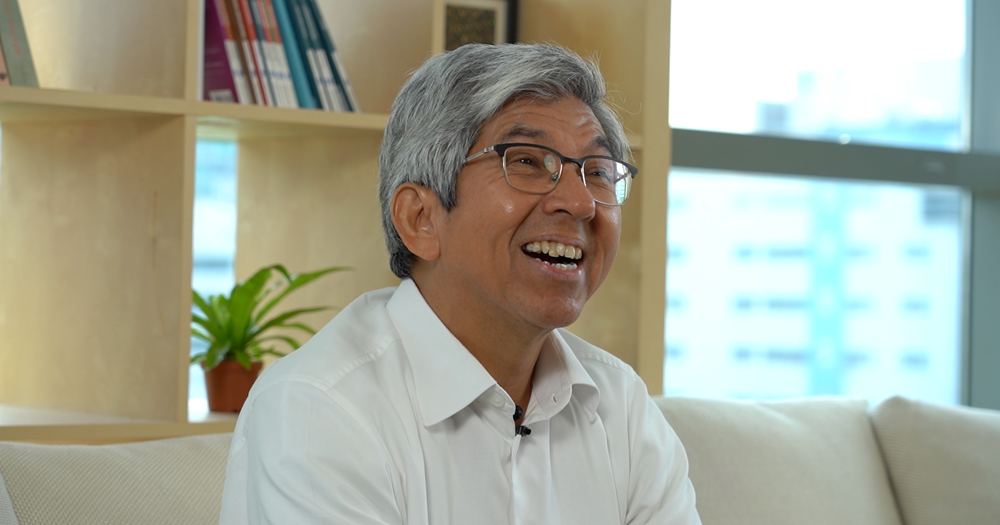

An experienced leader with more to offer yet

Photo by Angela Lim

Photo by Angela Lim

It is this passion with which he speaks about what he set out to do to support Malay-Muslims, as well as other initiatives he spearheaded as an MP and minister, that gives one a feeling that he does not want to retire from public service yet.

Today, he is director at the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT)'s Community Leadership and Social Innovation Centre, as well as advisor to SIT's President.

In the former role, he raises funds from his vast network to support ground-up projects and initiatives harnessing design thinking from groups of engineering and design students whose teachers send them to the centre for service learning. These projects are done in partnership with specific external organisations to directly help their beneficiaries.

He says he cherishes the opportunity to bring his network and ministerial experience to work at SIT, an institution that is unique in its student make-up — 45 per cent of them are on social or financial assistance, and one out of every two graduates is the first in their family to graduate from a university.

Yaacob finds so much meaning from this as an engineer and academic that in the years before he bowed out of politics entirely, he found himself implementing short design thinking and tech-skills-based courses for his grassroots in the Kolam Ayer ward at their yearly overseas retreats.

At SIT, he also works closely with former Malay-Muslim MP Intan Azura Mokhtar at the centre, whom he says "does all the heavy lifting", while he goes out to find projects and also garner the funds needed for them.

So to the big question: Why stay on with the PAP?

Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim

Photo courtesy of Yaacob Ibrahim

So why stay on with the party after stepping down from its leadership — Yaacob last held the post of vice-chairman — and retiring from politics?

Yaacob says if he were to leave the party after stepping down, it would have made his presence in it "transactional".

"Should it be that I join it because it's convenient; when I'm out, I resign? No. I believe in the party. I think the party has done a lot of good for Singapore. I may disagree with some of the policies like anyone else. But by and large, I think it's a party that's worth supporting. So why should I want to resign?"

He explains also that despite not having a formal role in the party, as a member he is also consulted over various policy issues and matters, and participates in these discussions and feedback sessions actively. As a former minister who was part of the party's leadership, he also appreciates the opportunity to reach out to members of current leadership with his feedback or concerns directly, with the knowledge that his feedback will be heard.

"I think you have to hold true to what you believe, basically. But at the same time, you're part of the party. Unless the party is doing something that egregious that's a different matter, then you say, no, you have crossed my value system, then I have to do something about it.

But I think the PAP is not doing that. And I hope we'll never do that. And you know, they are a party that is trying to be as progressive as possible, because you want to plan for the next phase of Singapore's development. I think that's the right thing to do."

And ultimately, perhaps, the conclusion of our conversation probably sheds the clearest light on why he's still sticking around and voicing his opinions:

"I retired from parliamentary politics, but I'm not retired from politics. I have a stake in the future of Singapore because of my children. Right? I mean, where else are they going to go — they are Singaporeans, they carry the red passport — if this country goes down, where can they go? So we have to make it succeed."

Top photo by Hor Teng Teng

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.