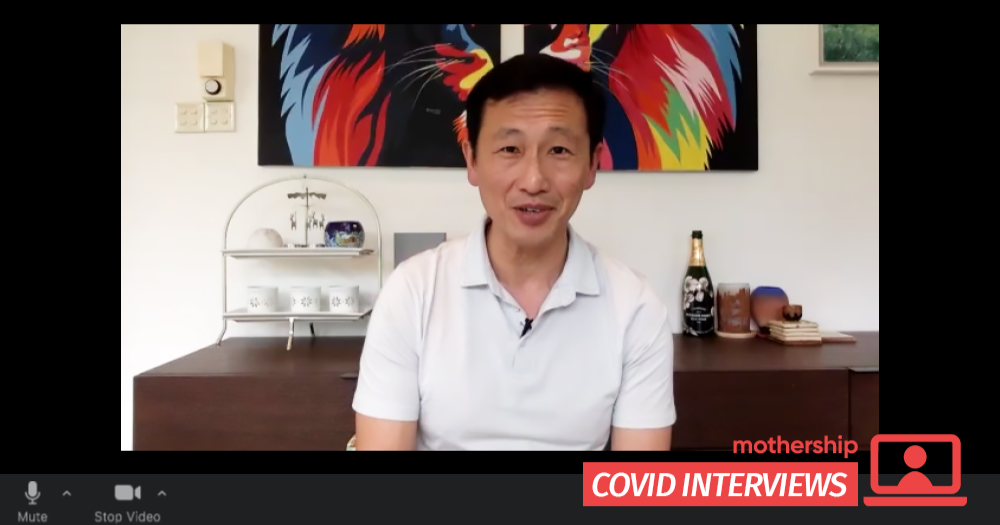

It's a Sunday morning and we're in a Zoom call with Education Minister Ong Ye Kung.

How was the first fortnight of schools reopening? "Bad"

We're at the tail-end of the second full week of schools reopening at Phase 1 of Singapore's exit from the Circuit Breaker period — which means all school-going students whose academic terms were in session would have attended class for at least a week.

This also makes it a good time for us to ask him — how'd the reopening go, from his perspective? His response, unequivocally, was "bad".

On Week 1, four students and one staffer tested positive for Covid-19.

"So when it was reported to me, immediately I prepared for the worst — If it is a cluster within a school, we might have no choice but to close the school."

To close affected schools or not? Inside the decision-making process

Following his thought process was a bit like seeing him mechanically go through a mental flowchart:

How many schools? Five different schools → Okay, not a cluster. There's a chance we don't have to close the schools. → When were they infected? We needed to fact find. They were PCR (polymerase chain reaction) positive. → They did serological tests (which detect antibodies to the virus in your blood, suggesting that your Covid-19 infection is old). → All five negative: bad news.

"I need to ascertain, did they get it in school? If yes, it's more serious. It means that maybe our safe management measures have been breached."

But two days later, another development: all five tested negative for Covid-19 within days of testing positive.

"And based on that evidence, MOH (Ministry of Health) was quite confident that these are old cases, otherwise you won’t turn negative so fast. What’s also important was that MOH then informed me that their CT [or cycle threshold] value was high, which means their viral load was low. They were borderline positive."

Two conclusions were drawn here: 1) they were infected toward the tail end of Circuit Breaker, and 2) they were not infected in school.

"And then when we look at the schools, and all of them have taken their safe management measures very seriously, we decided, there's no need to close schools.

But in the process, we issued Leave of Absence and Quarantine [Orders] to about 100 students and 30 teachers. So they're all doing HBL now. They are well and we expect them to come back to school next week."

And that was that.

Week 2's case was more straightforward — she tested positive in both her PCR and serology tests, which means hers was another old case (not infected in school).

Her close contacts were quarantined or given LOAs, and the school was given clearance to reopen for Week 3.

Clear, direct communication with parents, based on data

The certainty with which Ong speaks about these challenges his ministry faced belies the immense pressure exerted on him on a wide range of concerns and questions bombarded at him by parents: why test only preschool staff proactively and not all school staff? Why start school again when community cases are not yet at zero?

These were among a range of similar questions he and the MOE received from parents (pro-tip: he reads all his email and FB DMs too, but not as much the comments in his posts, by the way) that he distilled into candidly-worded posts on his Facebook page, arranged as a list of the top three frequently-asked questions (FAQs):

"FAQs are not three things that the ministry wants to say. FAQs are three questions that people have in their minds and would like you to answer and if you don’t have an answer say ‘sorry I don’t have an answer yet, I'm working on it', and I think people will appreciate that."

Here's one of his earlier ones when the reopening of schools on June 2 was announced, for instance:

And here's a more recent FAQ post from him on the return of all students to schools on June 29:

Ultimately, though, his overriding concern is clear: opening schools as quickly and safely as possible (because closures affect the needy the most, he explains), based on the concrete figures available."Your decision must be based on the data, the facts. Then decide accordingly."

The foreseeable future of CCAs in schools

We also dwell on the unpopular decision (among students, at least) Ong's had to make so far against allowing most CCAs to resume as they used to be, despite them being, as he says, "the highlight of our children's childhood".

Ong tells us his conversations with students often include exchanges like the following:

"You ask every kid: ‘Do you love going to school?’ They would say, 'Yes'.

‘Which part you like?’ ‘CCA’.

‘Which part you don't like?’ ‘Exams’."

Even while CCA and other non-classroom activities look set to return gradually, Ong seems keen on the opportunity to bring them back in a different and more inclusive way.

Ong previously referred to Covid-19 as "a big reset button" for the economy in a virtual graduation ceremony earlier this year.

In the same vein, he sees a silver lining behind the safe distancing measures, in that they could temper excessive inter-school competitiveness in CCAs, especially in areas like sports:

"Certain schools are just so strong, and others are just totally decimated. So, that is also not quite the spirit of competition that we are promoting as part of education."

After all, "we really should let children play", especially at the primary and secondary school level — a simple enough objective that, Ong says, had been on MOE's agenda for some time.

Personal development, CCAs, and CCE

Beyond play, CCAs and other activities will also be important for Character and Citizenship Education (CCE).

At the Committee of Supply debates earlier this year, Ong announced new initiatives which would see CCE being integrated into school lessons and activities, including CCAs, camps, cohort learning journeys, and Values-in-Action.

"If we can bring [CCAs and activities] back in a safe way, it means a lot to the children. And indeed, it is important for their holistic development".

Gearing the emphasis in schools towards holistic development, often juxtaposed against academic development as being mutually exclusive, has been on Ong's mind even before Covid-19.

"Academic learning is important, but you have your whole life to learn. And so, is it that important to front-load so much? I think the conclusion is ‘no need’."

Changes to the school system accelerated by Covid-19

This leads us to the broader topic of changes to the school system, many of which had been in the works even before Covid-19. Ong says:

"In the longer term, we will fully implement the many changes made to the school system. I would summarise it as: the change is actually driven by the philosophy of SkillsFuture.

Our children are different - different talents, different aptitudes, and the system must encourage it and develop them through different pathways. That is the essential push."

Covid-19, he says, "did not put a stop to that change", but rather provides impetus to accelerate it.

"How we overcome this crisis is a function of our agility. The diversity of our economy, mobility of our labour force.

And that starts from school, and that's the direction we are moving towards."

SkillsFuture, its origin & relevance

You might be wondering how Ong was able to make a link between changes to the school system and "the philosophy of SkillsFuture".

Our guess is that it has to do with his previous experience as the Chief Executive of the Workforce Development Agency (WDA) from 2005 to 2008, a role in which Ong was, in his words, "very active".

WDA has since been reorganised into two statutory boards; Workforce Singapore (WSG), and SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG).

SkillsFuture actually dates back to 1997 (and perhaps even earlier)

Which is why Ong is able to speak at length about how SkillsFuture, the national movement launched in 2016, actually dates back to 1997, and possibly even earlier.

He recalled how former Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say, as the Labour Chief, kick started the Skills Redevelopment Programme to retrain the retrenched workers, and that planted the seeds for SkillsFuture to grow further.

The long tradition of our SkillsFuture movement, Ong supposes, is what PM Lee means when he referred to SkillsFuture as one of the reasons why Singapore's economy has a "head start" in preparing for the uncertainties ahead.

Both in terms of competing with other economies, and competing with ourselves. And in that latter sense, our current "head start" is in being able to ensure "we can survive and pull through this crisis better than past crises".

1997 was the year that Ong faced the first of four major economic crises he found himself in the thick of in his adulthood thus far: the Asian Financial Crisis.

Then, he explained, retrenched workers (especially those in the electronics industry) were in need of new jobs and retraining.

The follow-up from that was a decision to make re-training programmes permanent. Over the years, Ong says, "labour market intervention became a government function".

The "system and infrastructure" for retraining proved to be "very useful in 2008", during the global financial crisis, and is today a system that the government can "leverage heavily".

What this means in practical terms is that, as Ong points out, employers can make use of existing funding schemes instead of having to be briefed about entirely new initiatives.

Training centres, he says, have already been set up with a framework for accreditation, so that workers who go through training are able to obtain certification according to industry-recognised standards.

They can then go on to tap on job placement services.

"Imagine if we didn’t have SkillsFuture, and you're starting from scratch. It would be even more difficult."

"This is the worst. This will be the worst."

The 1997 head start, while significant, is not to be taken for granted, however, given the severity of the present situation.

As Ong cautions, "I'm afraid to say this, but this will be the worst (recession we will go through)."

He recalls how the impact of the previous economic crises had been limited to particular regions (as in the case of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997), or particular sectors (as in the case of the dot com burst in 2001).

However, the current crisis, being global, and affecting almost all sectors, is the worst of both worlds, Ong says.

Advice for fresh grads: "just make sure you keep on learning"

And so Ong has this advice for fresh grads:

- Take up good job offers: "If you have a good job, take it, and start your career", he says, pointing to the fact that in sectors like business, infocomm and technology, as well as engineering and accounting, "some companies actually are still growing".

- Take on a traineeship: MOE is working with companies to get more to offer traineeships, for which, training allowances will be funded by the government. This is an option that helps to ensure that "your learning [doesn't] stop".

- Sign up for postgraduate courses: ITEs, Polytechnics, and universities are launching new courses, Ong shares, which confer either a postgraduate certificate or diploma certificate.

- Do some volunteer work: Finally, Ong says that he hopes recent graduates will look into volunteering, as many in Singapore are in need of help. "Being a graduate, I think you're still in a better position than many of those who are struggling to cope with the impact of the crisis", he says, adding that it can be a platform to learn too, as it is "always a humbling experience to be working on the ground in the community".

True to his post as Education Minister, Ong pithily sums it up as: "various options (of what you can do during this time), just make sure you keep on learning".

Confronting harsh realities: "a bit like losing an election"

Asked about harsh realities fresh graduates will need to face up to, Ong says plainly: "the job market is down".

As a result of this, he says, some may start to compare their options with their juniors' relatively-favourable prospects, and think "how come I am so unlucky?"

Ong quips, "maybe, it is a bit like losing an election".

Ong's electoral defeat in 2011 to the Workers' Party team in Aljunied GRC in his political debut is not something we intended to speak to Ong about, almost 10 years after the fact.

But it's something he candidly — and perhaps even smoothly — acknowledges as a part of his backstory, which he uses to encourage those who are entering the labour market amid a recession.

"When you're at that spot, and you start comparing who’s ahead of me, who's behind me, you start feeling down", he says.

"But if you look at your whole career in perspective, you know you have your whole career ahead of you, it is still up to you to make it what you want it to be, for you to shape.

If you happen to get stuck, and you start to lament ‘why am I behind’, that is the worst thing."

One can only wonder how much of that advice comes from personal experience.

Still, Ong's hope for the current batch of graduates is that they can prove themselves as "the most resilient batch of graduates in recent years".

"You are graduating during our most difficult recession. How you overcome it will be a mark that you can wear with some pride."

Preventing the loss of a generation

On the note of overcoming the current crisis with pride, Ong is quick to credit his ministry for having achieved some measure of success thus far in the fight against Covid-19, in terms of preventing a "lost generation" and in keeping schools safe.

"People do not quite appreciate the long-term, profound impact of losing a school year. That is when you may have a lost generation", he says.

The term "lost generation" was recently used by Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat, describing how global crises had, in the past, created lasting impact on the employability and incomes of youth at a given point in history, such as after the First World War.

There were "two important decisions", Ong says, that helped prevent a "lost generation" of students. These were:

- Implementing Home-Based Learning in April, and

- Moving the mid-year school holidays from June to May

These moves helped to preserve the school year, albeit with some curriculum time being lost, Ong says, and made sure the current cohort does not fall too far behind in their schooling.

"We scrambled", Ong recalls, to ensure that school closures in April would not unduly impact vulnerable students, who suffered the most from the disruption to routine. "I'm glad they're all back in schools now."

Ong shares that one unexpected positive outcome of the whole situation is that some long-term absentees are coming back to school after two months of closure in April and May.

"They actually came back themselves, so now we have to see how we hold on to them", he says, with a laugh.

Keeping schools safe

While there are still seven yet-unlinked cases among students and staff there is no evidence that their infections happened in schools.

And besides, Ong’s focus seems to us to be less on the numbers and more on the mindset everyone has toward overcoming this crisis.

"I think what we have done not too badly is that institutionally in MOE, there is a strong belief that teachers working with parents and students, together, we can keep schools safe. And indeed we have."

This was a course that Ong and his ministry were able to stick to, in the face of criticism, calls to close schools, and even outright fearmongering online, of which, at least one case ventured too far, and was dealt with under the Protection against Online Falsehoods and Manipulations Act (POFMA).

There, the target of that POFMA order was a statement which implied that that infections among staff and students of MOE schools were due to schools not having closed earlier than they did, on April 8.

On one hand, as MOE itself acknowledged, as of April 3, there were indeed 69 students and staff from MOE schools among the confirmed Covid-19 cases in Singapore, facts that possibly led to the perception of schools being unsafe.

Be that as it may, the reality was that all these cases were attributed to transmission via other sources, such as overseas travel and households.

It would seem that a gap between perception and reality was what allowed the statements to gain (at least some) traction, prompting action under POFMA.

Ong seems convinced that the way to bridge gaps like that, at the end of the day, is consistent communication:

"Keep on putting out the information, keep on explaining, and I think over time, the public will likely understand.

I think as it is, many Singaporeans are on the same page."

And Ong will continue to read his emails and personal messages, from his public account, post Facebook Q&As and videos to his teachers and parents, as he strives to inform Singaporeans, one by one.

The Mothership Covid Interviews is a series of conversations where our young writers sit down with key figures in Singapore to talk about the ongoing pandemic, its effects on Singapore’s society, economy and polity, and how the folks we talk to are coping, or helping Singaporeans cope. And in some cases, we talk about fun stuff too.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.