Update on Feb. 26, 8.00pm: One of the Bangladeshi workers from the Seletar Aerospace Heights cluster (Case 56) was discharged from hospital on Feb. 26. He was in the hospital for 13 days.

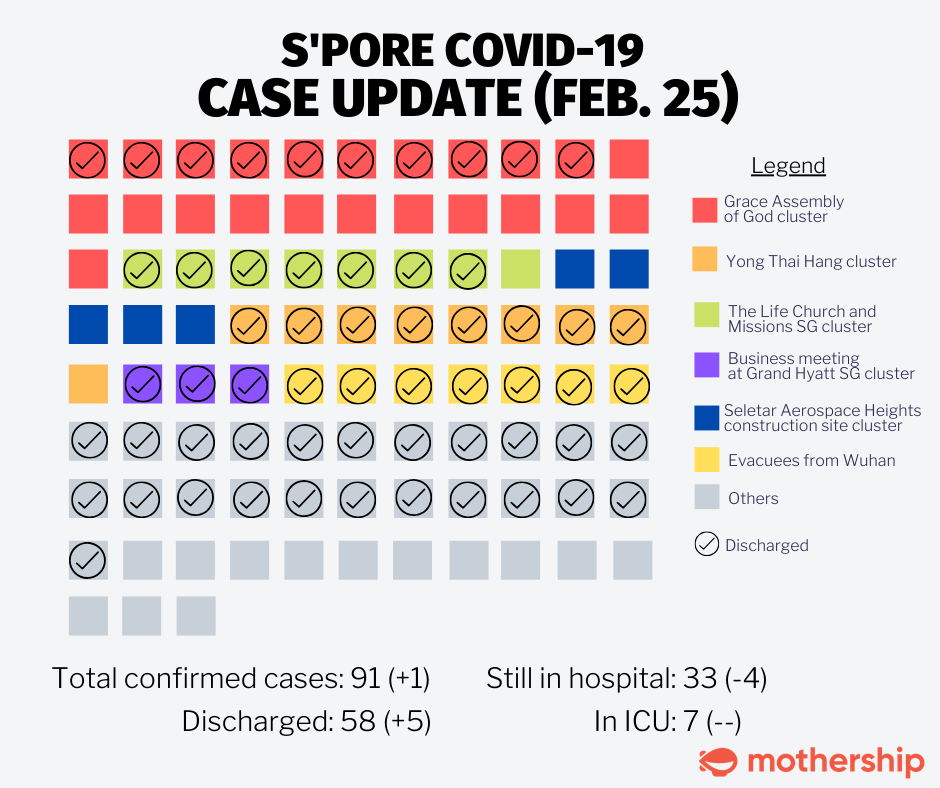

Singapore is making good progress with the Covid-19 outbreak. As of Feb. 25, 58 out of 91 confirmed cases have recovered and been discharged from hospital.

But if you were to examine this infographic a little closer, you might notice that all five cases linked to the Seletar Aerospace Heights cluster are still in the hospital.

Strange, considering that it is the only cluster that doesn't have a single patient who has recovered and is discharged from the hospital yet.

These five patients — Cases 42, 47, 52, 56, and 69 — were diagnosed on Feb. 8, 10, 12, 13, and 15 respectively. All five patients are Bangladeshi workers.

And they have been hospitalised for quite a long time.

The average period from diagnosis to discharge for all 33 Covid-19 patients who are still hospitalised (as of Tuesday, Feb. 25) is around 12 days.

Four of the patients — Cases 42, 47, 52 and 56 — have been hospitalised longer than that. Their stays have ranged from 13 to 18 days, and counting.

Also, aged between 26 and 39, the five Bangladeshis are also significantly younger than the average age of Covid-19 patients in Singapore (43 years).

The gap is even bigger if you compare the Bangladeshis' stays to the others who are still in the hospital. The average age of those who are still hospitalised as of Feb. 25 is 48 years.

We also learned that one of these patients, Case 42, is currently in critical condition because he has underlying respiratory and kidney conditions.

We don't know if any of the other four Bangladeshi patients are in critical condition, bearing in mind that seven of the 33 still in hospital are in the ICU.

Neither can we provide a definitive answer for why this cluster of Covid-19 patients has not recovered, barring patient-specific information from the Ministry of Health.

When contacted, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Health declined to share medical information pertaining to specific cases.

So why are these young men in particular still in the hospital?

People who are young, old, or have a weakened immune system will generally take longer to recover from a virus infection.

We can't be sure (in the absence of more information) but it may be that these migrant workers have weaker immune systems or are generally in poorer health to begin with.

And if we were to take this thought process further, there are a number of possible reasons why this seems to be the case, especially among our thousands of foreign workers doing labour-intensive work in our construction and manufacturing sectors.

Here, we examine two key factors that may play into their predicament:

1. Food that is lacking in sufficient nutrition

Here are four reports we could find on the issue in the past five years:

2015: Shameful state of meals given to foreign workers reveal what this country is built on

2017: Foreign workers in Geylang still made to consume rancid food in 2017

2019: In rich Singapore, why must migrant workers go hungry?

As recently as in 2017, migrant workers were provided meals that were prepared up to 12 hours beforehand.

As a guideline, the National Environment Agency (NEA) advises that ready-to-eat meals should be consumed within four hours from the time they are prepared.

Past examples of rancid food include foul-smelling curry, rock-solid fish with scales still intact, and roti prata so hard that it feels like one is “chewing on plastic”.

If you're thinking that these meals are provided free-of-charge, think again. Catered meals for migrant workers were known to cost as much as a quarter of their monthly salary, a 2015 study found.

Its researchers, who interviewed 60 Bangladeshi workers, found that their meals were sorely lacking in nutrition. The workers also often complained of stomach problems.

The 2019 South China Morning Post report above highlighted a case of a 32-year-old Bangladeshi worker who lost 10kg because he was not eating proper food.

Weight loss and rancid food

Desiree Leong from the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) told Mothership that some workers do appear much thinner (as compared to their passport photos) by the time they approach the voluntary organisation for assistance.

Ethan Guo, General Manager of Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), also told Mothership that migrant workers who come to them always report that their meals are bland and tasteless.

Here are some photos, courtesy of a migrant worker, that he shared with us:

Via TWC2

Via TWC2

Via TWC2

Via TWC2

"As you can see, it's pretty much just rice with whatever that liquid mess is (likely diluted dhal)," said Guo, who also confirmed that sometimes workers get rancid food because it is delivered in the morning and eaten only in the afternoon.

The SCMP report paints a slightly less grim picture.

Workers get up to three pieces of flat bread (like prata or chapati) with a side of dhal or curry for breakfast. Lunch and dinner usually consists of white rice, curry, a portion of meat and vegetables.

However, because the meals are usually delivered early and left sitting for long, they either go bad, or get ravaged by rats or dogs.

One worker told SCMP that he usually throws away half of the rice simply because it is inedible.

And so, faced with hunger, what can migrant workers do? One told SCMP that he depends on caffeine-enhanced energy drinks to fill him and keep him awake.

Taking these drinks over the long run, though, can result in a host of medical complications like high blood pressure and diabetes.

And why is catered food for foreign workers so bad?

Catering industry has very low margins

The problem lies in how the cooking is outsourced to cheap caterers with low profit margins, says Guo.

According to an industry player who spoke to SCMP, caterers make about US$0.30 (S$0.42) per meal.

A caterer that SCMP spoke to said his company supplies workers with three meals a day at the cost of US$105 (S$147) per month. This works out to be about US$1.20 (S$1.70) per meal.

The low price of the meal reflects its shocking lack of nutrition.

Caterers are willing to slash prices — and in the process, compromise on ingredients, nutrition, and quality — because migrant workers' demand for food is extremely price sensitive.

Paying less for food means having more money to send back home.

Which begs the question:

Is malnutrition a prevalent issue among migrant workers?

According to Leong, malnutrition is not a common complaint among workers who approach HOME.

"We do not see usually see workers come to us specifically, primarily or even substantially for complaints about food issues or malnutrition. Even when the workers mention poor quality of food or complain about inadequate/no food provided, the effect that this has had on their health is not medically investigated, much less established."

Even when they do approach HOME with issues of dietary deficiencies, she said, it is usually alongside more pressing issues like unpaid salaries and workplace injuries.

"As such, we do not have data to comment on whether malnutrition is prevalent among migrant workers in Singapore."

Of course, not all migrant workers are subjected to S$1.70 catered meals.

Some of the larger dormitories are equipped with kitchens and grocery stores which make it easier for workers to cook their own meals — often in groups — giving them much more control over how much nutrition they get.

And so, some venture to Little India on the weekends to stock up on groceries, cook their own meals and bring them to work.

This means that some migrant workers have some form of agency when it comes to their food, and can be responsible for their own nutrition.

But this brings us to an underlying issue: low wages

So is malnutrition really an issue for migrant workers? If it isn't, why do we need NGOs to "step in" to provide better food for them?

The underlying problem, said Leong, is "extremely low wages".

Because their wages are so low, basic living expenses take up a large proportion of their income. Two things will happen, she said:

"First, they are pressured to scrimp and save on their living expenses so they can remit more money home, even to the point of opting for the cheapest, worst food.

Second, they are pressured to work very long hours to earn more. The strenuous work exacerbates the nutritional deficiencies; and also leaves them no time or energy to cook, which forces them to accept catering."

How low can migrant workers' wages get? Between S$560 and S$700 a month.

Assuming they work 10-hour shifts, five days a week, migrant workers earn between S$2.69 and S$3.63 per hour (guess a S$1.70 meal doesn't look too bad now).

Guo agrees, adding that employers of migrant workers are also concerned about their profit margins because construction work contracts are usually awarded to the lowest bidder.

"This then has ramifications down the line on issues such as the low salaries, short-payment or non-payment of salaries, lack of adherence to workplace safety and poor quality of food."

Tackling the issue of poor nutrition then requires an overhaul of the way the entire construction sector is structured, he said.

This might take the form of a minimum wage or progressive wage model that ensures migrant workers a salary that is proportionate to living expenses, said Leong.

Which brings us to the second possible reason for their current circumstances:

2) Long working hours, insufficient rest

Poor nutrition aside, migrant workers are also known to work long hours just to supplement their meagre income.

12-hour shifts with one to two days of rest per month are not uncommon among migrant workers in Singapore, according to this Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy publication.

A 2017 TWC2 study that polled over 600 construction workers found that 68 per cent of foreign construction workers work so much overtime that their total monthly overtime hours breached the legal maximum of 72 overtime hours a month.

Migrant workers were also known to have complained about sub-standard hygiene in their dormitories. Issues like bedbugs and poor ventilation lead to sleepless nights. As a result, affected migrant workers get insufficient rest.

The TWC2 report also found that construction workers were getting seven hours of sleep on average. This is the lower end of the recommended seven to nine hours of daily rest for adults.

Being overworked, having insufficient rest, and having little nutrition will inevitably cause one's health to suffer leading to a compromised immune system.

Could poor nutrition, long working hours, and/or insufficient sleep be among the reasons that it's taken so long for the Bangladeshi patients linked to the Seletar Aerospace cluster to recover?

We'll be the first to say that we can't be sure, particularly in the absence of reliable information about their current medical conditions.

We contacted Yi-Ke Innovations Pte Ltd, the employer of Case 42, to find out the types of food and work arrangement the company has with its workers and left a message. Unfortunately, we did not receive a response from them.

Whatever the reasons eventually are for the vulnerable situation these workers are currently in, though, the aforementioned issues remain, worthy of consideration on our part as a society, in terms of how we can render their circumstances less stressful on their overall health.

Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates on Covid-19: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Mothership Explains is a series where we dig deep into the important, interesting, and confusing going-ons in our world and try to, well, explain them.

This series aims to provide in-depth, easy-to-understand explanations to keep our readers up to date on not just what is going on in the world, but also the "why's".

Top image via Google Street View.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.