Portrait Mode is a photo essay series about Singapore and all the people and things in it, seen through the lenses of our young photographers at Mothership.

This week, in celebration of Nurses' Day, we meet eight different nurses who work at a range of hospitals in Singapore in a range of different roles. We ask them about their challenges, their joys, and their inspirations.

Pregnant with third child & working the high-dependency night shift

At 8am, most people still have a whole day of work ahead of them.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Nur Salina Binti Abdul Kadin, however, is approaching the end of her shift that started at 9pm the night before.

The 33-year-old is a staff nurse at Mount Elizabeth Hospital, working in the High Dependency Unit.

She tells Mothership that the unique nature of the ward requires her to perform resuscitations on patients fairly often.

"We have patients that always come back (into the unit). We call them our regular customers. There was once a patient's (condition deteriorated) and we had to resuscitate him and we sent him to ICU (Intensive Care Unit). The patient's relative came back and said 'Wow, I'm so proud of you [laughs]. You did a good job and you saved his life.'"

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Describing herself as someone who enjoys the challenges that come with being station in the High Dependency Unit, Salina is also currently taking on a different challenge — working while pregnant.

"You get morning sickness. Then you feel nauseous. Sometimes you have no appetite but you still need to work.

I think I just want to experience it. During my last pregnancy, when I had twins, I was not working. I want to try how's the feeling of working during my pregnancy."

Working with dementia patients, and going back to school twice

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

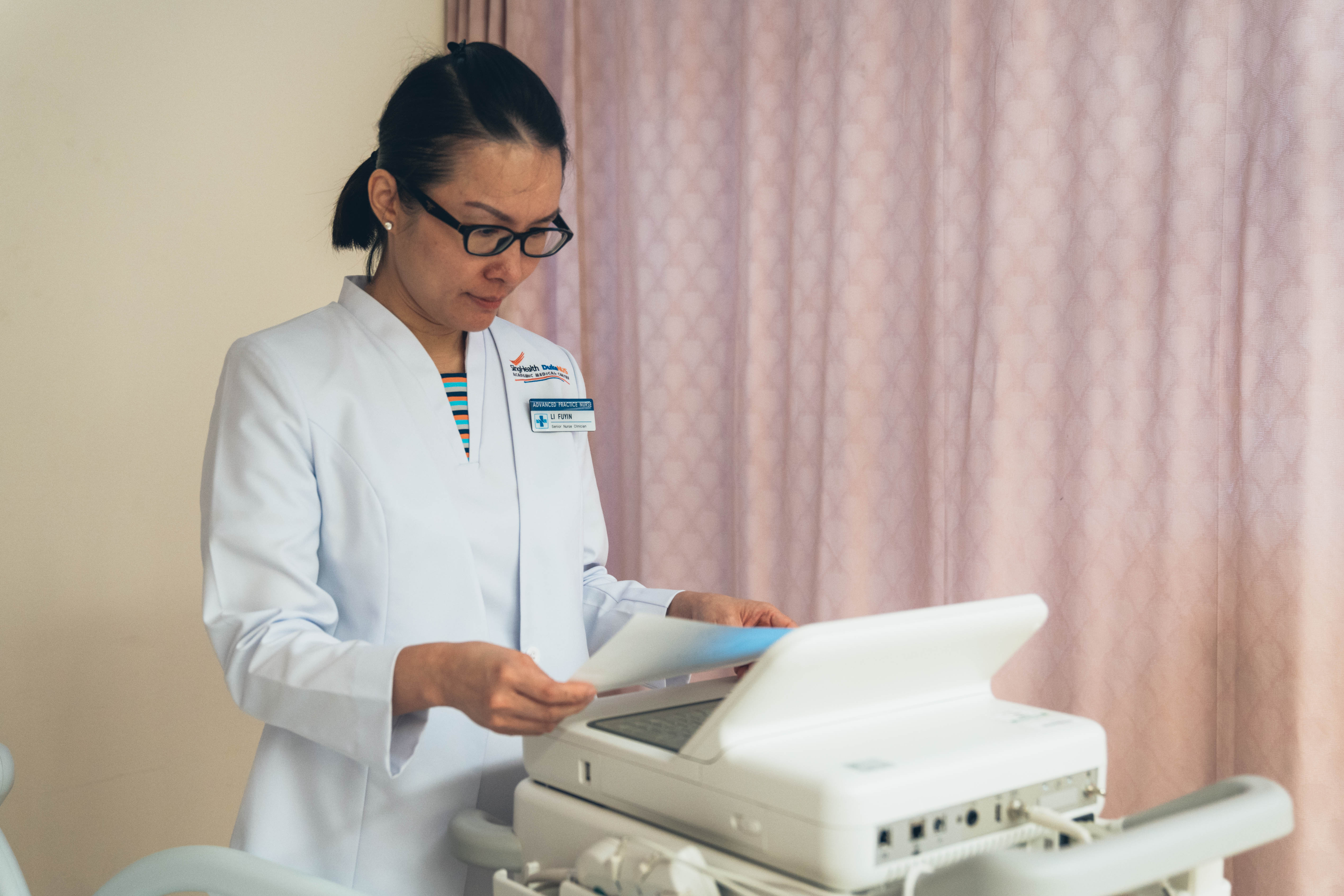

Another nurse who doesn't shy away from challenges is Li Fuyin.

As an Advanced Practice Nurse in Changi General Hospital's (CGH) geriatric ward, Li, 40, works specifically with patients suffering from dementia.

Her love for her work started as she was doing the rounds in regular wards, where she often encountered elderly patients with dementia.

"Part of the complication for dementia that may develop subsequently may be behaviour problems. And a behaviour problem can be quite challenging for the caregivers to deal with at home, as well as for the formal caregiver, like the nurses.

And from there I saw an interest and a need to go deeper — a deep dive into developing better care for patients with dementia."

The interest drove Li to return to school twice — first for an advanced diploma in gerontology (the scientific study of the process of ageing), and then a Master's in nursing.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

One of the most satisfying experiences of Li's 17-year career was when she formed a close working relationship with the son of a patient who was diagnosed with dementia:

"The son loved him a lot and therefore there was a lot of pressure and stress on the son. Every single time the son came in [to visit his father in the hospital], he would express his level of stress from caring for the father... Interestingly, the son felt relieved whenever he came into the hospital and when we taught him how to manage his father's behaviour. He would say, 'I would never have learnt this if I did not come and have caregiver training with you.'

Every few months when he comes back to bring his father for physio(therapy) or to see a doctor for a follow-up appointment, he will automatically drop by our ward and give us an update on how his father is doing at home. That is really great. We love to see that kind of collaboration."

Improving life for both patients & nurses with tech

For some nurses, work entails more than just caring for patients (if we can even use "just" to describe this weighty task).

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

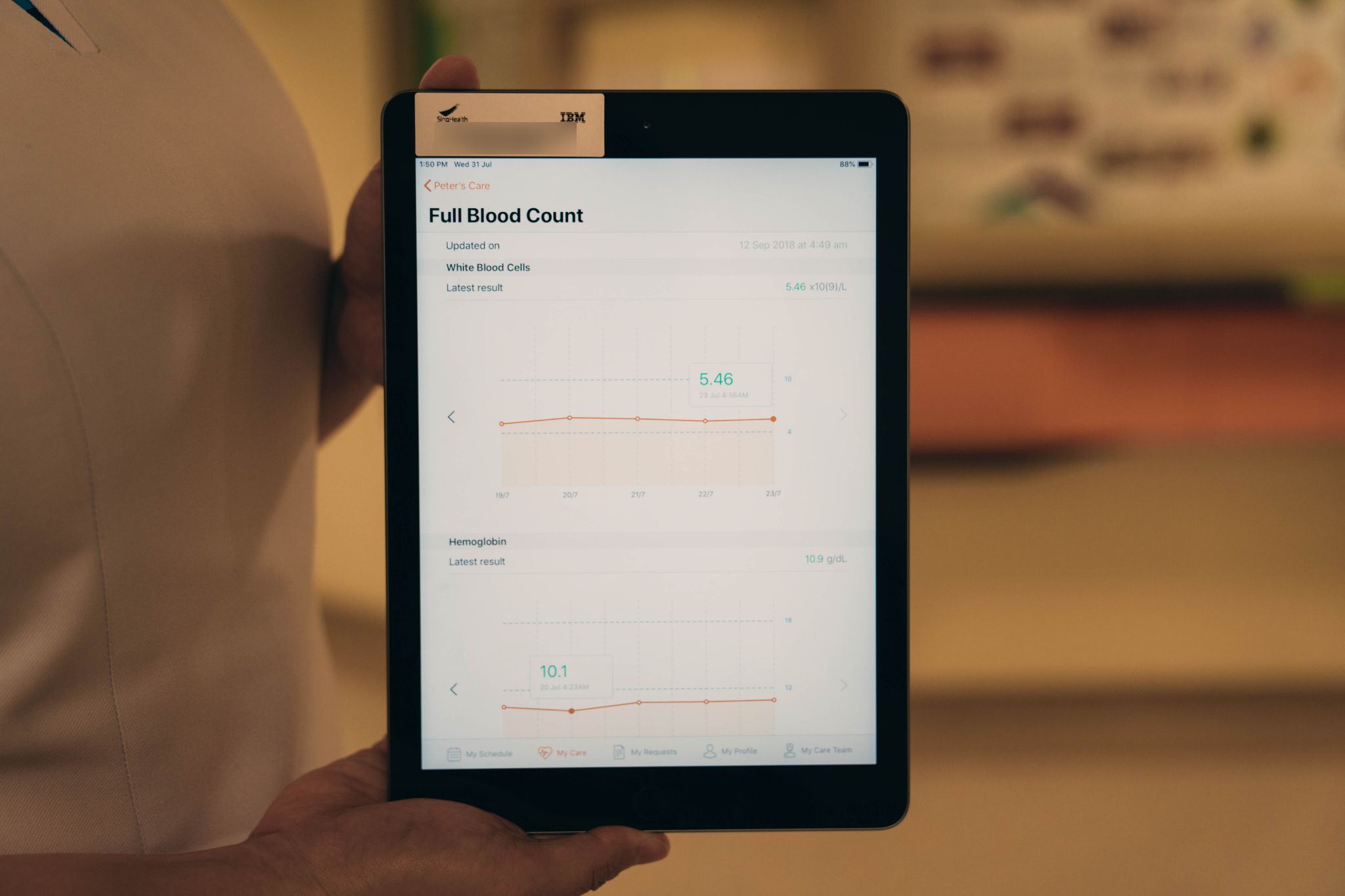

One example is Tan Sheng Lian, an assistant nurse clinician at Singapore General Hospital's (SGH) haematology department.

The 30-year-old is also involved with the hospital's research and transformation projects.

"When Ms Ang (Ang Shin Yuh, deputy director of nursing quality research and transformation at SGH) initially asked me, 'Would you like to work with me on a bedside tablet project' — this is just an inside joke — being a nurse right... I didn't think of (an electronic) tablet, I thought of medications. So I was like, 'Oh you mean the patient's own medications?' But in the end, she told me 'no, tablet as in iPads.' Then I'm like 'Oops!' So embarrassing!"

Initial confusion aside, though, Tan says the project has proved immensely rewarding.

She explains how the tablets are loaded with an application that allows patients to get updates on their latest tests results as well as information on their conditions.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

It also has a function that allows patients to request drinks or extra blankets, for instance.

These advancements in technology empower SGH's patients, and give the hospital's nurse more time to do actual nursing.

"Actually now (the patients) are more appreciative of it. Initially some of them have some doubts about it, like you know, 'you are replacing the nurses with a tablet so I'm not going to see my nurse in charge anymore.' Now actually, no, because the tablet actually frees up more of our time. Like I said, it improves our efficiency and productivity. So from there we actually get to spend more time talking to the patients."

Teaching nurses how to do their jobs well

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Arthi Devi, too, may not quite fit the mould of a stereotypical nurse.

Instead of a ward, she paces up and down the aisles of a lecture theatre as a nurse educator at Gleneagles Hospital.

Amongst the skills she teaches, Arthi is especially passionate about imparting the significance of good communication to the next generation of nurses.

"Keeping a family updated is very important. Not just the family but patients as well. Patients come in and it must be made known what is happening to them. If not, they are already sick, right? So we don't want them to come in with the worry that 'no one is telling me anything about myself, so I won't know what is happening.'

I feel that it's not fair for patients to come in feeling that 'I'm already ill, I have to be taken care of, but I'm not being told what I have or what's next for me.'"

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

The 36-year-old former ICU nurse says she does miss being in the thick of things, but teaching can be very rewarding — with one experience, in particular, taking the cake:

"When I was delivering (my baby), one of the nurses came to me and said 'You were my lecturer once.' I looked at her and said 'Okay, I'm so sorry I can't remember at this stage.'

(During the delivery) she kept on explaining to me what was happening and it was very nice to see her. I thanked her... and she said 'Actually this is what you have taught me!'"

Facing blood & traumatic amputations

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

In her work as an advanced practice nurse specialising in trauma at CGH's surgical ICU, Serena Koh is often exposed to sights most of us can't handle.

"You must have a very bold heart (to be a trauma nurse) because I see blood on a very regular basis or broken bones. You need to be bold. And on top of that, you must stay calm.

I have patients that have traffic accidents or industrial accidents where they fell from heights. I have patients who have been assaulted and patients who have sports injuries."

The 42-year-old's most graphic case was a patient who suffered from the traumatic amputation of both his lower legs.

"It's been years but I still recall it," she says.

"Initially yes, I found it a bit graphic. But if you don't put up with these kinds of graphic scenes you can't help the patient, so that's (what gets me through it) — wanting the patient to be treated as early as possible kind of takes away the (fear or shock from blood and amputations)."

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Having worked for 21 years in this demanding career, Koh says her Christian faith and her family have helped her persevere in tough times.

"My spouse is also a nurse. But he's an occupational nurse; he's not in a hospital. So he actually understands the commitment I have. So I guess with the support from him I can do what I want to do — working late."

Tending to patients from overseas who are weak or at the brink of death

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

For Cheryl Lin, an assistant nurse clinician at Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, strength to endure stressful times is also drawn from others.

Working in the medical and surgical ward of a hospital that treats lots of patients from overseas has meant that Lin often finds herself having to navigate culturally complex situations.

"We just have to be more aware of the cultural differences, because for some patients for instance, when it comes to hygiene they can be different from (what) Singaporeans (are used to). So probably, they just don't like to shower for instance and we can't push it so much onto them.

And you know, you'll be in this difficult situation where you're trying to address and meet their hygiene needs and they just don't want it, because in their culture they just don't do it at all. It's interesting, but it can also be challenging. It gives me insights, to actually understand their culture a bit more."

The other challenge, Lin says, is that the nurses see many patients who are often in a weak state and at risk of dying.

Constant exposure to such suffering can take a huge emotional toll on the nurses.

Thankfully, the 33-year-old says, she has a great team around her to lean on for support.

"The teamwork in this ward I would say is very good. All the colleagues in this ward work really good with each other.

We are really close in this ward, the nurses. So we will usually sit down, perhaps when a patient has passed on, we will sit down to talk things out. Let's say if one of staff is really very affected by it, we will just get bring them out and just talk over dinner and lunch to help them move on from there."

Bringing nursing care to patients' homes

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Sri Ratina Wati Binte Abdul Razak, 33, is a senior staff nurse who doesn't work in a hospital.

Instead, she is a community nurse, serving various neighbourhoods in the Bukit Merah area.

Her work sees her in constant contact with the elderly, many of whom live in one-room flats and by themselves.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

But working in the homes of her patients has meant that Ratina (or Tina, as she is affectionately called) often finds herself building quite a close bond with them.

"I'm always very attached to my patients. My patients are like my own family. Getting attached to them, in way is good and bad because I know how to better manage them, like emotionally. Sometimes I will know what is the real cause of non-compliance (to treatment). Or I would know (how to get through to them). I can just text the family members.

I try to engage the family as a whole because I know health isn't just about the elderly. Yes, you have to ensure that the elderly know how to manage themselves. But in reality you have to engage everybody in the community."

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

And so, seeing her patients thrive gives Ratina an additional sense of purpose.

"For example, I have a dementia patient who I have been constantly reminding every day to take his medication. And he keeps forgetting, right? So finally when he remembers after three months of reminders, that's the satisfaction that I get.

I mean if you want to look for rewards, and I'm not looking for rewards here. But I'm looking for the satisfaction."

Seeing cancer patients on their entire journeys

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Ratina's experience mirrors that of Pierre Yim, an oncology nurse at the National Univerity Hospital (NUH).

"As an oncology nurse, I think we spend a lot of time with our patients in that we really see them along their entire journey. Like from the time they are diagnosed, to when they are undergoing treatment, or when they have complications. Even at the end of their life, the oncology nurses are always there at every stage. We know them so well.

It's this deep involvement (in the lives of patients) that really attracted me (to the job). It's like you not only get to learn about the disease, you not only get to learn about the treatment but you also get to learn about the person."

He tells me of one particular patient that has summed up his five years working as a nurse thus far.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

The elderly man had gone through various treatments and stints in ICU at NUH, and Yim and his colleagues had taken care of him over the course of five months.

"At the end, he was already very weak. And everybody was just trying our best to keep him alive. I don't think there was much quality of life left because honestly, he spent all of his time in hospital. He was quite upset, and he looked like he had pretty much given up already.

One of the last few things the nurses did in the ward was we just tried to engage him every day, tried to talk to him every day. We did the little things for him — brushed his teeth, wiped his face, applied moisturisers. We tried our best to shift him out of bed, to let him sit up in a chair so that he feels a little bit more normal instead of just lying in a bed all day.

I think towards the end these things really brought a smile to his face... I think he was happy in these moments."

Yim says the story, in his own words, is not very "bombastic" but to him, it perfectly illustrates what nursing is all about.

"I think nursing is a lot about what we do with our hands, what we say with our mouths. But above all, as nurses, we also make this connection with our heart, with our spirit. We connect with the patients spiritually, and I think this is a really beautiful thing."

Top photos by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.