Samuel Wong and Yang Ji Wei — founders of the TENG Ensemble — are very passionate about Chinese instruments.

As Yang, 38, gives me a short demo on the sheng, he shares very excitedly that the instrument is very special because it can play multiple notes together in a chord, unlike other wind instruments.

Yang Ji Wei and his sheng. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

Yang Ji Wei and his sheng. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

As he blows into the sheng, I watch as his throat expands and contracts rapidly, his fingers dancing across its bottom, emitting a cascading wave of notes.

That, he says, is a technique called the hu she, which brings to mind a phoenix spreading its wings.

"Fat people play sheng," he says with slight self-deprecation, "because the conductor will assume you have a lot of air."

Wong, on the other hand, was allocated the pi pa when he was young because of his small fingers.

"Small fingers means agile, you see," grins the 36-year-old.

Samuel Wong on his pi pa. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

Samuel Wong on his pi pa. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

Agility, as it turns out, is very important for a pi pa player who needs to make every finger pass the strings at the same speed and with the same strength — which is not normally possible, he explains, because of the way our fingers and nerves are designed.

"The pi pa is a lot more violent as an instrument," says Wong while giving it a series of hard, successive strums. "So it's always used to talk about war."

Formed in 2004, the homegrown TENG Ensemble has been playing fusion songs using Chinese instruments for over a decade.

Chances are you might have come across their viral Disney medley, or even their 2016 fusion album "Stories from an Island City":

Aside from Wong and Yang, the ensemble consists of Darrel Xin (er hu), Gerald Teo (cello, ge hu), Joachim Theodore Lim (percussion), Johnny Chia (gu zheng), Neil Chua (da ruan), Eugene Seow (bass, percussion), Jeremy Wong (pi pa), Joel Chua (keyboard, electronics), Leonard Goh (guitar), and Phua Ee Kia (countertenor).

Made fun of as Chinese Orchestra players in the most un-Chinese school

So perhaps it is rather fitting (or ironic) that Wong and Yang's interest in Chinese orchestral music was first piqued in pretty much the most un-Chinese place — the Anglo-Chinese School (ACS).

Being a Chinese orchestral player in ACS subjected Wong and Yang to a lot of ridicule from their schoolmates (and sometimes even their families) for playing a lot of "cheena" things.

They tell me people would ask, for example, if they were going to play at funerals when they grew up.

But it was at ACS that both had their first taste of fusion music — playing Christian hymns with Chinese instruments.

The ACS Chinese Orchestra was one of the first Chinese orchestras in Singapore to play hymns. As a group operating in a Christian school, the orchestra was called up to play hymns during chapel sessions.

Interestingly, the students at chapel took quite well to the arrangement and sang along, according to Wong.

"You can say that back then we already realised that Chinese instruments can do different things, not just traditional work," quips Yang.

These experiences additionally stoked Yang's and Wong's interest in the instruments, and so they tell me they took up lessons privately and joined external orchestras (such as the Singapore Youth Orchestra) to build up their playing techniques.

Yang and Wong. By Ng Kah Hwee.

Yang and Wong. By Ng Kah Hwee.

Yang shares that when he was training under his sheng teacher, Guo Chang Suo (currently the sheng principal at the Singapore Chinese Orchestra), a typical training day stretched over seven to eight hours at Guo's house.

"Back in those days, I think the agenda wasn't about teaching. It was more of grooming someone. To the teachers, they really treasured the opportunity to teach a very serious student."

Gruelling schedules trained Wong and Yang to be the fine musicians they are today.

Wong, who has a PhD in Ethnomusicology from the University of Sheffield, is currently adjunct faculty at the University at Buffalo-Singapore Institute of Management (UB-SIM) and a Dissertation Supervisor at LASALLE College of the Arts.

Yang, a three-time national sheng-playing champion at the annual National Chinese Music Competition, has conducted various schools' orchestras and founded the first sheng ensemble in Southeast Asia.

Breaking stereotypes of Chinese music

Having both won individual championship titles at the National Chinese Music Competition, both Yang and Wong could no longer compete as individuals.

So to get around that, they grabbed a few other soloists and formed the TENG Ensemble in 2004 to return to the competition — which they also won, of course.

The name TENG comes from the Chinese character "鼟". It is used to describe the sound of a drum.

"Its main purpose at that time was to break stereotypes and create projects that were going to blend the East and the West... instead of being a traditional Chinese ensemble," says Wong.

For both Yang and Wong, the ensemble is an opportunity to reinvent Chinese music.

And that did make us think about the fact that people don't see the piano as a "Western" instrument, because it is used in both English and Mandarin pieces.

For Yang, the sheng is not just an instrument for Chinese music. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

For Yang, the sheng is not just an instrument for Chinese music. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

But when it comes to the pi pa or sheng, it's hard to see it as anything else than a medium for Chinese pieces.

To this, Wong predicts this stereotype will change when the world is exposed to more fusion music, like the TENG Ensemble's repertoire.

Says Yang:

"We don't really see them as 'Chinese' instruments. We use them to express our emotions. That's what sets us apart from a Chinese musician from China, a Chinese musician from Hong Kong, or a Chinese musician from Taiwan."

Lifting the underprivileged

Beyond their music outreach, Yang and Wong also use Chinese music to lift up the underprivileged.

After winning the National Chinese Music Competition in 2004, some members of the TENG Ensemble formed the TENG Company to create and develop projects related to Chinese instrumental music.

These projects aren't all related to pure performances. Yang shares that the non-profit arts company (it is funded through sponsorships, grants, and fundraising events) is committed to Chinese music research, education, and community outreach through their music.

For example, the TENG Company has been working with the Association of People with Special Needs to run specialised classes for people with special needs since 2018.

These classes equip people with special needs — many of whom are on the autism spectrum — with basic music skills and the opportunity to work with others. In the process, they open up and gain self confidence.

For Wong, TENG's mandate is to help the underprivileged through Chinese music. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

For Wong, TENG's mandate is to help the underprivileged through Chinese music. Image by Ng Kah Hwee.

In March, the TENG Company put up a concert for these special needs students to perform using their newfound skills.

Yang shares:

"You know the joy you see in these special needs performers when they're given the opportunity to be on stage — even if it's just for five minutes — in front of a seated audience, on a proper stage with proper lighting, and the applause that comes, it brings about positive changes and that's empowerment.

They were so happy when they came backstage, they high-fived us!"

The TENG Company also helps underprivileged students through the Direct School Admission scheme.

"We sensed that the market has this inequality because only talented students with access to music can go to better secondary schools," says Wong.

They created the Mapletree-TENG Academy Scholarship for underprivileged students that started last year as well, under which members of their band mentor them in playing Chinese instruments and equip them with musical skills.

Now, the Mapletree-TENG Academy platform gives out scholarships to four students each year. So far, one of their scholars has applied successfully to a polytechnic through the DSA using the skills he learned from them.

Bringing Chinese musical instruments to the masses

The Teng Company's Chinese music outreach extends beyond programmes.

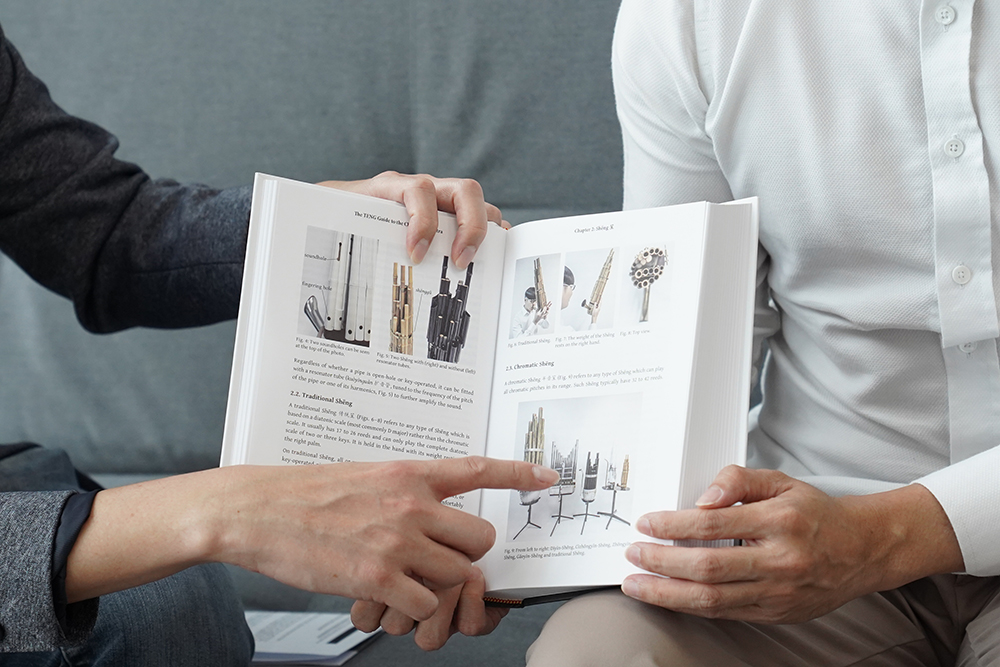

It recently launched its very own book, The TENG Guide to the Chinese Orchestra — a comprehensive tome for composers, musicians, and even the average music enthusiast to learn about and write music for Chinese instruments.

The TENG Guide to the Chinese Orchestra. Image by Ng Kar Hwee.

The TENG Guide to the Chinese Orchestra. Image by Ng Kar Hwee.

While it is intended to help composers and musicians work with Chinese instruments, it's also written to be accessible enough to the average Joe on the street interested to learn about Chinese music.

The TENG Guide to the Chinese Orchestra, Wong and Yang say, is just one of the many ways that the TENG Company is investing into keeping music tradition and heritage alive in Singapore.

They're currently working on their latest project — a documentary concert called "The Forefathers Project", which in Wong's words will "reinvent the sounds of our forefathers".

Wong shares that he has been visiting various clan associations and music groups over the past four years to learn about the music from the pioneer musicians of different dialect groups.

"A lot of these forefathers of Chinese music learned their music through the oral tradition. They sang their songs without writing notations. You try to remember as much of it as possible and then you try to do it."

They plan to work on reinventions of Cantonese, Teochew and Hakka music, presented in the Ensemble's signature fusion style, in the hopes that a younger generation of Singaporeans can learn and discover, through music, how our pioneers' style evolved through the years.

The Forefathers Project will be presented as a live performance/documentary screening on October 11, 2019.

The guys cannot share anything more about it at the moment, but judging from Wong's excitement, it's going to be mind-blowing.

If you would like to purchase a copy of The TENG Guide to the Chinese Orchestra, you can do so here.

Top images by Ng Kah Hwee.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.