Portrait Mode is a new photo essay series on Singapore and all the people and things in it, seen through the lenses of our young photographers at Mothership.

This week, we meet a veteran karang guni man who has been in the trade for 27 years. Now aged 55, he owns a warehouse in an Ang Mo Kio industrial park where he gathers with other karang guni friends to sell and recycle used goods.

He spoke to us in a mix of Mandarin and Hokkien, which we attempt to translate in a manner that adheres closely to how he sounded.

This is his story:

Ho Yeong Yan is one of the most realistic men we've ever met.

His almost-lifelong career is one of Singapore's dying trades — karang guni. And he's not shy to admit it, either.

“Nothing much (to like), lah. The money easy to earn, can already. Because nobody bosses you around in this industry. Your mood good, work a bit more. Your mood bad, go home sleep. No one is there to yell at you and say, 'eh this task is not done well'.

But hor, money was easier to earn last time. Now, money is harder to earn.”

Ho, at the coffee shop opposite his warehouse. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho, at the coffee shop opposite his warehouse. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

The rag-and-bone men — or as most fondly know as the karang guni (literally, "gunny sack" in Malay) men, have been around and in business for decades.

They walk through HDB estates honking old-school rubber and metal horns, shouting for used newspapers, old clothes, radios, televisions, and go door-to-door to residents to collect them.

The karang guni men pay a nominal fee for these goods, which can range from as little as S$2 to as much as S$50.

These are then sent and sold to a warehouse like Ho's, and there, they are recycled or reused.

His warehouse in Ang Mo Kio is frequented by no less than 30 karang guni men, who drop off their loot for Ho to take care of.

There are about 10 warehouses like this in Singapore, according to Ho, who started plying the trade in the 1980s.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

Photo by Rachel Ng.

How does one become a karang guni man?

Ho tells us that he started off working at his neighbourhood market when he was 16.

Two years later, he enlisted in National Service (NS). After that, he worked in the renovation industry and helped his uncle at the market selling noodles part-time.

He went on to work with his uncle full-time, but soon stopped because he started collecting newspapers instead, at the introduction of his younger brother’s friend — thus beginning his karang guni journey.

“My younger brother would go upstairs to collect (the newspapers and cardboards). And because he didn’t know how to drive, he asked me to help him and drive him around. My work at the market ended around 1pm. So I’d go home, take a shower, then go out and collect cardboards again.”

I did this for around two years, and then I stopped working at the market. I would start in the morning around 10am, and collect until 6pm. When I didn’t go to the market, my uncle would scold me. Scold until I cannot take it. So I didn’t want to work there anymore, because my uncle was very good at scolding people.”

So I became a karang guni. And I’ve been doing it until now.”

The difference between karang guni and cardboard/newspaper collectors

Except he has, as it turns out, retired from karang guni work. He, and his karang guni friends, kind of see himself/him as the "head" of the karang gunis.

"The people who collect, they are called karang guni. Then here, the warehouse ah, is called 'bong kar' in Hokkien. In Chinese, 'bong' is 'bang' (棒, which means bamboo), 'kar' is 'jiao' (脚, which means leg), so 'bong kar' just means 'bang jiao' (棒脚). It's like, if you (the karang guni) sell us things, we are the 'bong kar'. You all don't know one lah, only the people in our industry will use the term 'bong kar'.'Bong kar' is like the head karang guni lor.

Some people, like the old people, who just collect and pick cardboard and newspapers are not considered karang guni. They're not buying from people. If you are buying from people, then is karang guni lor. Got money involved is then called karang guni."

Ho driving his forklift. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho driving his forklift. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho's friend, Goh Joi Kim, loading newspapers onto the forklift. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho's friend, Goh Joi Kim, loading newspapers onto the forklift. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

The menace of collecting faulty electronics

Old DVD players at Ho's warehouse. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Old DVD players at Ho's warehouse. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

In this new age of social media and the internet, it has been increasingly difficult for trades like the karang guni to sustain themselves. Ho's warehouse is packed with electronics that were frequently used in the early 2000s, but not so much anymore.

"Nowadays, electrical appliances are harder to sell because there are a lot of spoilt ones. Last time when karang guni receive appliances, they will smile. Now they receive, they won’t smile already.

Now they buy for S$20, only can sell for S$5. They lose S$15 leh.

You go buy TV, auntie say she buy for S$1000+. But then, she sell you S$10. Karang guni say, buy S$10 already, maybe need to throw away cos a lot (of TVs) now all spoilt.”

We buy already, then see a lot of lines, means spoilt already. Last time, TVs are more valuable. Now, no more already lah."

Newspapers at Ho's shop. (Photo by Rachel Ng.)

Newspapers at Ho's shop. (Photo by Rachel Ng.)

Being in this line has also given him a strikingly accurate take on the media landscape and how it's evolved here too, an astute observation he brings up while discussing the declining numbers of karang guni men in Singapore:

"It's slowly getting lesser lah. Two more years, will be even lesser. Newspaper getting lesser and lesser lah. Last time, around six years ago, is about 20 tonnes leh. Now it's like five to 10 tonnes only.

Like those deliver newspaper one, go HDB flats, about 100 units, last time can deliver about 90 copies. Now 10 over copies also cannot; no one order newspaper anymore. Now phone can see news already, no need newspaper.

Getting lesser and lesser already ah. This industry will have lesser and lesser (people) too."

The most challenging thing about this job for Ho is also quite surprising to us:

“When the weather is hot, really cannot take it. Collect already, but can’t earn anything. You will go like 'Aiya!!! Weather so hot ah!!! Then cannot earn money ah!!' Then the 'fire' inside you is big.”

It's not something he's passionate about

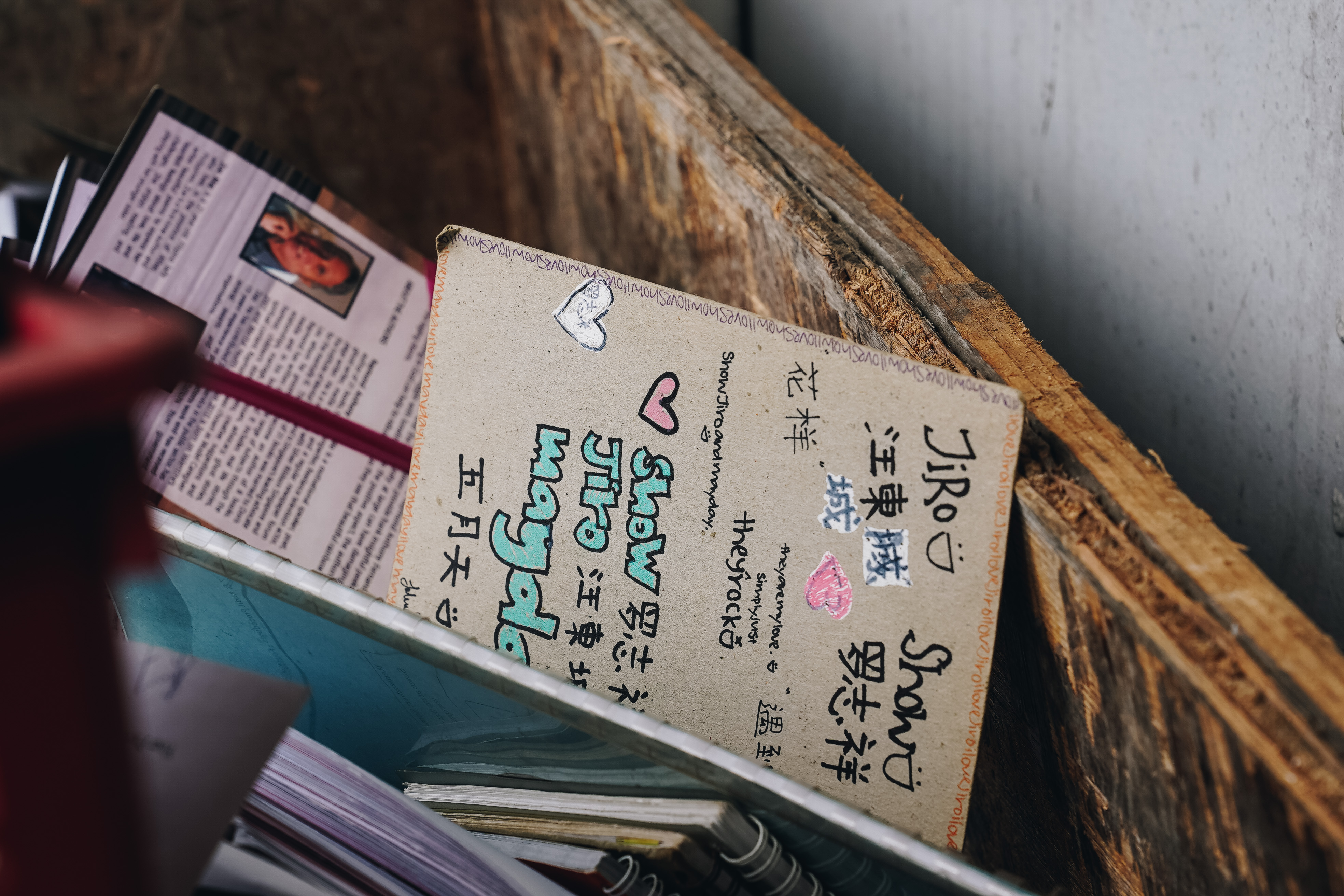

Found in Ho's warehouse: Someone was pretty obsessed with Taiwanese boyband Fahrenheit back then. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Found in Ho's warehouse: Someone was pretty obsessed with Taiwanese boyband Fahrenheit back then. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho makes it clear that this job is not something he does out of passion. He does it to feed his family, to survive, and to earn money. There is no room for romanticism, but he is confident and not even vaguely embarrassed to have been a karang guni man.

"What is there to be paiseh about? We also never rob people, never steal. Any job is also okay lah. Can make money can already, mah. I tell you la, those that opened pawn shops ah, used to start out from karang guni one lah.

Also long as you put in the effort, you put in hard work, and you do work, will succeed one. Don't anyhow spend, don't gamble."

Ho (right), and his long-time friend Ah Hua. "I know him 30 plus years only la, not long," says Ah Hua. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Ho (right), and his long-time friend Ah Hua. "I know him 30 plus years only la, not long," says Ah Hua. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Goh (left) and Ho (right). He insisted we take this photo. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Goh (left) and Ho (right). He insisted we take this photo. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Striking a deal. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Striking a deal. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

You'd think for an island as small as Singapore, and an industry as small as theirs, the karang gunis would have "famous" karang guni men whom they all know and recognise within their circles.

"Everyone also famous lah. I not famous, is my kid make me famous."

(Backstory: we first learned about Ho through a documentary film his son Jackson made about him under the auspices of Honour Singapore, a local nonprofit. He was in his final year at Temasek Polytechnic, and was supported by his classmates and lecturers. You can see it at the end of this story.)

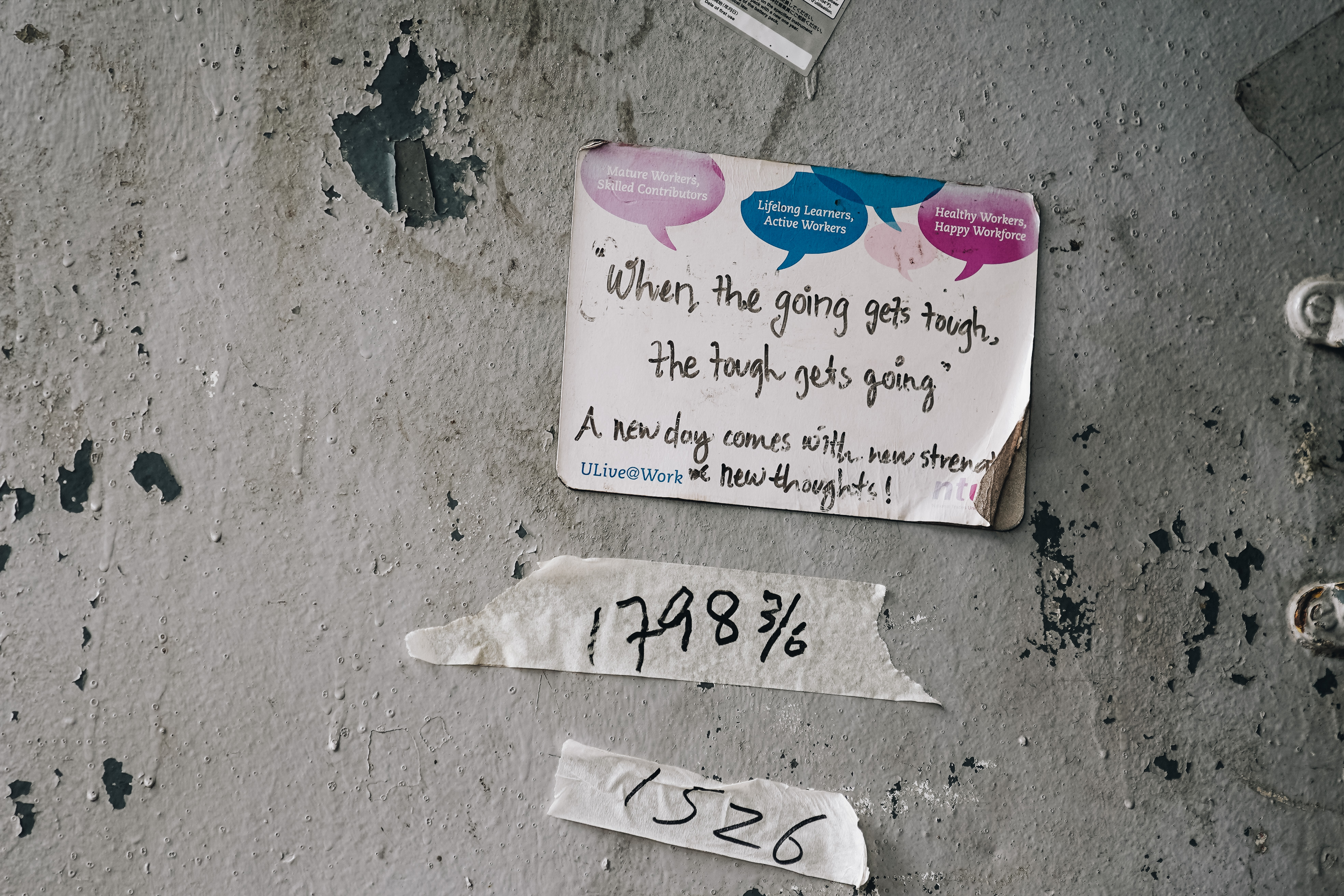

Stuck at the front of the warehouse. Wholesome. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Stuck at the front of the warehouse. Wholesome. (Photo by Rachel Ng)

Might there be a day where Singapore no longer has a single karang guni man?

"Won't one lah. Because now they got people collecting and recycling, the trend is recycling now mah. But for people like us, bong kar ah, I think won't have many in the future. Or if they collect everything like scrap metals, or bits and pieces. But must have a place (to put the things) lah; if don't have, cannot do lor."

You can watch Jackson's documentary here, on Honour Singapore's Facebook page:

Top photo by Rachel Ng.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.