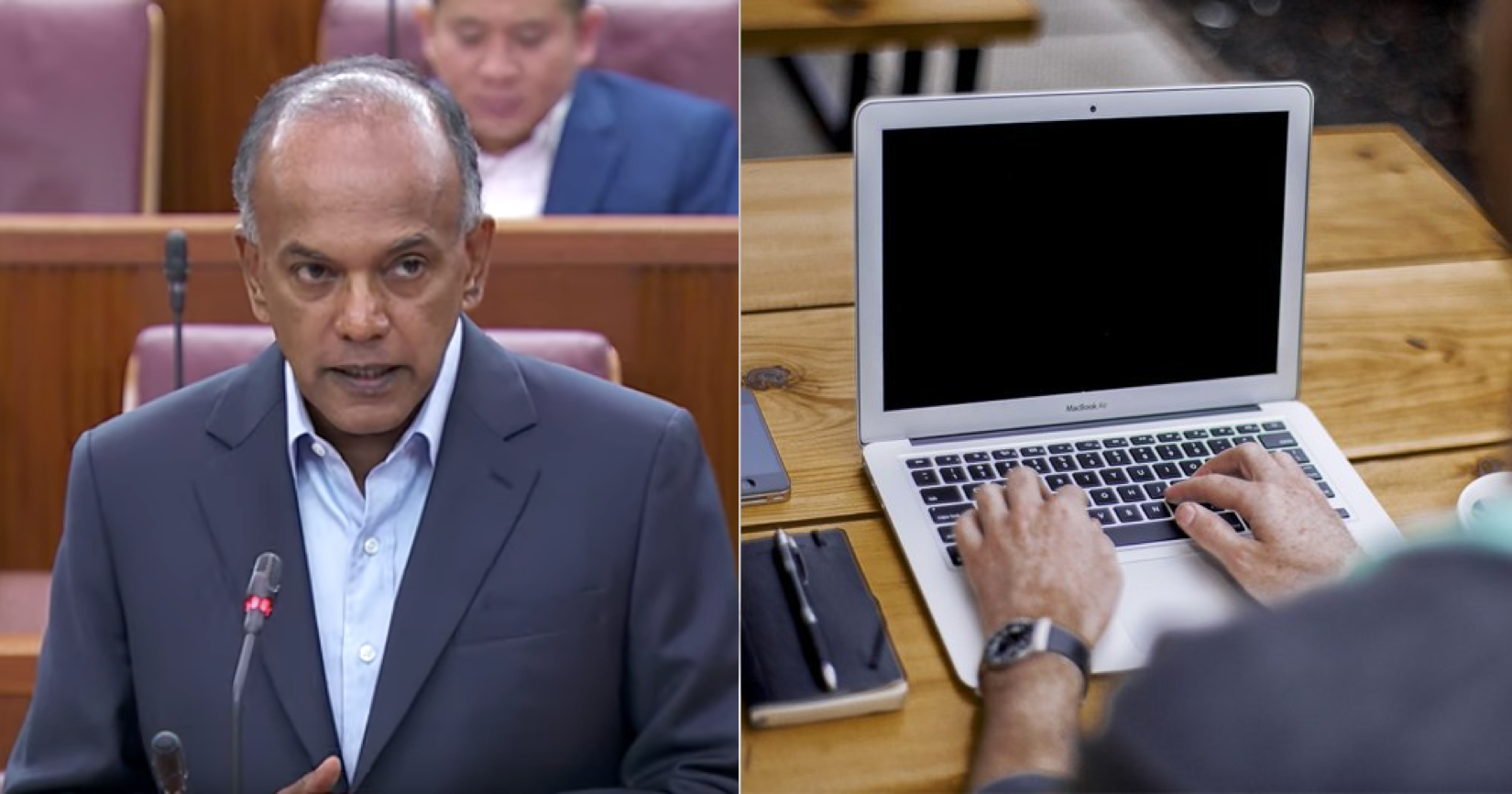

You may have noticed Minister for Home Affairs and Law K Shanmugam appearing in the media and online more frequently.

He's written a commentary piece, did an "online tutorial", appeared at dialogue sessions, gave exclusive interviews to mainstream media and even appeared with Michelle Chong's Ah Lian character in a video.

Second reading in Parliament

These efforts were made in the lead-up to his speech on the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill, which went through its second reading in Parliament on May 7.

It's a pretty big speech, with Shanmugam reiterating some of the points he or his colleague from the Ministry of Law previously made in the public debate over the Bill.

So let's break it down.

Existing powers

Shanmugam made the point that the government's powers under existing legislation are already wider than those in this Bill.

He pointed out that the Bill's powers only apply to false statements of fact, and must show that the falsehoods are against the public interest.

He then addressed four concerns that have been raised by various members of the public:

- Takedown of material.

- Said takedowns ordered by Ministers.

- Definition of public interest.

- Definition of falsehoods.

Shanmugam said that under the Broadcasting Act, regulator Info-communications Media Development Authority (IMDA) can already take down material online.

He added that there is currently no direct appeal to court, just a judicial review, and that the grounds for taking action in the public interest is wider.

Also, dealing with falsehoods is "not new" and the courts have done it before.

Compared to current laws, Bill provides more judicial oversight

Shanmugam highlighted the role of the courts in providing judicial oversight for the Bill. Currently, this is in the form of a judicial review.

However, the Bill allows for a direct appeal to court. Shanmugam said the process would be made "fast and inexpensive."

According to the Straits Times (ST), an appeal must be heard in six days after it is filed in the High Court, with no court fees charged for the first three days.

Courts have their own discretion to extend timelines or waive fees as they see fit, with the process of appeals to both the courts and the minister using standardised forms.

Why need a Bill?

Given the scope of current laws, Shanmugam said that the concerns could not be "logically increased" by the Bill.

So if existing laws already have these powers, why the need for a new Bill?

Shanmugam answered his own rhetorical question by pointing out that the Bill focuses specifically on online falsehoods, with "calibrated" remedies and greater judicial oversight.

He said that alternate paths, like amending the act through subsidiary legislation, would still result in broad powers with less judicial oversight.

Said Shanmugam, according to ST:

"If we had taken that approach, the result would have been an instrument with none of the calibration that the Bill proposes, or the judicial oversight which is also going to be made speedier."

This is because amending the act with subsidiary legislation would have been a blunt instrument with none of the calibration of the new bill proposed.

He noted that the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods had recommended new legislation, to provide the necessary speed, scope and adaptability to deal with the challenge of fake news.

Global trends and threats

So what are these challenges that require this Bill?

Shanmugam took a global view and described trends around the world, indicating that the public have lost confidence in institutions like the judiciary, the political system, businesses and the media.

He said it was important for both MPs and the public to understand the "big picture".

Institutions require trust and legitimacy to work. Without them, a vicious cycle is created that ends up weakening the fabric of society.

Compared to many Western countries, like the U.S., the Singapore public still maintains trust in institutions.

However, Shanmugam warned that global forces could impact Singapore too.

For political gain

Shanmugam then elaborated on sources of falsehoods.

Referring to actors who used online falsehoods for political gain, he cited an example from the UK during the referendum on Brexit.

A false claim was made that syariah law was enforced and there were "no-go" areas in some parts of the UK.

Despite being false, a survey in 2018 found that 32 per cent of 10,000 respondents believed it was true.

Shanmugam noted that hate crimes surged by 41 per cent after the referendum, due to the "permissive environment" created by falsehoods.

Shanmugam also pointed out that alt-right groups drove false narratives during the 2016 U.S. Presidential election campaign, and that far-right populist parties in Germany made gains in local elections after a false claim circulated that the police were covering up an assault on a girl by Middle Eastern immigrants.

For profit

Shanmugam noted that falsehoods can spread online for pure commercial profit.

He cited the example of Paul Horner, an American who earned up to S$10,000 a day from ad revenue from his 20 fake news websites.

One of them falsely claimed that actors were being paid to protest against then-Presidential candidate Donald Trump, which was re-tweeted by his campaign.

For military advantage

However, Singapore is also at danger from foreign countries using "information warfare".

Shanmugam said that although other countries may be "weaker" than Singapore in terms of military strength, they could focus instead on exploiting internal divisions and sapping the public's will.

According to ST, Shanmugam said that this was already happening, with people trying to weaken support for the Singapore Armed Forces or influence our foreign policy

However, he did not go into detail.

He added that if nothing was done about falsehoods, extremism becomes more likely as the political centre becomes "hollowed out".

Tech cannot be expected to self-regulate

Shanmugam said that technology companies provide the platforms from which falsehoods and other content are spread.

Shanmugam then went on to share examples from Sri Lanka and New Zealand that have shown clearly that the tech companies cannot self-regulate.

He noted the concessions made by Facebook, as he cited Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who said that regulation against harmful content is needed, as the problem is too big for Facebook to handle.

Expedited appeal

Shamugam shared how the appeal process against the direction will work.

1. Apply to Minister to cancel a Direction

- Minister must decide within two days of receiving application against his or her direction (by email)

2. Appeal to Court : The party to file within 14 days after Minister decides on above application

- Fill in a standard form, no need of lawyers

- Minister must file the reply in court within 2 days

- The Hearing will be held no later than 6 days after the Court receives the application

No court fees will be charged for the first three days.

The Court also has the power to waive the fees for further hearing dates.

Top image from Gov.sg's YouTube channel.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.