Ong Ye Kung's political career is marked by several significant highlights.

In 2011, he was part of the team that lost to the Workers' Party in Aljunied GRC. Four years later, he got through with the PAP's Sembawang team in the 2015 General Election, and subsequently, even became one of the three frontrunners to succeed PM Lee Hsien Loong.

Right after getting elected, his speedy climb up the political ladder has not gone unnoticed as well.

From Acting Minister for Education (Higher Education and Skills) in 2015, Ong was promoted to full Education Minister (Higher Education and Skills) a year later, and then last year, was appointed as sole Minister for Education.

He is also the only other 4G minister, apart from premier-in-waiting Heng Swee Keat, to helm the Ministry of Education solo.

Constantly improving things on the education front

Given that Singapore's world-class education system is constantly under scrutiny — by its direct participants and stakeholders (Singapore's citizens) no less — Ong bears great weight on his shoulders as Education Minister.

How does one constantly improve a system that is touted as one of the best in the world, but which is at the receiving end of relentless criticism and blame for overarching societal attitudes (ahem obsessive kiasuism, elitism, class divide, and to some extent, even racism)?

Ong took office three and a half years ago with Ng Chee Meng, and as with every Singaporean, Ong, too, had a personal wishlist for our education system, which he's been steadily working on in this admittedly short period so far.

So building on Heng's groundwork to reduce emphasis on grades, with Heng having pioneered "Every School is a Good School", Ong checked three things off his list. He:

- introduced an early admission exercise for polytechnics, allowing students to receive conditional offers for polytechnic admission based on aptitude-based assessments;

- introduced SkillsFuture in 2016, which is a step to his goal of encouraging all Singaporeans to make learning a lifelong endeavour; and

- reduced the number of school-based assessments at the primary and secondary level, including the removal of Mid-Year Exams at selected Secondary and Primary levels (removal of Mid-Year Exams for Secondary One students has kicked in this year!).

But the most recent step Ong took and pushed through at this year's Budget and Committee of Supply debates is his biggest-ever so far, and that's customising the curriculum for students to work at every subject they take to their individual strengths.

Enter subject-based banding (SBB)

Ong announcing the SBB system in Parliament. Screenshot via Gov.sg YouTube video

Ong announcing the SBB system in Parliament. Screenshot via Gov.sg YouTube video

If the extensive discussion that's taken place since Ong announced this about a month ago is anything to go by, this initiative is likely to be among the most ambitious changes ever undertaken by MOE.

To be fair, it's been more than two decades in the making — this was first rolled out in primary schools in 2008, alongside the scrapping of the EM3 stream, after EM1 and EM2 were merged in 2004.

After witnessing its effectiveness in reducing segregation based on which stream different students were in, the effort began to move this upward.

In 2014, subject-based banding in secondary schools was first introduced in 12 pilot schools. Continuing this trajectory is an expansion of subject-based banding across all subjects in 25 pilot schools, starting from 2020.

The motivations behind SBB? Ong explains that it is to inject more flexibility into the secondary school system so every student in Singapore can work on their strengths and weaknesses at varying levels.

"When you post a student into a course and you say that this course is the less difficult one, after a while, the child may start to have a self-limiting mindset. Many of our teachers encounter such students.

While SBB is constantly encouraging that growth mindset — for a student to study subjects they are strong in at a higher level, and to be prepared to learn something they are not good at, but (which they) can get better."

All schools — yes, even Express-only, SAP & IP schools — will benefit from offering G2 and G1 subjects

Certainly, the scrapping of the Express and Normal (Academic) and (Technical) stream system has given rise to many concerns and questions.

Not wanting G3 kids to mix with G2/G1-level students

We've seen parents who say, I don't want my G3-qualified kid mixing with G2 and G1-level students, and so I'm going to try my best to get them into schools that only offer G3-level subjects — or better still, schools on the integrated programme (IP).

Ong looks pretty cognisant of this, and when we ask him about these groups, he mentions in at least three instances during our conversation that every secondary school in Singapore — Express-stream-only, SAP and IP schools included — will benefit from subject-based banding.

“Some students are crazily talented and are all-rounders,” he says, "but the great majority have uneven strengths and specific weaknesses."

"I would strongly encourage schools that are currently only taking in Express students to also offer some G1, G2 level subjects," he says.

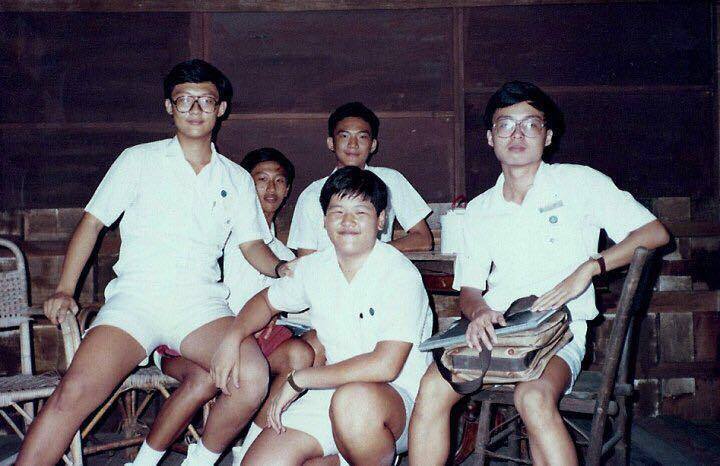

Ong, during his secondary school days. Photo via FB/Ong Ye Kung.

Ong, during his secondary school days. Photo via FB/Ong Ye Kung.

He has also said before that even though he went to Maris Stella High, a SAP school, he struggled greatly with English, and subjects that were English-language-heavy like literature, history and geography:

“My history... I didn’t know what the teacher was saying most of the time! I could read the words in the textbook but I didn’t know what they meant. It was so difficult. I just memorised whole chunks of text, looked at the (exam) question, looked out for similar words, and just reproduced the chunks.”

English, he says, was his "Achilles' heel", and so by extension, he wishes he had the chance of experiencing subject-based banding as a student:

“I thought I would have benefited if I was able to study English at G2 level... learn the basics at that level, then if I could make it, (progress) to G3 after that.”

That being said, Ong points out that the group of parents who fight tooth and nail to get their children into IP schools won't be impacted by this new system anyway.

"These parents do exist. But these are the same parents who would push their children to go to IP schools today anyway!"

Transferring stress to PSLE

Would this system also, by extension, transfer stress to the PSLE experience?

Ong doesn't seem to think so either — in fact, he declares subject-based banding will help reduce PSLE stress:

“Today, even if you don’t do so well for PSLE, you can still prove yourself in Sec One and do a bunch of G1 to G3 subjects.”

An operational multi-year migraine

Part of the team that worked on the ‘one secondary school education, many subject bands’ policy. Photo via FB/Ong Ye Kung.

Part of the team that worked on the ‘one secondary school education, many subject bands’ policy. Photo via FB/Ong Ye Kung.

Ong thinks the immediate challenge facing the Ministry — with regard to the implementation of SBB — is an operational one, though, beyond the need to change mindsets.

Timetabling, for instance, will be a definite problem. All schools will inevitably have to undergo the struggle to customise an optimal combination of classes for each student.

And we haven't even gotten into how admissions for post-secondary education courses will be done — there are no details available on that yet, and the ministry will also have to iron those out if they haven't already gotten cracking on it.

Despite these obstacles that lie ahead, Ong shares that he draws strength from the backing he has received from teachers and principals:

“I can’t announce this without the wholehearted support of principals and teachers. I was prepared to push for this because many principals and teachers told me that this would be the right thing to do…

I think this is what mattered.”

Slaying the PSLE cow? Not in my lifetime, says Ong

As we speak about other issues such as the PSLE, Singapore's frighteningly huge tuition culture and industry, and even how Singapore's education system compares to other well-regarded systems in the world, one thing becomes increasingly clear to us.

As much as Ong is a politician, his priority in policymaking is not what the people want (or, arguably, what he wants) but, he keeps saying, what is "educationally sound".

Will we ever see Singapore phasing the PSLE out completely? Ong's answer is no, he doesn't see this happening within his lifetime.

He acknowledges that the PSLE is stressful but despite its range of flaws, he cannot envision a better (and more objective) system that will offer students the same possibility of choices.

He volunteers the Swiss system, where students mostly end up in the school nearest their homes (barring, of course, those rich enough to send their children to private school), and Hong Kong, where students are assessed at age 11 (transferring the stress upstream, to his mind), to show the trade-offs in systems that do not have an equivalent standard national exam at age 12.

“I cannot see what other systems, apart from PSLE, would be better in assigning students to their (secondary) school… It is still the most objective way for a child to go to a school of his or her choice. You work hard, do well in the exam, and you can go to the school of your choice.”

Ong Ye Kung, Singaporean dad

Photo by Rachel Ng

Photo by Rachel Ng

Throughout our chat, Ong speaks about education from the standpoint of a minister — which he of course is; the minister. But when he's not wearing his minister hat, he pretty much is your regular Singaporean dad who wants the best for his children.

His push for a de-emphasis on grades notwithstanding, Ong says that he does ask his two daughters about their grades (they will not get to experience the new SBB system, by the way).

That being said, he stresses he is "not overly anxious" and instead, only hopes for them to do their best.

He also candidly reveals that he isn't against tuition, especially if it can enrich a child's learning.

This then prompts our question: what are the circumstances under which he would send his daughters to tuition?

"Only when they asked for it," he says gently — yes, even if they were failing, he would only do so if they asked.

“It is a life skill to ask for help when you need to; to overcome difficulty for something you cannot cope with.”

And that's why he doesn't feel that his ministry needs to curb tuition-going at this point — if students want and need it, they should be able to access it.

But at the same time, he feels that an obsessive tuition culture will be counterproductive for all children:

“If they need help through tuition or enrichment, then it is beneficial. But when it’s obsessive, it becomes negative because you’re taking away childhood time from the student, which they can use to play, explore interests, develop their social and emotional skills. You may also inadvertently undermine their ability to self-learn…

That will not be healthy.”

Fielding international curiosity, sharing notes & adapting features

Photo by Rachel Ng

Photo by Rachel Ng

All this being said, Ong thinks our education system is "well-regarded in the world".

Just last week, he shares that he hosted representatives from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, who took special interest in what he was doing — his most recent changes in particular.

Also, he often gets queries from ambassadors and educators from different systems wanting to know more about the motivations behind Singapore's education policy changes.

Take earlier this year, for instance, where Indonesian media incorrectly reported that Singapore was scrapping all its exams and triggered frantic calls from Ong's government counterparts asking what, why and how.

"I understand that my announcement on reducing the number of school-based assessments created a stir in Indonesia because the news was wrongly translated to ‘Singapore abolishes all exams’. It caused a huge public debate there. Recently, I went to Indonesia, there were so many people who wanted to talk to me about education asking, ‘Why did you remove all exams?’ I said I didn’t!”

And how can Singapore's education system learn from other systems in the world, like Finland's and Switzerland's, for example?

He calls Finland a good friend of ours, saying he often shares notes with them, and in Switzerland, only 20 per cent of its people go to university — the bulk go to vocational schools, and that's seen as a perfectly respectful and noble pathway that leads to mastery in specialised craft and trades.

Ong admires both of these, but is also deeply mindful that their features cannot be copied wholesale — his ministry ultimately has to do what works best for Singapore.

"Education systems exist within a cultural context," he says.

Designing a system that counters, not aggravates, inequality

What keeps Ong up at night is a very big concept that we find tough to grasp, but which we attempt to articulate as this: his role in shaping Singapore's social consensus.

It can be said that underscoring all of these changes Ong has made to the system in his short time here thus far is his obsession in helping every child in Singapore to fulfil their potential.

In his vision for the future of Singapore's education system, Ong also sees a post-secondary system to develop various individual skills, and then a lifelong learning system to deepen and enhance them.

"To do a craft well, you must be guided by passion. You must be able to hone this your whole life, to master your craft. So, how does our education system prepare someone for that?

First, learning must be fun. Second, there must be space for one to work hard and to also discover what they’re good at.

And this system must also recognise that some people have singular strengths, and give them the opportunity to develop that strength to the fullest."

Ong is acutely aware of the difficulties in making this happen. But seeing how he has boldly and systematically moved to phase out streaming at all levels, he is clearly not easily fazed by challenges.

When we ask if he has any other big education-related projects on the horizon (ahem, items on his wish list), Ong cheekily responds: "Phasing out streaming not big enough ah?"

Even though he is coy about elaborating further, Ong hints that there still is room for our education system to signal changes in mindsets and better-prepare every student passing through our system for the future.

Just like how the move for employers to look beyond grades as a tool to assess job applicants is a signal to parents to obsess a bit less about them, we can see in Ong a quiet hope that his efforts will eventually assist in moving Singapore in that direction.

But of course, what he says next reminds us that he is certainly still quite grounded in reality:

"We can make some changes to signal to the wider society, as a suggestion to move towards a general direction. But society can also reject our ideas.”

What he leaves us with, though, we choose to see with hope for the children we may also have some years down the road.

"I have a few more things I would like to do," he concludes with a grin.

Top photo by Rachel Ng.

Related stories:

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.