In case you haven't heard, last week (March 7) Watain — a Swedish black metal band infamous for their satanic beliefs and ritualistic performances — had their concert in Singapore cancelled.

A petition that garnered more than 19,000 signatures had preceded the cancellation. It called for a ban on “satanic music groups”, insisting that “these heavy metal bands do not represent the culture which we want in our youths”.

This has sparked much debate and many questions about the supposed evils of metal and black metal in particular. What kind of people would even want to attend a gig where animal blood is sprayed on the audience? Does listening to black metal instantly turn you into a violent slave of Satan?

Seeking a better understanding of the type of music in question, we were led to 41-year-old Gabriel Deen — the closest thing Mothership could find to a professor in metal.

Having first been introduced to heavy metal music as a young boy in primary school, Deen tells us that he soon found himself “neck-deep” in black metal music — both as a fan and as a practitioner.

Under three different stage names — "Odhinn", "Kyng Hades Almighty", and "Deadwax" — Deen has fronted a handful of black metal bands since the early 2000s. The last band he was involved in (a brilliantly-named Funeral Hearse), had even been signed by an American recording company called Redefining Darkness Label as recently as two years ago.

A veteran of the local metal scene, Deen also owned and ran a studio and music shop out of Peninsula Shopping Centre called Tomegatherion — a place dedicated to metal music that also served as a hang-out spot for many Singaporean metal fans (or metalheads, as they like to be called).

Deen in corpse paint, courtesy of Gabriel Deen

Deen in corpse paint, courtesy of Gabriel Deen

A regular family man

With all this in mind, imagine our shock when, standing outside his HDB flat, my colleagues and I are met with a poster featuring a Bible verse from Psalm 23 pasted on the doorpost — "The Lord is My Shepherd I shall not be afraid," it reads.

“This can’t be it,” we say to one another. And just as we’re looking around at the other unit numbers, Deen appears at the door and greets us.

As he lets us into his house, it quickly becomes apparent what we’re dealing with here. There is no altar to Satan, nor are there blood spatters on the floor from animal sacrifices. I probably didn’t even need the Bible I’d snuck along in my bag for protection.

On the contrary, Deen is warm and friendly; joking around and asking us to make ourselves at home as he pours us some drinks and heats up some curry puffs.

I didn’t think much of it at the time, but he had warned me of this over WhatsApp before we met: Deen, the black metalhead previously known as Kyng Hades Almighty, is just a regular family man. And as the scriptures and Christian posters hung up all over his living room suggest, he’s also a man of (staunch, if we might add) faith.

But before I can ask him about the posters, Deen is over at his desktop computer recommending different bands to me. He’s buzzing with energy as he reels off a list of metal bands.

“Bro, you got to check this out. You’ll love it, trust me.” He says this about several different bands and proceeds to play their music for me. It’s very hard to keep up but such is his enthusiasm and passion for the music.

Low growls and shrieking vocals

Deen recalls King Diamond’s 1988 album "Them" as the first heavy metal album that really caught his attention as a 10-year-old boy.

“It had a track called Phone Call,” he says. “I was scared sh*tless”.

The track is not a song per se, but more of an audio skit. In it, King Diamond receives a phone call from his deceased grandmother who has come back to haunt him. I can personally confirm that as a 25-year-old listening to this at near midnight, I, too, was scared sh*tless.

But beyond being frightened, Deen was hooked and it wasn’t long before he delved into more extreme forms of metal music. In 1993, he got his hands on his first black metal cassette tape — the eponymously named debut from Swedish black metal band Bathory.

As Deen goes on to explain, "extreme metal" is an umbrella term that encompasses a number of heavy metal sub-genres. Bands that fall under the genres of

- thrash metal,

- death metal,

- doom metal, and of course

- black metal,

are all considered extreme metal bands.

It might all sound like metal to the uninitiated, but each sub-genre is seen as very distinct from the others, especially by metalheads.

According to Deen, one of the big distinctions is the themes of the music. For example, death metal — which initially found popularity in Florida, USA, with bands such as Morbid Angel and Deicide — tends to cover themes such as war, poverty, and politics.

On the other hand, black metal, which finds much of its cultural origins from Scandinavia with bands such as Bathory and Mayhem, has come to be associated with Satanism, paganism, and the occult.

Deen showing us some music. Photo by Rachel Ng

Deen showing us some music. Photo by Rachel Ng

Deen adds that there are also sonic differences when it comes to the genres. For instance, while death metal tends to employ low growling vocals, black metal music usually features high-pitched screaming singers.

Black metal also characteristically focuses heavily on setting an atmosphere, famous in its utilisation of the tritone — the musical interval that has come to be nicknamed "the devil’s interval". You can listen to it here:

It’s this musical sleight of hand that gives black metal its dark and evil-ish sound.

Deen himself is specifically a fan of black metal, recalling the feelings that gripped him as a secondary school student when he first heard it.

“I was just so blown away by this new sound. And it was just so lo-fi. Very distorted guitars, and shrieking vocals.”

Unfortunately for him, though, this love of heavy music was not something many of his peers shared.

“I remember when I was in Primary Four, our music teacher told us, ‘all of you can bring something that you like to listen to, to play in the music class’. So I brought this cassette tape — King Diamond — I played it, and I started to head bang. All the other kids were like ‘Oi! What is this?’ They didn’t understand.”

Comfort and community

As I’m listening to Deen recount his experiences as a young metalhead — in his words: “I was persecuted as a kid for listening to metal” — it begins to dawn on me that the music might have something of a double reinforcing effect.

While metalheads are ostracised for the music they love, it’s also in this music that they find comfort and community. Perhaps that explains why the genre sparks such loyalty and devotion.

“When I was a kid — when I was bullied or when I was abused, when I had nowhere to go, no parents to share my feelings with — metal was the only thing that kept me sane. Even my grandma would scold me. She said ‘are you mad? Why are you listening to this kind of music?’”

Coming from what he describes as a broken home, and living mostly with his uncle and grandmother, Deen often found himself jealous of other kids and their families. Metal was where he found his solace.

“Metal was everything I had. Metal was something which I felt was listening to my grievances as a kid.” The emotion in his voice becomes more apparent, and his gestures grow bigger and bigger.

It's plain to see that Deen is overflowing with passion for metal music. And it’s this passion that connects metalheads to one another.

“Only in a metal gig, all these fans — no matter from which backgrounds they come from — they come together. They enjoy the music and they forge friendships.”

In metal, the fans find a camaraderie and a community that escapes them in every other social setting. At school, Deen was the weirdo kid who listened to far-out music. In the metal scene, he was Kyng Hades Almighty — frontman of Zushakon — whose music was appreciated, celebrated even, by other metal fans.

Deen, left, and a bandmate. Courtesy of Gabriel Deen

Deen, left, and a bandmate. Courtesy of Gabriel Deen

All the elements that make black metal so inaccessible to the lay person — the underground gigs, the ‘all-black-with-spikes’ aesthetic, and the dissonant music — they all come together to form an insular universe of sorts. It creates a sense of belonging amongst people who feel excluded.

Where does Satanism come in?

There is a big question that’s lingering over this image of a tight-knit community that Deen has painted for me, though — why does Satanism seem so integral to black metal music?

According to Deen, the Satanism implicit in black metal music had its beginnings not so much in devil worship, but a desire to be different. “In Norway, what happened was there was a disdain for mainstream living by this group of kids,” he explains. “They were just kids!”

In the late 1980s, these teenagers who came from privileged, white, middle and upper-class families, had gotten bored of mainstream culture.

“They felt that death metal had become too sell-out. It was so open and commercialised. They wanted to create something special.”

At the forefront of all of this was a Norwegian teenager, known by his stage name "Euronymous", and his black metal band called Mayhem. In an effort to set themselves apart from the mainstream, these Scandinavian teenagers branded themselves as Satanists who hated, among other things, Christianity.

Many of the tropes associated with black metal were also adopted by bands around this time: corpse paint (like in Deen's old band pictures), black leather, and spikes.

Photo by Rachel Ng

Photo by Rachel Ng

“They just wanted to be despicable to religious people. They wanted to taunt the very conservative religious people in Norway. So they decided to make use of Satanic images.”

There is some level of doubt over whether any of these bands truly practised Satanism. In fact, Varg Vikernes — who is himself known for both his seminal band Burzum and the murder of the aforementioned Euronymous — has claimed that the connection between Satanism and black metal was largely perpetuated by Scandinavian tabloids.

A large part of the Satanic imagery and rituals in black metal, Deen adds, has also been attributed to shock value, theatrics, and scare tactics.

Whatever the case, Deen believes that, at least in Singapore, black metal fans aren’t so sinister.

“Singaporean metal fans — they’re harmless. They don’t go around wanting to stab people or sacrifice babies.”

Disdain for the mainstream

What does carry over from the Scandinavian pioneers of black metal, though, is a contempt for all things mainstream.

“True black metal,” Deen says, “don’t play to the mainstream. They don’t want to be in the magazines; they don’t want to be on the radio.”

As he delves into the topic of the mainstream society, though, I notice Deen’s eyes widen. Both his fists, held in front of him, are now clenched. “Even I feel it now, as I’m talking to you, all this hatred I have for the mainstream society.”

“Why do I listen to black metal? I listen to black metal because I am against mainstream society. Of how they are so bigoted, how they are so hell-bent on hunting people down who don’t subscribe to their ideals and thinking. Also, people who like to look down on others — racists.”

It’s quite a jarring to see Deen like this. For most of the interview he’d been laid-back — clearly passionate about the music but at the same time good-humoured and relaxed — but all of a sudden there is a fire in his eyes; an intensity to his words, and he's even beating his chest.

“When you play the music as a musician, you are a different person,” Deen says as his face begins to contort into a grimace. “It's more like Jekyll and Hyde — you know the other side coming out. All your frustration, all your anger, you know? All your hatred for mainstream society.”

So were the petitioners right then? Does mainstream society have reason to fear the aggression that black metal seems to promote amongst its adherents?

“Metal has never been a reason, to make me want to kill somebody or hit somebody,” replies Deen.

“You are letting out what you have inside your heart and your mind. It’s the outlet of music”, he says, explaining that metalheads use the music as a sort of therapy. “Why would you want to be aggressive outside?”

Can Christianity and a love for black metal coexist?

These days, Deen no longer dons corpse paint, nor does he front any Satanic black metal bands. Instead, he spends a lot of his free time with his 15-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter.

His conversion to Christianity in 2013, he quite candidly shares, has also left him ostracised by most of the black metal community that once embraced him. “I was persecuted as a Christian by my own friends from the metal underground,” he says.

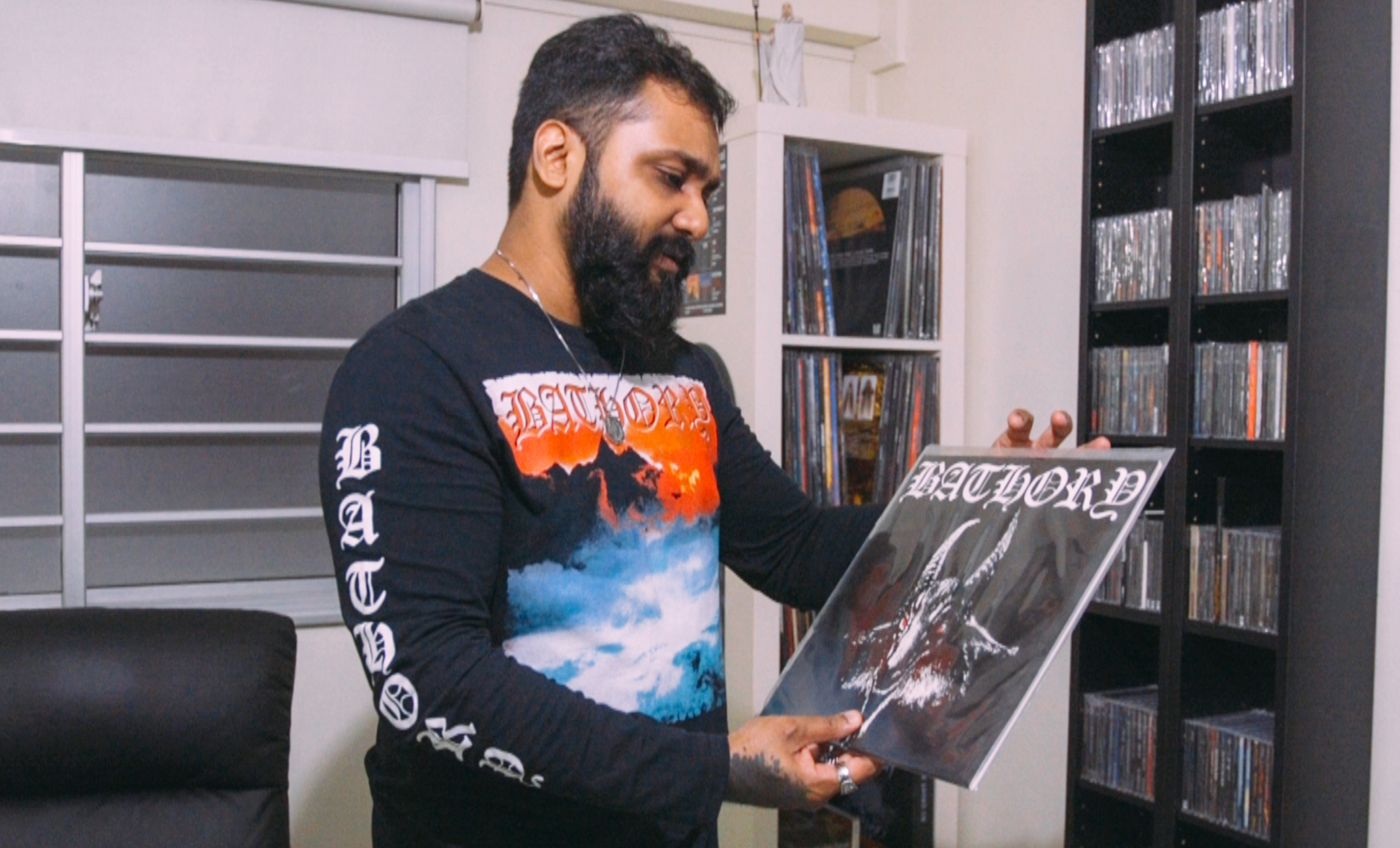

Deen with one of his favourite Bathory records. Photo by Rachel Ng

Deen with one of his favourite Bathory records. Photo by Rachel Ng

The dichotomy of Deen's previous life with his newfound faith is hard to ignore. He's still very much a metalhead, albeit one well aware of the tension between being a man of faith and man of (this particular type of) music.

As recently as in 2017, after all, he was the vocalist of Funeral Hearse — releasing songs with titles such as "Master Judas Underground". But he later on quit the band.

"I knew that I didn't want to project a hypocritical self. To the metal world, I'm playing black metal. But in my heart I don't believe in the anti-Christ or his grandma anymore."

He’s now more selective about the kind of black metal he listens to, avoiding bands whose lyrics he deems too offensive, especially those who go big on Satanic imagery.

“I started to feel that in a society such as ours, I think it’s a little bit uncomfortable.”

However, asked about the long-sleeved shirt he’s wearing — a Bathory shirt with five Satanic goat heads running down one sleeve — Deen is unapologetic.

“I mean Bathory is a great band. For me, forever. Forever Bathory,” he says.

“Bathory is in my blood.”

Top left photo courtesy of Gabriel Deen, right photo by Rachel Ng

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.