When 22-year-old Shanti Pereira won a gold medal in the 200m sprint in the 2015 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games, she broke a 42-year-old record last set by one Glory Barnabas.

She also broke a 36-year-old dry spell of track golds clinched by Singaporean women at the Games ever since long-distance runner Kandasamy Jayamani took home two (and set two still-unbeaten national records in the process) in 1979.

Now, these two names of our longtime record holders — Glory Barnabas and K. Jayamani — might not ring a bell for most of us today, but the two of them are, and were, legendary sporting icons — especially in their heyday in Singapore, in the 1970s and 80s.

And in honour of their contributions to the Singapore sporting scene, both Barnabas and Jayamani, now a ripe young 77 and 63 respectively, were last weekend inducted into the Singapore Women's Hall of Fame.

K. Jayamani (left) and Glory Barnabas (right). Photo by Rachel Ng.

K. Jayamani (left) and Glory Barnabas (right). Photo by Rachel Ng.

Gold medal Glory

Glory Barnabas. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Glory Barnabas. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Barnabas is best known for her double gold medals in the 4x100m and the 200m races at the 1973 SEAP Games — the first-ever international sporting event held in Singapore.

The then 31-year-old was a dark horse that nobody expected to win.

Aside from being not as young as one might expect an athlete at their peak condition to be, Barnabas had never won a gold medal at an international meet prior. She had previously chalked up three bronzes in the 1967 SEAP Games, and another three silvers in 1969 but the gold medal always stayed slightly out of reach.

Added on to that was the fact that Barnabas had stopped competitive running and training for three years from 1970 to focus on her teaching career.

But, sitting down to an interview with Mothership recently, she tells us she thought since Singapore was hosting the Games, it would be her last chance to try for an international gold medal for the country.

That being said, the thought of competing against runners who were much younger than her of course had her worried:

"Everybody expected one of the Burmese girls, Than Than, to win, and they were all talking about her. She was in Lane 1 while I was in Lane 3. Keeping her as a benchmark, I just tried to keep up with her. As we came round the corner, to the last 100m, I saw that she was one metre ahead so I ran as fast as I could and at the finish line I just lunged forward."

She had anger as a driver working in her favour too — not long prior, at the opening of the Grand Old Dame two months prior to the SEAP Games, the late and then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew said Singapore wasn't interested in medals, just in getting Singaporeans to engage in sport as a lifelong pursuit.

"We, the athletes, were so angry. We were going for medals. The girls were all worked up: 'We must show him!'"

And show him she did — she lunged, it was a photo finish. The crowd roared, and for Singaporeans that day, winning a gold medal was especially sweet since it happened on home ground.

The Straits Times called her "Glorious Glory" while New Nation trumpeted her win as a shock victory for Singapore.

Adapted from NewspaperSG.

Adapted from NewspaperSG.

From Glory fan to making own gold medal history for Singapore

But perhaps the person who Barnabas's win made the most impact on was 18-year-old Jayamani, who was cheering for her idol among the euphoric crowd that day, and hoping to similarly one day make her mark on the international stage.

"By then I was already in the training squad (for the national team). In fact, when our seniors were training for the SEA Games, I used to go and join them. I used to train with the long-distance group," says Jayamani.

She did not need to wait long. Four years later, Jayamani took home her first gold medals (Singapore's first in those events, too) at the 1977 Kuala Lumpur SEA Games, in the 1,500m and 3,000m races.

It was an incredible (apart from being historic) feat, especially bearing in mind that the 1977 Games was her first-ever.

"I was competing against experienced girls from Indonesia, Myanmar, and Malaysia and they had already taken part in at least two SEA Games. It was not easy for me.

But my coach said 'Never mind, you just follow them as much as you can. You still have a chance; it depends on how you're going to run the race.'"

K. Jayamani. Photo by Rachel Ng.

K. Jayamani. Photo by Rachel Ng.

So as the 1,500m race started, Jayamani tried to keep as close as possible to her opponents and paced herself according to their speed.

It was at the last 200m that Jayamani broke free from the group and sprinted as fast as she could to the finish line.

"It was like oh my God! Beating those experienced girls was not easy, and I was so very very happy."

Via NewspaperSG.

Via NewspaperSG.

In the subsequent 3,000m race, Jayamani employed the same strategy except this time, she waited until the last 100m before she broke free of the group, beat Filipino "Bionic Girl" Arsenia Sagaray, and claimed her second gold medal.

Her records still stand, 37 years on

Jayamani went on to not only defend her twin titles at the 1979 Jakarta SEA Games, but in the 1983 edition, even struck yet another historic gold in the women's marathon. She was also the first Singaporean to win at the SEA Games marathon.

No woman has yet been able to repeat her gold-medal success in any of these three events.

Yvonne Danson would 12 years later shave 28 seconds off her 3:02:46 timing, but to date, Jayamani is still Singapore's only female marathon gold medallist, and her 1,500 and 3,000m timings from 1982, by the way, are still unbeaten national records.

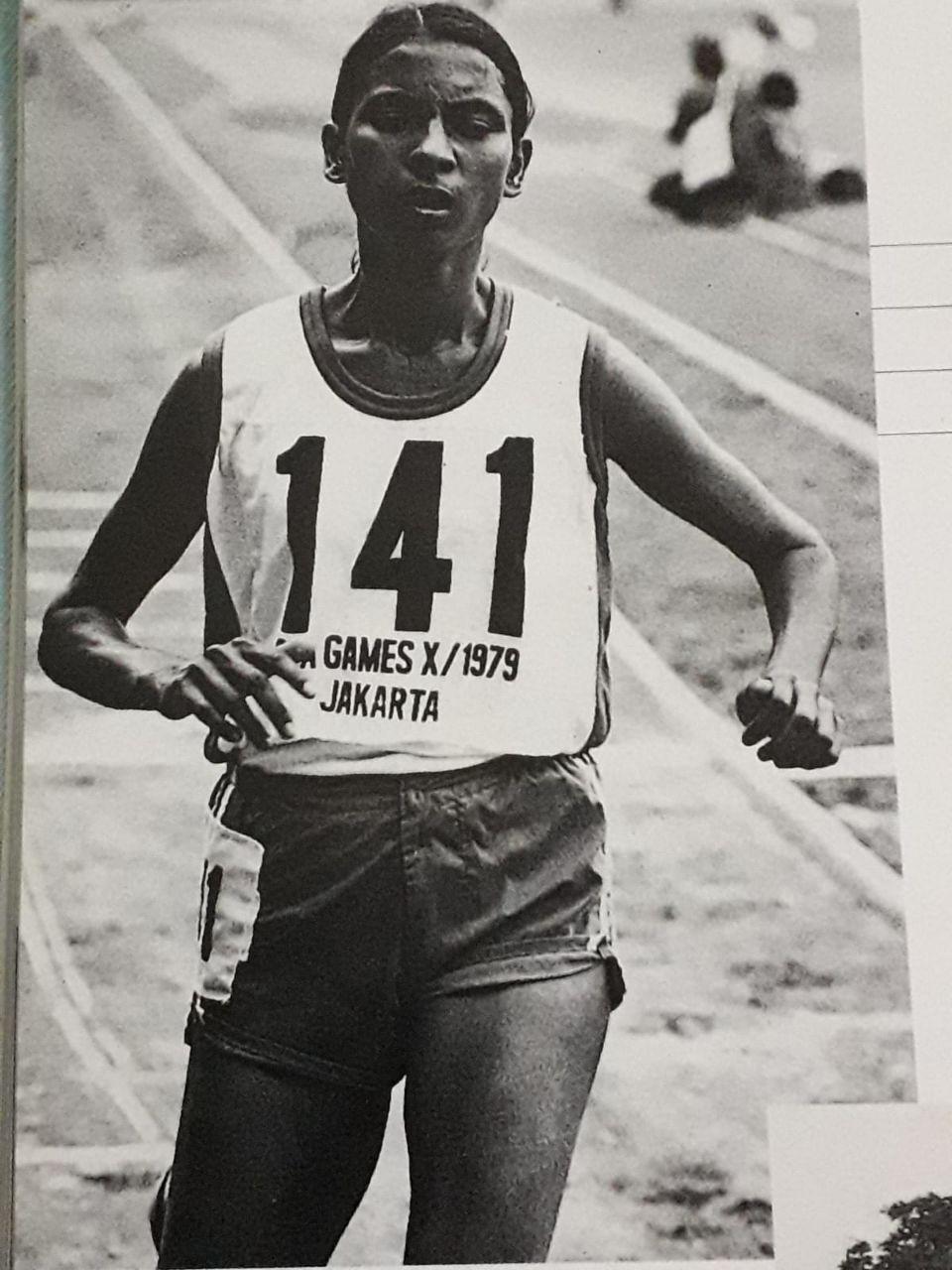

Jayamani at the 1979 SEA Games. Courtesy of K. Jayamani.

Jayamani at the 1979 SEA Games. Courtesy of K. Jayamani.

Jayamani's journey: from brisk-walking to long-distance running

For Jayamani, sports was always a family affair. Her father and sisters were into sports. From badminton to volleyball to basketball — you name it, she's played it.

"For me it was not difficult. My father and two elder sisters were into brisk walking and slowly I did it too. I also took part in school sports. My father allowed me to take part in all types of sports."

She started competing in sports meets when she was 13, first as a competitive walker and then running in 1,500m races. She found that she was pretty good, often placing in the top three, and was spotted by Maurice Nicholas, the coach of a local sports club.

"He said to me, why don't you take a day or two days to come run at Farrer Park Stadium," she explained.

Medals that Jayamani won during her childhood. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Medals that Jayamani won during her childhood. Photo by Rachel Ng.

From then, she started to train as a long-distance runner under Nicholas. Over time, she started to devote more of her time to running in sports meets and cross country runs instead of competitive walking.

Training alongside male runners

Jayamani says her training under Nicholas was rather unique.

"I was a rose placed among thorns," she laughs. "He placed me among the boys to run and my goal was to keep up with them. The idea is to push myself and meet the target time."

Her training took place in the morning on her own and in the evening at the Farrer Park Stadium track where she did time trials, laps, and dashes to train her stamina.

Nicholas, she says, was a strict but very caring coach.

"He was strict in the sense that made sure we reached our target time. If you don't, he would tell you that you're not putting in enough effort otherwise you're not going to go anywhere. He won't shout but he will give sensible advice."

Barnabas's journey: from netball to sprinting

Barnabas was also talent-spotted early.

"When I was in school, I was a very good netball player. Somehow, they found me to be very good as a runner because I had the speed. They made me the centre player. That was my first love."

Barnabas was also often fielded by her school in district sports day competitions where she took part in 4x100m relay races.

"So my teachers would pick us up — myself and a few others — drive us to another school and take part in their races," she says. "That's how I got started."

After graduating from secondary school, Barnabas enrolled herself at the Teachers' Training College. By then, almost all her free time disappeared and, being the practical Singaporean she was, she decided to give up sports to concentrate on her training.

Two of Glory's gold medals. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Two of Glory's gold medals. Photo by Rachel Ng.

However, in 1962, during her second year in teacher's training, a chance encounter reignited her passion as an athlete.

That year, the training college organised a sports meet at Farrer Park Stadium.

A miracle comeback

On the day of the meet, one of the relay sprinters fell sick. Immediately, her team mate phoned Barnabas and asked her to replace the girl.

"I had no training whatsoever, no warm-up and landed at Farrer Park. It's a wonder I didn't tear a muscle," Barnabas laughs. "And instead of making me the first or second runner, they made me the last runner!"

Nevertheless, Barnabas took on the challenge and ran:

"When I got the baton (at the fourth leg of the race), I was last! But I managed to run through and we became first. It was so exciting — from last to first!"

Immediately after the race, the late national coach Tan Eng Yoon, who was also a lecturer at the Teachers' Training College, took Barnabas aside and said, "Glory, you will now start coming for training every day."

Training under Tan was tough. She had to practise her starts, and ran multiple laps ranging between 200m and 400m — and this was daily, from 4pm to 7pm at Farrer Park Stadium.

However, if there was one thing she learnt, it was that training does not always guarantee record-breaking times. For a sport where one millisecond determines success, there is a plethora of factors that affect performance.

"That's the thing about training. You can never do the best time every time even though you know you put in a lot of hard work, you've taken your meals properly, you've had rest, still it does not work. There's going t0 be a point where you hit a plateau."

"You can get 13.1, 13.3, 13.4 seconds for a long time," she says, "and suddenly out of nowhere you hit 12.9. It happens that way."

Singaporeans haven't been able to replicate success because they're distracted

It's not a stretch to say that things were much tougher for athletes in the past. They had no world-class facilities or sports science, much less a specialised sports school to help athletes reach their peak condition.

Even the spikes on Barnabas's and Jayamani's shoes were manually nailed in at a tiny shop in Selegie.

"Now it's all high class — Brooks, adidas, Asics. During our time we had to screw in the nails," Barnabas smiles.

So if athletes have it better today, why do we not see a repeat of Singapore's golden generation of track and field athletes from the 60s and 70s?

Barnabas's take is Singaporeans today are distracted — by the paper chase, for example:

"Parents today want more from their kids. They don't want them to spend too much time outside of their studies. The main thing is still your studies because that's going to get you somewhere, not sports and stuff like that.

Students are at a loss. To do well you cannot just do the minimum training."

Barnabas says athletes need to have C.P.F. — Commitment, Perseverance, and Focus — without these, a full-time athlete will not be able to reach peak performance; never mind a "part-time" one.

"A one-hour training is not enough. You need to train twice a day, four or five hours or so. You need to put in the time. But parents are afraid their studies will suffer... At the end of the day, it's paper qualifications that matter," she says with a slightly sad smile.

But this isn't to say that studies aren't important, Jayamani adds:

"During our time, an O-Level can still get you a job, but today, you need a degree."

Back then, young athletes didn't have much in the form of entertainment to distract them.

"We work, we go to track, and we come home. We didn't go to see the pictures for entertainment too," Jayamani says.

"Today there's so much on the internet, and so many games. So youngsters might question why they need to torture their bodies to train when they can enjoy their games instead!"

Coaching, teaching & now still giving back

Today, both ladies are perhaps not as fast as they were in their heydays, but they are still running, and they're not just giving back to the sport they made history for Singapore in — they're also making a difference in society, in their own small ways.

Jayamani coached a little after retiring from competitive running in 1992 with the Singapore Athletics Association, and then continued on her own as a track instructor in various schools like Anglo-Chinese School (Independent) and CHIJ St. Joseph.

That stopped in 2008 after she decided to become a full-time as a caretaker for a boy who has autism:

"My initial goal was to be a coach as a way of giving back — and I did it along the way. But things changed. Now I'm still coaching in a way and giving this child the best he can get to become independent."

Meanwhile, Barnabas taught at various schools including Mountbatten Primary, Willow Avenue Secondary, and went on to set up Tampines Junior College's Physical Education department. She still relief teaches from time to time, by the way.

And although she left the national team in 1977, she remained active in competitive sports and continued winning on the world stage.

In 1987, at a sprightly 45, Barnabas won a gold medal in the 200m sprint at the World Masters Athletics Championships — a competition for athletes above 35 — in Melbourne, Australia.

More recently, aged 71, she picked up the gold medal in the high jump and the silver medal in the long jump at the same meet — making it sound as easy as picking up vegetables at the supermarket.

And today, she is still the President of the Singapore Masters Athletics, the local governing body for athletes aged 35 and up.

These two great Singaporean women may no longer be running for Singapore today, but they're definitely an inspiration for all of us.

Top photo by Rachel Ng

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.