Singapore-based chef Christopher Kong only turns 33 this year, but his resume is ridiculously impressive.

The guy has cooked in two Michelin-starred restaurants -- NoMad in New York and Waku Ghin in Singapore -- as well as the eponymous Guy Savoy in Singapore, so named after its Michelin-starred chef.

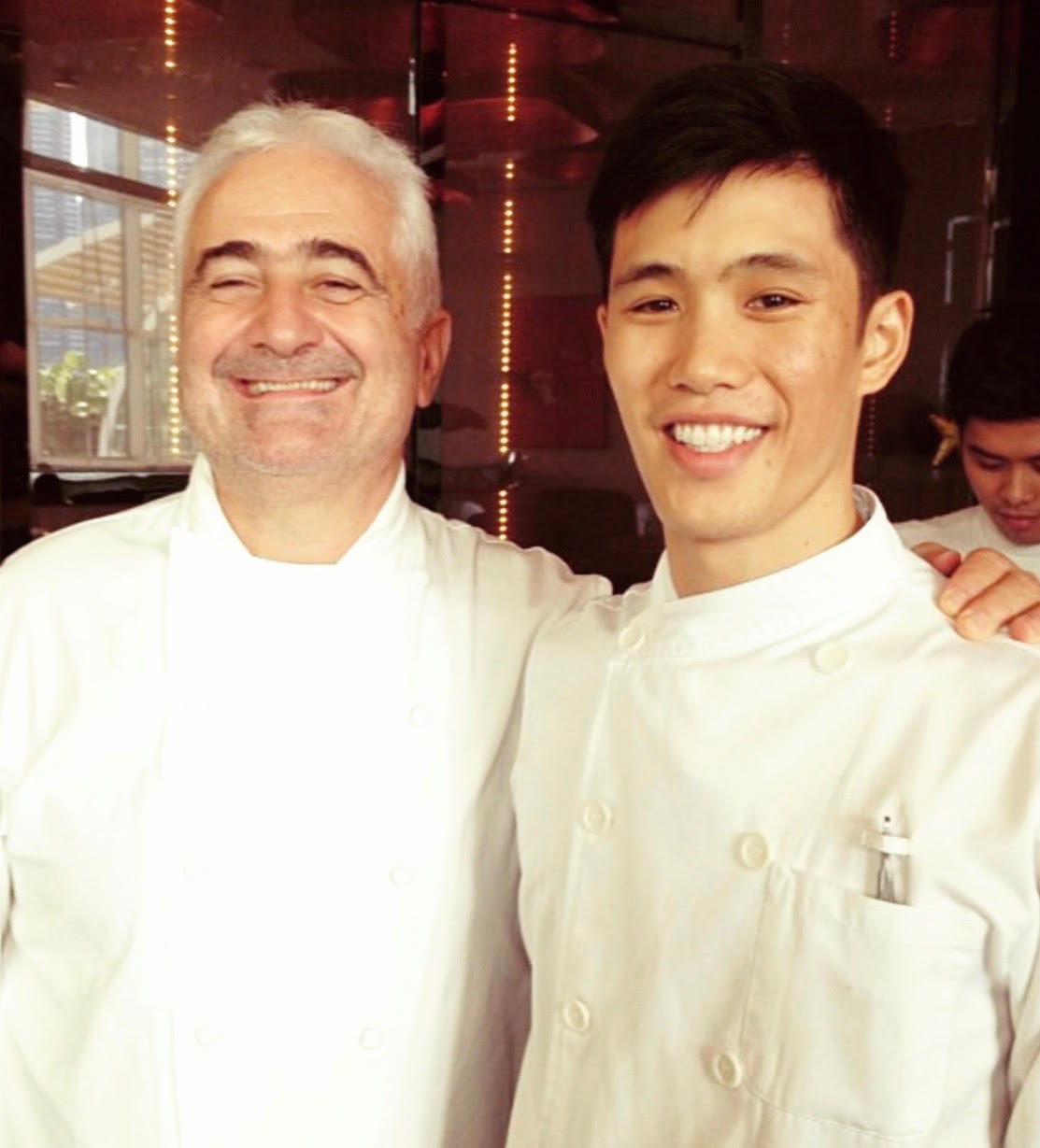

With Guy Savoy. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

With Guy Savoy. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

https://www.instagram.com/p/BXNq6m4DkY5/

With the management at NoMad. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

With the management at NoMad. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

At Waku Ghin. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

At Waku Ghin. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

Back to Southeast Asia after growing up in America

Accolades aside, perhaps one of the experiences that makes Kong's career in the fine-dining scene so unexpected was his previous stint at a tze char restaurant in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Back in 2010, when Kong was only 24 years old, he worked for three months in the sweaty, casual environment and lived in a dormitory with other staff.

Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

24-year-old Kong. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

24-year-old Kong. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

It was his first stop back in Southeast Asia, after growing up in Seattle, Washington.

"It was the first time I've ever cooked Asian food or been around that, so it was simply a new experience and definitely with new ingredients, but it was definitely an experience I would not trade."

Later on, Kong clarifies that it was not his first time cooking "Asian-Asian food", but rather, cooking the food in such a context.

Although the chef currently calls Singapore his home, the Asian American was actually born in San Francisco, and has lived in The States for much of his life.

Additionally, Kong's father is from Malaysia, while his Burma-born mother was raised in Thailand (the mixed heritage should explain his agreeable features).

With family. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

With family. Photo courtesy of Chris Kong

Both parents (and a brother) still reside in the U.S., but their extended family remains in Southeast Asia.

To make a better living

Although Kong's time at the tze char restaurant was fleeting, he comes across as sentimental when recounting his experience.

For the chef, it's about knowing the people, their backgrounds and culture, as well as why they were actually working there.

"Not everybody is necessarily there for the same reason you are," he added. "For some of them, it's a means to make a living and better lives for themselves and their family."

Describing it as a "tight-knit family/ community bond", Kong remembers it as a cohesive environment where everyone gets along and works together.

But these kitchen staff are around each other almost 24/7 -- besides being colleagues, most of them are also neighbours who live in the same set of dormitories, in close proximity to their workplace.

Four people share a room, living and working on the same property.

Given how big the country is, it's not difficult to see why the workers prefer to live on the premises, sending their salaries back to their families instead.

For most employees, contracts last for a year, after which they go. To where, Kong does not elaborate.

Of their transient nature, the chef gives a comment that is almost poignant: "You [referring to the other staff] don't necessary want to be there, but it's a better means than where you were from before."

On the other hand, Kong reveals that people who work in fine-dining want to be, and choose to be there.

Working at the bottom "as long as you can"

Besides the vastly different ambitions of its employees, the set-up of a Chinese kitchen and a French fine dining kitchen also varies greatly.

When asked which environment was more stressful, Kong replies that it's "different kind of structure altogether":

"In fine-dining, it's more about the details, it's about executing it, and every person has a role and understands what they need to do. And you're on timeline. And in that sense, it's a lot of stress, because everyday you're producing the best and it needs to be perfect."

In a tze char restaurant, however, it's a lot of prep work, and everyone has their own station as well.

Nonetheless, even with the stations, a Chinese kitchen is noticeably less structured, with each employee being well acquainted with several sections.

In terms of hierarchy, career progression in a tze char restaurant is rather stagnant in comparison to a French kitchen.

For the latter, a chef can work for six months at one station and move on to the next, slowly working their way up.

In a Chinese kitchen, one works at the bottom "as long as you can", or until one of the head chefs move on -- which is an "old school way of doing it", Kong admits.

Surprisingly, the hours in both environments are "pretty much the same" -- in short, really long hours.

One must, however, take into account that cooking at a tze char restaurant is significantly less comfortable, as temperatures are much hotter and there is no proper uniform (apparently the uniform works in their favour).

Furthermore, a tze char chef is exposed to so many things and in large quantities -- the restaurant cooks for hundreds of people, and it gets especially hectic on holidays like Chinese New Year, where everyone eats all at once.

Addressing the disparity, Kong acknowledges that "standards are a little bit different", as are the ingredients and the way they are handled.

As a result, tze char is a lot more flavourful and heavier on the palate, while fine-dining fare is a lot more curated.

But in case we have any doubt about the Chinese food, Kong supplements his previous statement: "But they [the chefs at the tze char restaurant] make the best of what they can with the situation and environment that they have."

Dearborn Supper Club

Kong's flat. Photo by Mandy How

Kong's flat. Photo by Mandy How

Photo by Mandy How

Photo by Mandy How

Now in Singapore, Kong runs a home restaurant, Dearborn Supper Club, out of his Chai Chee flat.

A relatively novel concept that is gaining popularity in Singapore, a home restaurant is where customers dine in a chef's home.

The menu is anything but a Singaporean supper of prata and mi goreng.

Instead, expect a six-course modern American dinner with "a few surprises", to quote Kong. To be more specific, it's "greens, grains, and sustainable seafood".

A meal at Dearborn costs S$138 per head, for a minimum booking of five to six in a party.

Photo by Mandy How

Photo by Mandy How

Most of the time, Kong keeps the dining sessions to twice a week on Fridays and Saturdays, and starts preparing for it as early as Wednesday.

The price is undeniably steep (compared to your average meal in Singapore), but Kong makes everything from scratch in his own kitchen, by himself.

A coconut dessert that Kong made for us. Photo by Mandy How

A coconut dessert that Kong made for us. Photo by Mandy How

Plants that Kong grows and uses in his dishes. Photo by Mandy How

Plants that Kong grows and uses in his dishes. Photo by Mandy How

Considering that the man has worked in several Michelin-starred kitchens, (very) well-heeled folks might even call it a steal.

Waste in fine-dining restaurants

However, some customers may balk at the fact that red meat is not on the menu, thanks to Kong's efforts at being environmentally friendly (meat production is believed to use a disproportionate amount of resources (e.g. farmland) and contribute greatly to greenhouse gas emissions, among other things).

In fact, the chef himself only eats beef once or twice a year during his travels, when he knows where the meat comes from (and we don't mean cows, smart alecks).

Photo by Mandy How

Photo by Mandy How

Furthermore, what most people may not know is the amount of food waste a fine-dining restaurant produces in the name of perfection.

Chefs are required to trim and shape the food to an ideal form, resulting in the excess being unused most of the time.

For the rest of the ingredients used at Dearborn, it's an ongoing process for Kong to source them locally and regionally.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BeCoAOyDX7p/

Although the home restaurant only started in November 2018 (i.e. four months ago), we heard in late January that slots for dinner are already fully booked till June.

Kong must be doing something right.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.