Aladdin, the classic tale of the boy and his magic lamp that yields a genie, was originally a story set in China.

This assertion and historical insight isn't particularly insane or a nefarious rewriting of history, but a going-back-to-the-roots premise of an article on South China Morning Post on Jan. 18, 2019.

A story set in China

According to the piece, Aladdin being remotely Chinese, or at the very least a story set in China, cannot be dismissed.

In the original story, Aladdin is born to a poor tailor in “the capital of one of China’s vast and wealthy kingdoms”. There was no mention that he was an orphan.

Hence, Aladdin and his princess might actually be Chinese.

This is also due to the first appearances of Aladdin's Chinese aspects being highlighted in book illustrations during the Victorian era, which is the period just before the 20th century.

When the craze for Chinoiserie was at its peak, Aladdin actually sports a Manchurian queue and Chinese slippers, and the architecture features distinctly Chinese pagodas, the SCMP piece wrote.

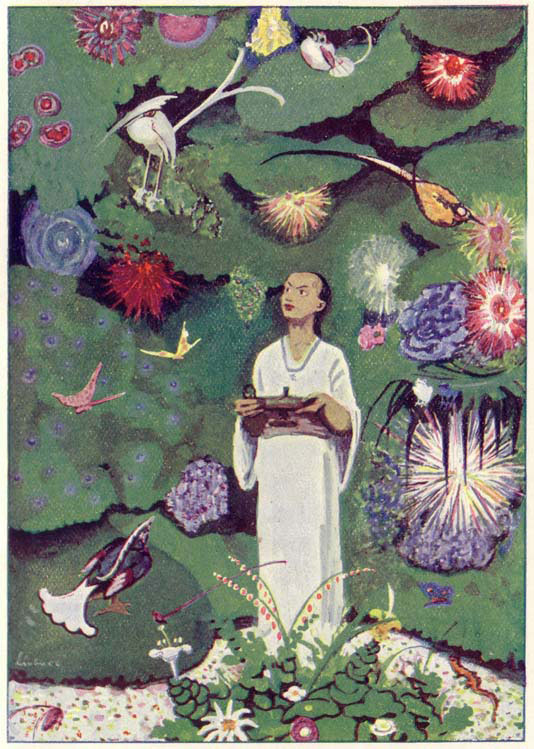

A 1912 illustration of Aladdin. Not very Arabic. (Aladdin in the Magic Garden, an illustration by Max Liebert from Ludwig Fulda's Aladin und die Wunderlampe)

A 1912 illustration of Aladdin. Not very Arabic. (Aladdin in the Magic Garden, an illustration by Max Liebert from Ludwig Fulda's Aladin und die Wunderlampe)

Chinoiserie was a decorative style in Western art, furniture, and architecture, especially in the 18th century, characterised by the use of Chinese motifs and techniques.

In mid-Victorian times in the late 1800s, there was a reaction against China (yes, even then) as its role in global trade was growing.

That was when Aladdin characters were sarcastically renamed after types of tea.

Such a change is not to just highlight a quirk of story adaptations.

It serves to show that historical events at that time had an impact on fictional tales.

What was the original version of Aladdin anyway?

What is difficult to dispute is that Aladdin was unlikely to have Arabic origins.

The story was first written down in the 18th century by Frenchman Antoine Galland.

It appeared in the first European version of The One Thousand and One Nights, the book of Middle Eastern folk tales also known as Arabian Nights.

Arabic manuscripts predating Galland’s by hundreds of years exist for most of the tales in One Thousand and One Nights.

But Aladdin, and the other popular stories about Sinbad and Ali Baba, were not found in the Arabic manuscripts.

Cross-pollinating of narratives

And this is where it gets complicated owing to Galland's claims.

Galland claimed he heard the Aladdin tale from a Syrian traveller, Hanna Diyab, whom he met in Paris.

This account was long thought to be Galland’s invention.

But after Diyab’s diaries were recently discovered in the Vatican Library, the veracity of Galland's claim appears to be more situated in fact.

Scholars have since debated about how much the story is a construction of Diyab’s, or was reinterpreted by Galland -- or both.

Modern interpretations

As an example of how slippery a story can get when it slides away from its roots, one has to look to the most popular retelling of Aladdin.

In books and films, Aladdin is often depicted as Middle Eastern.

One reason is because the Disney animated film of 1992 wrote out the Chinese origins completely.

Disney’s Aladdin, for all its Orientalism and wide-eyed splendour, is not based on Galland’s original text.

It is a product of the long tradition of movies based on One Thousand and One Nights, which starts with the 1924 silent film The Thief of Baghdad.

When Disney's Aladdin came out as an animation, the setting had to be changed from Baghdad to the fictional Agrabah, Arabia.

This was due to the ongoing first Gulf War in Iraq at that time that began in 1991, and the United States was still bombing Iraq when the animated movie appeared.

"Disney changed the setting to a fictional city to avoid awkward associations with the Baghdad of Saddam Hussein," it was explained in the SCMP piece by Arafat A. Razzaque, a PhD candidate of history and Middle Eastern studies at Harvard University.

No mention of Aladdin's ethnicity

Another layer of obfuscation is introduced when the characters are scrutinised for details.

The earliest story clearly stated the setting was China, but Aladdin’s ethnicity was never explicitly mentioned.

But the tale is given an overtly Middle Eastern flavour owing to the characters’ names, including the princess’, who is called Badr al-Budur (not Jasmine, as per Disney’s animated movie), the use of “sultan” instead of “emperor”, and references to Islamic practices, such as evening prayers.

More people should at least know about Aladdin's Chinese association

French-Syrian writer Yasmine Seale, whose new translation of the original tale was published in November 2018, has conceded by saying: “Aladdin is a shape-shifter, a paradox: it’s one of the most instantly familiar stories, and also one of the least known. It has survived by changing and reinventing itself -- the Disney film is just one in a long line of reincarnations that depart quite radically from the original story.”

“The text I have translated is the first written version, but even that is a slippery thing,” says Seale.

“As a story told by a Syrian to a Frenchman, each of whom was fascinated by the other’s culture, it can’t be pinned down to one language or literary tradition.”

Accounting for the mishmash of flavours and references, one way to read the original Aladdin is to accept that it was a product of cultural mash-ups at the time of crisscrossing trade routes and the morbid fascination for the unknown.

“The story might be set in China, but this is just a narrative strategy,” says Wen-chin Ouyang, professor of Arabic and Comparative Literature at SOAS University of London. “The tale is certainly more Islamic than Chinese."

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.