National Service in Singapore is a book recently published and released by World Scientific.

The book (which you can buy a copy of here) brings together a range of scholarly perspectives on National Service (NS) exploring its past, present and future.

Bernard Fook Weng Loo, an associate professor with RSIS's Military Studies Programme, contributed an essay titled "Goh Keng Swee and the Policy of Conscription" as a chapter in the book.

His essay discusses the historical backdrop as to how conscription came to be perceived as necessary for Singapore.

***

A section from Fook's essay is reproduced here:

By Bernard Fook Weng Loo

Clearly, the lack of popular support and the concerns over economic affordability were not sufficient to deter Singapore’s policy makers from adopting and implementing the policy of NS.

The reason for NS can be attributed to a sense of profound vulnerability from both external and internal sources in the eyes of Singapore’s policy makers.

NS was regarded as the only instrument that could provide Singapore with the capacity to address these profound vulnerabilities.

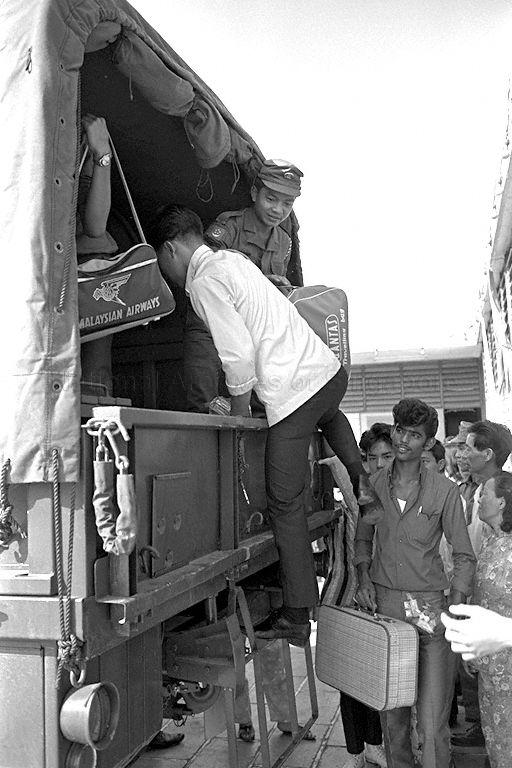

Youths reporting for NS in 1967. Photo via NAS.

Youths reporting for NS in 1967. Photo via NAS.

1960s threats to S'pore: Cold War, Konfrontasi & water supply

The Melian Dialogue, coming from Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War — where “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” — is the classic statement of the inherent vulnerabilities that plague small and weak countries.

Its perspective of how weak states must suffer the vicissitudes of their position reflected the dominant concerns of the first generation of Singaporean leaders.

Certainly it was an ever-present element in the world view of Goh Keng Swee and former Prime Minister Lee.

At the point of its independence, Singapore existed in a strategic environment that could be regarded as far from ideal. There were a number of potential externally derived challenges to Singapore’s existence.

The Cold War was the order of the day, and it manifested itself in Southeast Asia in the form of the so-called Vietnam War.

From the moment of independence, there was the history of Konfrontasi with Indonesia and threats from Malaysia to cut off the island’s water supply.

It is difficult to not conclude that the dominant image was one of potential trouble that could directly or indirectly affect the security of Singapore.

Another problem: the British were leaving

Up to 1970, British troops were stationed in Singapore to safeguard the island’s external defence, but the SAF had only two infantry battalions “for [her] protection in normal times.”

Infantry soldiers. Photo via NAS.

Infantry soldiers. Photo via NAS.

By itself, the SAF was clearly not in a position to do very much in terms of defending the island-state against external aggression.

However, when the British government announced on January 15, 1968, its plan to withdraw all British forces east of Suez by December 1971, the Singapore government had to begin plans to build up the SAF, since the island would no longer come under a British defence umbrella.

As a consequence, a central element in Singapore’s strategic culture was a pervasive discourse of vulnerability:

Where we are makes us an attractive target

There is a geostrategic element that underpins this strategic culture of vulnerability.

In contrast to its immediate neighbours, Singapore suffers from a natural geostrategic asymmetry — simply put, the island lacks geostrategic depth, stemming from its small geophysical size.

Tim Huxley also makes the point that the territorial waters of Singapore are completely surrounded by the territorial waters of Indonesia and Malaysia.

There was also a geopolitical element to this that pervades to this day.

Singapore’s position lies astride the trade routes connecting the Pacific and Indian oceans. This location places Singapore in a position to control maritime trade in Asia, and this makes the island a potentially attractive target.

Sans British, S'pore was "easily overrun by any neighbouring country within a radius of a thousand miles"

It is not that the Singapore government identified a specific country as a threat. Rather, the strategic problems for Singapore stemmed from the simple fact of its small size and the absence of a self-defence capability.

As Goh noted in Parliament on December 23, 1965,

"Our army is to be engaged in the defence of the country and our people against external aggression. This task we are unable to do today by ourselves. It is no use pretending that without the British military presence in Singapore today, the island cannot be easily overrun by any neighbouring country within a radius of a thousand miles..."

Later, on 13 March 1967, Goh reiterated this strategic narrative of inherent vulnerability: If you are in a completely vulnerable position anyone disposed to do so can hold you to ransom, and life for you will become very tiresome.

Another concern: domestic political instability making others want to intervene

There was also a subtle shift in the strategic narrative. Now, it was less the idea of another state invading simply because of Singapore’s weaknesses.

Rather, it was the idea that other states might want to intervene in the event that Singapore’s domestic political environment disintegrated into turmoil.

In the same speech, Goh noted,

"Small states are likely to be a great source of trouble in the world if they cannot look after themselves. If the management of their domestic affairs is so bad as to invite civil war and disorder, there is always the risk that larger states may be tempted to intervene ..."

In other words, there was a potential problem that derived from domestic political conditions.

The Malayan Communist Party

One source of domestic threat came from the communist threat emanating from the Malayan Communist Party (MCP).

Up to 1960, the MCP had perpetrated various acts of civil and political unrest and violence in an attempt to undermine the Singapore Government, with the ultimate aim of unseating the legitimately constituted authority.

Even after 1967, the MCP continued its campaign of terrorism and subversion.

2 rounds of riots

A second source of instability and insecurity emanated from communal politics. Indeed, communal politics was considered to be “the gravest threat” prior to independence.

There had already been two major incidents of communal violence in Singapore, the Maria Hertogh riots and the

1964 riots.

Protestors, Maria Hertogh riots (1950). Photo via NAS.

Protestors, Maria Hertogh riots (1950). Photo via NAS.

While these threats were largely domestic, they were nevertheless part of a symbiotic relationship with the external strategic environment.

"A Chinese island in a Malay sea"

A constant image that has run through Singapore’s strategic culture of vulnerability is that of a “Chinese island in a Malay sea”.

Being located within an essentially Malay and Muslim archipelago, Singapore was extremely mindful that “Chinese chauvinism” could adversely affect its relations with Malaysia and Indonesia and give both countries an excuse to intervene on behalf of the Malay-Muslim population in Singapore.

Similarly, “Malay chauvinism” represented a potential threat to Singapore in the form of Islamic fundamentalist movements.

Our sole direct security threat: Konfrontasi

It has to be noted that Indonesia was the only country to have directly threatened Singapore’s security by its initial refusal to recognise the Federation of Malaysia, which Singapore had joined from 1963 to 1965.

The then-Indonesian President Sukarno had launched a policy of Konfrontasi (Confrontation), which sought to mount a low-intensity challenge to the international legitimacy of the Malaysian Federation.

Bombing of MacDonald House, 1965. Photo via NAS.

Bombing of MacDonald House, 1965. Photo via NAS.

Singapore became a target of Indonesian sabotage and bombing, and there were apparently plans to even invade the island. Post-Konfrontasi throughout the 1970s, while relations between Singapore and Indonesia had stabilised, it is possible to argue that Singapore policy elites never completely lost any lingering concerns about potential threats arising out of Indonesia.

Nevertheless, it seems clear that between Indonesia and Malaysia, it was the latter that tended to occupy the attention of the policy elites, and Goh in particular.

M'sia held strategic levers over S'pore

To be fair, Malaysia never actually threatened military conflict with Singapore. Still, complications arose out of three problematic aspects to the Singapore-Malaysia relationship.

Malaysia, it seemed at the time, held all the vital strategic cards against Singapore.

The strategic levers that Malaysia apparently held over Singapore are a theme that runs through the memoirs of former Prime Minister Lee.

Refusal to vacate barracks

One such lever was the initial refusal of a Malaysian battalion stationed in Singapore to vacate its barracks and return to Malaysia.

Malaysia had refused to evacuate its troops stationed in Singapore and to release Singaporean troops then serving in Malaysian Army battalions. It took fairly intense British pressure to finally resolve this issue.

As Goh noted in Parliament on February 23, 1966:

“A disagreement of such a nature could have arisen in the way it did is symptomatic of a deeper malaise in the relations between the two governments on defence matters. This issue is but one of the many outstanding issues which had arisen between us.”

Alternatively, other Malaysian leaders less moderate than Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malaysian Prime Minister, might persuade “Brigadier Alsagoff (the commander of Malaysian forces stationed in Singapore at the time of separation) it was his patriotic duty to reverse separation.”

Throughout the 1970s, even though relations with Malaysia would never again reach such levels of crisis, the Singapore policy elites could not overcome “its sense of innate vulnerability.”

Several outstanding issues drove this concern over the relationship with Malaysia.

Separation from Malaysia

LKY speaking about separation on television. Photo via NAS.

LKY speaking about separation on television. Photo via NAS.

The first was the acrimonious manner in which Singapore and Malaysia became separate states and the subsequent strained relations across the Causeway — the connecting north-south bridge between Malaysia and Singapore across the Straits of Johor separating the two countries — resulted in a situation where Singapore’s policy makers could not rule out the possibility of a threat to the island-state emanating from Malaysia.

Malaysian politicians had felt that Kuala Lumpur had a natural right to ensure that Singapore would not undertake any policies prejudicial to Malaysian interests.

Conscription and expansion of SAF

One such policy perceived by Kuala Lumpur as prejudicial to its interests was the Singapore decision to rapidly expand the SAF through conscription.

Recruits being sent for NS in 1967. Photo via NAS.

Recruits being sent for NS in 1967. Photo via NAS.

To circumvent these Malaysian obstacles, the first NS call-ups were sent via post rather than through television broadcasts.

Given that the Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s decision to expel Singapore from the Federation was not

popular within Malaysia itself, there were concerns in Singapore about the possibility of the Malaysian Army invading Singapore to “take Singapore back into the Federation forcibly.”

Fear of coup

Another scenario revolved around the fear that:

“Malay ultras … in [Kuala Lumpur would] instigate a coup by the Malaysian forces in Singapore and reverse the independence we had acquired … If anything were to happen to Tunku Abdul Rahman, Tun Abdul Razak would become the Prime Minister and he could be made to reverse the Tunku’s decision by strong-minded ultra leaders.”

The water issue

Related to this issue of pressuring Singapore was the issue of water.

Not only was it physically much larger, but more importantly, Singapore’s vital water supplies came largely from Malaysia.

There were apparent threats from Malaysia to use Singapore’s dependence on Malaysia for its potable water supplies as a lever against Singapore adopting policies that would be “prejudicial to Malaysia’s interests.”

In his memoirs, former Prime Minister Lee referred to this scenario as “rash political acts” from Malaysian political elites and “random act of madness.”

Water was therefore the potential casus belli in Singapore’s relations with Malaysia.

This “concern” with Malaysia was, however, tempered by an admission that neither country was powerful enough to undertake military action of any kind in the early years of their existence.

If Malaysia was a major concern for Goh and his colleagues, it seems to have stemmed from the simple fact that Malaysia remains significantly larger, with a similarly larger population, than Singapore. As Goh noted in Parliament on February 23, 1966,

"Both Malaysia and Singapore do not have adequate defence forces at their command to deter aggression from their larger neighbours nor are they able successfully to fend any major assault mounted upon us. For some time until our defence forces are substantially increased, we have to depend on the military shield provided by our Commonwealth Allies...

... if the Governments of Singapore and Malaysia are unable to cooperate in their common defence, this must surely adversely affect the efficacy of the defence arrangements with Britain, Australia and New Zealand ... So cooperate we must, but this cooperation must be as between two sovereign States and not as between big brother and his satellite. It is therefore necessary that the Malaysian Government should revise its attitude towards the Singapore Government in defence matters."

Cooperation with Malaysia

There was, as such, an explicit recognition of the need to cooperate with Malaysia on strategic issues.

This cooperation was best manifested in the form of the Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA), a structure that bound the SAF with their Malaysian counterparts, along with Australian, British and New Zealander participation.

FPDA exercise, 2016. Photo via Mindef.

FPDA exercise, 2016. Photo via Mindef.

It is worth noting, however, that this was by no means a defence alliance or pact; rather the arrangement merely promised that the member countries would consult in the event of security problems emerging.

Bilateral cooperation between Singapore and Malaysia remained rudimentary, although given the fact that neither armed forces was well-developed at that point, this rudimentary cooperation throughout the 1970s was about all that either side could afford.

Top photo composite image, via NAS.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.