In 2017, the book Lancing Girls of a Happy World by Adeline Foo was published.

Foo's book traces the stories of Chinese migrant women who arrived in Singapore in the mid-1900s to work as professional dancers in the cabaret.

Lancing Girls of a Happy World is published by ethos books. You can get a copy here.

Background to cabaret in S'pore

The cabaret scene in Shanghai was booming in the 1930s, and the nightclub scene spilled over to Singapore as well.

During that time, work was scarce for female Chinese migrants. Being a cabaret girl, or "lancing girl" (a local mispronunciation of "dancing"), was an attractive choice as it paid well.

Here in Singapore, the world of cabaret thrived in three entertainment "worlds" — New World, Great World and Happy World.

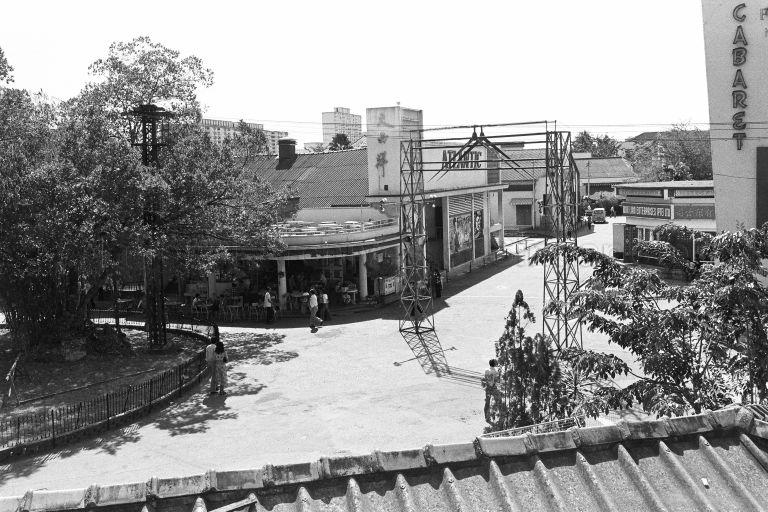

Great World Amusement Park. Photo via NAS.

Great World Amusement Park. Photo via NAS.

At the cabaret, a lancing girl's job was to dance with customers, and at a rate of one dance every three minutes. These girls were also hired to sit at a table and entertain customers with drinks.

Strictly speaking, these cabaret girls were not sex workers.

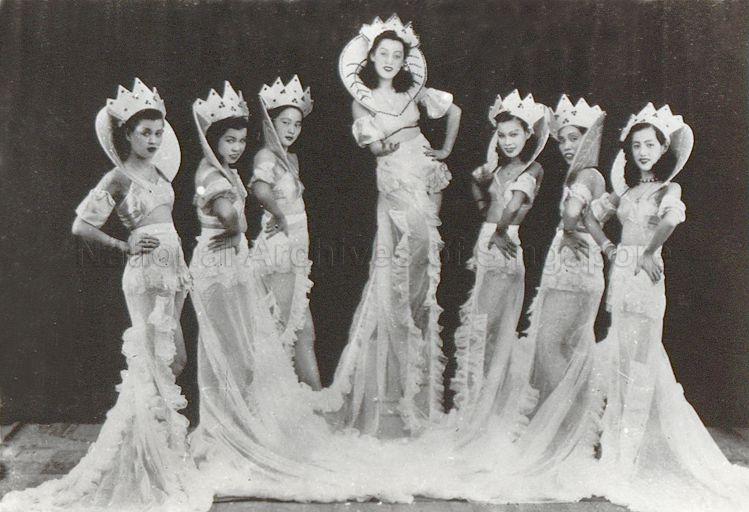

Cabaret girls at Great World (1945). Photo via NAS.

Cabaret girls at Great World (1945). Photo via NAS.

However, Foo's book highlights the seamier side of the industry, in which many cabaret girls ended up prostituting themselves. Some of them also got embroiled in the dangerous politics of secret societies.

Which brings us to this chapter from Lancing Girls of a Happy World, "Cabaret's seamier side", reproduced here:

Cabaret's seamier side

By Adeline Foo

Beneath all the glitz and attraction of the cabaret, the job was tough.

One brutally honest letter written by a former cabaret girl and published in Nanyang Siang Pau in 1976 shared that to survive, these women had to be extremely wary of their customers.

The job had many challenges

Men could be businessmen or secret society members, and offending the wrong ones would mean trouble.

To stay popular, girls were expected to look beautiful and well dressed.

They had to have a demure disposition, and be accommodating and caring. Girls had to learn to be sensitive to the needs of the customer, and adept at socialising.

When it came to money or gifts, the writer claimed that very few girls would be able to reject them. Some girls became mistresses (kept women) of their customers.

The writer ended her reflection with this woeful remark that “the ugly profession of the cabaret girls is an open secret; 卖淫 ‘mai yin’, to prostitute oneself, is a commonly accepted practice”.

Photo courtesy of Peter Lee.

Photo courtesy of Peter Lee.

This was something affirmed by my interview with a former male customer of the cabaret, who wished to remain anonymous.

He said: “It’s easy to find a girlfriend. You have money, you can do anything. But I learnt to be careful; I visited a clinic to witness an abortion being done to a female friend. It was a rude shock! I wasn’t prepared to be a father so young!”

While we should not come away with the impression that all cabaret women were “unchaste”, for want of a better word, the negative perception towards these women is difficult to shake off.

A former cabaret customer, who used to frequent the Happy World Cabaret five or six times a week, had this account to share,

“One of the regulations of the cabaret was that a girl could not refuse a dance. She could complain if the customer was abusive or difficult, but she couldn’t say no. These girls were allowed to be booked out when ‘mummies’ came into the picture. They controlled these girls, where they lived, what they ate. When the ‘mummies’ said the girls could leave the cabaret, usually near closing time, the girls would be booked out an hour before they left the cabaret, and this was when prostitution started. These ‘mummies’ would take a cut from the booking ($2 out of $12 an hour, this was the rate after the war). The standard of the cabaret dropped when more respectable girls left the cabaret because of this.”

Unwanted pregnancies, at-risk procedures

Most of these cabaret women believed they could take care of themselves on the job. But in my interviews, I learnt that it was easy to be led astray.

There were cabaret girls who got pregnant, but because they wanted to keep on dancing, they chose to abort their foetuses, putting their own lives at risk.

During an abortion, complications could arise, like getting lacerations in the womb or leaving with an incomplete septic abortion that could lead to severe infection.

There were legalised clinics to turn to; in the Geylang area, a “well-known” clinic managed by a Dr Harold Chan was quoted as one that women frequently turned to.

But sometimes, these girls turned to cheaper alternatives.

They would go to unlicensed medical workers or private midwives to assist them in terminating their pregnancies, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

When illegal abortions go wrong and cost lives

It was apparent that there was a veil of secrecy surrounding the subject of abortions, even to the extent of women shielding the identities of medical workers who conducted such procedures for them on the sly.

In an article by The Straits Times dated November 3, 1962, “Victim of An Abortionist Takes Secret to the Grave”, it was reported that complications from a botched operation led to 34-year-old Gertrude June Pinto contracting tetanus, which eventually killed her.

That was not her first operation by the same man, but the bar waitress had refused to reveal the name of the medical worker.

It was only known that the clandestine operation was done in the staff quarters of the General Hospital on New Bridge Road.

Another tragic case involved 21-year-old Lim Ai Choo, who had gone to a woman running a private maternity service in a garment shop on North Bridge Road.

According to an article in The Straits Times dated December 21, 1962, “Bar Girl Tells of An Abortionist, Then Dies”, she had paid $100 to have her abortion done, but problems arose, and she was rushed to Kandang Kerbau Maternity Hospital.

During the emergency operation to save her, she died on the operating table.

The (in)famous Rose Chan

Not all the stories were depressing.

There were entertaining ones, reflecting a time when people lived vivacious lives, and women in the entertainment scene seized the limelight brazenly to make a name for themselves.

One name that kept emerging was Rose Chan, a cabaret striptease dancer.

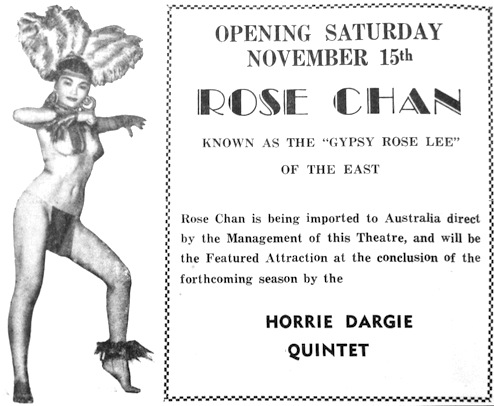

Photo via Jonathan Bollen

Photo via Jonathan Bollen

Everyone I spoke to for research remembered Chan, she was that famous. Her fame, or rather, infamy, came from being daring to strip naked.

But there were also women who blamed her for giving the cabaret profession a bad name.

Chan married at 16 to a much older man, but after her marriage failed, she turned to the cabaret for a job at Happy World.

She taught herself how to dance, and she was a quick learner.

She came in as runner-up in the All-Women’s Ballroom Dancing Championships in 1949. She was also runner-up in the Miss Singapore Beauty Contest in 1950.

The "Queen of Striptease"

Chan’s life had attracted a great deal of attention in the 1950s.

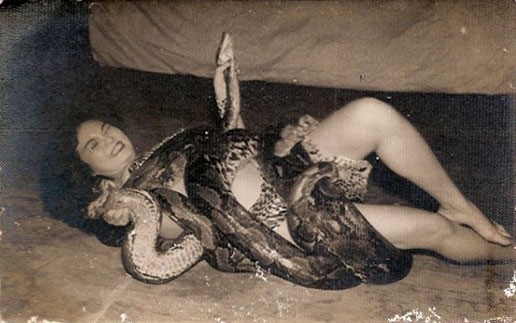

She was known as the Queen of Striptease for her sensational acts, which included a circus stunt known as the Python Act in which she wrestled with a python.

Photo via Jonathan Bollen

Photo via Jonathan Bollen

Chan named her two pythons Abdul and Boh Sia (meaning mute in Hokkien).

Why two? Chan’s act was very popular, often playing to a full house each night. Having two pythons ensured that the act could be alternated with a different python each night.

If Chan weren’t careful, she could be killed. On one occasion, spooked by the lighting of firecrackers before a performance, Abdul crushed Chan till she passed out.

Chan never assumed her pythons were docile pets after that incident.

Chan's ex-boyfriend opens up about her

By a rare stroke of luck, an editor friend helped me to secure an interview with the former boyfriend of Rose Chan.

Edward Khoo, 85, had known Chan for five years in the 1950s.

Khoo wistfully recalled that Chan was larger than life, feisty and full of spunk. She loved to dance, she loved music, and she never stood down a challenge.

“She was very popular in the cabaret. I had heard about her, and I wanted to meet her.”

He finally got the chance, and after he got to know her well, asked her to be his girlfriend.

“She agreed and I put her up in a house in 40F Lorong Melayu at Sims Avenue East. But we were never married as my parents objected to our relationship.”

Speaking about Chan for almost an hour brought up bittersweet memories. I could see Khoo’s face light up each time he mentioned the cabaret and his relationship with Chan.

In August 2008, a Singaporean theatre group The Theatre Practice staged the play "I Am Queen", which told the story of stripper Betty Yong, a character modelled on Chan.

Another production, a biopic of Chan’s life titled Chinese Rose, was to have been helmed by director Eric Khoo.

Actress Christy Yow was also cast as the lead, but for reasons unannounced, the project was called off by late 2009.

Going to the cabarets

Who were the men who frequented the cabarets?

Average salaried workers, the rich towkays who were managing directors of their own businesses, and soldiers and members of the British army or the navy.

Those with money would go about five to six times a week.

These men adored the cabaret girls for being good “talkers” and for the fun they offered.

“Besides dancing, there were the occasional sideshows. There would be hula-hula dancing and skits. The band would play in sets, giving the girls a break every 15 to 20 minutes,” said a former patron.

“What were really popular were the beauty contests. Voters got to cast their ballot for the ‘Best Dressed Girl’ or the ‘Cabaret Queen’. Bands that played in the cabarets were very good. Many were Filipino bands, and after dancing, people would have supper at the Chinese restaurants in the amusement park.”

Getting tangled up in gangs

Life in the cabaret also bordered on danger; fights and revenge killings were commonplace.

A former secret society leader shared,

“There are secret society members who hang out at the cabarets, looking for ‘girlfriends’.

We have many girls in the gang. We call them gang moll. Girls who tag along and meet our needs.

The prettiest ones are called the ang pai, the ‘red pack’. Many of them are dance hostesses, the gang leaders’ favourites. When a gang leader likes them, these girls get a bit more recognition than other girls. For protection and status. Other customers treat these girls with respect knowing that they have a backer who is a secret society leader.

We see our gang moll almost every night. But because I am a gang leader, there is always this fear, not only of the police or the government. You never know who’s going to betray you. You never know who’s going to walk up to you, even when you are in the cabaret dancing, and stick a knife through you.”

Working during the Japanese Occupation...

What about during the war, were the cabarets still running?

Yes, according to an account by a Mr Khoo Teng Soon, the Japanese allowed the amusements parks to carry on and life “went on almost as normal”. The girls had to serve Japanese soldiers as well.

“For girls in the cabaret, they were left without a choice when it came to receiving Japanese customers. To offend a military man would be stupid. If the Japanese visited the cabaret, it would be for two reasons. One, to look for spies, informants for the British. They would shine their torch and start looking for people. Two, if they made a play for the most beautiful girls, it’s only to ‘bring them out’."

... and even fighting the war in their own way

Another account from a former patron shared a lighter side of the war, through a “heroic” act pulled off by a cabaret girl.

“There was this cabaret girl called Lily Pang. She was really popular. She had some venereal disease but she couldn’t get treatment. All the Japanese men wanted her, but they didn’t know about her condition. She saw men from the air force, the navy, and the army; high ranking men between colonel and major rank. About two weeks later, the jeeps came one night filling the compound. The Japanese were screaming for Lily Pang, ‘Where’s the girl?!’ But she wasn’t there. She had disappeared. There was a big row. We heard all the Japanese men who took her out caught the disease. They were incapacitated for a long time. Out of action! That was how Lily Pang, a cabaret girl, fought the Japanese.”

Top photo composite image: Photo from NAS & Peter Lee.

Related story:

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.