Mothership and The Birthday Collective are in collaboration to share a selection of essays from the 2018 edition of The Birthday Book.

The Birthday Book (which you can buy here) is a collection of essays about Singapore by 53 authors from various walks of life. These essays reflect on the complexity of the future roads we must take, as individuals, and as a nation.

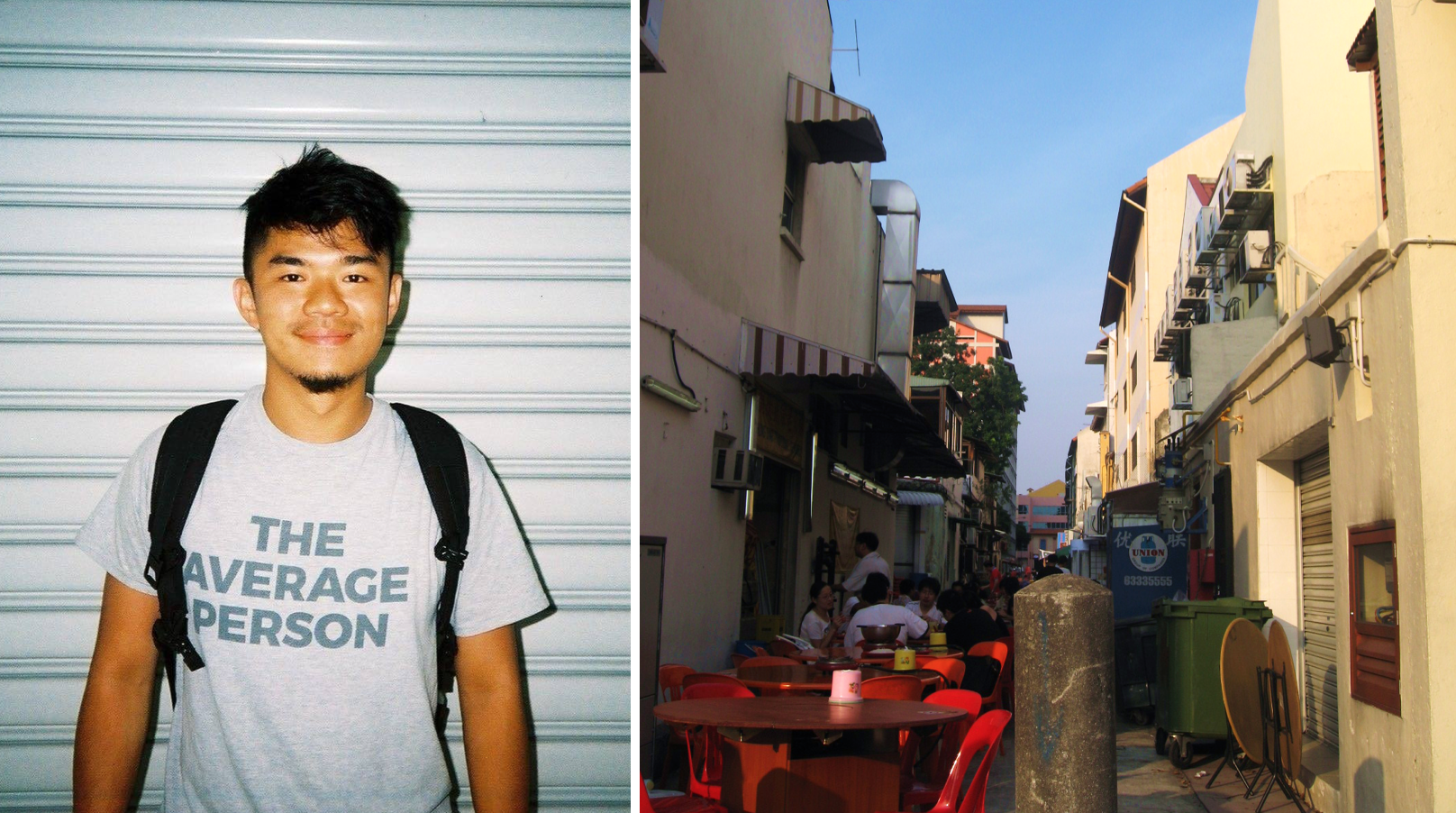

"Why We Should Care" is an essay contributed by Cai Yinzhou.

Cai runs Geylang and Dakota Adventures. He aims to develop ground-up models of advocacy for low-income communities and start conversations of equal power between migrant workers and Singaporeans.

Cai's essay is reproduced in full here:

***

By Cai Yinzhou

I’ve always lived in Geylang.

As a child, I wondered not about the roads we took, but why we had to avoid particular routes home.

I only realised many years later that my neighbours were a mix of characters ranging from regular families, to people engaged in gambling, prostitution and drug syndicates.

Left to free market forces towards the late 2000s, Geylang was a location of choice for migrant worker housing, which proliferated across a range of private apartments.

The neighbourhood of my childhood was a mix of shoebox condominiums for high wage expats and dilapidated, overcrowded apartments above shophouses for low-wage workers.

Lessons from the people of Geylang

Library? School? As a restless youth, my first love for my community came from discovering my preferred choice of study locale.

In the thirst for inspiration, beer gardens provided a safe and somehow appropriate space to synthesise and distill my thoughts— as I gazed and observed the dynamics across different groups.

Why do people drink? Individually, each held a story.

The lonely unmarried uncle lavishing gifts and sales commission to a beer girl, in hopes of a conversation or a touch of affection, even if from a stranger.

A beer lady hailing from a rural village in Vietnam, eventually marrying a 70 year old man, using her extended social mobility to earn more, and successfully sending her son to university.

The 20-year-old boy managing a small troupe of streetwalkers, who had lived without a fatherly figure and desperately wanted to help his ageing mother with her skyrocketing medical bills. With minimal education and friends, few things could earn him quick and relatively large sums of money like pimping could.

Watching all of them, I gradually realised that they were part of a delicate and diverse social equilibrium.

The messiness of the streets jived naturally with the dynamics between the groups, often unfortunately easily labelled as misfits in society.

Playing badminton with foreign-worker neighbours

I discovered my love for backalleys and their dwellers while playing badminton with my neighbours behind my house. Friendships blossomed; we shared hopes, dreams, family and views on things we cared for.

The largest contrast between us was our realities as 20-plus-year-old men.

I was a young Singaporean, at home in cosmopolitan Singapore, with an array of opportunities like other university graduates. They were low-wage construction workers, in a foreign place, separated from family for extended durations, with third-world standards of living, in search of a better future for the generation after them.

In comparison with my peers, the diversity in my neighbourhood entailed interesting conversations and new perspectives.

To be honest, it would have been challenging to "love thy neighbour” if I only had known them for their labels. But underneath the easy labels, the place of my childhood is teeming with living networks and informal relationships.

These aren’t obvious to everyone, unfortunately.

Geylang and state control

After the 2013 Little India riot, Parliament’s Committee of Inquiry referred to Geylang as a “keg of gunpowder ready to explode”.

They compared statistics of crime in Geylang to Little India to justify why measures targeted at preventing a repeat of the riot were necessary in both neighbourhoods.

The rectangle of Geylang that was designated as a liquor control zone has two important characteristics:

- Salvation and sin: It contains the only legal red light district in Singapore, but also the highest concentration of religious institutions, including some buildings housing as many as six religious groups.

- Private lives: There is no public housing within the rectangle, with the majority of residents living in apartments and shophouses. The area is also home to the highest concentration of new condominiums since 2012.

This rectangle has experienced numerous changes in the name of development: increased enforcement, surveillance and lighting up of all backalleys, even the integration of smart lampposts in the near future.

Geylang as a nuanced space

I wonder sometimes how to reconcile these realities: the place that needs scientific security measures, and the “other Geylang” where I grew up.

A simplistic story is that Geylang is a sacrificial lamb for the rest of Singapore to be safe.

However, the real story is much more nuanced, full of conundrums and contradictions once we dig into the details of the community and the interactions within it.

And each story affects the other.

Unintended consequences of state control

In the short term, the post-riot measures have consolidated low-wage worker populations in purpose-built dormitories.

Recreation centres meet all their needs without having them congregate in social nodes like Geylang and Little India.

However, the unintended consequences of clamping down on vice has been to relegate prostitution activities to jungle and HDB brothels, online spaces and massage parlours, creating a cat-and-mouse game for enforcement agencies.

For playing badminton in the backalleys, we were even raided by the police.

The broad policy of clamping down on crime was both rational and well-intentioned, but has caused unintended consequences by disrupting the community’s delicate equilibrium.

We do not need to travel for new perspectives

Geylang always reminds me that we don’t always need travel to show us new culture and perspectives.

Places like Geylang are teeming with people bringing new insights to our society every day, their determination and sacrifices providing valuable lessons for our young.

I know I am not the only one constantly inspired by their generosity, despite how little they have: seen in small kindnesses like going out of their way to hold umbrellas in the rain, returning lost wallets, and more dramatic single-handed rescues of babies while scaling heights.

[related_story]

So, why should we should care?

So why do I care about Geylang and the roads I’ve taken in it? Why should all of us care?

The strength of Singapore lies in our diversity — since our inception, early migrants came with the same sense of purpose, forming mutual help groups like clans and associations that contributed actively to our early nation building.

They formed communities, built public infrastructure like schools and hospitals, kept their eyes on the possibilities for a better future.

They were the first proponents of values like meritocracy and hard work, earning the right to call Singapore home regardless of wage or class.

Geylang, like Singapore, is an ecosystem

In contrast, today’s segregation of low-wage workers, by built design or unequal social mobility, will continue perpetuating divides within communities — the necessary jobs these workers do shunned by local populations, the disinterest in mixing persisting while we ignore our mutual interdependence.

Geylang, like Singapore, is ultimately an ecosystem — a community of organisms with interdependent relationships. We cannot forget the need for reciprocal interactions, and to value one another beyond economic transactions.

This is why, we should care.

Top photo via Cai Yinzhou's Facebook and Wikimedia commons

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.