Ho Kwon Ping is a man highly sought-after for his opinions.

He is almost constantly being invited to conferences, organisations and educational institutes to give talks, sit on panels and get quizzed about geopolitical shifts, international relations, leadership, the business world, you name it.

He was even invited to tea (yes, that tea), and almost found himself being fielded on the People's Action Party's slate of candidates in the 1984 General Election.

Certainly, the person Ho is is fascinatingly unique — ex-journalist, jailed and barred from travelling to the U.S. and also incarcerated under Singapore's Internal Security Act, founder of the Banyan Tree resort empire, and founding chairman of the Singapore Management University.

It is perhaps that, and what he believes to be his lifelong interest in politics and what's going on all over the world, that makes him so knowledgeable and opinionated about pretty much everything (he's still waiting to watch "Crazy Rich Asians" with his wife Claire Chiang so he can decide on his stance regarding that as well).

His secret: Netflix, apparently.

But who is Ho Kwon Ping, the person? We know from his public speeches and witty, self-effacing responses in forums and panel discussions that he doesn't take himself too seriously.In our latest conversation with him last week, though, we learned that he is all the above, but also in equal parts romantic, sentimental and nostalgic. He is obsessive about family, for instance, despite all the travelling he has done and the years he has spent alone overseas — or perhaps that itself is the very reason he feels this way now.

We're sitting with him in his living room, with tall windows all around the standalone structure in his home. Glancing around, we wondered why the trees in the vicinity were palms and other smaller varieties, until Ho turned our attention to beyond the windowed wall behind the couch we were seated on — three Banyan trees overlapped one another, which he and Chiang planted for each of their children.

It is those that flank Ho's decades-old home — what is arguably the mother of the Banyan Tree resorts Ho started in so many different countries all over (including Austria, Cuba, Mexico, Seychelles and Mauritius).

But we digress.Why are we meeting him a third time in four years? Not because we hope to catch him with his pants down on a thorny issue (that's already been done by someone else ?), or to check out his house, but because of his latest book, Asking Why — a compilation of speeches, writing and essays piled behind a 48-page-short autobiography he wrote — released some months ago.

So blasé he was about it, though, that he decided against holding a fancy book launch or having it played up with too much fanfare — although a series of recent talks and interviews he has done have propelled him (more precisely, his views) back into the public eye.

But we wanted to get Ho away from all that. We turned instead, to his personal life, family and introspection for what he's started calling the last third of his life (he's 66 now, and plans to live "at least till 99"). And that's what led us to what we started with, in a completely not-morbid way — the remainder of his life.

[related_story]

The last 1/3

Photo by Ilene Fong

Photo by Ilene Fong

In the conclusion of his biography, Ho wrote that he looks forward to the final one-third of his life "with excitement, though tempered by wisdom and adversities".

Has he any plans for this final burst of fire? Being a bit less headstrong and opinionated, to begin with — to avoid trouble, he says with a chuckle. He also hopes to continue having an interest in the world, but ultimately, apart from the certainty of grandfatherhood — he will be a granddad of three by the end of this year — he admits he "really (doesn't) know".

"It's good not to know too much", he concludes.

What about how being a granddad has changed him, we ask — back in 2015, Ho told Tatler that one of his life's highlights was the birth of his first and only grandson so far; that little boy is now three.

"The other perspective, I suppose, is you do begin to see your own mortality. But at the same time it makes you much more sanguine about aging, because you do realise there's a really much greater awareness about the cycle of life."

Discovering his dad's deep, unspoken love for him

Ho Rih Hwa. Source: Singapore Management University website.

Ho Rih Hwa. Source: Singapore Management University website.

And that's the moment the door into Ho's past starts to inch open — he reveals to us that he had just (the night before meeting us) finished reading his father's personal diaries for the first time, having found them after recently clearing his late parents' old home.

Ho's dad is the late Ho Rih Hwa, and those of you from Singapore Management University (SMU) would likely recognise his name, from the university's Ho Rih Hwa Leadership in Asia Public Lecture Series.

Like Ho, his dad led a rich and eclectic life — he was a businessman, and refused to accept a salary when he was appointed Singapore's Ambassador to several countries such as Thailand, Belgium and Germany.

In his diaries, Ho was moved to discover that his father had kept every aerogramme (a lightweight, self-sealing letter card. Don't worry, we've never seen or heard of one before either) Ho sent him from his years spent studying, living and working overseas.

"I read stuff that I had written over 40 years ago to him — in aerogrammes and birthday greetings — and they were very warm and emotional letters which I'm glad that at that time he read all the emotional things I said about him...

Ho describes his late father as "very kind and very close" to him, but not outwardly or physically emotional.

"And unfortunately... he had his first stroke when I was still in Hong Kong, and I had already by that time written to him before he had his stroke that I was thinking of leaving to come home to the family business.

It was very touching for me (to read) how happy he was that I was going to come home finally and this and that, and then he had his stroke. I came back, and then we worked together for another 10-over years, but over that period of time he was already beginning to deteriorate and he had quite a number of mini-strokes before he began to lapse into a coma for a number of years, so he had a very long dragged-out illness.

So I do regret — that's one of my biggest regrets, that we weren't able to really be father and son in a much more... collegial and best-friend sort of way."

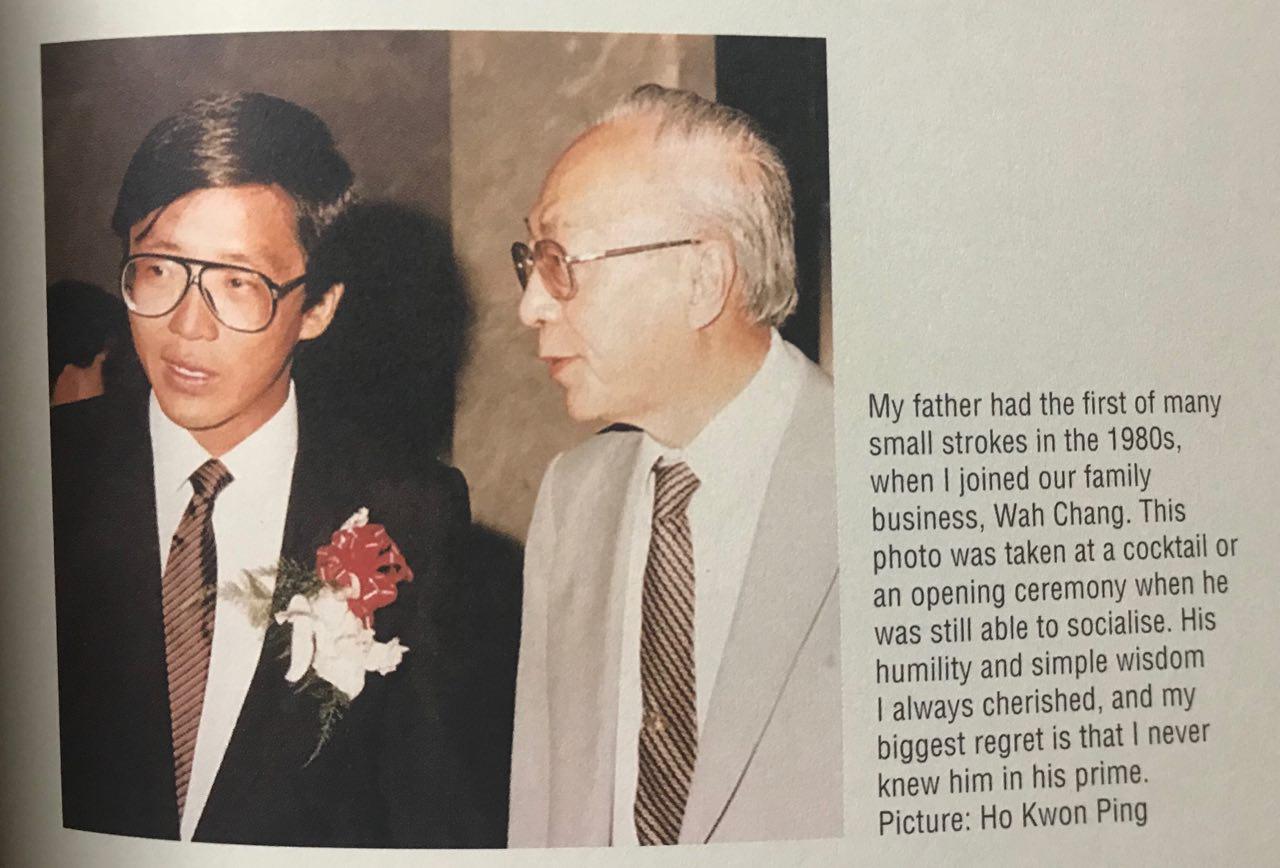

In this caption from Asking Why, Ho writes that his biggest regret in life is not getting to know his father better in his prime. (Photo of page from Asking Why)

In this caption from Asking Why, Ho writes that his biggest regret in life is not getting to know his father better in his prime. (Photo of page from Asking Why)

Ho shares that he was able to immerse himself in his late father's life by reflecting upon what he read and drawing parallels to his own life:

"I noticed his notations in his diaries — about my being born, and then my son being born, his comment about his own health at a certain age, and my health, his comment about me joining the business.

So I would look at what he has written and his life, at the age which he commented, and then compare to my own life and my own age, and you began to have an understanding of that cycle of life. I am now at a certain age of my father where certain things happen... It just gives you a greater appreciation of the value of life."

A suffering that moved LKY to sign an advance medical directive

Another poignant moment in our conversation came when Ho talked about his late father's affliction by a series of debilitating strokes in his later years.

In returning from Hong Kong to Singapore to join his father's business, Ho witnessed the aftermath of his father's first stroke, and his declining health and quality of life over what would stretch out over almost two decades. Ho's father would eventually slip into a coma following a massive stroke in 1993, and eventually died age 81 almost six years later, in 1998.

As the late Lee Kuan Yew was friendly with the Hos, Ho shared that he had gone to visit Ho's family when his father died.

"I understand from his daughter (Lee Wei Ling), not from him, that after seeing him, he also made an advance medical directive (AMD), that if it ever happened to him, he didn't want to be saved. Because he was quite moved by how life can be like if you're comatose, and do you really want to live on?"

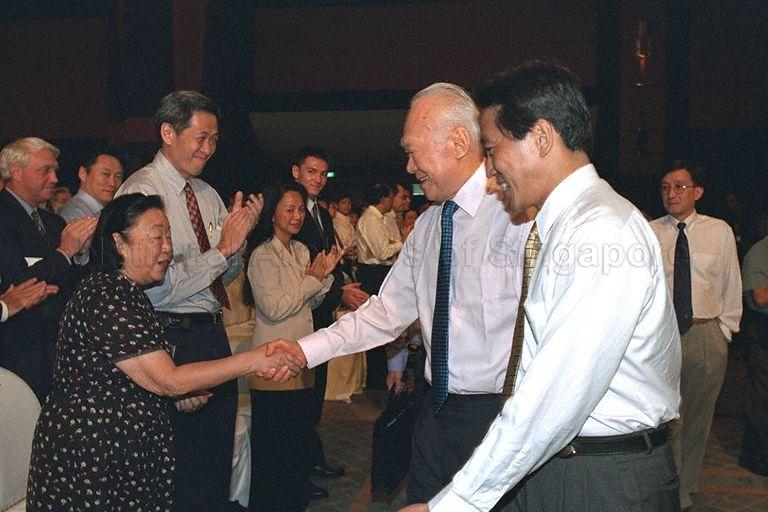

Source: Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts, National Archives Online.

Source: Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts, National Archives Online.

Ho also says he will always remember Lee's kindness towards his family, when he agreed to give the inaugural Ho Rih Hwa lecture. That move would give it much more prominence than other long-running and more distinguished lecture series in Singapore, which most recently featured Malaysian Prime Minister-in-waiting Anwar Ibrahim:

A final round of saké with his mum

But when we asked Ho if he remembers his last moments with his parents, it is a distinct memory of the final evening and conversation he would ever spend with his mother that he shares first.

Source: Esplanade website.

Source: Esplanade website.

Ho's mum is Li Lienfung, a well-known bilingual columnist for both The Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao, and an award-winning bilingual playwright and writer. She died at the age of 88, seven years ago.

Ho shares that in Li's final years, he would go out every Wednesday night to have dinner, one-on-one, with her.

And as both of them enjoyed drinking, they often drank together too.

Source: Esplanade website.

Source: Esplanade website.

Here's what he told us about his final night and conversations with his mum:

"It was on a Friday. And for some odd reason, we talked about death. And we had finished two bottles of sake each (We double checked — the bottles were small). We had a really good time and we were talking about death... and without morbidity at all.

I remembered very well that she had said there is never a good time to go, there's only a good way to go. And we're toasting each other, and I toasted her and say, 'may you live long', and she said, 'Yeah, but you know you're going to die too', and I said 'you are going to die too, just live life with meaning' and all that... and she said, there's only a good way to go, not a good time to go.

Because she remembered that my father did not have a good way of going...

On the Monday after that, my mother had a massive aneurysm. We rushed her to the hospital; three days later, she died. So I feel blessed in the sense that we had a great conversation about death and life, and all these kinds of stuff that two drunken people have. And then she just died like that."

Advice for young people

Reflecting on the suddenness of death, Ho told us about the eulogy he delivered at SMU's memorial service for the late former president S R Nathan.

Source: Institute of Policy Studies Flickr.

Source: Institute of Policy Studies Flickr.

There, as well as in speaking to us, Ho exhorted young people "never to put off seeing your loved ones, because you never know when it might be the last time".

He tells us about his and his wife's last visit to Nathan at his home — they chatted with him for over two hours, enjoying Mrs Nathan's samosas.

Little did Ho know, though, that it would be the last time he would get to see the late former president alive.

Source: Institute of Policy Studies Facebook.

Source: Institute of Policy Studies Facebook.

He also would discover later that he would have the poignant honour of being the recipient of Nathan's last-ever written thank-you note.

As a habit, the late Nathan would always send handwritten letters of thanks to his friends and volunteers.

In his note to Ho, he wrote:

"You indeed overwhelmed us with your visit and show of concern for us and our health...

Meanwhile, thank you and Claire for all the kindness you have showered on me, all these years. If not for you, I do not think I could have an active working life.

I particularly enjoy watching Monisha (Nathan's granddaughter) in conversation with you."

It was found sealed on his table by his family, who passed it on to Ho. Nathan had sadly slipped into a coma before being able to send it out.

At this point, he goes into naggy-uncle mode, reiterating what would be the first of two lessons he has for young people:

"All the people that you know — whether it's your parents, your grandparents, your uncles, your aunties, your teachers, you really don't know when is the last time you might see them. Take the opportunity to do so. We don't always live up to it... You never know."

Why is Ho Kwon Ping, Ho Kwon Ping?

So why does Ho Kwon Ping keep asking why?

Ho explains that "asking why" is a habit he actively encourages in his children and his grandchild.

"If you start at a young age of asking why of everything around you, starting from school days, that innate curiosity for knowing answers, not accepting answers that are just standard, asking questions, and discovering the answers, I think it's the start of a creative journey".

Ho shares at this point that, in the wake of the launch of Asking Why, somebody wrote to him and suggested that his next book should be "why not?" He agrees, adding that "why not?" is certainly the next question one should ask, as "it opens the world to you to create the world that you want to do".

"I think the worst thing you can do is to sleepwalk through life, wake up at the age of 66, 67 and then realise that gee, you know, what did I do?

It's not did I become rich, did I become famous, but did I really live a life of purpose, of excitement, of meaning for myself — or did I just sleepwalk through it, kind of not knowing what I wanted to do, and then sort of wake up one day and (realise) you haven't done anything with your life?

That's particularly easy to do in an affluent society."

If there is just one conclusion we can draw from all this, it's absolutely that Ho did not sleepwalk through life.

As he concludes in his book,

"I don't believe in artificial milestones, but after my 65th birthday, I stepped back to reflect a bit more than usual. For my parents' generation, this milestone would have represented the start of the twilight years, the slow retiring from not only business but also public activities, and the dimming of the light.

For my generation, this milestone represents the start of the final one-third of our lives, when experience, wisdom and grace can be all brought together to enable final acts of purpose and meaning."

Our chat overruns, and Ho excuses himself, heads off to Chiang's birthday lunch and leaves us to see ourselves out.

For indeed, when you have one-third of your life left to accomplish "final acts of purpose and meaning", every minute counts.

Read our other Ho Kwon Ping interviews:

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.