Hawker centres in Singapore run by not-for-profit social enterprises are getting massive bad press.

Where did bad press come from?

Foodie-critic-consultant KF Seetoh crystallised the argument against social enterprise hawker centres and highlighted their shortcomings in an Aug. 28 article, Not Social Enterprise Hawker Centres.

What are hawker centres run by private social enterprises?

Hawker centres run by private social enterprises are meant to theoretically marry the best of both worlds: Keep food affordable for the masses and available a lot of times, while operating according to free market competition rules with little government oversight.

In other words, it abides by a planned laissez-faire approach: Pricing mechanisms are free from government intervention, but social obligations have to be discharged, regardless.

As part of their social welfare goal, some of the stalls in these hawker centres are required to provide an affordable option for diners -- food at a max price of S$2.80, for example.

To date, there are 13 hawker centres and markets run by social enterprises, including Fei Siong, NTUC Foodfare, Timbre, Koufu, and Kopitiam.

But one unintended outcome is the tendency for prices to be pushed upwards -- because, hey, free market competition and there's no such thing as cost absorption.

Why were private social enterprise hawker centres created?

Originally, hawker centres were set up and run by the National Environment Agency (NEA).

Over the years, rising food costs and higher costs of living prompted the government to announce in 2011 the decision to build 10 more hawker centres by 2021 as a way to provide affordable food for Singaporeans.

In November 2011, a Public Consultation Panel on Hawker Centres was formed to provide ideas on how new hawker centres can continue to meet the needs of the people.

The panel submitted several recommendations, including the proposal to have hawker centres "operated on a not-for-profit basis by social enterprises or cooperatives".

The reasons provided for this particular management model were:

- Hawker centres should benefit the community

- To provide employment opportunities for the low-income or under-privileged.

The Ministry of Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) accepted most of the recommendations.

MEWR welcomed the proposal to let hawker centres be run by non-profit organisations, but added that "NEA retains oversight of hawker centre management".

Senior Minister of State for the Environment and Water Resources Amy Khor added that private social enterprises will have "greater flexibility and space to experiment with new ideas and processes".

Fast forward to 2018: NEA has 13 hawker centres and markets run by social enterprises, including Fei Siong, NTUC Foodfare, Timbre, Koufu, and Kopitiam.

Stalls at Ci Yuan Hawker Centre run by Fei Siong social enterprise, for instance, need to offer two dishes with a price ceiling of S$2.80.

Why are costs at social enterprise hawker centres going up?

Miscellaneous extra charges are factored in on top of the regular rent social enterprise hawkers have to pay.

These charges can add up causing the total operational costs to balloon to twice the stall rental costs.

One hawker told Channel News Asia that NEA-operated hawker centres have a "flat rate" and only "one layer" of costs, whereas social enterprise hawker centres have many other costs factored in.

According to this hawker, his monthly stall rental at a social enterprise hawker centre is S$2,000, but because of the accumulated service fees, he ends up paying close to S$4,000.

In comparison, hawkers at Maxwell Hawker Centre -- located in a prime location in the Central Business District -- pay about S$2,000 to S$3,000 per month in total.

On NEA's website, you can take a look at the monthly successful tenderers.

Some of the monthly stall rentals start from S$8.

The procedure for tendering, a transparent enough process, can be found here.

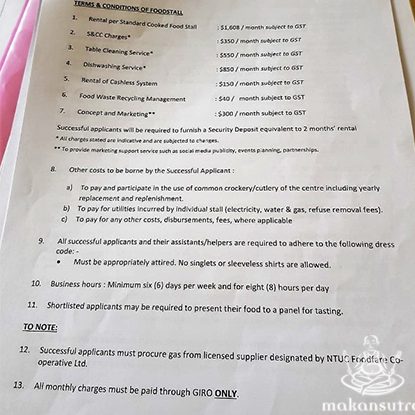

What are some of the charges incurred by hawkers imposed by the social enterprise?

According to Seetoh, these extra charges include:

- Coin-changing service, which can cost S$50

- Social enterprise taking a percentage of the hawker's overall takings each month instead of basic rent, depending on which one is higher

- Charges for table cleaning, crockery washing, collection and return

- A miscellaneous S$600 compulsory monthly fee for the social enterprise to conduct spot checks on hawkers' food quality and operation, which the social enterprise Fei Siong claims is optional

- Levying financial penalty charges for closures -- similar to how a food court is operated as hawkers are expected to open eight to 12 hours a day (minus preparation time)

- Renting the cashless payment system

- Paying for food waste recycling

- Contributing towards concept and marketing fees

- Payment for mandatory service and conservancy

- Utilities

Bear in mind that these are on top of the cost of renting the stall.

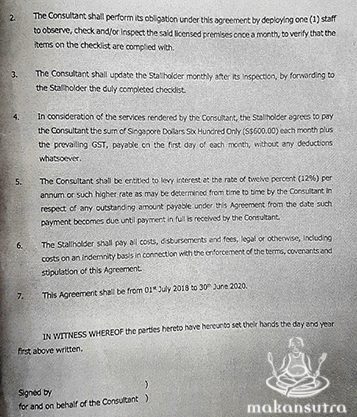

To cap it off, stall owners are levied an interest of 12 percent on outstanding payments.

Contact agreement posted by Seetoh. It states that the stallholder has to pay the operator S$600 every month. Via Makansutra.

Contact agreement posted by Seetoh. It states that the stallholder has to pay the operator S$600 every month. Via Makansutra.

Extra charges that are to be paid by stallholders, including stall rental. Via Makansutra.

Extra charges that are to be paid by stallholders, including stall rental. Via Makansutra.

How has the determining of rental rates changed?

NEA uses a tender bidding system to determine rental rates.

On the other hand, social enterprise operators are free to set their own rental rates.

Seen another way, social enterprise operators have taken over NEA's role, and the expectation is for social enterprise operators to inject ideas into making the hawker trade viable and attractive, as they have more wiggle room for experimentation compared to a government entity.

According to The Straits Times, NEA does not charge full market rate for stall rental if the highest bid during the tender period is below market value.

NEA has said before that it does not intervene in the prices of food set by hawkers.

However, it stressed that it has "put in place measures to ensure that the managing agents keep food prices and stall rental (and other operating costs) affordable" for social enterprise hawker centres.

It did not elaborate on those measures.

What is the tension in fulfilling various objectives?

Many of these social enterprise hawker centres, such as Ci Yuan Hawker Centre in Hougang and Bukit Panjang Hawker Centre, are located in neighbourhood areas, which do not see much footfall during the day, making it very difficult for these hawkers to recoup operational costs.

In a 2015 CNA interview, the co-owner of a food stall at New Upper Changi Road run by social enterprise NTUC Foodfare, captured the problem first-hand: "The cost is times two, so we have to manage the price and can't increase them... It’s difficult to manage, but prices are still affordable for customers to eat."

This has resulted in irony.

Privately-owned coffee shops and NEA-run hawker centres a lot of times end up being able to offer cheaper operational costs, which according to Seetoh, are "more 'social enterprise' in practice".

How badly did the first social enterprise hawker centre turn out?

The first social enterprise hawker centre bombed.

And its operational costs was just a symptom of the root problem faced by social enterprise hawker centres.

Kampung@Simpang Bedok officially opened in February 2013, but closed nine months later due to its lacklustre location, stiff competition from surrounding eateries, and lack of funding from investors.

The hawker centre was set up by Best of Asia, consisting of a group of investors hailing from a range of industries.

Kampung@Simpang Bedok. Via Wackydup.com.

Kampung@Simpang Bedok. Via Wackydup.com.

Full rental for stalls at Kampung@Simpang Bedok was about S$3,000.

Even so, Best of Asia offered stall applicants the option of paying subsidised rental, offering installment plans, or even paying the stall owners a salary until they could afford to pay rent.

Best in Asia lost S$1 million in total.

The founder of fashion label 77th Street, Elim Chew, told Today, in response to the closure of Kampung@Simpang Bedok:

"It takes a lot to get it to work, because you are a business but at the same time you are helping people. How (then) do you put it all together?”

Many of these social enterprise hawker centres are now located in heartland areas, which do not see as much footfall in the day.

They rely a lot on patrons who visit for dinner and on the weekends.

Public goods cannot be supplied by private organisations

Unfortunately, private social enterprise hawker centres have too many objectives to meet.

Admittedly, these private organisations are nimbler and more flexible when it comes to implementing new ideas, such as the cashless mobile app system or the "incubator programme" at Yishun Park Hawker Centre, which is operated by Timbre.

Yishun Park Hawker Centre. Via YouTube.

Yishun Park Hawker Centre. Via YouTube.

However, ST reported earlier in the year that the Yishun Park hawkers were unhappy with the mobile app that offers discounts to customers, as it ends up eating into the hawkers' revenue.

The hawkers also told the newspaper that the rent at Yishun Park Hawker Centre was higher than other hawker centres elsewhere.

This ongoing experiment of taking hawker centres out of NEA's hands has shown that private social enterprises at the moment cannot run the show as compellingly, because they lack the wherewithal of the state to partially subsidise the running of hawker centres for the good of the general public.

In the long run, if all hawker centres are managed according to the private social enterprise model, then they might stand a chance as the playing field is level.

But when that day comes, the texture of hawker food might have changed drastically, especially in comparison to what can be found in Malaysia, where flavours and quality retain the classic old world charm.

[related_story]

Yes, in theory, the government's way of maintaining low hawker prices is by increasing the supply of hawker centres.

But if private social enterprise organisations cannot keep operational costs low enough, hawkers cannot provide cheap food, while contending with exorbitant operating costs.

The question now is: Is it too late to transfer hawker centres back into the hands of NEA for it to run the whole thing?

Or is there more that needs to be done to fine tune the outcome to meet the lofty objectives first laid out for private social enterprise hawker centres to meet?

It is no wonder hardly anyone wants to be a hawker these days.

Even if hawker culture one day becomes a Unesco-certified intangible cultural heritage.

Top image by Joshua Lee

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.