My name is Captain Ho Weng Toh. I'm 98 years old, and I am the last Flying Tiger alive in Singapore, and all of Asia.

The Tigers were a group of volunteer American pilots who fought against the armies of Imperial Japan in China. I trained in Pakistan and America, and served in the Chinese-American Composite Wing of this group while fighting in China.

Born in Ipoh, had aspirations to study in China

I live in Singapore now, but I was born in Ipoh, Malaysia, in 1920.

In those days, Malaysia was still a colony under the British. I grew up in a shophouse in town.

My father immigrated from China. He was a stern, traditional man who still used ink brushes to write. He closely followed the teachings of Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary Chinese leader.

He had a different view of life, compared to today. He told us about his tough childhood in China. Every day, he said:

"You must struggle. You must endure."

I was the eldest son in the family, but I had five older sisters. As you can imagine, I was spoiled rotten.

But my father felt responsible for grooming me. He shared with me the ideologies of Sun Yat-sen and Confucius. He also taught me Chinese history.

The Opium War had occurred not too long ago, and we lost everything. China was occupied by foreign powers, and had to sacrifice its territory. Cities like Hong Kong were colonised, and China lost a lot of prestige.

[related_story]

But due to my father's influence, I wanted to study in China one day.

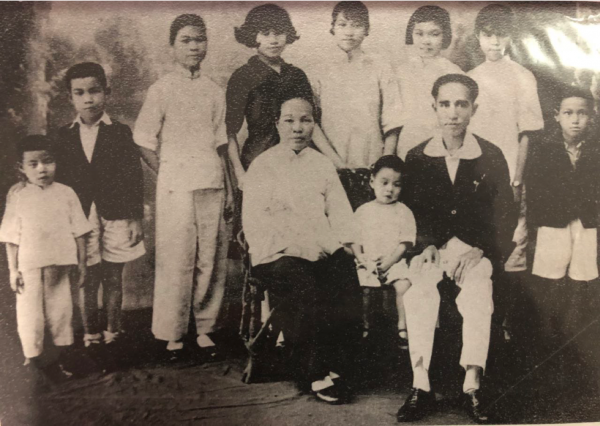

Captain Ho (2nd from left) and his family in Ipoh, Malaysia. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho (2nd from left) and his family in Ipoh, Malaysia. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

A shot at a better life

The education system in Malaysia back then wasn't very developed. You had primary and secondary school, and eventually sat for the Senior Cambridge examinations. But options were limited after that.

Most people stopped there, or went to commercial school to learn typewriting and shorthand. Afterwards they could work as a clerk. Only those who could afford it went overseas to study.

I wasn't much of a student, but I dreamed of studying overseas. I wanted a chance to improve myself. Otherwise I would be like hundreds of other local boys, living an ordinary life.

I thought my father couldn't afford it. But he told me not to worry, and to go meet my uncle.

My uncle had become a rich tin miner, after my father helped him to settle down in Malaysia.

He was so happy when I asked him about studying in Hong Kong. He said:

"‘You must go! You are the eldest son. Your father took care of me, now I must take care of you."

He agreed to pay my way without hesitation.

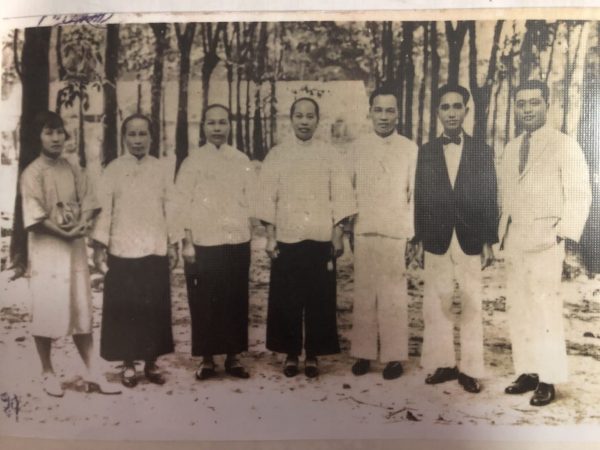

Captain Ho's uncles and aunts. His father is 2nd from right, the uncle who paid for him to go to HK is on the far right. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho's uncles and aunts. His father is 2nd from right, the uncle who paid for him to go to HK is on the far right. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Coming to Hong Kong

First, though, I had to qualify. I only had a Senior Cambridge 'O' Level, not an 'A' Level. In those days, the Malaysian curriculum was quite limited.

They didn’t teach higher mathematics, physics or chemistry. You needed to matriculate before you could attend university.

I went to St Stephen's College, a secondary school in Stanley, Hong Kong, just to get the necessary certification. But the war would change things.

The prestigious Lingnan University came down from Guangzhou after the Japanese invaded China in 1938. They used the premises of Hong Kong University to conduct their classes.

Lingnan accepted students with 'O' Level qualifications, so I left St Stephen's to enrol there.

First taste of politics

It suited me quite well. The classes were held in the evening, so I had my days free to study for my matriculation. But the classes were conducted in Chinese, and I wasn't fluent enough.

So I attended a class for Overseas Chinese students, ran by one professor. Now this man happened to be a disciple of Sun Yat-sen himself.

While my father had discussed Sun Yat-sen’s teachings with me, this professor could expound further on his ideology of the Three People’s Principles, or Sanmin Zhuyi.

I was very inspired, it was an enlightening experience. Politics wasn't a common topic back home, but here we discussed the principles of democracy, freedom, and other ideals.

No one was more surprised than me when I managed to pass my matriculation. I left Lingnan and joined the University of Hong Kong's (HKU) science faculty in 1940.

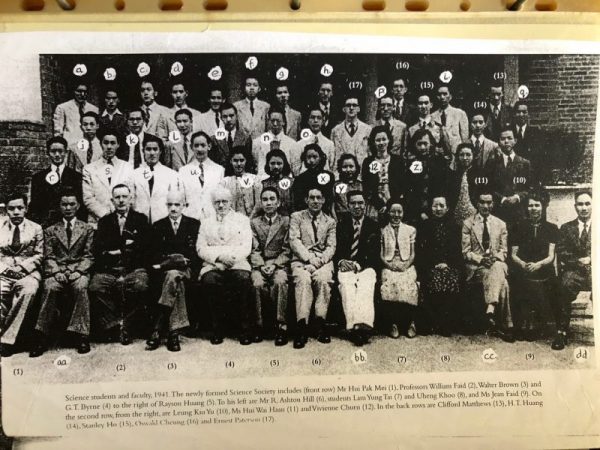

The science faculty in HKU. Captain Ho was absent the day the picture was taken. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

The science faculty in HKU. Captain Ho was absent the day the picture was taken. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

University days

I enjoyed my time in HKU. It was run by the British, so the system was similar to schools like Cambridge and Oxford. It had a wonderful campus and well-run hostels.

It wasn’t like my student days in Malaysia, where they monitored you all the time. Here, you were on your own. You decided if you wanted to attend lectures or do research. If you wanted to do nothing, that was up to you too.

This tested my resolve when I joined the student union. They organised many functions, like dinners and dances. I enjoyed them, but they were also distracting.

The other students were very clever, well ahead in their math and sciences. I was behind in my own studies.

We kept up with world affairs too. The Japanese were invading China, but the political situation in Europe was also brewing. Adolf Hitler and Germany were too powerful, he even bluffed the UK Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in Munich.

We knew the war was coming. Germany had invaded France, conquered many places, and the UK was fighting back. And of course, Germany was together with Japan at the time in the Axis.

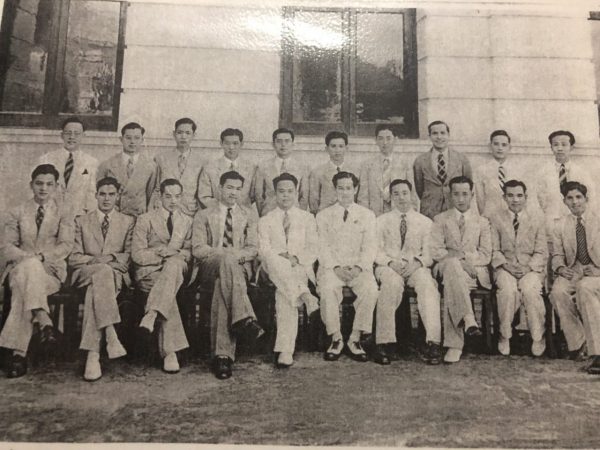

Captain Ho (seated, 2nd from right) and his schoolmates, months before Pearl Harbor. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho (seated, 2nd from right) and his schoolmates, months before Pearl Harbor. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

The fall of Hong Kong

I remember studying for my exams in my hostel in December 1941. Suddenly, I heard sirens. My room was quite high up, and feeling curious, I went outside on my balcony to take a look.

I saw planes hovering around Kai Tak Airport, dropping bombs. It had to be the Japanese. I went back to my room and turned on the radio. They announced that war had broken out. The Japanese were bombing Pearl Harbor, Singapore and others.

Could you believe it? A fellow like me, ill-prepared and studying for exams, and war had started. At that moment, my mind worked very fast.

“You’re here now and the war is on. You’re on your own. You have a lot of figuring out to do.

You may not be staying at the hostel for much longer, where are you going to go? Your parents and village are far away, how are you going to survive?”

All these things came to my mind. That one moment made a lot of difference.

Then all the students gathered in the common room. Everyone was at a loss. There was little we could do, except wait for further developments. We knew that the British had a few soldiers stationed in Hong Kong, but they would stand no chance.

Japanese troops reach Hong Kong. Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

Japanese troops reach Hong Kong. Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

"You could get hit by shrapnel at any time"

The Japanese crossed the border of Shenzhen and occupied the New Territories, on the Kowloon side. But they continued shelling the city. It was dangerous, you could get hit by shrapnel at any time.

I was afraid. The Japanese were the people my father had been telling me about, how cruel they were and how badly they treated the Chinese.

But even when the Japanese took over Hong Kong completely, they at least allowed us to stay at the hostel. We were even given some beans to eat. In that sense, we were lucky. We had a roof, water, light and some beans to survive.

There were a group of four boys and four girls that I became close with. We met every day to talk and make plans. We talked about escaping to Free China, the parts of China that were still fighting back against Japan.

There were many question marks, but just talking to each other strengthened us and gave us courage.

Captain Ho (standing, extreme left) with fellow students during Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. Pic courtesy of Fred Ho.

Captain Ho (standing, extreme left) with fellow students during Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. Pic courtesy of Fred Ho.

Got baptised for "insurance"

Hong Kong fell in December 1941. My experience of the Occupation was exactly like how it had been described to me, the cruelty of the Japanese and how badly they treated our people.

There were no courts, no police. They were in power, so they could d0 anything they liked.

Things were uncertain. I attended a Christian school back in Malaysia, but I didn't think about baptism then. I thought if I died without being baptised, I wouldn't go to heaven.

So I went to the French convent in Causeway Bay and asked the priest for a baptism. He asked me a lot of questions, but I said I wanted to be baptised on the spot. I think he couldn't refuse my sincere wish.

I had "insurance", so to speak, but you can't live in a situation like that for long. There's no education, no future, nothing.

To survive is very tough, and even if you do, you can't face this kind of people in charge.

Japanese Lt. General Sakai enters Hong Kong. Pic via Thoughtco.

Japanese Lt. General Sakai enters Hong Kong. Pic via Thoughtco.

Hiding a group of rape victims

But when things were tough, we had to help each other.

A female classmate of mine had moved from Kowloon to Happy Valley, so I went to visit her place, where she was staying with some friends.

They were all crying when I arrived. They said that Japanese soldiers had raped the group of women, and they felt helpless.

I remembered my friends who lived in Causeway Bay, an Indonesian family. I went to them and opened my big mouth.

I was going to ask for a very tough favour. Food was difficult to find. The family had five children and two maids, a total of nine people.

But I told them about my friends. And they said:

"No, no, you bring them here."

I said that I couldn't burden them, but they told me not to worry. All of us were in the same boat. I brought the ladies over to the Indonesian family two at a time, avoiding the Japanese sentries.

Fortunately they got along well, as their families knew each other. I still keep in contact with the family today. They even came down from Hong Kong to celebrate my last birthday.

These are the things I did that had some kind of payback. I believed that because I helped people, I was in turn allowed to get out of some troubles later on.

The ladies were safe for the moment, but I couldn't hang around. There was no future for me in Hong Kong.

Florence, one of the ladies Captain Ho helped to safety in Hong Kong. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Florence, one of the ladies Captain Ho helped to safety in Hong Kong. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

An unexpected patron

There was a professor named Reid at HKU, who was also a colonel in the British Army.

Before the invasion, he encouraged Malaysian students to join the Red Cross. He saw the need for volunteers when war broke out.

When the Japanese took over, he was caught and put in a camp. But there were many spies from Britain and Free China in Hong Kong. With their help, he escaped to Guangzhou.

He then set up a relief council to help people who were fleeing Hong Kong. But we had no money or resources to reach Free China.

But one day we got the chance to meet with one of the Tiger Balm pioneers — the old man himself, Aw Boon Haw.

We visited his pagoda in Causeway Bay. Over tea, he asked us all kinds of questions, and said we are young and should escape.

He donated HK$500 to each of us, out of the blue. On top of that, we could help ourselves to supplies of ointment from his shop at no charge. Because of his help, I could make the escape. The money made a lot of difference.

Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

Fleeing by truck, boat & on foot

In May 1942, we were told by the spies to gather behind Peninsular Hotel at 3 o' clock in the morning. We disguised ourselves in dark clothing and piled into two trucks headed for the New Territories.

That was very frightening. We had to bypass many sentries along the way. If they caught us, our lives would be over.

We reached a small fishing village, but it was garrisoned with Japanese soldiers. There were some naughty kids who told them we were coming.

The ladies hid in a tall building while I acted as a decoy with a few other guys. We pretended to go up to a boat so they would think we were sailing away.

The Japanese came up to the boat, armed with rifles and bayonets. They were angry, aiming their weapons at us and shouting:

"Where are they? Where are the rest?"

We said there were no ladies here, just us guys. They looked around and found nothing. After they left, we quickly made the crossing into Free China on foot.

Even though there were no Japanese soldiers after that, our troubles weren't over. There were Chinese bandits roaming around. They said they would protect us, but still demanded what little money we had. We had no choice but to pay up.

Fortunately, we managed to reach the East River and sailed up it by boat. Next we sat in an old truck that took us to the council in Northern Guangzhou.

It was a tough journey. It took 10 hours on a rickety truck that went through ravines. But at least we made it there safely.

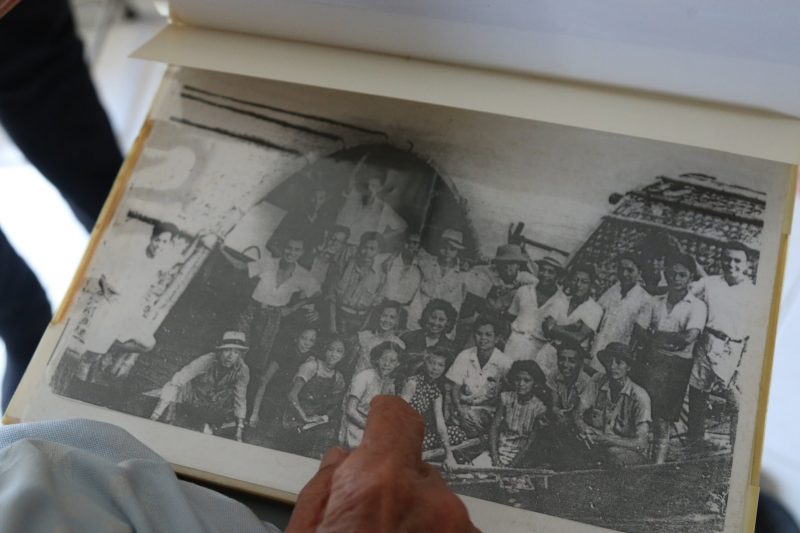

Captain Ho looks at a photo of the boat that took the refugees to Free China. Captain Ho is on the left, standing, in the white shirt. It was 1942, and he was 22 years old. Photo by Jason Fan.

Captain Ho looks at a photo of the boat that took the refugees to Free China. Captain Ho is on the left, standing, in the white shirt. It was 1942, and he was 22 years old. Photo by Jason Fan.

Joining the war

I made it to Free China, but it was a makeshift life. The Japanese were nearby, and they kept us moving. I stayed with a compassionate pastor who took me in. Our hosts knew that we were refugees in dire straits.

I couldn't contact my family. I was worried, but had to take care of myself.

I survived for months only two main foods — soya beans and tangerines. For dinner, I might have steamed rice with a single egg. And that was all I could afford. But it kept me alive.

One day I saw an advertisement calling for volunteer pilots to join the Kuomintang. I decided to sign up, even though my friends said I didn't have the stature to be a pilot.

But they were interested, and I went down to Guilin to sit for physical and written examinations.

And it just so happened that the exams asked about Sun Yat-sen's Three People's Principles, which as you recall I studied in Lingnan University. I couldn't believe my luck, but that was also how I was able to pass.

The final hurdle

After that, I just needed to find a sponsor. I was 22 years old, an uncouth-looking refugee student. For months, I tried to find someone to sponsor me, without success.

But the pastor I was staying with said he had a lead for me. He made an appointment with a man who could be my sponsor. This was a young brigadier-general in the Kuomintang.

We met at his house. He was dressed in uniform, and asked me about my past. He was quite impressed with my story.

"You came all this way to join the Air Force? It's already dangerous enough just to survive."

I said no, I was willing. I felt fortunate to be called on to serve. To me, my life didn't matter. This was the right path to take.

The general went into a backroom, came out with a chop for my papers, and formally became my sponsor. My heart filled with relief.

I was so happy that I forgot to get his name, which is one of my biggest regrets. I would like to thank him, because he made it possible for me to become a pilot and take part in the war.

Captain Ho's story continues with Part 2, here.

Related story:

Top image via Thoughtco & photo by Jason Fan.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.