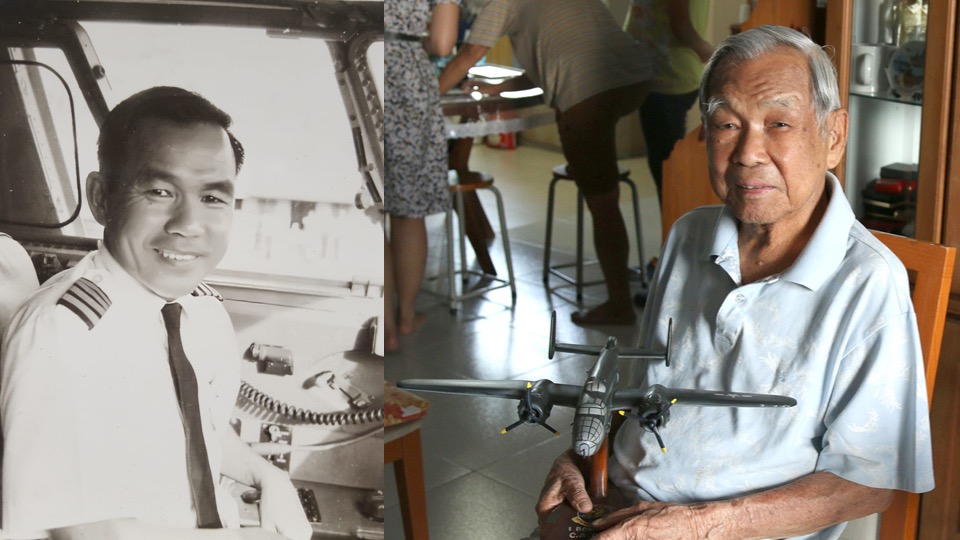

This is Captain Ho Weng Toh.

CPT Ho Weng Toh. Mothership photo.

CPT Ho Weng Toh. Mothership photo.

He is 98, and is the last of the Singaporean Flying Tigers — a collective of pilots who fought alongside the Chinese and Americans against Imperial Japan in China.

He has told us some parts of his extensive and storied life, which we've compiled into these two parts:

If you've read them, you'll have heard about his amazing journey to becoming a military pilot, and also his thrilling but also bitter experience bombing the Japanese during WWII, his post-war exploits in Shanghai and the nail-biting journey he would end up taking to Singapore with his wife.

CPT Ho (2nd from right) in 1943 during his time as a fighter pilot. Courtesy of CPT Ho Weng Toh.

CPT Ho (2nd from right) in 1943 during his time as a fighter pilot. Courtesy of CPT Ho Weng Toh.

But of course, there's plenty more to Ho's story, and also plenty more that this "Super Pioneer Generation" (as he likes to refer to himself now) Singaporean achieved in the years since sinking roots here with his very international family — not just for himself, but in a big way for the Singapore aviation industry and its growth.

Joining Malayan Airways

After the Sino-Japanese war, the civil unrest in China forced Ho and his wife to fly to Singapore. They came here in 1951 and Ho put his war-pilot skills to good use by working with Malayan Airways Limited (MAL) as a commercial pilot.

[related_story]

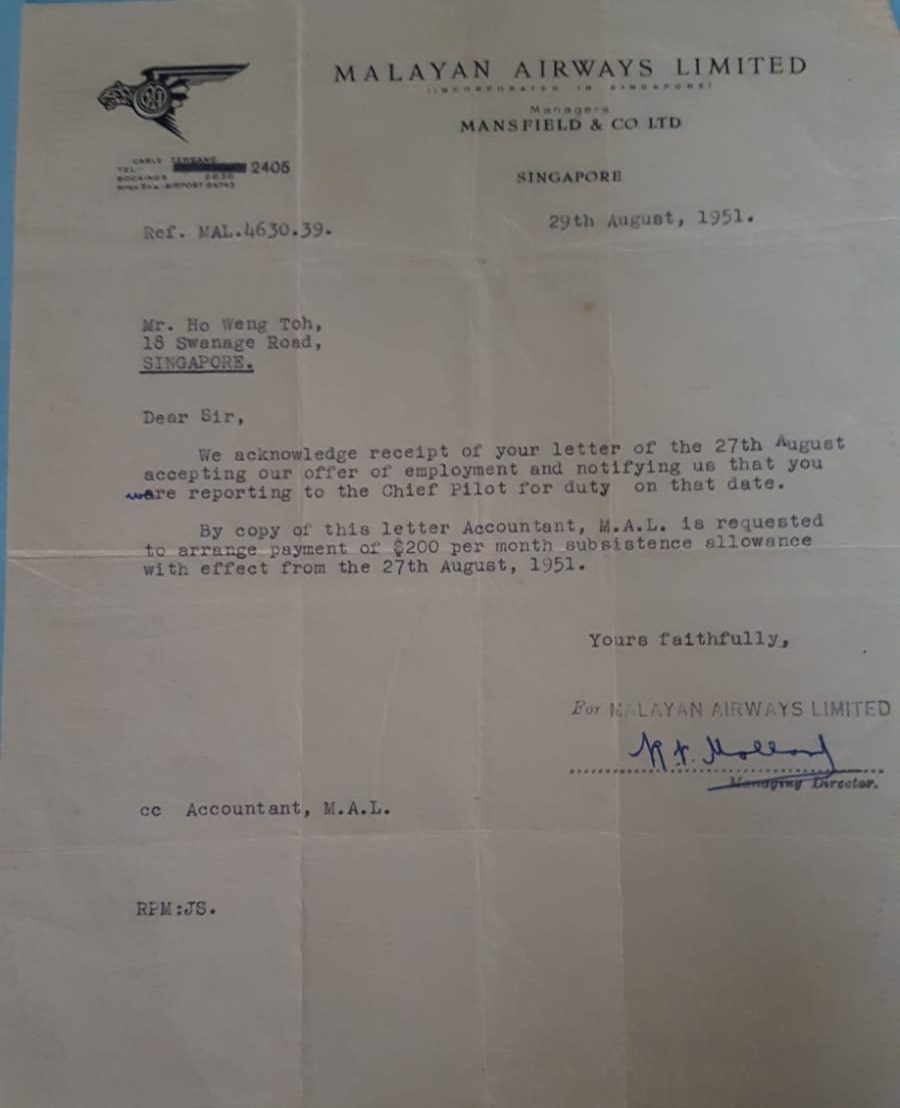

Here's the confirmation letter he received when he first joined MAL, which details his starting monthly pay of S$200:

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Ho started as an entry-level Second Officer with the airline, even though by the time he joined MAL he already had thousands of flying hours under his belt, more than the higher-ranked European officers and captains.

Despite this, MAL did not count Ho's wartime experience or time spent training in China as recognised flying experience, so he had to pay for flying lessons and get certified in Singapore:

"Flying lessons were very expensive. It cost you S$100 an hour, cost you a fortune. It took 120 hours to pass. Now, it’s the same. At that time, it was a lot of money. At the time, a bowl of noodles cost about S$0.80.

Even those boys who joined SIA still needed to build up their experience. They couldn’t fly on their own at first, people paid for them, subsidised them. But for me, they did not recognise my flying (experience) in China. I had to sit for the air law (test) and I had to do certain flying. I had to pay for my own."

That issue notwithstanding, Ho's aptitude accelerated his promotion to First Officer within months of joining.

He went on like this, and when he was about three years into the job, Ho realised that as a First Officer, there was an odd discrepancy between his salary and those of his European and American First Officer counterparts — while they earned S$950 per month, he was paid S$750 instead.

And it wasn't for want of experience, as we've elaborated above.

"We were doing the same job, except my colour was different. That one (the pay difference) I strongly objected to and was very upset about this sort of thing."

Which brings us to...

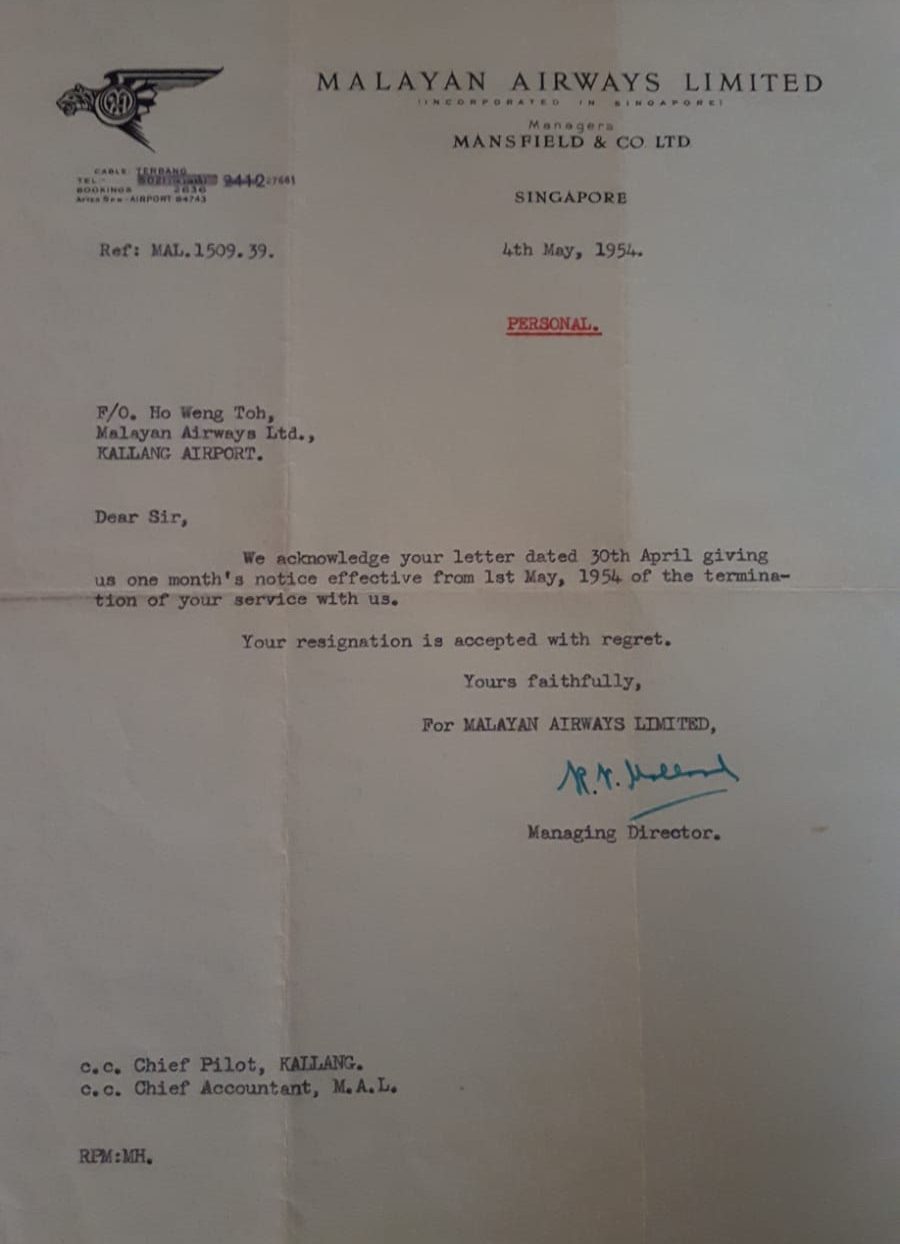

The epic ragequit

At the same time, Ho was being actively courted by two old pilot friends who were flying for a company that delivered the Nanyang Siang Pau to Penang and Ipoh in the mornings on a light aircraft.

As there was a vacancy for a third pilot, Ho recommended a friend he had made in Hong Kong to take up the position as he was already employed, and aware that in those early years, MAL was still short of pilots and so it wouldn't be good if he left.

Tragically, though, the friend crashed the aircraft in Kuala Lumpur on one morning's flight and died.

"I felt very bad for the family... so of course I had to think about it (the job offer) because I was thinking... it was not good to leave now, especially because that sort of flying was very tough flying. Early in the morning, every morning."

So it wasn't ideal, but with this weighing on his mind, Ho confronted his predicament at hand and the inequality he experienced as a local pilot at MAL, and decided to take the plunge and resign — even though this meant he would lose his seniority in doing so:

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Regrettably, though, the company would soon afterward fold, and Ho found himself out of a job.

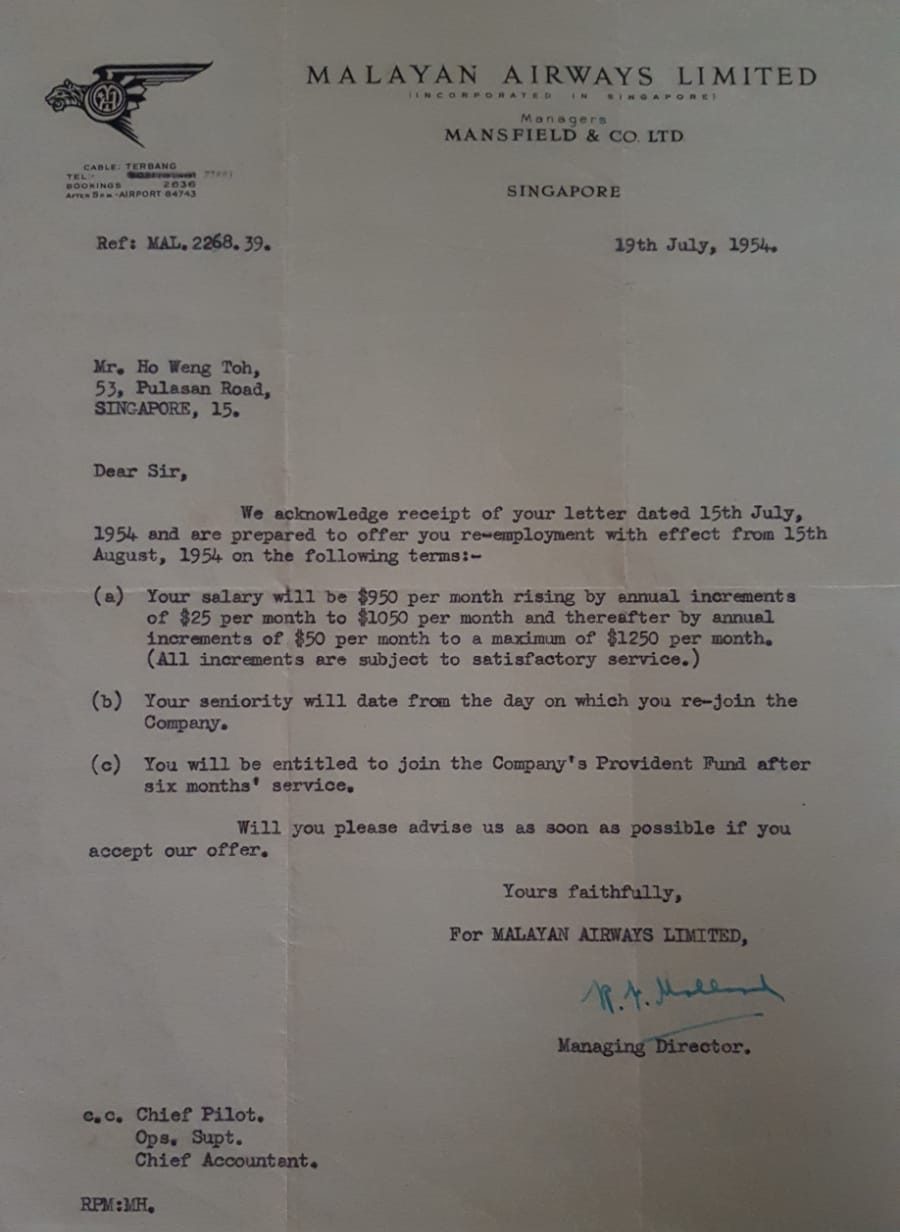

But being aware of the shortage of pilots (especially experienced ones like him) at the MAL, he discovered he would still be able to find leverage against the airline's then-Managing Director.

To his somewhat surprise, MAL's boss accepted his return, just two and a half months later, with open arms — and a renewed equal pay:

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Image courtesy of Fred Ho

Nice. But that would be just the beginning in his decades of effort to advance the cause of locals (by his definition at the time, Singaporeans and Malaysians) in the aviation industry, throughout his flying career.

Training four generations of local pilots

One of the things Ho advocated was the Malayanisation of the airline — to have the service staffed by locals. It was a movement that was in tandem with the civil service.

"For us, we talked about Malayanisation. At that time, our fleet was very small and our international routes was not that strong, only to Hong Kong and Japan.

Those days there were no pilots. There was no aviation school. People just came in after their service in the Air Force. We didn’t even have a proper Air Force, just an auxiliary Air Force. They did preliminary flying, then joined SIA."

Capt Ho (far left) with fellow local pilots under MAL. The DC-3 is behind them. (Photo courtesy of Fred Ho)

Capt Ho (far left) with fellow local pilots under MAL. The DC-3 is behind them. (Photo courtesy of Fred Ho)

The late 1950s would see Ho receiving and taking under his wing the first eight local pilots who would join the airline between the mid-1950s and 1960.

Another 10 locals who received grants and scholarships, including four who received the prestigious Colombo Plan Scholarship (somewhat equivalent to today's President's Scholars), trained overseas for varying periods before returning to additionally learn from him.

Ho was finally promoted to Captain in 1961, and from there, he developed learning programmes that would see through more than the four generations of local pilots trained by him, on three different aircraft: the Douglas DC-3, the Fokker F-27 Friendship and the Boeing 737.

Captain Ho with the Boeing 737. By this time, the SIA brand was formed following the split of the Malaysia-Singapore Airline. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

Captain Ho with the Boeing 737. By this time, the SIA brand was formed following the split of the Malaysia-Singapore Airline. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

Today, Singapore Airlines has more than 2,000 Singaporean pilots — some 10 generations of men and women trained for this challenging, yet still-very-respectable occupation. Ho estimates he has personally trained more than 200 of these, and they now affectionately refer to him as "Daddy-O".

But he didn't stop there.

Establishing the first local pilots' union

Ho believed that local pilots should be receiving the same pay and perks as expat pilots. It was an ongoing struggle for him, and for his fellow local pilots who shared his strong belief in the cause:

"The British, American and Asian pilots were completely different. The expatriates have been trained, either in the military or commercially. They were ready-made. But they had perks that we local boys didn’t get... they had perks worth much more. But without them, we also could not fly."

Ho said it was particularly tough for cabin crew — there were no male stewards until the mid-1960s. There would be one single crew member serving 28 passengers on a return journey:

"It was very tough work, I tell you. They served hot food, a full breakfast, (to) fly from here to Borneo, (she would) work 12 hours on her own, serving coffee from a thermos. In those days the aircraft were not very stable either."

He felt so strongly about this that together with a few others, he established what was initially called the Malayan Airways Local Pilots Association (MALPA) in 1958.

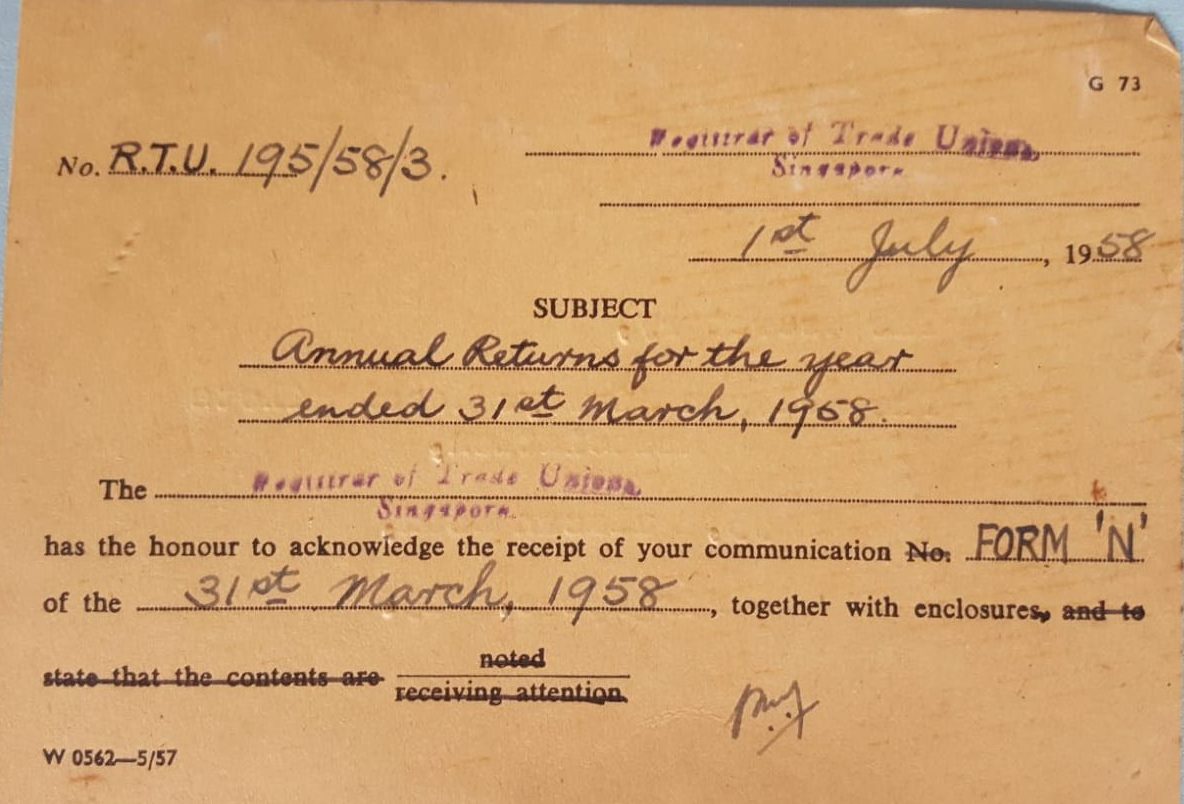

The MALPA was registered formally as a trade union in end-March, 1958. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

The MALPA was registered formally as a trade union in end-March, 1958. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

The first meetings, and the union's address, was registered to Ho's personal residence — 53 Pulasan Road. Ho was the association's general secretary.

But because there were too few local pilots at the time — around 15 compared with some 30 expatriate pilots altogether — Ho said the association had little teeth, and even when they sought the assistance of larger union bodies, it was tricky.

The LKY connection

Ho says it was only when they got in touch with the late Lee Kuan Yew and his buddies who would go on to become Singapore's first-generation leadership that they managed to make inroads to their efforts to improve working conditions for locals.

The late Lee, who while still a lawyer would take planes flown by Ho himself, became legal advisor to the MALPA, and folks like the late unionist and President Devan Nair also stepped up to work closer with them.

"By the 1950s, he (LKY) was already well-known among the expats, that he was going to be the leader, and they have to respect him... (His representation was) So effective that the guy just had to turn up and they (the expats) immediately agreed. They didn't even have to talk about it. Just because of his presence — he didn't have to do any work."

The MALPA would eventually morph into the very robust Air Line Pilots Association-Singapore (ALPA-S), which Ho continues to be a member of and attend meetings at, by the way(!).

And Ho's relationship with the late Lee would also endure — going from flying Lee, as a lawyer, to Borneo for business, recalling how the late Kwa Geok Choo (LKY's wife) would wait to receive him at the airport, baby in arms, to flying Lee as Prime Minister to ASEAN meetings around the region in the Boeing 737.

For union activities, Ho would also find himself at Lee's famous Oxley Road home to meet with him on matters regarding the MALPA so Lee could negotiate with the British on their behalf.

And on one fine day in 1967, when Ho was sitting in a National University of Singapore lecture theatre doing "extra studies" in International Law (as if he wasn't busy enough), Lee came by to visit and singled him out from among the crowd to ask what he was doing there.

"Out of the whole class, such a big class a few hundred, you know, during his walkabout, (LKY) recognised me so I stood up and he said "what are you doing here? Aren't you a pilot?"

So that impressed all the local boys and girls. They still talk about it today and say 'hey he recognised you!'"

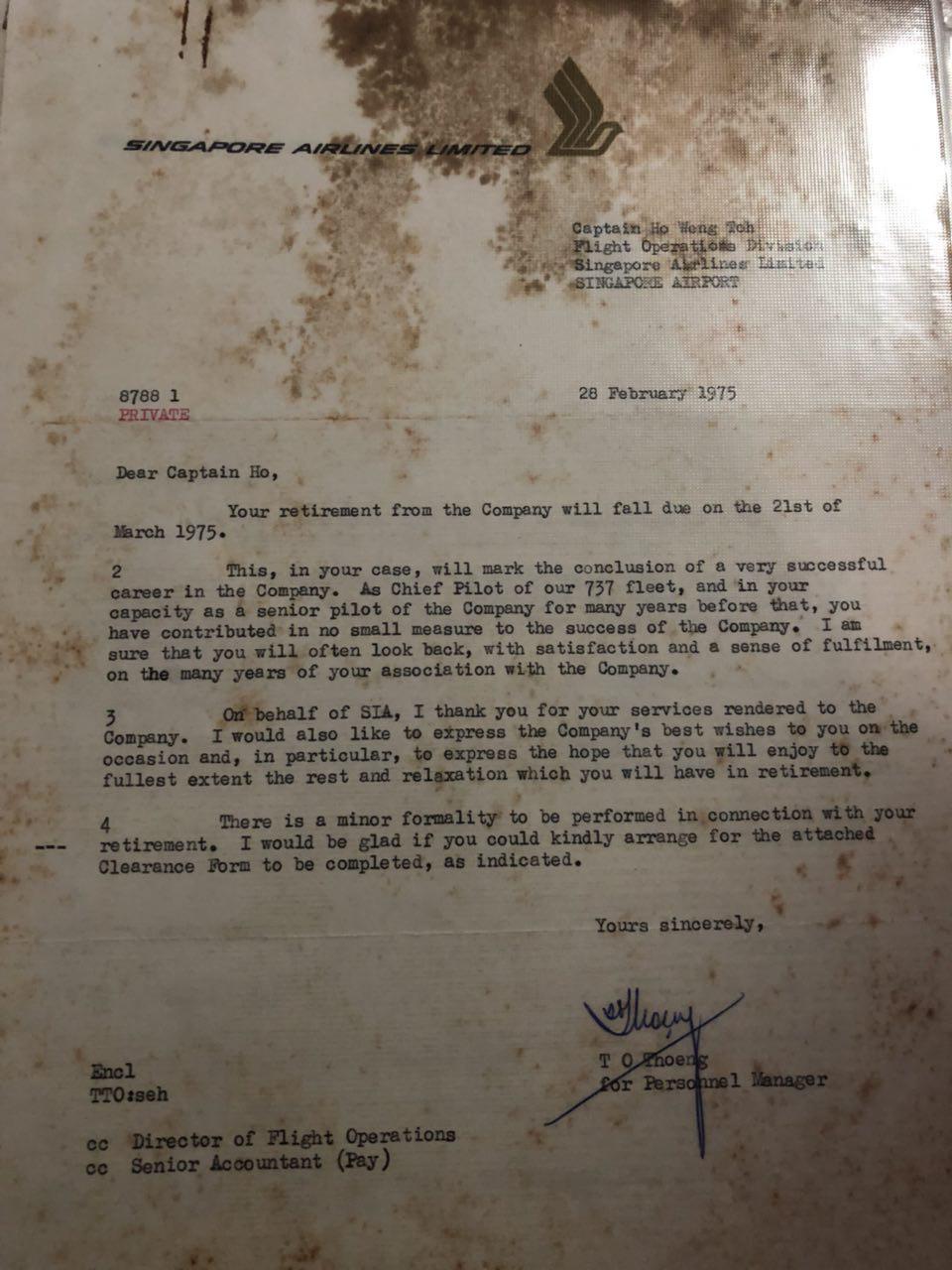

Ho became Chief Pilot for Singapore Airlines's Boeing 737 fleet in 1974. A year later, he was slated to retire, but such was his commitment to the airline that he immediately signed a new contract two days later (you can see the letters praising his contributions below) to continue his work:

Ho's retirement letter dated February 1975, courtesy of Capt Ho

Ho's retirement letter dated February 1975, courtesy of Capt Ho

Ho's reemployment letter dated March 1975. Photo courtesy of Capt. Ho.

Ho's reemployment letter dated March 1975. Photo courtesy of Capt. Ho.

And when he actually did retire, Ho and a few others established the SIA Group Retired Staff Association — which of course, he still plays an active role in.

One of their early meetings. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

One of their early meetings. Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

Here he is seated at a dinner with former SIA chairman J Y Pillay (Ho is on Pillay's left in this picture, with other union members):

Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

Photo courtesy of Fred Ho

Fast forward 43 years, Ho is now a sprightly 98-year-old who has long retired from SIA.

He still regales us with stories about his flying days during the war and after that, with the airline. Listening to him, we can't help but admire his courage and tenacity — the OG in supporting local.

Top images courtesy of Fred Ho, by Jason Fan

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.