98-year-old Captain Ho Weng Toh is the last surviving Singaporean Flying Tiger — one of a group of World War II pilots who assisted a Chinese-American coalition in fighting the Japanese in Asia. Ho has had one heck of a life, and he shares part of it with Mothership in this two-part series of interviews — in his own words, which are shortened and slightly edited for clarity.

Escaping from Japanese-occupied Hong Kong was difficult and dangerous, but I was finally accepted for flight training. However, it would be some time before I would actually get to step into a plane.

We gathered in Yibin, south of Chungking. Today the city is known as Chongqing, the place where General Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang army retreated to after they lost the Battle of Nanking (Nanjing).

Chongqing is surrounded by hills and not very accessible by roads or air, which made it a good place to lie low. But this meant that Chiang was also confined there.

Yibin was also not a good place for flight training.

- There weren't enough airplanes.

- They didn't have enough fuel supplies, and

- We were harassed by the Japanese.

They knew we were there and disrupted us by making bombing runs. The weather was poor too, with low clouds, fog and mist.

Military-style training, decades before NS started

We then moved further south to the city of Kunming for two months of pre-flight training. We marched around and took classes on politics. It was gruelling for me, as this was my first taste of military life.

I had to wake up every morning before dawn, and meticulously make the bed. I never needed to do it before, so I found it very troublesome.

[related_story]

After that, it was time for breakfast. It was very strict, they just gave you three to five minutes to gobble down your food. It was all part of the training, to instil discipline.

Luckily, I made friends with a Tibetan guy named Kasun Chupe. He had a military background, and had no problem making the bed or complying with the other rules. However, he couldn't speak English very well, so he stuck close to me and I helped him.

I didn't mind looking after him — in return, he helped me to make my bed. That solved the problem.

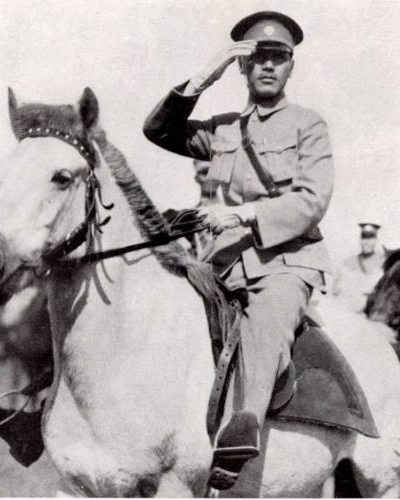

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Pic via Wikimedia Commons.

The privilege of having a passport

After breakfast, it was time for physical training. You had to run a few kilometres every morning, perhaps the distance of the journey from Pasir Ris to Tampines and back again.

Again, I wasn't prepared but I had to do it. I bit my lip and knew that I had to suffer together with my friends.

I thought about giving up many times. But I couldn't afford to. If I dropped out, I would have trouble finding a place to stay, with little to survive on.

Finally, I was selected for further training. The authorities decided to send us to India, which at the time was still governed by the British.

Back then, I only held the passport of a British Protected Person under the Sultanate of Perak. I wasn't a subject of the crown or a citizen of Britain, it was a very lowly kind of status. The passport didn't allow you to travel to many places.

The officials told me that I needed a proper Chinese passport so I could travel to India and then America for training. They gave it to me, and I felt very proud. It was a big thing for me, to have a nationality for the first time.

The advantages of knowing English

180 of us went to India. Most of the cadets needed my help, because their command of English was poor. So I became rather popular.

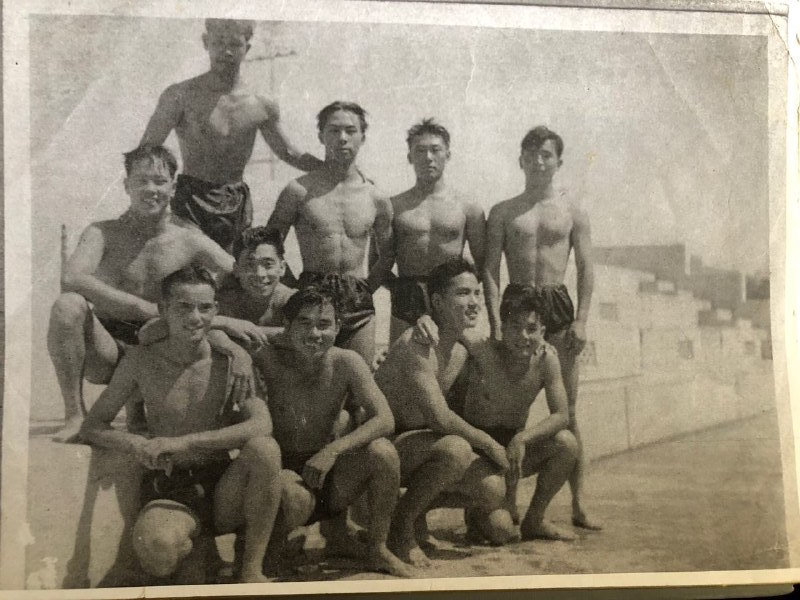

Lahore, 1942. The cadets went swimming before the airfield was opened. Captain Ho is in the bottom row, second from left. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Lahore, 1942. The cadets went swimming before the airfield was opened. Captain Ho is in the bottom row, second from left. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

India felt very familiar to me. It was almost like going back home to Malaysia, where there were Indian families who could also speak English. I was brought up in Ipoh with many Indian friends, so I had no problem.

The other (ethnic) Chinese cadets had problems though, some of them had never even met an Indian person before. Their countries were completely different.

We had to camp near a jungle in tents while waiting for the train. There were no proper buildings, just a fence that separated us from the jungle. At night, we could hear the wild animals moving about, maybe tigers and elephants. Luckily, we only had to wait for a few days.

We journeyed across India by train in private carriages. It was interesting as I learned about these cities in school, like Calcutta, Assam, and Bangalore. The further we travelled, the more names I recognised.

We stopped at big stations along the line, like Calcutta and Lucknow, and had the chance to stretch our legs. I remember British ladies from the Red Cross walking around the stations, selling poppies to raise funds for the war and relief efforts.

Eventually we reached Lahore, which at the time was part of India (today it's in Pakistan). We trained there without worrying about the Japanese.

Friends made — and lost

Unfortunately, during my time in India, a tragedy occurred.

I had a friend in India with me. His name was Doong Siew Meng, and he was with me in Hong Kong. We escaped to China together, traveled to India and trained together.

Doong Siew Meng. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Doong Siew Meng. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Doong was a very clever and knowledgeable chap. I thought we would fight the enemy together too.

However, tragedy struck. During a test flight in India, Doong crashed his plane. He died, and I lost one of my close friends.

It was tough. But I had to move on.

Next, my squadmates and I went to America for extended flight training. We were there for about a year.

I was then assigned to the 1st Bomb Squadron of the CACW in Hanzhong, Shaanxi province. The base was unique, housing both American and Chinese forces.

Captain Ho is 2nd from the right, standing. Flight training in Thunderfield Field in Arizona, in front of a PT-17 Stearman aircraft. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho is 2nd from the right, standing. Flight training in Thunderfield Field in Arizona, in front of a PT-17 Stearman aircraft. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Finally taking flight in the war

I flew a B-25 Bomber, a medium bomber and a very versatile plane. Unlike a heavy bomber, which couldn't fly close to the ground, or a light plane, which couldn't fly up high, the B-25 could go both high and low.

The bomber had a crew of six. Two pilots, two gunners, a bomber and a navigator. I was one of the pilots. The bomber and navigator were Americans, while the rest were Chinese.

I felt excited to finally take part in the war. All the training I've been through, all the trials and tribulations, it was all leading to that moment.

Unfortunately my first mission was abandoned due to the poor weather. The Japanese were winning the war. They had occupied the whole of northern China and were coming down south.

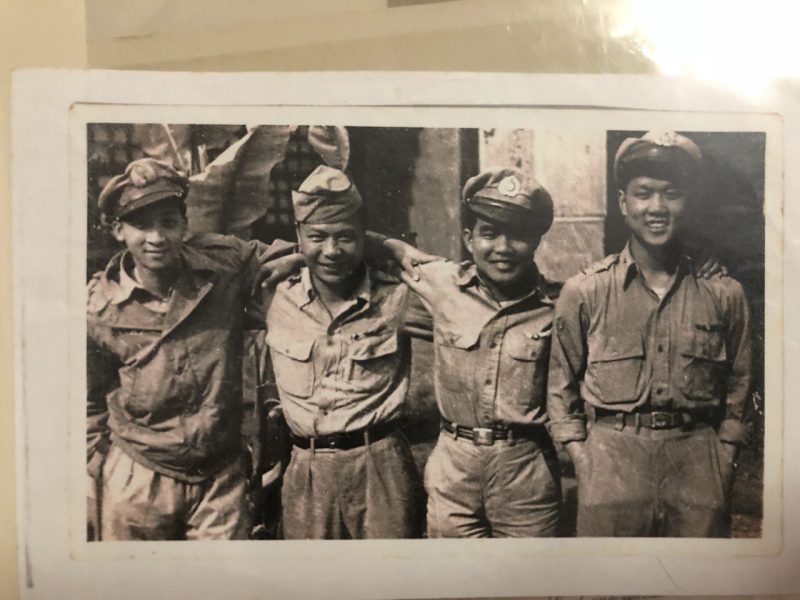

Captain Ho (2nd from right) and fellow pilots during WW2. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho (2nd from right) and fellow pilots during WW2. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

They wanted to encircle Sichuan and Chongqing, where Chiang was. Our objective was to stop their advance and deter them from moving south.

"I... saw them leap up in shock. They knew they were trapped"

But on the second mission, I saw the enemy up close for the first time.

It was a group of Japanese cavalry. I approached and saw them leap up in shock. They knew they were trapped, and couldn't escape the bomber. I flew low and strafed them with the machine guns, and dropped a few small bombs as well.

It was cruel, but it was also an achievement. You feel great, but it was also quite inhuman.

It was war. If you don't kill the enemy, they will kill you. It's best not to go to war in the first place.

A B-25G Bomber. Pic from U.S. Air Force, via Wikimedia Commons.

A B-25G Bomber. Pic from U.S. Air Force, via Wikimedia Commons.

After that, we did mostly high-level missions. We would bomb warehouses, railway centres, that sort of thing, to slow down the enemy's advance.

My most memorable mission was when I went up together with five other planes, all flying in formation. To assemble in formation is not easy, and neither was flying or bombing.

The Japanese were ready for us, firing anti-aircraft guns. When I came back, my wings were full of holes. If they hit my fuel tank or propellor, I was finished. No matter how scared you were, you had to stay in formation.

But I was lucky too because the Pacific War was heating up, so most of the Japanese planes were drawn to that theatre. In all, I flew on 18 missions.

There was a big celebration when the war ended. I told myself:

"I'm alive. There's a future ahead for me."

I was still young and had a long way to go, but I had also become a citizen of a country. China was a great country, and finally at peace. There was a lot to do, but there was much to look forward to as well.

I was full of hope.

Captain Ho (2nd from left) and fellow pilots after the war. His plane, called "Hey Mabel", is in the background. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho (2nd from left) and fellow pilots after the war. His plane, called "Hey Mabel", is in the background. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

"Pilots were suddenly the most eligible men around"

After the war and the Japanese surrendered, I was stationed in Hankou, Wuhan as an instructor. I was just 25 years old at the time.

The Americans wanted to leave and go home as soon as possible. I was sad to say goodbye to my friends, who called me "Winky".

But I had a good time in Hankou, which we called the "Chicago of China". We played bridge and talked about our war experiences.

We were young and eager, and had many sweethearts. Many Kuomintang generals sent their families to Hankou to take refuge. It was relatively well-protected, with an airbase.

One of many of Captain Ho's friends in Hankou, nicknamed 'Teng How', in 1946. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

One of many of Captain Ho's friends in Hankou, nicknamed 'Teng How', in 1946. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

The girls were lonely and didn't know anyone, and us pilots were suddenly the most eligible men around.

But when Mao Zedong's communists rose up to wage war against the Kuomintang, I was asked to join this new war. I was very reluctant. This was not my war.

Fighting the Japanese was one thing, but not my own people. I made up an excuse to return to Malaysia instead to visit my family.

Still, I didn't want to leave for good. I had a very compelling reason to linger around in China — wooing the girl who would become my wife.

Captain Ho's late wife, Augusta. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho's late wife, Augusta. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

A dramatic story of love & perseverance

In the evenings, we went out on the town and had a good time. The local bands played music, but they weren't very good.

However, there were two girls who could play instruments very well, and often performed in public. They were sisters from Shanghai, and played modern, up-to-date music. We were wowed by them, people came down just to watch them perform.

One of the girls played the Spanish guitar, and I couldn't help but feel attracted to her.

I tried to get close to her, but there were too many other boys. They were better looking than me. Unfortunately, she was interested in another guy at the time.

I was very sad. My friends suggested that I should move on, and I think that's one of the reasons why I went back to Malaysia for a while.

But I also knew that her suitor wasn't compatible. He couldn't speak much English, unlike her. I also knew that he wouldn't be able to join her when she returned to Shanghai. But I was free to go there.

In Shanghai, I became a commercial pilot with the Central Air Transport Corporation. I used my piloting skills to fly rehabilitation and relief flights in postwar China.

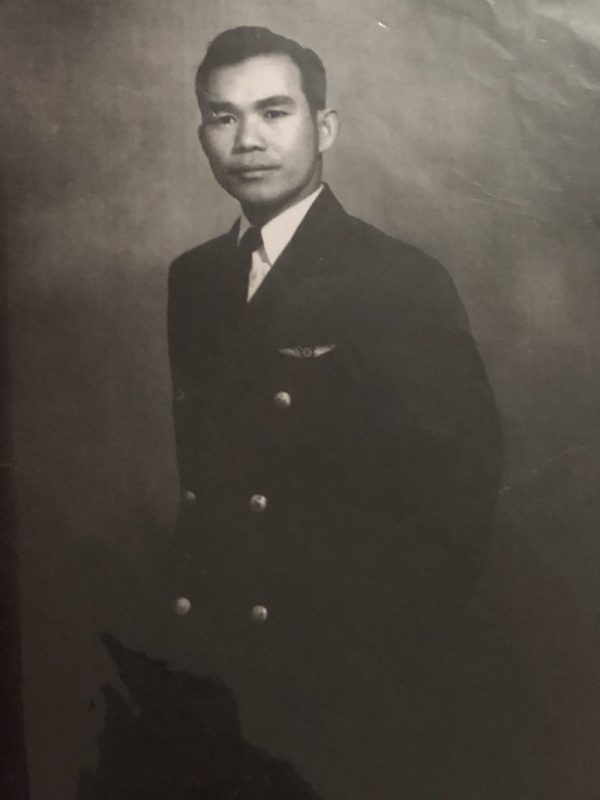

Captain Ho, as a young commercial pilot in postwar Shanghai. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho, as a young commercial pilot in postwar Shanghai. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

"She didn't want to see me at all"

Meanwhile, I started to befriend her parents. They liked me a lot, and knew I was interested in her. I would chat with her mother and played chess with her father. But she didn't want to see me at all.

Their Shanghai house had three storeys. If I was on the ground floor, she would be at the top. If I went up, she would go down to the ground floor. Her parents were embarrassed, but I didn't mind. I was willing to be patient.

Meanwhile, she was communicating with her suitor by writing letters, but his English wasn't very good. Her Chinese wasn't that good either. So they couldn't really communicate.

It took three years. But suddenly, she warmed up and didn't mind going out with me. I didn't ask why, I was just happy. We talked more and became close.

Shanghai was the best years of my life.

Captain Ho and Augusta. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho and Augusta. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Leaving the sinking ship — and a hasty wedding

However, the Communists were still advancing, and I could see that the Kuomintang were losing the war. I couldn't believe it. After World War II ended, the Kuomintang had a large military, an air force, and a legitimate government.

But they kept losing and retreating. I even flew all the way to Manchuria up north, and saw for myself the evacuations of the wounded soldiers and families. My airline was almost like an emergency service.

Back in Shanghai, there was turmoil and uncertainty. People were running away and leaving town. When Beijing fell, it was big news. I flew shuttle missions to Qingdao, dropped food and aid relief three times a day until the city was lost.

The Communists crossed the Yellow River and took Nanjing. I knew that was it. Shanghai would fall soon as well.

It was not safe, there was no security if we remained in Shanghai. I told Augusta we had to leave. So we got engaged, because we didn't know what was going to happen.

I told her to get ready, as I planned to take her away just before Shanghai fell.

Captain Ho and Augusta on their wedding day. On either side of them are Augusta's uncle and aunt. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Captain Ho and Augusta on their wedding day. On either side of them are Augusta's uncle and aunt. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

There was no elaborate wedding dinner once we finally got engaged. She just invited a few of her relatives, and we took a few photos together. She didn't mind, she was aware of the circumstances. We were married on May 5, 1949.

I told her to get ready. I said:

"I'm going to fetch you, there's no time to wait in Shanghai. You must say goodbye to your parents and your folks. I don't know when you can see them again."

It was tough. I felt uneasy about taking her away from her family. But we were married, so I had to look after her.

I came back on May 18. There was a curfew in place, with refugees fighting everywhere. We couldn't stay any longer. The next morning, I flew her down to Hong Kong, and we said goodbye to Shanghai.

An important decision

Thanks to my wartime experience, I could find work as a commercial pilot. Malayan Airways was founded in 1946, and I was interested in working for them.

The question was, Malaysia or Singapore?

Malaysia was a better prospect, from an aviation point of view. It was the larger country, with overseas territories in Borneo. So it had the market for domestic flights.

Singapore didn't have any domestic flights, just international ones. At the time, we also didn't have the aircraft, the operations or the talent.

I came from Malaysia, but at the time I felt that Malaysia was not efficient in running things. I wouldn't say that Singapore was much more advanced, but when it came to running the airlines, it was still somehow able to compete on par with Malaysia despite the gap in their resources.

So I took the plunge and settled in Singapore.

We arrived in Singapore in 1951, and I started work at Malayan Airways as a pilot.

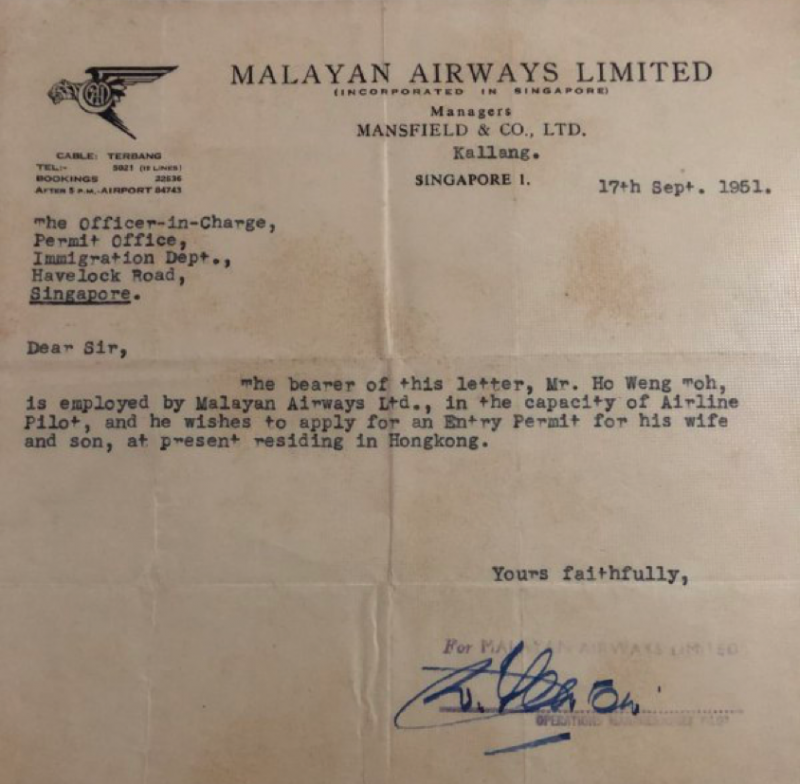

Letter requesting Captain Ho's family to join him in Singapore. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Letter requesting Captain Ho's family to join him in Singapore. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

"We went down... raised our hands, and became Singaporeans"

In 1959, Singapore was about to obtain self-government from the British. At the time, each person in my family had a different passport.

I held a Malaysian passport, while my wife had a Portuguese passport. My son was born in Guangzhou, China, while my daughter was born in Hong Kong. It was very troublesome.

So I thought that this was my chance. We went down to St Joseph's School, raised our hands, and became Singaporeans. Once that was done, we had to think about Singapore's future. Our allegiance would from that day on be to Singapore.

Despite the uncertainties, we hoped for the best.

Reflections on the 1960s

Even while Singapore was under the British, Lee Kuan Yew had his own thinking and his own ambition to run Singapore.

He had a strong team at the time, especially with Goh Keng Swee, but also his other subordinates.

At that time, Tunku Abdul Rahman (Malaysian Prime Minister) and Ismail Abdul Rahman (Minister of External Affairs) had their own thinking of Malaysia. They were very powerful.

Those days were very critical. Both sides were very strong, politically. I remember that Lee was almost arrested and put into jail in Kuala Lumpur.

When Lee announced Singapore's independence on TV, I felt that it was a little bit premature, a little bit unnatural. He was crying, he did not expect it to be like that.

It was almost thrust upon him, to make that decision. It was too big, even for a strong man like him, to make a decision like that.

In those days, the PAP had just started, and we only had the Gurkhas to protect us, but the ministers were very matured. We are doing well today, but back then we didn't know how it would turn out, if we had the capabilities.

Postscript:

Captain Ho and Augusta raised their three children in the newly-independent nation-state of Singapore. He remained with Malayan Airways through the Separation as it became Malaysia-Singapore Airlines, and later continued flying with Singapore Airlines. Captain Ho retired as Chief Pilot in 1980.

Captain Ho's years in the Malaysia-Singapore Airlines are also storied, and we will bring you a third article on his contributions to Singapore Airlines and our aviation sector soon.

Augusta died of lung cancer in 1977, but Captain Ho remains active today, even with the Airline Pilots Association of Singapore, at the age of 98. He lives with his son Fred in Pasir Ris, and enjoys playing Bridge with friends.

On a boat trip, coming back to Singapore, 1950. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

On a boat trip, coming back to Singapore, 1950. Pic courtesy of Captain Ho.

Here's part one of Captain Ho's story:

And here's another story retelling his involvement in Singapore's commercial aviation history:

Top image adapted from pics courtesy of Captain Ho.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.